New College Alumna Sofia Ali-Khan on Racism and Reconciliation

This article is part of the series Listening to Diverse Voices, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

Sofia Ali-Khan

Image: Moussa Fadel

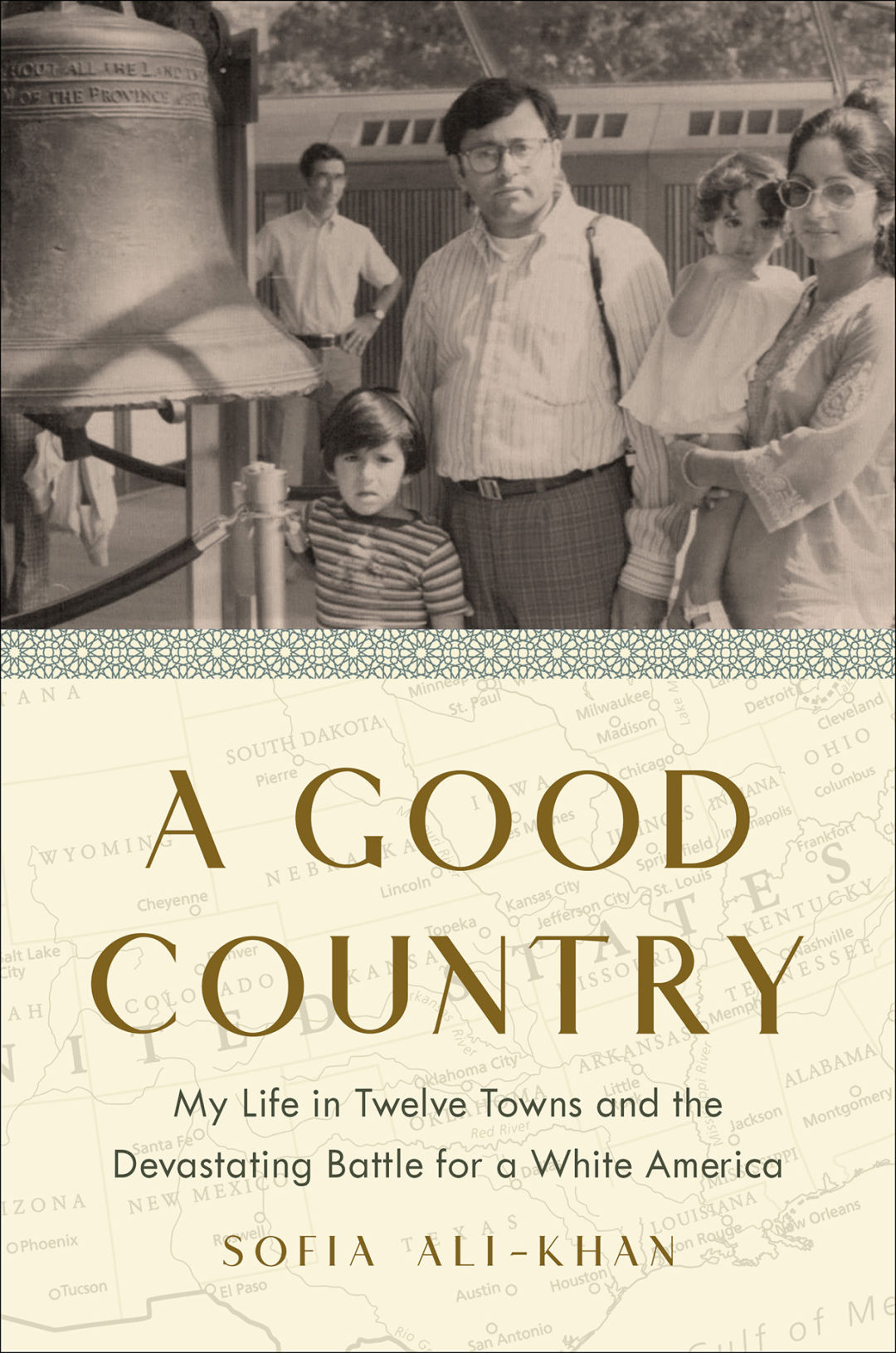

Attorney, activist and New College alum Sofia Ali-Khan’s memoir, A Good Country: My Life in Twelve Towns and the Devastating Battle for a White America, grapples with colonialism and the U.S. legacy of exploitation and racism against Black and Brown people.

Each chapter in the book follows Ali-Khan, now 47 and a mother of two, through a different town, braiding her own story with the history of the color lines in each. Ali-Khan was born in Tampa, Florida, lived in Seminole and grew up in a white suburb near Levittown, Pennsylvania; and spent time in Chicago, Charlottesville, Little Rock and Sarasota, to name a few. Finally, she moved her family to a suburb of Toronto to live the American dream she was denied south of the border.

A Good Country: My Life in Twelve Towns and the Devastating Battle for a White America by Sofia Ali-Khan

Image: Courtesy Photo

Ali-Kahn will speak at New College on Wednesday, Nov. 9, in a talk titled "A Good Country: An Exploration of Memory and History's Role in Justice," alongside local activist Vicki Oldham and New College professor of anthropology Uzi Baram. We spoke with her ahead of her talk to find out more about her book, her work, her thoughts on the current political climate and more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What did racism look like during your four years in Sarasota as a student—and has it changed?

"In the Sarasota chapter of A Good Country, I describe what was probably a similar experience to other students of color at small liberal arts colleges, who frequently don't see themselves reflected in the faculty or curriculum. I've been pleasantly surprised to see a lot of changes at New College in the last 20 years.

"The issue of who shows up in the curriculum is a very live debate in Florida today, where there is legislation that limits history and civics curricula in public schools. I went to elementary and high school in overwhelmingly white suburbs and anticipated college as an opportunity to figure out what was missing from my educational experience. In the book, I describe having close friends who clearly felt a personal connection to the material they were studying and wondered why I couldn't seem to feel that same connection to scholarship. It turns out that when one is able to study the social sciences and humanities with protagonists who looked like one's self and have the same social references, one learns to locate oneself in their society and culture.

"If the characters or the struggles you’re learning about are difficult to relate to one's own life or experiences, it’s harder to understand those things in human terms. The curriculum offered can feel two-dimensional. While I was at New College, I had an opportunity to take just one course with a professor of color, a South Asian visiting professor, who really inspired my interest in political science. When she left, my foothold in that subject—my way in—vanished. I found that in other political science classes, people of color and our interests were rarely, if ever, on the syllabus. When we did show up, it was in a footnote on civil rights or women. I'd show up to class hyper-focused on the footnote and my professors were stymied because most of the readings weren't about the issue I was engaged with. What they didn't get was that I was looking for a doorway into the material.

"Anthropology, similarly, was generally taught as a European study of Brown and Black people, with a lot of exotification. Again, my sense is that things at New College have changed dramatically, but at the time I was a student, bell hooks had written Ain’t I A Woman? just 10 years before, and Kimberlé Crenshaw had just coined the term intersectionality. Those things hadn't filtered down yet. They weren't in the curriculum.

Why do you think racism is pervasive here? Why can’t it be reconciled?

"You can’t reconcile what you don’t see as a problem. When my kids were in pre-school, they learned the four steps of apology: This is what I did wrong; I’m not going to do it again; tell me how I can make it up to you; and I’m sorry.

"There are several steps that need to happen before you get to ‘sorry’ for reconciliation to work. I often get pushback for discussing the history of America's color lines; I frequently get asked what I would say to the argument that these things are the distant past. One of the things I do in A Good Country is link current issues or persistent color lines to the histories I tell.

"Closing the door on the past or minimizing what's happened is not how reconciliation works. There needs to be an acknowledgment of wrongdoing, an affirmation of the humanity of the person wronged, and real reparation of harm. We’ve not yet effectively taken the first step of implementing a public education curriculum that honestly tells the story of our country’s foundation. We don't describe it as a settler colonial project or say that much of our infrastructure, including cleared land and many of our railways, were the work product of enslaved Africans. We’ve never had a national conversation about what reparation for the devastation of Black and Native people would mean.

"Of course, those conversations are happening, they just aren't being widely acknowledged by power brokers. There's a Native-led 'land back,’ movement, and an active conversation about reparations for the descendants of the enslaved. In the few instances in which reparations have been won, they have been terribly inadequate. For example, the Ocite Sakowin, widely known as the Sioux, were pushed out of their vast homeland in the Great Plains. In 1980, the Supreme Court agreed that the Black Hills, a small portion of that land, had been taken from them unlawfully, without compensation, and ordered that the government pay $17.5 million in restitution.

"By contrast, a single gold mining operation in the Black Hills had extracted $18 billion worth of ore over the preceding 126 years. You see the discrepancy. The Ocite Sakowing have refused the money, saying they'd like their land back. If the state offers an apology for wrongdoing without the goal of paying proper reparations, the unspoken imperative of that project is still to hold onto the power and the resources. And that causes ongoing harm, so it's not an effective apology. There is no effective reconciliation because the wrongdoing is right here, in the present."

Over the years, you moved around between North and South within the U.S. Does racism shift much according to geography?

"Racism is pervasive in America, but the way I was racialized in different places, and the ways the color lines operated in different parts of the nation, varied quite a bit. I passed for white at New College, but when I moved to Little Rock after graduation to be a community organizer, white women would walk up to me and touch my hair and ask me, ‘What are you?’

"From 2008 to about 2014, my husband and I lived outside of Chicago where many of the suburbs had been sundown towns for decades—meaning, Black people could expect violence if they found themselves there after sundown. This is how segregation often works in America: people of different races interact during the day, but it's very clear where everyone is expected to return to at night.

"When my husband and I were looking for housing in and around Chicago, we found the color lines very sharp. Often, if you crossed a single street, you could tell you'd crossed into the white area or into the Black area of town. Neither of us really understood that what we saw was rooted in a violent history. In 1901, white residents of Maywood, Melrose Park and Bellwood lined up on train platforms armed with revolvers to keep Black people migrating from the South from settling in those towns. A sociologist named James Loewen found that by 1970, 70 percent of Illinois towns with populations greater than 1,000 people were all white. Chicago itself was a major site of the nationwide violence over segregation during the 'Red Summer' of 1919."

What do you think of the recent state-wide legislation affecting public Sarasota schools?

"I think they're a reflection of a broader American fear that reparations are overdue. They are the next chapter of the ongoing racist battle to keep public schools segregated. We never won that battle, I don't think. Although our schools are desegregated by law, they remain widely segregated in practice for a variety of reasons. The new battleground is, who is valuable enough to have a place in the curriculum and the culture of our schools?"

What do you make of Gov. Ron DeSantis flying undocumented families to Martha's Vineyard?

"This was clearly a sort of political prank, a way of saying that northerners don't understand the issues at the southern border. People seem to be debating that, and talking about whether state dollars were wasted, but what I see as the issue is the willingness of the governor of the state to publicly and unapologetically deny the humanity of those people—to be able to treat those people like pawns, to put them through all of that, and still be considered a viable candidate for the 2024 presidential primary.

"As Americans, we used to expect self-control and decorum on both sides of the aisle. When we went into Iraq, even then-President Bush was careful to say that Muslims weren’t the enemy. There was an understanding after the civil rights era that prevented American political leaders, mostly, from being overtly racist. But DeSantis seems to be following Trump's lead in reversing that. It tells us a lot about where we are as a nation."

What might you say to those who think racism is all in the past?

"Of course, many of our nation's most egregious wrongs are technically in the past. Our country was very literally built upon them. It's also true that time only moves in one direction, so we have to move forward. The question is, are we trying to correct the wrongs of the past in order to secure a viable future?

"Canada is not utopian, but some interesting things are happening here that Americans ought to consider. The federal government has officially taken the position that it has to 'decolonize,' and that the genocide and subjugation of First Nations people is not consistent with modern human rights values and so can no longer be the premise of the state of Canada going forward. As a result, the level of animosity and hostility towards First Nations people in Canadian politics is substantially less than it is in the United States. There is a large and growing public platform for First Nations, Inuit and Metis perspectives and priorities here. The increasingly mainstream talk about whether there is an impending civil war that you find in the U.S. media isn't happening here.

"How we deal with the past is shaping the present in very clear ways. It defines our political priorities and agendas in both Canada and in the U.S., but it's very clear that the way the U.S. is dealing with, or rather failing to acknowledge, past wrongs and take reparative action is creating incredible pressure and volatility. American exceptionalism really stands in the way of American voters looking around at other similarly situated countries to see what they're missing out on.

"For example, in New Zealand, the state has proclaimed itself bi-cultural, reshaping itself to represent Māori interests, as well as those of the mostly European, non-Indigenous population. They have begun to imagine what comes after colonialism by instituting policies of power-sharing and cultural equity. In Ontario's third-grade curriculum, non-Indigenous children learn that they’re settlers and discuss what that means. My kids both went through that curriculum and it wasn't demeaning or upsetting for them. It was presented as a description of the world around them, and the beginning of a conversation about how we take responsibility and do the right thing. In Canada, there’s also the practice of land acknowledgment. At government and public events or before school and sports events, there’s typically an acknowledgment of whose traditional or unceded territory we're on.

"When we say that out loud, we remind ourselves of a colonial past that is not yet repaired. It’s a bookmark that says, ‘We have this work to do.'

"You can be an ‘80s kid in suburban Pennsylvania and never once interact with Native people. There’s a dark drive in our curriculum and our culture to make Native people past tense. That erasure is the end-game of cultural genocide, and it serves a political interest in maintaining a colonial project. So those things make a real difference."

Do you still have family in the U.S.? Do you miss being in the U.S.?

"I still have family here. I miss it. My children miss it. It’s hard to not miss a place where you were born and grew up and got married. But when we think about coming back, we reckon with the data on mental health outcomes for Muslim-American children. Studies show that in the last 20 years, health and wellness outcomes have tanked for American Muslims.

"As an example, more than half of Muslim parents reported that at least one of their kids have been bullied at a public school in the previous year. In a third of the cases, the bully was a teacher or administrator at their school. As a parent, I had to ask: what am I setting my kids up for? When I was growing up in southeastern Pennsylvania, people just didn’t know what a Muslim or Pakistani was. But now there's open hostility towards Muslims.

"Moving, financially and logistically, is not for everyone. But there were a lot of factors in deciding whether we would take on that hardship. We understood it as the price we were paying to live in a society with dramatically less anti-Muslim sentiment and dramatically less gun violence. Kids don’t do lockdown, active-shooter drills in public schools here. That is one thing I find unfathomable about where America is right now, and it's why I think American exceptionalism does us no favors: If we continue to insist that America is the best place in the world, we tend not to realize there are other places we can learn from. It traps us in the reality we’re in."

What history have many Sarasota locals missed out on?

"The Sarasota chapter of A Good Country discusses the Seminole Wars, which were Andrew Jackson’s campaign to eliminate both the Seminole people and Maroons—formerly enslaved people who had escaped to carve out new lives—from Florida. Together, these individuals and groups had built a complex and free society across lines of race, culture and language. It sounds a lot like the American Dream. But it was seen as a threat by early America, which understood itself as an exclusively white society with an enslaved Black underclass and Indigenous peoples to be exterminated or exiled.

"During my talk at New College, I’ll also touch on the origins of the Ringling family’s wealth. The Ringling mansions are a big part of New College's campus and culture. But we don’t really examine the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus as a Jim Crow-era institution, and how the exploitation and trafficking of Brown and Black entertainers contributed to Ringling's wealth. The Ringlings were able to build mansions in Sarasota with minimal infrastructure. We don’t think about who was just barely eating to generate that wealth. The story of the exploitation of Black labor shows up in the histories of many other American universities. In one example from 1838, Jesuits at Georgetown University sold more than 272 enslaved people to save themselves from financial ruin."

What can we do to help?

"Several friends who had never previously considered running have successfully run for local public office. Having a variety of people in local leadership roles is changing how things are done and changing the conversations we're having in our communities. We all have to start where we are, in Canada or in the U.S. We can all think about who runs our town and pick out one issue that really bothers us—like why our mosque can’t get built or why the line between my school district and another one is a color line. We can all pick one battle and show up at those meetings.

"It also helps to build relationships, so that you're talking to people about what's happening in your community. That could be a book club or talking to your neighbors. Even talking to our own kids about the things missing in their curriculum is essential."

Hear Sofia Ali-Khan speak at the Sainer Pavilion at New College, 5313 Bayshore Road, Wednesday, Nov. 9, from 7 to 8 p.m. RSVP to the free event here. Follow her on Twitter @sofia_alikhan.