This Sarasota Man Has Traveled the World Hunting Exotic, Dangerous Snakes

Dennis Cathcart at Tropiflora.

Image: Hannah Phillips

“I was born interested in snakes.”

That’s what Dennis Cathcart, 74, told me when I asked him why he made a career out of hunting for snakes. He says he's always been fascinated by the slithering creatures, especially the venomous ones.

At 18, Cathcart graduated high school and began taking trips to the Bahamas and Mexico to realize his dreams. While his peers went to college or joined the more traditional workforce, Cathcart got a job working for wild animal importers in south Florida, and eventually began field studies in Central America for scientists in Miami. All the while, he also kept a "regular" job at a lumber yard in Port Everglades. While he didn't have a formal education in snake hunting, he made a fortune over his peers and learned from mentors like Army Major Herschel H. Flowers in Costa Rica.

Cathcart holding an anaconda.

Image: Courtesy Photo

“I once found a snake on the Caicos Islands that scientists had been unable to locate since the 1930s,” says Cathcart. “They sent me out in hopes I’d find one. I ended up finding two.”

Since his debut expedition, Cathcart has traveled to virtually every country in the western hemisphere. He’s made several trips to the Caribbean, Central America and South America, where some of the world’s largest and rarest snakes are found. In 1968, he began working for a United States Army lab in Costa Rica, where he’d bring snakes for venom processing—a technique that helped create the first anti-venom serum. Until 1976, Cathcart traversed dusty deserts, damp rainforest floors and jungles teeming with exotic life, all in pursuit of the most unusual and dangerous snakes.

People gather as Cathcart examines snakes in Limbe, Haiti, 1968.

Image: denniscathcart.com

“It’s been an exciting and terrific career,” says Cathcart. “I’ve traveled to places where few people have gone, collecting snakes and plants, and have had many dangerous experiences, from meeting tribes of people who don’t want you there to cars and planes breaking down in the jungle to breaking my neck on the Amazon River one time. But I love what I do.”

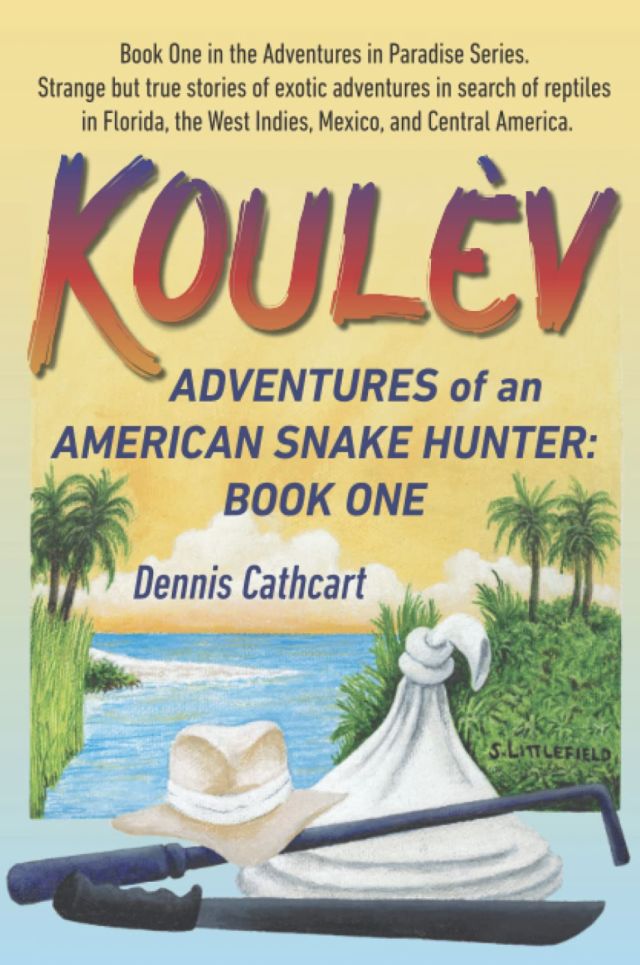

Cathcart also loves writing about his adventures. The first volume of his new memoir, Koulèv: Adventures of an American Snake Hunter, details his exciting travels, as well as his transition into collecting exotic plants, which occurred when he opened his Sarasota nursery, Tropiflora, in 1976. (A second volume is slated to be published later this year.)

Cathcart's first book.

Image: denniscathcart.com

Book One begins in the 1960s in Haiti, a place Cathcart describes as “wild and woolly with lots of snakes and lizards.” He recalls one of his most fascinating captures—a Haitian boa. It was a rare, non-venomous snake that happened to be piebald, meaning it was partly albino. Cathcart says that, given its rarity, if a fellow explorer had caught and sold it, it would have been worth $1,000—and much more today.

The careful art of catching a snake is also detailed in his book. In the Caribbean, Cathcart preferred to catch non-venomous snakes with his bare hands. He’d stow them in sacks of unbleached cotton enforced with double seams and a flap on the top so snakes couldn’t escape or bite.

Since those days, snake hunting technology has been upgraded. Now, there are aluminum clamp sticks—devices that pin down snakes' heads without harming them. That is essential if the hunter aims to extract venom. Another tool, called an “L stick,” has a hook that looks like a question mark at the top. Before these, Cathcart made his own hooks out of golf club shafts and welded heads.

“All these tools are used in an effort to not get bitten,” says Cathcart. “But it still happens. I’ve been bitten by almost every creature there is. It’s just part of the job.”

Cathcart has been bitten thousands of times by non-venomous snakes. Since these snakes typically have small teeth and measure less than six feet, Cathcart claims you hardly feel the bite. Rather, it’s the psychological fear of getting bitten by a snake that overtakes you. Despite this, he never wore gloves or long sleeves and recalls his fellow explorers going bare as well.

When it came to handling a poisonous snake, however, extreme precaution was taken.

“I’ve handled tens of thousands of venomous snakes from working in the lab,” says Cathcart. “We use gloves, long sleeves, forceps to feed them and all other sorts of tools to protect ourselves.”

One day in 1973, Cathcart wasn’t so careful. He was in a rush while feeding a venomous snake and was bitten on his index finger. He was using a pair of forceps to feed the snake a mouse, and the snake’s heat sensor, which is used to hunt prey, picked up on Cathcart's finger, too. He spent eight days recovering at Sarasota Memorial Hospital and was so knowledgeable about the snake’s venom that he advised the nursing staff on how to treat him.

After that bite, Cathcart decided that searching for exotic plants might be a safer bet. His plant expeditions have led him to Thailand, Mo'orea, the Philippines, New Zealand, Indonesia and Madagascar, among other places. Cathcart and his wife, Linda, also traveled to Ecuador several time to collect orchids and bromeliads for Marie Selby Botanical Gardens' collection, and they even supplied 360,000 bromeliads to Singapore's Gardens by the Bay.

Tropiflora.

Image: Hannah Phillips

“Collecting and lecturing about plants has carried us around the world several times over,” says Cathcart. “It’s also kept Tropiflora—six acres of greenhouse, six acres of indoor space and remaining outdoor land—in business. Now, my kids run the nursery.”

Cathcart says the process of writing his first book rekindled his interest in reptiles, which led him to travel to Cuba in April to photograph more snakes, lizards and plants.

Cathcart and his wife Linda in Tasmania, 2015.

Image: denniscathcart.com

Tropiflora often hosts festivals that draw crowds of plant enthusiasts, but, no matter how successful the business has become, Cathcart still considers himself a snake guy at heart. He already has another expedition planned for July 2023.