How Sarasota Shaped the Life and Career of 'Macho Man' Randy Savage

“From Sarasota, Florida...weighing 245 pounds...it’s ‘Macho Man’ Randy Savage!”

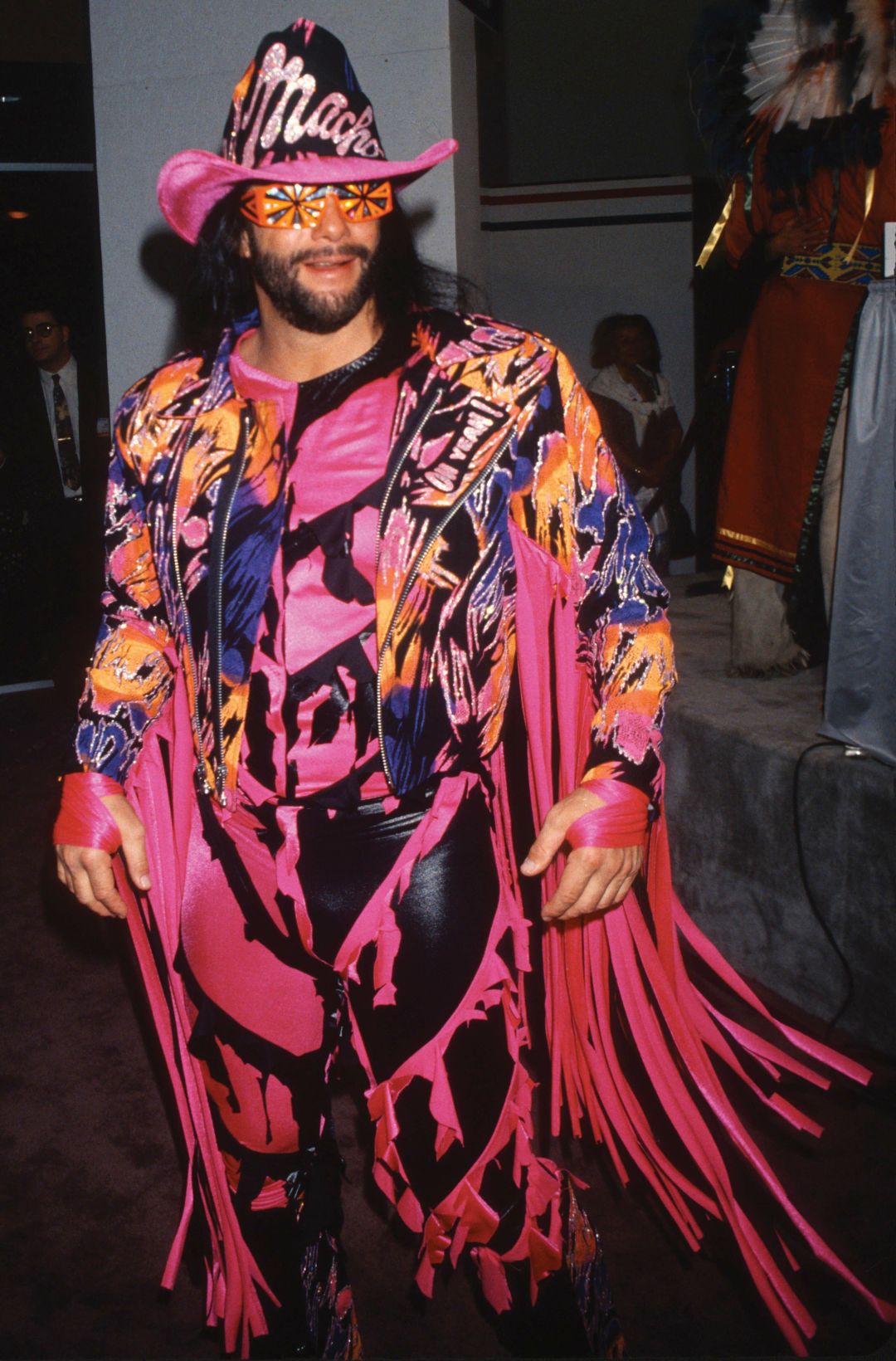

For nearly two decades, that’s how audiences the world over were introduced to professional wrestler Randy Savage. He would saunter toward the ring to the sounds of Edward Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance,” wearing his signature brightly colored accessories: a cowboy hat, sunglasses and a bandanna. For much of his career, his first wife, Liz Hulette—known by her ring name, “Miss Elizabeth”—escorted him. Standing outside the ring, Hulette played the demure, graceful Southern belle, while inside it, the rugged, muscular Savage put on furious, physical, high-flying performances that were among the most highly regarded in the wrestling business. His raspy voice and the intense interviews he gave before and after his matches topped off his unique presentation.

Savage parlayed his skills into one of the most successful and lucrative careers in wrestling history. He held the World Wrestling Federation and World Championship Wrestling championship belts on six occasions, headlined some of the most-watched events of any sport—not just wrestling—and in 2015 was inducted into the World Wrestling Entertainment Hall of Fame. (The World Wrestling Federation became World Wrestling Entertainment in 2002.)

He was equally famous outside the ring, and became one of the best-known pitchmen of the 1990s. You likely remember him imploring people to “snap into a Slim Jim,” shouting, “Oh yeah!” or thrilling moviegoers as the villainous Bone Saw McGraw in the first Spider-Man movie with Tobey Maguire. For a time in the late 20th century, there was no more famous Sarasotan than Randy Savage.

Savage spent only a portion of his life in Sarasota, but his time in the city served as the bookends of his adulthood. In the early 1970s, he lived in Sarasota full time—chasing his dream of becoming a professional baseball player as a member of a St. Louis Cardinals minor league team. While walking

along Lido Beach one day, he met Lynn Payne, a student at what was then called the Ringling School of Art. After several years together, they broke up in the mid-1970s when Savage left town to pursue his professional wrestling career. Decades later, the couple reunited and were married in 2010 on the same stretch of Lido where they met 40 years earlier. Barely a year afterward, Savage died with Payne by his side. He was 58 years old.

One of the first people to note the connection between Savage and Sarasota was Tim Leone, a sportswriter for the Sarasota Herald-Tribune who joined the paper in 1985. Leone recognized the growing mainstream profile of professional wrestling, which had previously been considered a peripheral sport, and became

one of the earliest reporters to profile a professional wrestler in a conventional newspaper.

“I watched wrestling, and Savage was introduced as being from Sarasota, so I thought it was a natural local hook,” Leone says. “He seemed liked a very reasonable guy. He liked talking about baseball.”

Buddy Rogers, Lanny Poffo, Randy Savage and Angelo Poffo on Lido Beach.

Image: Courtesy Rip Rogers

Savage’s path to Sarasota began with his father, Angelo Poffo. The son of Italian immigrants, the elder Poffo settled in Downers Grove, Illinois, outside Chicago.

Angelo served in the Navy during World War II, where he distinguished himself with his athletic prowess. He set a world record on the deck of a Navy ship by doing 6,033 consecutive sit-ups over the course of several hours. After the war, he attended Chicago’s DePaul University and played baseball. While a student, he

met Judy Sverdlin, who grew up in a Lithuanian-Jewish family in Naperville, Illinois, before attending the American College of Physical Education, which

later became part of DePaul. The couple married in 1949 and settled down back in

Downers Grove, where Angelo became a high school physical education teacher. On weekends, he worked as a professional wrestler.

The Poffos had two sons—Randy, born in 1952, and Lanny, born in 1954. Both were highly intelligent. They played chess, like their father, and were inducted into the Downers Grove High School chapter of the National Honor Society. The family was extremely close-knit. Angelo and Judy emphasized hard work and frugality with money, traits that both boys displayed during their adulthoods. The brothers were also very athletic, but their personalities were like night and day.

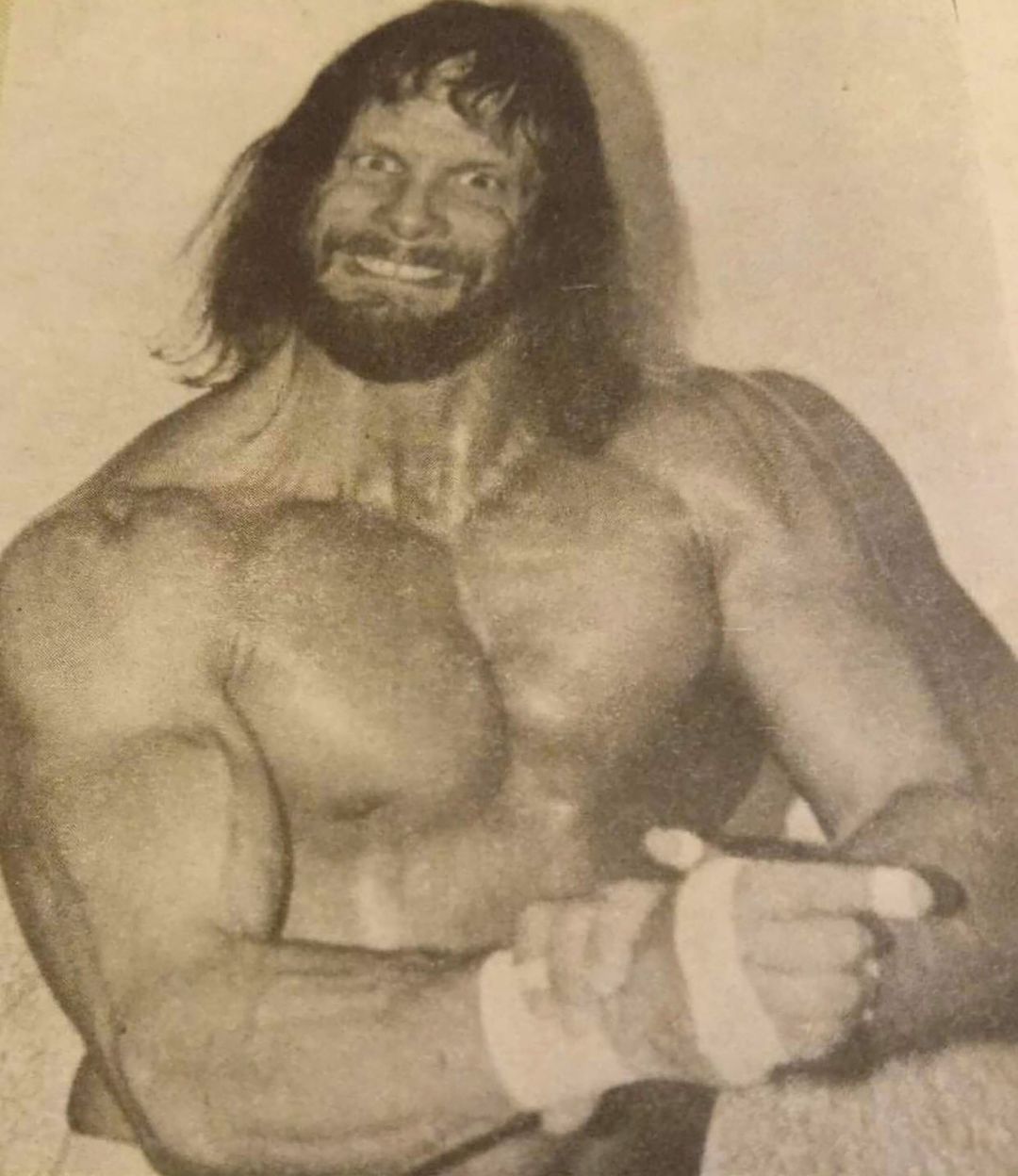

“Randy and Lanny were about as opposite as it could get, but if something went on, they were there for each other,” says Rip Rogers, one of Savage’s best friends. The two shared an apartment and spent endless hours on the road together working for International Championship Wrestling, which was founded by Randy’s father Angelo.

Savage was a star on the Downers Grove High baseball team, batting better than .500 his senior year and earning All-State honors. Nevertheless, he went unselected in the 1971 Major League Baseball draft. But Savage wouldn’t give up,

and his father brought him to a St. Louis Cardinals open tryout, where he impressed the coaches enough to earn a minor league deal. The Cardinals assigned him to their minor league affiliate in Sarasota, the Gulf Coast League

Cardinals, as a switch-hitting catcher and outfielder.

Teammates regarded Savage as quiet, tough and intense. While scouts thought his potential with the bat and glove was limited, Savage put in Herculean efforts. Twice he earned bids to the Gulf Coast League All-Star Game as a catcher and twice he led his team in home runs. Slowly but surely, Savage made a name for himself in the Cardinals organization.

“Randy got the nickname ‘Macho Man’ in Sarasota,” Rogers says. “Whenever there was a fight, he was the first one out there punching somebody.” After a home plate collision with an opposing catcher during which Savage tore several muscles in his shoulder and ruined his right throwing arm, the Cardinals thought his career was over. But Savage showed up at spring training in 1974 ready to play a new position—first base, which was typically the domain of left-handed players.

“The Cardinals thought that was the last they’d seen of Randy,” Rogers says. “Then he shows up after the winter. They told him, ‘We wanted a left-handed first baseman.’ He said, ‘I’m left-handed now. I threw the ball against the wall 1,500 times a day.’ He’d spent every free moment that winter in Sarasota throwing left-handed.”

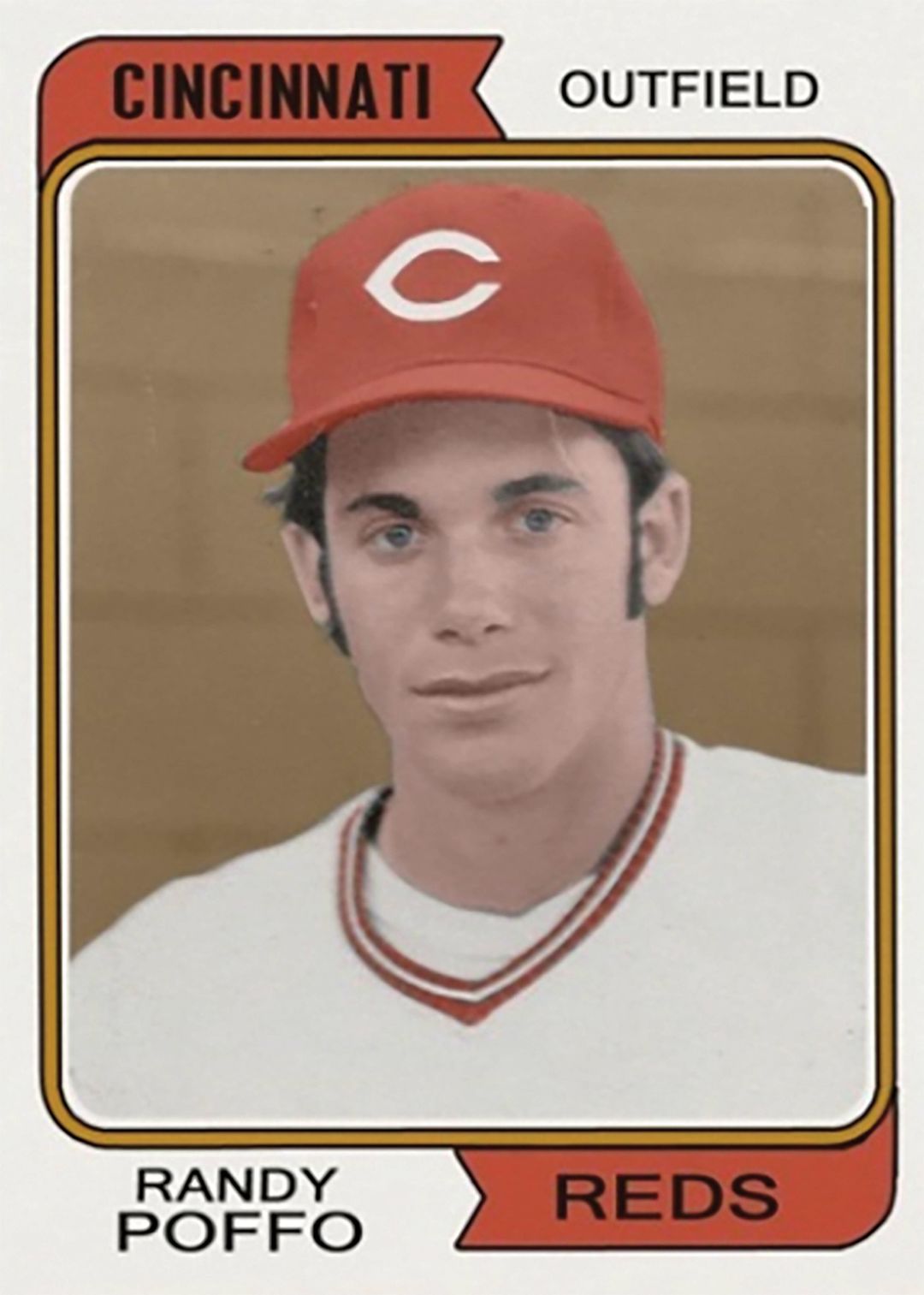

Savage's baseball card from his time with the Cinncinati Reds.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Savage never earned more than $500 a month during his time playing ball with the Cardinals. He lived in a series of cheap motels along U.S. 41, leading a Spartan existence while perfecting his craft. Despite his effort, the Cardinals refused to give Savage another shot. However, the Cincinnati Reds signed him and sent him to their minor league team in Tampa. Savage, though, had trouble making the throw from first base to second, and the Reds cut him after the 1974 season. The White Sox gave him a tryout in 1975, but soon released him, too. By that time, Savage’s father Angelo and brother Lanny had taken to the road full time with International Championship Wrestling, or ICW, and Savage decided to join them. He rarely spoke about baseball afterward. “If Randy brought up baseball, it would be OK,” says Rogers, “but if you brought it up, he’d get a little tense.” Before leaving baseball behind for good, Savage smashed all of his bats, equipment and trophies against a tree.

Savage with his first wife, Liz Hulette, a.k.a. "Miss Elizabeth," in the 1990s.

Image: Adam Scull/Photolink.net

Taking to the road as a wrestler also brought about a painful change in Savage’s personal life. For several years, he’d been dating Payne, the Ringling student he met while walking on Lido Beach, but the pair decided to go their separate ways. Savage was off to Lexington, Kentucky, where his family had set up ICW’s headquarters. Payne moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee, got married and started a family, and the two ultimately lost touch. At the time, ICW was in a pitched battle with well-established wrestling promotions in the Midwest and South. It often ran two shows each night and

worked seven nights a week.

That reflected the Poffos’ business philosophy. They presented a hard-nosed wrestling product that was long on physicality and realism, but short on showmanship. Eventually, ICW worked its way into 11 television markets while building up a network of regular towns to perform in that were in proximity to its base in Lexington.

Rogers became one of ICW’s mainstays. He spent much of the late 1970s and early 1980s on the road with Savage, whom he credits with teaching him the wrestling business.

“When you’re on the road, you do the same thing every day,” Rogers says. “We’ve got to eat right. We’ve got to go to the gym. We’ve got to get on the road and get to the town. Do extra training in the dressing room if you can. You get in, you get out, you don’t get hurt. And we wrestled seven days a week.”

ICW was a genuine mom-and-pop operation. In addition to managing the business, Angelo and his sons wrestled, and Savage’s mother Judy served as secretary and took money at the door during events. While working at ICW, Savage met Liz Hulette, who went on to become host of the ICW television show.

In 1984, Savage and Hulette married. Not long afterward, ICW went out of business, but Savage’s skills as a wrestler and his on-screen presence earned him a shot with Vince McMahon’s World Wrestling Federation, or WWF, the country’s top wrestling promotion company. Savage’s star rose alongside the likes of Hulk Hogan and Andre the Giant as the WWF built a global prominence that was unprecedented in the wrestling business. Hulette served as Savage’s valet, and soon “Macho Man” Randy Savage and “Miss Elizabeth” became the most popular couple in the wrestling business.

Their relationship became frequent fodder for wrestling storylines, as various opponents tried—or were suspected by Savage of trying—to woo Miss Elizabeth away from him. A feud over Miss Elizabeth involving Hulk Hogan served as the main storyline for 1989’s Wrestle-Mania V, one of the best-drawing pay-per-view events in wrestling history. Even after Savage and Hulette’s 1992 divorce, Hulette remained strongly tied to Savage in terms of storyline, continuing to serve as his valet for a time in World Championship Wrestling, or WCW.

Savage climbs to the top of the turnbuckle to do his signature move, the flying elbow.

Savage’s performances were a kind of violent beauty, full of showmanship and high-flying athleticism. Before entering the ring, he often worked out, in meticulous detail, the contours of the match with his opponent. Despite rising to fame in an age of over-the-top wrestling hoopla, Savage made sure that his matches were true simulated fights. His signature move was the flying elbow drop, emulated by millions of fans in backyards and living rooms across America. He climbed to the top turnbuckle, raised his arms over his head and dove elbow-first onto his dazed opponent.

Significant to Savage’s success was his look—namely, the garish outfits he wore in the ring, which became synonymous with the glitz and flashiness of 1980s pop culture. Savage made a strong impression on Michael Braun, the man who designed his outfits during his years with the WWF and WCW. Braun worked for decades in a six-car garage behind his home in South Tampa, designing clothing for rock luminaries like Jimi Hendrix, The Allman Brothers Band and Chicago.

“We made clothes for Hulk Hogan when he was a bass player in a local band called Ruckus,” Braun says. As Hogan gained fame as a professional wrestler, he hired Braun to make his ring attire. It was Hogan who encouraged Savage to give Braun a try.

“Randy comes into my shop and says, ‘The Hulkster said you can make me some clothes,’” Braun says. Initially, Braun made Savage five outfits. They were an immediate hit, adding a sense of spectacle that matched Savage’s in-ring dynamism and acumen on the microphone. Braun, for his part, went on to make clothing for roughly 20 WWF and WCW superstars, including Dusty Rhodes, the Big Show and Brutus “The Barber” Beefcake.

Savage's handmade wrestling attire added a sense of spectacle to his in-ring dynamism.

Savage visited Braun’s shop once every three weeks, often with his parents and his brother Lanny, who also made a name for himself in the WWF as “The Genius” and, like his brother, wore outfits designed by Braun. Savage was always kind and friendly with Braun’s staff—happy to pose for pictures and sign autographs.

One year, he gave Braun autographed Macho Man T-shirts to hand out to garbage collectors on Christmas. Despite his reputation for thrift, Savage took his craft seriously and was willing to spend accordingly on his attire. “He paid for all of these clothes out of his own money, and I made him 45 outfits a year at $800 to $2,500 dollars an outfit,” Braun says. After Savage’s retirement, Braun saw the wrestler far less frequently, but recalls running into him at restaurants like Bern’s Steak House in Tampa, where Savage would happily interrupt his meal to take pictures and sign autographs.

Savage strikes a pose during his International Championship Wrestling years.

Image: Courtesy Rip Rogers

By the early 2000s, Savage’s in-ring career was winding down. He settled in the Tampa area, near where his parents and brother had relocated. He lived for a time in a condo in Treasure Island but soon tired of the constant attention he received in the high-profile spot. He purchased a home near his parents in Largo and kept a close watch over them. He took them to their medical appointments, brought them out to breakfast, bought his father a Cadillac and paid for them to vacation all over the world.

He also became preoccupied with personal security. He erected a high fence around his home, kept guard dogs and installed a high-end security system.

“Randy was always paranoid about people robbing him,” Rogers says. “If he heard a noise, he was up with a gun out ready to shoot somebody. When we ate at a restaurant, he would always have his back to the wall so that he could see everyone who came to sucker-punch him.”

Savage endured a lot of physical pain after he retired. Many of his ailments came from his time in the ring, but also from a neck injury sustained on the set of Spider-Man. Nevertheless, he remained dedicated to his workout regimen. Between sets at the Gold’s Gym in Pinellas Park, he befriended Bo Vespi, then a Pinellas Park police officer and assistant football coach at Admiral Farragut Academy in St. Petersburg. Not long after meeting Savage, Vespi asked if he would speak at a graduation for the area’s anti-drug D.A.R.E. program. Savage was filming Spider-Man at the time and unable to attend, but he persuaded Hulk Hogan to go instead.

“If he saw me in the gym, he knew my wife and kids were likely in the child care area and he would always go say hi to them,” says Vespi, who’s now a deputy sheriff in Palm Beach County and a commander in the U.S. Coast Guard Reserve. “My older boys can remember him stopping and giving them an ‘Oh, yeah!’ He was personable yet reserved. He didn’t let too many people in his circle, but he absolutely loved his family. He admired his father, adored his mother and was very proud of Lanny. He would always say how smart Lanny was.”

Vespi visited Savage several times at his Treasure Island condo and says that the former WWF champion was fun to hang out with, but he spent much of his time fulfilling his personal and charitable commitments. During Savage’s wrestling career, he’d distinguished himself with the extensive philanthropic work he did on behalf of children. Though he never had kids of his own, he was committed to bringing joy and comfort to those who needed it. When Vespi told Savage about the poor condition of Admiral Farragut Academy’s weight room, Savage came by for a visit.

“Randy made time to stop by and speak with the football team and give them all some inspiring words, and we looked at the gym,” Vespi says. “That was when he envisioned us dedicating the gym in his father’s name.”

Savage financed a new weight room at the school on the condition that it was named after his father, who was a Navy veteran like David Farragut, the school’s namesake. Savage’s entire family came for the dedication. A photo of Angelo Poffo breaking the world record for sit-ups now hangs in the weight room.

Savage performs "'Twas the Night Before Christmas" with the Florida Orchestra for the Steinbrenner Family Foundation.

Image: Zuma Press

Savage's philanthropic efforts were generally focused on the Tampa Bay and Sarasota regions. At Christmastime, he played Santa Claus at charitable functions for St. Pete’s All Children’s Hospital and Sarasota Memorial Hospital. He visited children at both facilities throughout the year, losing hundreds of arm-wrestling matches to kids receiving care. For more than 10 years, he brought his Santa routine to Christmas parties for underprivileged children in Tampa and St. Petersburg that were hosted by the Steinbrenner family, the owners of the New York Yankees. (The team trains in Tampa.) Savage’s raspy rendition of “’Twas the Night Before Christmas” was something to behold. He also made numerous appearances on behalf of D.A.R.E., Habitat for Humanity and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Savage fights a losing battle with Jamason McMillion, 10, of New Port Richey.

Image: Zuma Press

Savage loved dogs. He owned several in his adult life, but none were as beloved as Hercules, the German Shephard that wrestler Hercules Hernandez gave him.

“The only time I ever saw Randy break character was when his dog got parvo and died,” Rogers says. “After that, he kept a wooden home plate on the wall with the dog’s tags and a picture of the dog.” Not long before his own death, Savage had his brother Lanny spread Hercules’ ashes over a tree in Savage’s backyard. He asked his brother to do the same with his own ashes.

After reconnecting in the early 2000s, Savage and Lynn Payne were married on the same stretch of Lido Beach where they met almost four decades prior.

Image: Tim Boyles/Getty Images

The greatest joy of Savage’s retirement came when he rekindled his relationship with Payne. Both divorced, Payne and Savage became reacquainted in the early 2000s and soon became a couple again. They married on May 10, 2010, 38 years after they first met.

“The real love of his life was Lynn,” says Rogers. “You always go back to your first loves.”

But the couple’s new life together was short-lived. One year and 10 days after their wedding on Lido, Savage experienced a heart attack while driving in Seminole, Florida. Payne steered their Jeep Wrangler out of oncoming traffic and sustained only minor injuries, but by the time help arrived, Savage was gone. He was pronounced dead at Largo Medical Center on the morning of May 20, 2011. The coroner found that Savage had an enlarged heart, which blocked his coronary arteries. Adhering to Savage’s wish, Payne and Lanny scattered half of his ashes over the tree where Hercules’ ashes had been spread just a few weeks earlier.

After news of Savage’s death became public, tributes poured in from the wrestling, sports and entertainment world. Wrestler and action star John Cena called him “one of the all-time greats,” while wrestler “Stone Cold” Steve Austin said he was “a hellacious performer” and “a real badass.” Sportswriter Bill Simmons dubbed him “one of the greatest pro wrestlers who ever lived.”

“Randy didn’t have a lot of friends, because he was always transient,” Rogers says. “But I don’t think there’s anybody I loved more in this life as far as a guy.” Rogers credits Savage with teaching him the Poffo family work ethic, which in turn helped Rogers become a champion competitive bodybuilder. Thanks to Savage and ICW, Rogers, who’s now 69, also learned the ins and outs of the wrestling business, going on to serve as the chief booker and promoter for several major wrestling promotion companies. When we spoke, he was working out on an elliptical bike after nearly three hours of training.

“I wouldn’t have done this if I hadn’t met Randy,” Rogers says. “He taught me how to get good. He taught me confidence. He didn’t have to say anything. He did it just by hanging out.”

Clayton Trutor teaches history at Norwich University in Vermont. He is the author of Loserville: How Professional Sports Remade Atlanta—and How Atlanta Remade Professional Sports (2022) and the forthcoming Boston Ball: Jim Calhoun, Rick Pitino, Gary Williams, and College Basketball’s Forgotten Cradle of Coaches (2023). Follow him on Twitter @ClaytonTrutor