Wild Gulf Shrimp Are the World’s Best, But the Future May Be in Aquaculture

Yes, the beaches are beautiful, and so is the weather most of the time, but Spanish moss and wild Gulf shrimp were my two main motivations when I decided to buy an apartment in Sarasota four years ago. Eccentric? Maybe, but also discerning, because if the pale green tassels of lichen fluttering from certain trees always tantalizingly tease some deep ancestral memories just beyond my reach of recall, the succulent sweet saline taste of the shrimp works like some sort of maritime communion wafer linking me to the Gulf of Mexico, that vast body of water that is America’s Mediterranean Sea.

In other words, fresh wild Gulf of Mexico shrimp are a gastronomic luxury food I’d place right up there with truffles and caviar, the difference being that they’re much more affordable. And if you live in or visit Sarasota, you can eat your fill of these crustaceans all year round, since they’re sold by quality fish mongers like Maggie’s Seafood, which sets up at numerous farmers markets around the region, and are featured in many local restaurants, such as Sandbar on Anna Maria Island, Michael’s on East, Star Fish Co. in Cortez and Château 13 in Bradenton, all of which give a precise callout to the Gulf shrimp they serve on their menus.

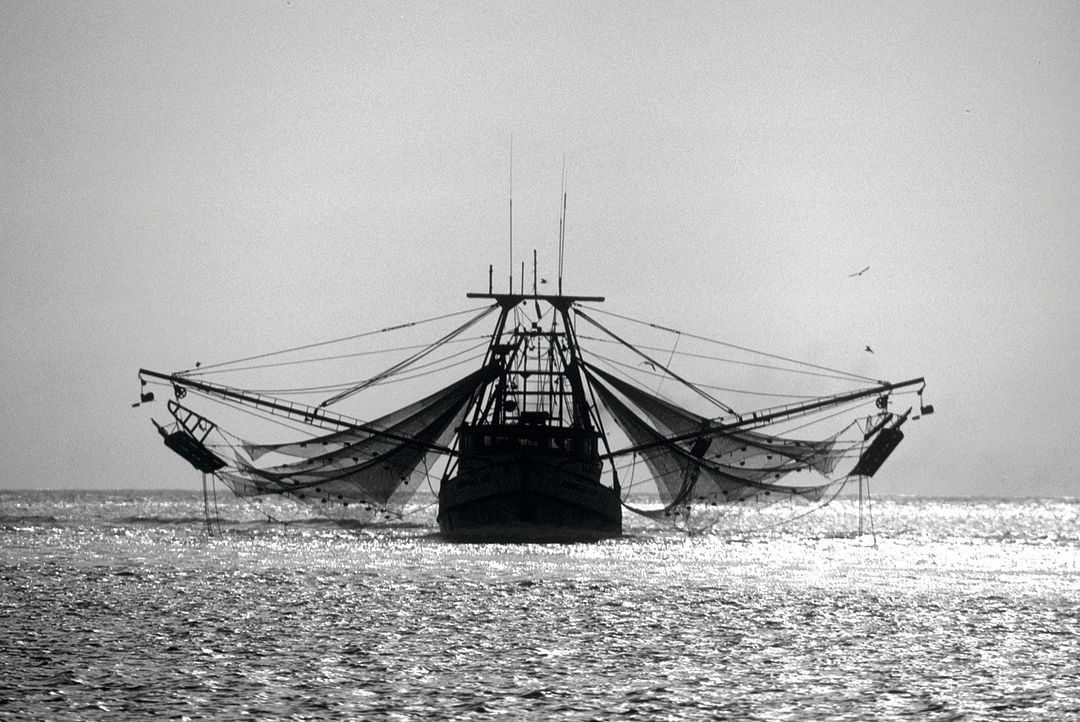

A Gulf shrimp boat

This pleasure is, of course, due to the seeming munificence of the Gulf of Mexico, which is America’s defining body of water, because the 600,000 square miles of water are so rich in historic, gastronomic, commercial and cultural associations that are profoundly American. This is why it constantly surprises me how much we take the Gulf for granted.

For my part, I now see that I was guided back to the shores of the Gulf by hereditary cravings I didn’t completely understand until they were finally satisfied again.

I grew up in New England, the chilly right thumb of the United States, but my father’s family originally settled in New Orleans in the 1780s. This was when a certain Jacinto, aka Hyacinthe Lobrano, arrived in the Gulf of Mexico from Italy and became a respected “lieutenant,” according to his obituary in the New Orleans Picayune, to Frenchman Jean Lafitte, the most famous pirate plying and plundering the waters of the vast, flat, shallow sea.

After America won the Battle of 1812 thanks to help from Lafitte and his band, the fearsome corsair married a French woman from a notable family and had a passel of sons, whose descendants fanned out along the Gulf Coast and up into the Mississippi River Valley. One of the pirate’s grandsons, Gustave Stubbs Lobrano, my New Orleans-born paternal grandfather, eventually went north to attend Cornell University and later worked as the fiction editor of The New Yorker. I never knew him, because he died young, but my father always talked about how the first thing they did on any trip back to Louisiana to see family was gorge themselves on just-landed shrimp.

“The best shrimp in the world come from the Gulf of Mexico,” my father often remarked when we’d eat them at home. My mother bought them frozen, since they weren’t sold fresh in our Connecticut suburb, or in a restaurant in New York City.

By the time I moved to New York to work as a book editor in the 1980s, Gulf shrimp had become scarce and expensive at the same time that Americans were eating more shrimp than ever before, and all-you-can-eat shrimp became a major marketing motor in the restaurant industry.

As the James Beard Award-winning chef Andrea Russing of the Lantern restaurant in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, observes, “If you have food you need to move, the fastest way to do so is put a shrimp on it.” Out of the 15 pounds of seafood consumed per capita in the United States each year, four to five pounds are shrimp. Americans, including me, quite simply have an insatiable appetite for shrimp.

But as I inadvertently learned on a trip to Thailand 25 years ago, there is wild shrimp and then there is farmed shrimp.

On a muggy morning, we left Bangkok for the seaside town of Hua Hin with a driver, and about an hour later we entered one of the saddest, strangest and ugliest landscapes I’d ever seen: miles of empty, white-rimmed bunker-like paddies gouged into the land. Our driver didn’t speak English, so there was no way of asking him about the origins of this hideously ravaged landscape. When we stopped to buy water at a roadside shop, I realized it was also some sort of agricultural supply store and started reading the labels on the big sacks of foul-smelling fish meal and plastic buckets of powdered weed killer and antibiotics they sold. Eventually, it was a little diagram with English instructions on one of the bags that made me realize we were driving through acres and acres of abandoned ponds where shrimp had once been raised.

“Aquaculture in Southeast Asia is like the Wild West,” explained the Australian expat manager of the hotel where we stayed that night. “There’s a huge amount of money to be made farming shrimp, because the demand for cheap seafood is insatiable, but eventually the ponds become too toxic to use for a new crop due to pollutants, including the heavy metals in fish meal used to feed the shrimp, and the antibiotics put in the water to control diseases. So it’s cheaper to abandon a pond and build a new one than it is to clean them up. One way or another, I wouldn’t eat farmed Asian shrimp at gunpoint.” That’s an opinion seconded by many chefs and prominent food writers when I recently asked about this product.

Paul Greenberg, author of American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood and four other books on American fisheries, explains the environmental damage that shrimp farming is causing in countries like India, Bangladesh, Ecuador and elsewhere. “Coastal mangrove forests are four times more powerful in terms of sequestering carbon dioxide than tropical rainforests,” he says. “We’re digging up our best carbon sinks to grow more shrimp.”

In a recent podcast with Greenberg, Thomas Hymel of Louisiana State University’s Sea Grant and the Louisiana Direct Seafood program said that shrimp fishing in the Gulf first came under pressure in the 1980s after cheap imported farmed shrimp started claiming market share from the wild catch brought in mostly by fishermen working out of Florida, Louisiana and Texas ports. The commercial pressure was exacerbated by declining American catches caused by urbanization and rising sea levels.

“Shrimp spawn in full-strength seawater offshore,” Hymel explained. “Then they hatch and the baby shrimp migrate to brackish areas along the coast, which is where they grow. These coastal wetlands are like pastures, and when they’re destroyed, shrimp catches fall.”

The Southern Shrimp Alliance, an organization of shrimp fishermen and processors in the eight warm-water shrimp-producing states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Texas, says the landings of shrimp in the Gulf of Mexico in 2021 “have been 23 percent below the prior 19-year historical average of 24.9 million pounds.”

The Shrimp Alliance website also features news like the recent crackdown by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on antibiotic-contaminated shrimp from Bangladesh, and other industry issues. “One of the other serious problems of farmed shrimp is that you don’t know who’s working on those farms or how they’re being paid,” says Greenberg. “There’s a lot of forced and child labor on these farms.”

Key West pink shrimp

Aware of all these problems, many Sarasota chefs specifically feature wild locally landed shrimp on their menus, despite the fact that it’s more expensive than the farm-raised shrimp used by the food-service industry. “You have to explain to the customer why it’s worth spending the extra money to eat wild seafood. I tell them it’s a question of both good taste and good health, and I tell them to ask questions,” the late Sarasota chef Arthur Lopes, of Pomona and Lila, once told me. SeafoodWatch.org, which is run by the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, is an excellent source of regularly updated information on the sustainability of current catches of wild and farmed seafood.

Most of the wild shrimp for sale and on menus in Sarasota comes from shrimp boats working out of Cortez, which is a half-hour drive north at the head of Sarasota Bay.

Founded by several families from Beaufort, North Carolina, in 1890, Cortez became one of the largest and busiest fishing ports on the Gulf Coast of Florida by World War II, with its catches of fish and shrimp peaking in the mid-1960s.

Today, only a handful of boats still regularly fish for shrimp out of this port, which has suffered considerably due to competition from imported shrimp and declining shrimp stocks in the Gulf of Mexico. Florida commercial fishermen are subject to a complex regulatory system. In state waters, commercial fishing is regulated by the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission. Fisheries in federal waters off the coast of Florida are managed by regional councils. According to the Gulf Fisheries Management Council, which oversees the federal waters off the central coast of West Florida, there are no limits on catches of brown, white and pink shrimp in federal waters, while the catch for royal red shrimp is limited to 337,000 pounds each year.

Chef Steve Phelps of Indigenous has found another solution to the shrimp quandary. “I think fish farming is the future,” Phelps said during a recent interview on CBS This Morning. “This is because of pollution and fish quotas,” he added, saying he also wants his guests to be able to make choices that are good for the planet. When it comes to shrimp, Phelps serves Sun Shrimp, which are raised by the largest all-natural, sustainable and fresh shrimp growing company in the United States, on Pine Island just north of Sanibel Island and off the coast near Fort Myers.

Shrimp boats in the Florida Keys

Unlike the ghoulish shrimp farms I saw many years ago in Thailand, Sun Shrimp’s 100-acre facility produces preservative-, chemical- and antibiotic-free shrimp. The process avoids the catastrophically wasteful bycatch of less responsible shrimp fishermen (bycatch is the term for fish and other sea creatures, like turtles, that are caught accidentally, but which have no commercial value and are thus thrown away), overfishing, reef damage and air and water pollution.

Requesting anonymity, another Sarasota chef who uses Sun Shrimp instead of wild ones commented, “If you look at the states that surround the Gulf of Mexico, most of them have not been good stewards of the Gulf because their state environmental regulations are so lax. With the pollution caused by the gas and oil industry, agricultural runoff and sewage, I feel more confident about serving scrupulously raised farmed American shrimp than I do wild ones.”

Sun Shrimp certainly are delicate and delicious, and this excellent Florida product makes me cautiously optimistic about the future of aquaculture. (In addition to finding them at restaurants, you can buy them from Maggie’s or order them directly at sunshrimp.com.)

But as long as fishermen are still landing wild shrimp from the Gulf in Cortez, the meal I dream about between visits to Sarasota from my home in France is a plate of sautéed or blackened shrimp with hush puppies, coleslaw, cheese grits and a cold beer at a picnic table at Star Fish Co. For some reason or another, I’m pretty sure my pirate great-great-great-grandfather from New Orleans would have loved this meal, too.

Alexander Lobrano is an award-winning food and travel writer who lives between France and Sarasota. His latest book is My Place at the Table: A Recipe for a Delicious Life in Paris, a gastronomic coming of age story about how a shy kid from Connecticut became a famous food writer in France.