Finding Your Roots Is Easier Than Ever. But For Some Sarasotans, the Results Weren’t What They Expected

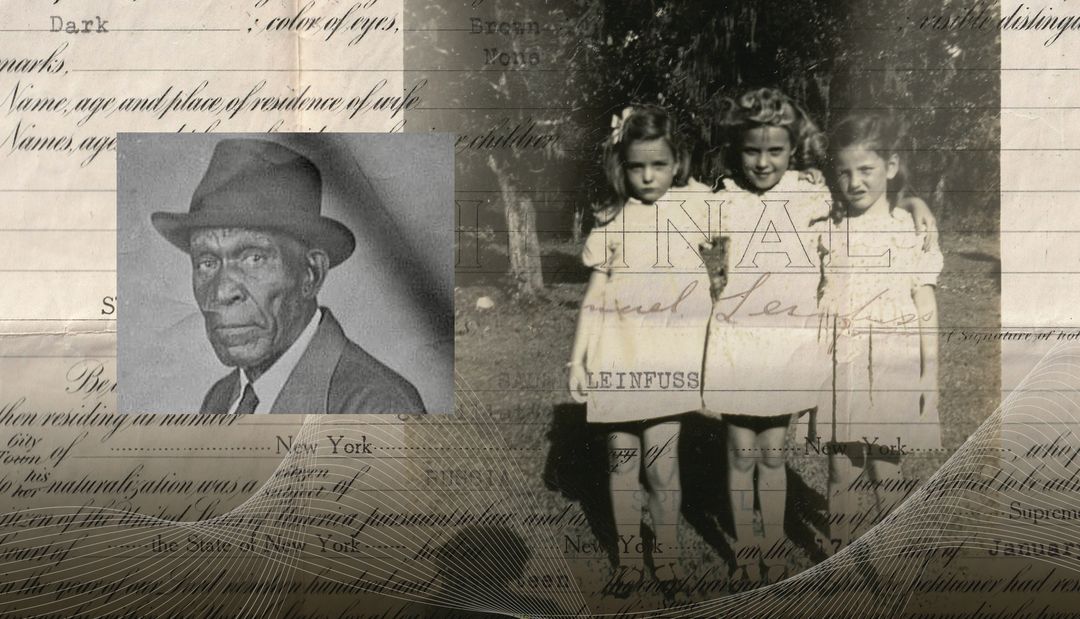

Left: Dara Brooks’ grandfather Monroe Tolbert; right: Vicki Entreken’s mother Geralda Cravey at age 5 (left), with two children who would later become adoptive cousins; background: 1917 citizenship paperwork for Samuel Leinfuss, the author’s grandfather.

Image: Courtesy Photos

I 've held onto a small scrap of paper since 2002, when I’d hastily written down the names of relatives that my father had never bothered to inform me and my sister about. “I didn’t like them,” was his only explanation.

Now, two decades later, I’ve registered for free with FamilySearch, a genealogy database operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints whose origins date back to 1894. I look up my mother’s parents, Harry and Celia Keller, who died when I was two months old in one of the first ever plane bombings (a life insurance suicide). With their records come their daughters’ names: my mother Adele (deceased) and my aunt Dorothy (deceased). “Not true,” I exclaim, having just returned from visiting my 95-year-old aunt Dorothy in a nursing home in Boston. I add a note: “Dorothy is not dead yet!”

I type in the name of my beloved grandfather, Samuel Leinfuss, who died when I was 5 years old. One of my earliest, most vivid memories is of being left behind while my parents attended his funeral. Search results: born in 1892 in Russia; parents: Pincus and Rose Zucker; spouse: Lena; children: Jerome, Paul (my father). All deceased. Then I search for an aunt my father had reluctantly told us about two decades earlier and find an Adam, a Brian and a Meryl, all with the surname of Leinfuss. My father had told us we were the only Leinfusses anywhere. I burst into tears.

I’m far from the only person to shed a tear while learning about my family history.

“I cried,” says Nancy Johnson, the 73-year-old president of the Genealogical Society of Sarasota. “When I found out that my father’s great grandfather burned someone’s barn down in the 1850s and went to federal prison, I sat at the computer and cried, knowing how much the family must have struggled to survive after that.”

There have been many such emotional moments along Johnson’s genealogy adventure, during which she has amassed a file on more than 8,600 people, including an Irish bigamist, a Mayflower Pilgrim and a 50-something illegitimate son of a cousin. Johnson’s interest in family history, perhaps unsurprisingly, runs in the family. In 1906, Baldwin Maull, a relative on her mother’s side, wrote a book tracing the family’s lineage back to the 1700s. With the primary source references that book contains, Johnson was able to follow the Maull line all the way back to William the Conqueror (1066-1087). She even went to the French town of Maule (aka Maull), where she received a medallion based on her ancestors’ ties to the city.

Family memorabilia, along with websites like FamilySearch, Ancestry and Genealogy.com, and companies that offer DNA test results like AncestryDNA and 23andMe, can all give people a springboard into genealogy research. But for a deep dive, researchers must hunt down historical records in the places where their ancestors lived.

“You can’t solely use digital resources, because many of those records are secondary sources,” says Johnson. It is possible to find primary sources like birth certificates and marriage licenses online, but only if the origin city, county or state has done a thorough job of digitizing its records. When she retired, Johnson dove headfirst into a quest to learn more about her father’s family history. “It took a long time, but I finally found what I needed at the Daughters of the American Revolution library in Washington, D.C.,” says Johnson.

Some genealogy seekers have a passion for history ignited early in life. Others experience a triggering incident, such as receiving surprising DNA test results or discovering a relative’s unexplained items or records, which often occurs after the person’s death.

The former is true for Dara Brooks, 66. “I started out being really enthralled in what my paternal grandmother would tell me,” says Brooks, a member of five genealogical societies, including the Genealogical Society of Sarasota, the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society and the National Genealogical Society. “She had a habit, usually when she was rolling dough, of carrying on a conversation—only she was the only one in the room,” says Brooks.

When Brooks was around 6, she asked her grandmother whom she was talking to. “Well, I miss my mama and papa, and I know they can hear me,” was the answer. After that, Brooks kept asking questions. By 13, she had begun using a notebook to capture what was, essentially, her family’s oral history. In her 20s, while traveling for work, she started visiting relatives with two cameras and a camcorder. Later, she produced a family newsletter for more than 15 years.

“Somewhere along the line, I came to believe it was my responsibility to get [our family history] out there,” says Brooks. That family history was part of a larger story of race relations in the United States. Various members of Brooks’ family left Alabama for Northern cities like Chicago, Detroit and Gary, Indiana, during the early half of the 20th century, making them part of the Great Migration that transformed America.

“I’ve changed immensely because of my genealogical journey,” says Brooks. “No research involving African American roots in America is complete without delving into slavery, Jim Crow, redlining and genocide. I have learned some things that keep me up at night.”

Other genealogical researchers have found themselves thrust into the role by surprising DNA test results. In the DNA-reveal memoir Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love, author Dani Shapiro tells how, through a casual decision to take a consumer DNA test, she learned she was not related to the man she thought was her father. In today’s DNA-speak, this is called a non-parental event, or an NPE.

Twenty-four hours after Shapiro discovered that she had been conceived through artificial insemination at a time when the science was very new and shrouded in secrecy, she was able to identify her biological father (the doctor who did the insemination) and was watching a video of him online. The author of four other memoirs and a novel titled Family History, Shapiro found her sense of self upended. “It turns out that it is possible to live an entire life—even an examined life, to the degree that I had relentlessly examined mine—and still not know the truth of oneself,” she wrote.

As a little girl, Kim Sheintal was curious about how she was related to the people around her, but the explanations only confused her. “Two sisters who married two brothers. Cousins married cousins. My mom tried to explain, but I was too young to comprehend what she told me,” says Sheintal, the president and co-founder of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Southwest Florida.

Sheintal built her first family tree in 1982, filling it with about 200 names. In the decades since, she has collected 200,000, and she can tell you details about each discovery. Sheintal has also taken DNA tests. The results of one matched her with a cousin in Australia who had heard family stories similar to those Sheintal had absorbed. Together, they found a mutual connection through the name Lebovitz to the Bilu group, a collection of Jewish people who left Russia for the Middle East in the 1880s. In 2018, Sheintal visited a museum in Israel dedicated to the history of the Bilu movement. While there, a museum employee helped connect her with a Lebovitz descendant living in the area.

Sheintal keeps up with the latest genealogical research strategies through the meetings of the Jewish Genealogical Society. She says that many people who attend the organization’s meetings did not grow up Jewish, but discovered, as adults, that they are biologically Jewish.

At a society meeting held last November, 50-year-old Elisheva Richmond revealed how, when she was 18, her grandmother, who was close to the end of her life, asked for a box of mementos from the family home. Inside, among other telltale items, was a ketubah, a Jewish marriage contract.

“[My grandmother] told my mom that her Catholic marriage was preceded by a very private Jewish wedding held in a basement of a house in Fairhaven, Massachusetts,” Richmond said at the meeting. As Richmond looked back, all the signs were there. “We were an observant Catholic family,” she said, “but every Friday, my grandmother would put two candles on the table, make a funny, braided loaf of bread and have a family dinner.” Eventually, Richmond embraced Judaism and, when her son was 16 years old, the then-single mother moved her family to Israel for 10 years.

Many Jewish people hid their heritage because of antisemitism. This was likely the case for the family of Julian Ortiz, Richmond’s fiancé. The two connected online during the Covid-19 pandemic. Ortiz was raised Catholic in Puerto Rico, but he had recently learned that his DNA was 23 percent Jewish. While Ortiz’s pursuit of DNA testing was motivated by curiosity, an interest in science and a fondness for technology, he says that, through Richmond, he started to learn more about Judaism. That common thread brought them together. They are now living together in Lakewood Ranch.

Vicki Entreken’s moment of surprise came a decade ago, when she was going through the possessions of her newly deceased mother and discovered a box full of letters, strange photos and a notebook. But it wasn’t the mysterious items alone that sent her on a journey to uncover the secrets and learn the truth about her mother’s life. Entreken, now 56, was also deeply troubled by the sense that she wasn’t able to feel sadness or grief about her mother’s death.

As Entreken uncovered her family history over time, it revealed a pattern of devastating generational betrayal and abandonment. “I knew my mother had been abandoned when she was 8 years old and then adopted,” she says. “She worked on a farm. But I didn’t know the extent of the abuse there.”

Entreken became obsessed with trying to understand why her grandmother would abandon her daughter (and a son, as well). “I started researching [my grandmother’s] childhood and discovered that she had been married off just weeks after turning 15,” says Entreken. She realized that her grandmother was essentially also thrown away by her family while she was still a child. When Entreken looked into the lives of previous generations, she found more of the same: a pattern of marrying off daughters when they turned 15.

“My mother’s experience was so traumatic that she vowed to never abandon her own children,” says Entreken. “She broke those chains.” Over time, Entreken realized that, because her mother hadn’t learned anything about the love of a mother or family, she couldn’t pass that on to her own daughter. The insight was healing for Entreken. “Instead of seeing my mother as lazy and uncaring, I now understand what she went through and how little she knew about being a mother,” she says.

Entreken says she could “finally accept that, even though my mother was broken, she did everything she could with what she had. I wouldn’t have understood that without researching her childhood environment and that of her mother.”