The Unsettling World of Circus Freakshows Once Flourished in Sarasota

Sideshow freaks have all but disappeared from American life. The spectacle of exhibiting human beings with unusual disabilities seems repellent, and for good reason. People with disabilities are now symbols of courage and achievement over great odds.

One hundred years ago, things were much different. A child born with an abnormality or strange condition was an object of shame and embarrassment. Most were hidden away or placed in asylums. Though it sounds impossible to believe today, many American cities had so-called “ugly laws”—ordinances that prohibited anyone “in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object, from being in public view.”

Chicago’s ugly laws weren’t repealed until 1973. There was one curious exception to the ordinance. Such people could be exhibited commercially, “for the purposes of entertainment or eliciting disgust.” And it was in this unsettling bit of reasoning that the sideshow comes in.

It was often an individual with severe disabilities’ only chance at… I was about to say normal life, but a normal life was an impossibility, given the social mores of the day. But at least here was an opportunity for them to control their own destiny, find employment and belong to a community.

And many did. Southwest Florida became a haven for them. The circus and sideshow industries were headquartered here, in Sarasota, Tampa and Gibsonton. But who were these people who were once our neighbors? What sorts of lives did they live? Many adapted to their unusual situation. They built careers, they married and raised families, prospered financially—and then retired to pleasant homes and cultivated their rose gardens. Others became bitter and angry and drank themselves to death. They were, in the final analysis, just people.

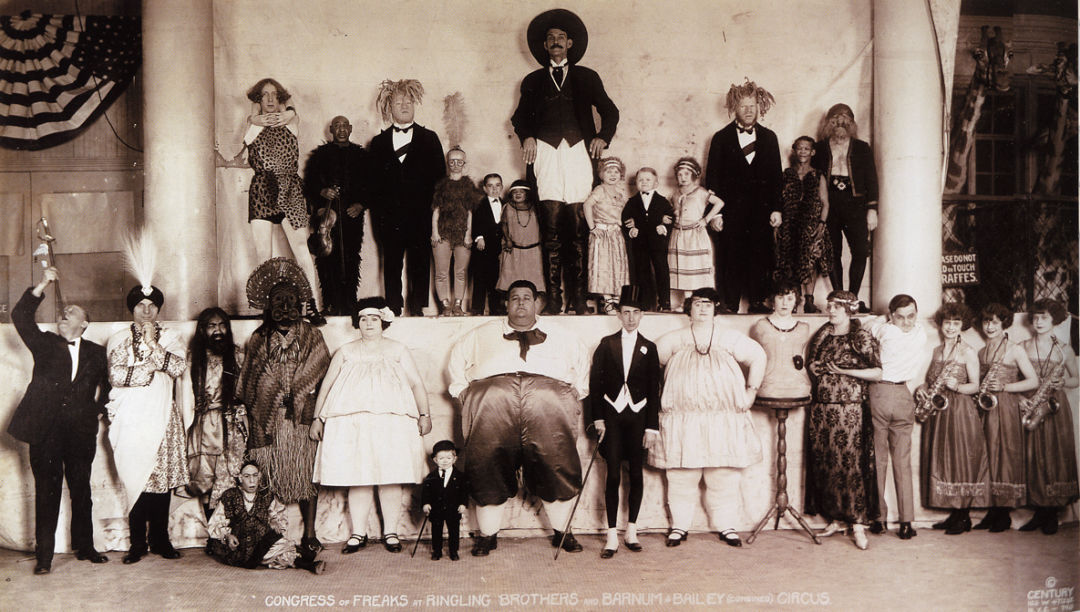

The "Congress of Freaks" at Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus

Image: Courtesy Photo

Sideshows were an important part of American show business in the period between world wars. There was no Internet, no television, no iPhones, and the population was much more rural, poorer and less educated. The circuses and carnivals that crisscrossed the country provided wonders that the average person had never experienced and could scarcely imagine. Exotic animals, death-defying thrill acts, clowns and showgirls—and off to the side, in an area of its own, was the sideshow.

Inside the Big Top, things were bright and glittering and happy. At the sideshow, a different feeling took over. Here things became grotesque and dangerous. A man swallowed swords. A woman handled snakes. There were rigged games of chance at every turn. Pickpockets plied their trade, and tucked away was the cooch show, where women danced and a flash of nudity was promised—and often delivered. Sideshows were wicked places and routinely denounced by the town’s ministers and women’s clubs.

The most notorious attraction was the freaks. “Nature’s Oddities,” they were billed, and every sideshow had them. They were usually presented in a “10 in one”—a long narrow tent with 10 separate attractions. On the “bally”—the outdoor stage at the entrance—a man called the “talker” enticed the crowd with what is called a ballyhoo, a noisy spiel about the curiosities inside. One or two acts might be beside him to give the crowd a preview—a female snake handler complete with snake, a fire-eater or sword swallower, perhaps a tattooed lady (one of the most famous, Artoria Gibbons, worked until she was in her 80s) or the fat lady or man.

Virtually every sideshow used little people in some way. They were considered cute, non-threatening crowd pleasers. Most were not distinctive enough—or short enough—to be featured as a separate attraction, and thus became part of a “midget show” in which they sang, danced and told the corniest of jokes. “How did you get so tall?” “I ate what was right. How did you get so short?” “I ate what was left.” The Chicago World’s Fair in 1933 had a sideshow called “Midget City” with 125 performers, all people of small stature.

Perhaps the most famous little person act was Sarasota’s own Doll Family, who lived in a house on a quiet street just south of Bee Ridge. German born, the Dolls were four siblings with dwarfism. The quartet—Frieda (who changed her name to Grace), Daisy, Kurt (who changed his name to Harry) and Hilda—moved to America and took on their agent’s surname Earle. They carved out a legendary career for themselves. They worked constantly in a wide variety of venues and also had an impressive movie career. Not only were they featured as Munchkins in The Wizard of Oz, but they also appeared with Laurel and Hardy and Lon Chaney, and Harry Doll played the male lead in the classic film Freaks (more about that later).

Giants were also a big draw. Two of the most famous lived in nearby Gibsonton, a town 49 miles north of Sarasota. Johann Petersen was 8 feet and 9 and a half inches high. He was born in Iceland and often billed as the “Viking Giant.” In Europe, he toured with an act in which he and several little people played the marimba. After immigrating to the U.S. after World War II, he transitioned to sideshows and had a long and profitable career, then retired to Gibsonton, where he often appeared at a local flea market, a stooped but still imposing figure in an enormous chair, selling his famous rings. They were so big you could fit a 50-cent piece through them. He was noted for his charitable work with the Showmen’s Association, playing Santa Claus for underprivileged children. They have a replica of his size 23 boot displayed in a local park.

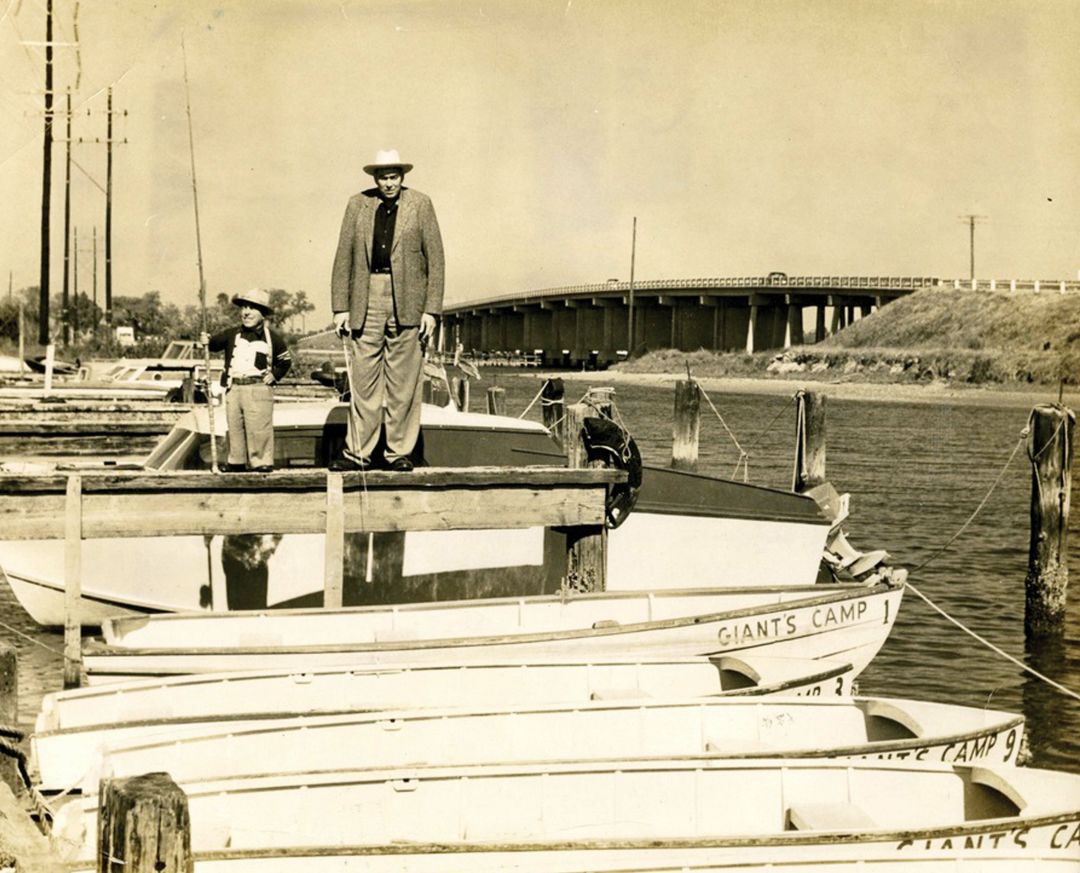

Little person Casper Balsam and giant Al Tomaini turned Gibsonton into the winter quarters of the sideshow.

Another prominent Gibsonton giant was Al Tomaini, who measured in at 8 feet and 4 and a half inches. His wife, Jeanie, appeared to have no body from the waist down. They billed themselves as The World’s Oddest Couple. Entrepreneurially inclined, the Tomainis owned several sideshows themselves and built a fish camp and restaurant on the Alafia River where it enters Tampa Bay. They are credited with turning Gibsonton into the winter quarters of the sideshow trade. Al also served as Gibsonton’s fire chief. Colonel Casper Balsam, a dwarf, was the town cop.

Conjoined twins were also a premium sideshow attraction, and any couple who gave birth to a pair were soon approached by sideshow managers who wanted their children—dead or alive. (Malformed fetuses preserved in formaldehyde were also an important part of the sideshow, though most were rubber fakes.) The most famous conjoined twins were “Siamese twins” Chang and Eng Bunker, who became major celebrities in the 19th century. They are even mentioned in Moby-Dick. They made a fortune touring and then settled on a plantation in North Carolina, where they owned slaves, married a pair of sisters and fathered 21 children. During the Civil War, their condition was much written about, providing, as it did, a human metaphor for what the country was going through. Among their thousands of descendants is great-great-granddaughter Alex Sink, who ran for governor of Florida against Rick Scott.

The most successful conjoined twins of the 20th century were probably Daisy and Violet Hilton, whose life story inspired the Broadway musical Sideshow. Born to a barmaid in England, they were “sold” to a couple who saw the money that could be made. Here were conjoined twins who were pretty young girls, and they were joined back-to-back, which made them seem less “freakish.” The mercenary couple drilled the twins in singing and playing musical instruments, and by the time the sisters were old enough to perform they had an act. Their long career including playing themselves in a movie titled Chained for Life. They also retired to Gibsonton, where they operated a fruit stand.

Single freaks ran the gamut of unusual medical conditions that rendered them, in the popular mind of the day, ugly to an extreme degree. Their stage names paint a vivid picture: The Living Skeleton, The Spotted Boy, The “What Is It?”, Sealo the Seal Boy, The Sheepheaded Girl, The Man With Two Faces, The Mule Faced Woman, The World’s Ugliest Woman, Percilla the Monkey Girl.

The question still hangs in the air. Were they doing it under duress? Was it a form of slavery? Were they being held in some sort of bondage by unscrupulous managers who became the legal guardians of some of their performers?

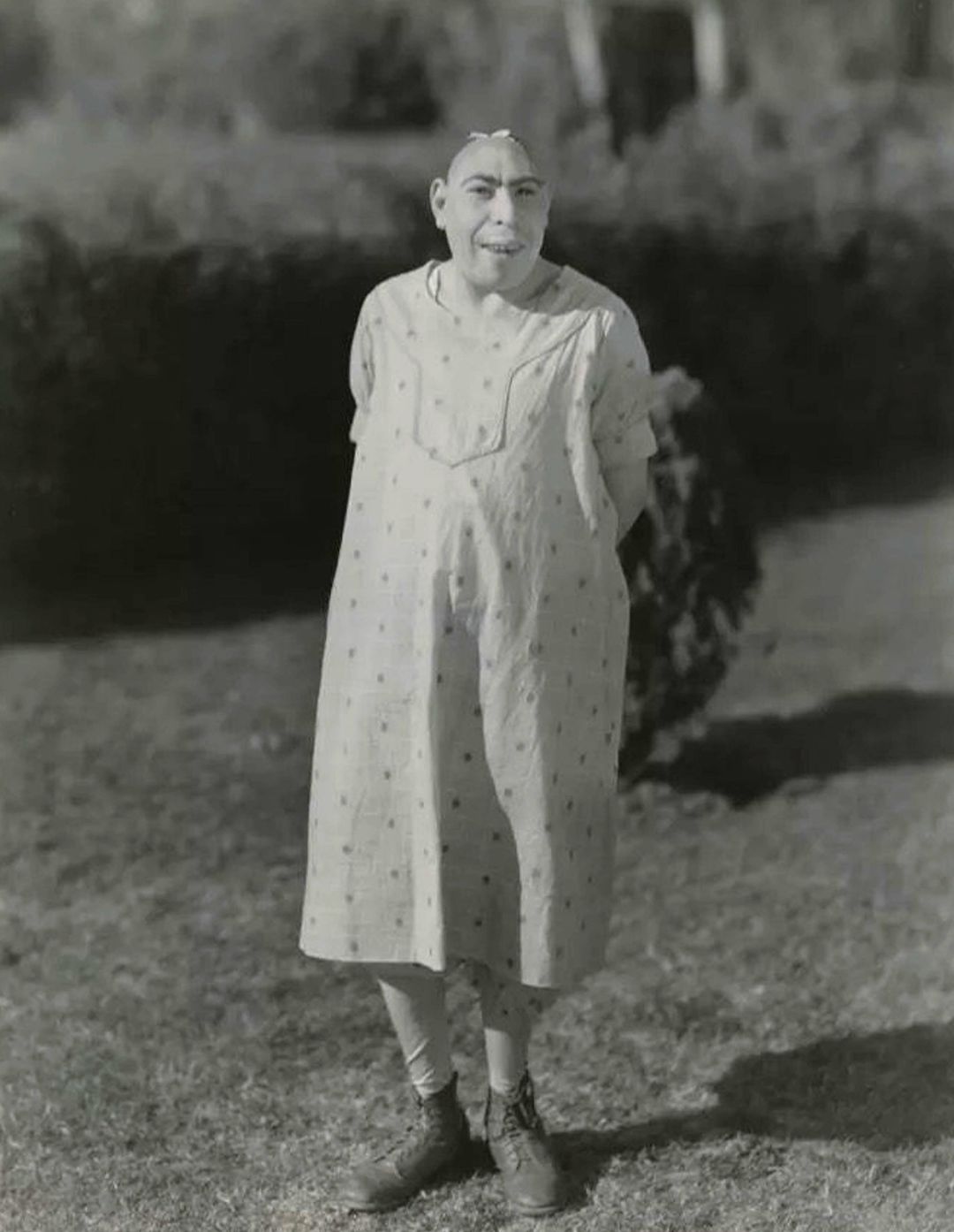

Schlitzie was a famous American sideshow performer who appeared in the 1932 movie Freaks and lived into her 80s. Fans still visit her grave.

Image: Public Domain

The best answer is, sometimes, but not as much as you might think. And this brings up the heartbreaking—or heartwarming—case of Schlitzie the Pinhead, arguably the most iconic freak of all. He was born with a condition called microcephaly, which causes the skull to slant back from the eyes. Schlitzie was always presented as a female so the diapers he had to wear could be hidden under a dress. Everyone referred to him as “she.”

Schlitzie had a mental age of two or three. Her conversation was mostly just repeating things she heard, but this gave her a childlike quality that was instantly appealing. You got the feeling that here was a happy person, delighting in the world around her.

Born to a family in New Mexico, Schlitzie was hidden away in shame until a sideshow impresario obtained custody. She had a full-time nurse to take care of her and soon became a headliner in the business. Her career spanned more than 50 years, and she traveled all over the world. Eventually her guardian employer died, and she was put in an asylum. Someone who knew her from her working days discovered her there, obtained custody, and she went back to work. She lived into her 80s and is now buried in a cemetery in Los Angeles, where fans still leave flowers on her grave.

Schlitzie’s case is worthy of close study by a college class in ethics. I can almost see the essay question on the final exam: “Was Schlitzie being exploited? Of course. But did that very exploitation give her a better life than she would have had in a mental hospital? Discuss.”

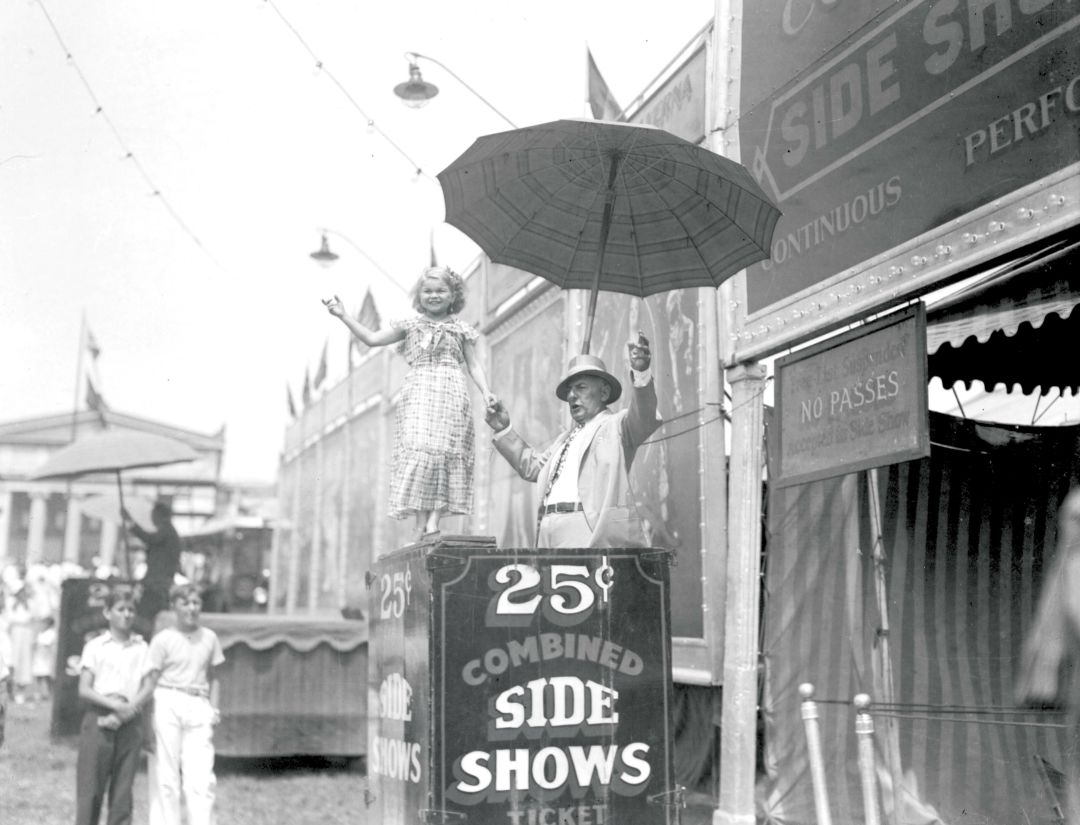

Sarasota’s Daisy Doll with sideshow manager Clyde Ingalls in front of the bally stage.

Image: WHS-Circus World Museum

Not all freaks were bona fide freaks. The sideshow business thrived on deception and lies. More facial hair was added to the bearded lady. The fat man’s weight was exaggerated by 100 pounds. The three-legged man had a prothesis cleverly attached. Many acts offered a substantial reward to anyone who could prove they were a fraud. This itself was usually an admission that they were indeed.

The half man-half woman, known as the half-and-half, was invariably a female impersonator. There were even a few male impersonators, but real hermaphrodites were rarely part of the sideshow world. Gay people certainly were, however. Some managers considered it bad luck not to have at least one gay person in the show, and one troupe was known to be predominantly gay.

A sideshow was hard work, particularly for those with mobility problems. Fifteen shows a day was not uncommon, and living accommodations were usually a house trailer or even just a cot in a freight car, with meals cooked on a hot plate. But the financial rewards could be excellent. Some top acts made as much as $3,000 a week, and this was during the Depression. Additional sums were made through the sale of photos, miniature Bibles and other souvenirs and knickknacks. These were promoted during the performance, sometimes quite aggressively. Percilla the Monkey Girl was famous for threatening hell and damnation for those who didn’t buy her picture.

The classic motion picture Freaks (1932) offers a look at life backstage in a sideshow. It stars many of the people we have been talking about, including Schlitzie, the Hilton sisters and three of the four members of the Doll family. It was given a full-scale production (by MGM, no less), but the picture was controversial from the start and banned in many places.

It presents the performers as a group of misfits and outcasts who have created their own world. They come across as fully rounded human beings, caught in a situation not of their own making and trying to make the best of it. They love, hate, help each other and betray each other. Some, like Schlitzie, are eternal innocents. The freaks in Freaks are the heroes. They are the ones we root for, and we develop a true affection for the cast. The villains are the “normal” people, particularly the most beautiful ones. Critic Andrew Sarris called Freaks “one of the most compassionate films ever made.”

The most famous scene in the film is a party put on to celebrate the engagement of Harry Doll to a beautiful, fully formed aerialist. She is after his inheritance. The freaks welcome her with a dinner, proclaiming her an honorary freak. They pass around a loving cup full of wine, chanting, “We accept her, we accept her. One of us, one of us. Gooble goble, gooble goble.” The experience so unnerves her that she shows her true colors and her plan collapses.

To get a more recent account of working with sideshow performers, I contacted movie director Brian De Palma, who used several for a nightmare sequence in one of his early films, Sisters. De Palma reports that he hired the performers through an agent and that they flew up from Florida to New York, where he booked them rooms at the Hotel Pennsylvania.

How did they function with the other actors? “Margot [Kidder] and Jennifer [Salt], the stars of the film, were pretty freaked out, which worked out well for the nightmare dream sequence we were filming,” he says. “But the freaks were very professional and easy to work with.” The one he remembers the best was Eddie the Giant. “He tried to do his best in overcoming his many difficult physical limitations,” De Palma remembers.

His overall impression? “They were very sweet and gentle people.”

After a successful career lasting decades, conjoined twins Daisy and Violet Hilton operated a fruit stand in Gibsonton.

There are still plenty of traveling carnivals that play fairs and such, but they no longer feature sideshow attractions. It’s all rides and food wagons and games where you win a big stuffed animal.

The industry is still based in Gibsonton, however, and a drive around town will reveal many of these rides waiting for the next job. But you won’t see any freaks. They have died off, leaving a legacy that we still have trouble dealing with.

The big turning point in public opinion came after World War II. Many servicemen were returning missing arms and legs, and it was unpatriotic to treat them with disrespect. As depicted in the 1946 movie The Best Years of Our Lives, their friends and relatives readjusted their thinking, overcame any squeamishness and the veterans became a loved and valued part of the American family.

The war changed things in an even bigger way. Back in the 1920s and ’30s, the eugenics movement was in full force. It advocated eliminating undesirable genetic traits through forced sterilization and sequestering the “unfit and the useless.” The idea was supported by a surprising number of important people, including Theodore Roosevelt, W.E.B. Du Bois, Herbert Hoover and even Helen Keller.

But as the war ended and the depth of the Nazi atrocities was shown to the world, the eugenics movement collapsed. The concentration camps demonstrated the logical conclusion of that so-called science—mass extermination of “undesirables,” indeed of whole races. It shocked the world into a new era of human rights.

Today, people with disabilities have been mainstreamed into society. The Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990 guaranteed them services, employment, accommodations, transportation and education. The country’s attitude toward the disabled is one of the few triumphs of political correctness. “They” are now “us.”

And good riddance to the sideshow—sort of. I highly recommend you visit the Showmen’s Museum in Gibsonton for a fascinating look at this lost subculture. It was a community of outsiders, wicked, exploitative, deceitful, vulgar, tasteless. But also rather grand in the total lack of shame. There was no low it wouldn’t stoop to, no tragedy it wouldn’t exploit, no lie it wouldn’t tell.

The Doll siblings with Ringling Brothers clown Lou Jacobs and an unidentified woman.

My favorite sideshow story:

One manager had suddenly lost his half-and-half. The poor man had been arrested doing something indecent down at the bus station, and the manager needed a fill-in, quick. He located an older, long-retired half-and-half and wired him bus fare. As soon as he arrived, the man was thrust into a tattered gown and, lacking a wig, they borrowed one from the Wild Man of Borneo. It still had twigs in it.

The manager began his spiel with the poor guy standing next to him on the bally looking ancient and disheveled. This was what was called a sex act, in that sex—of a strange and bizarre kind—was what they were selling. The problem with a sex act is that the performer must be sexy in some way, and this man was not.

The manager felt the audience turning. They weren’t buying it. He wasn’t selling any tickets. So, in a moment of pure sideshow genius, he changed his tack and declared, “It may be difficult for you to believe what I have told you about this person to be true. I know it is so because this is… my mother.”

The ticket line immediately formed at the left.