Longtime Sarasota Resident Hoyt Wilhelm Threw the Most Mystifying Pitch in Baseball

The whole idea of a knuckleball is to throw a ball that doesn’t spin. It goes up there to the plate dead,” Hoyt Wilhelm explained to CBS Sunday Morning’s Charles Kuralt in April 1994. The famed television journalist was exploring the history of baseball’s most mystifying pitch by speaking with its greatest purveyor. Few pitchers built their career around the unpredictable pitch, which frustrated hitters, seemingly dancing away from the outstretched bats of hitters who were used to matching the power of hard throwing pitchers with similarly combustible swings. But Wilhelm did.

For a little more than the last quarter century of his life, the most unlikely member of the Baseball Hall of Fame called Sarasota home. In a sport dominated by the boys of summer, Wilhelm didn’t get his shot at the big time until he was thought of as middle aged. He was nearly 30 years old at the time of his Major League Baseball (MLB) debut and he was nearly 50 when he played in his last game. He was a pitcher, but a career relief pitcher—not a starting one like every other hurler selected for the Hall of Fame before him. He didn’t throw hard or throw a nasty curve ball. He relied on the knuckleball, a pitch as unpredictable as the trajectory of his one-of-a-kind career. He was known simultaneously as baseball’s best reliever, baseball’s best knuckleballer, and baseball’s best old player for the lion’s share of his career.

Still, for all of his success, Wilhelm remained humble. In retirement, he lived quietly, just as he always had: surrounded by family and the game that he loved.

“He was just a regular guy. No pretensions at all. If you met him on the street, you’d think he was a farmer,” Mike Luongo, a lifelong baseball fan originally from upstate New York, said of his friend. Luongo got to know Wilhelm at a series of fantasy baseball camps the former big-league pitcher worked during the late 1980s and 1990s. The pair struck up a friendship.

Luongo’s impression of his friend, that he just seemed like a farmer, was reflective of the Hall of Famer’s childhood in the Tarheel State.

James Hoyt Wilhelm was born on July 26, 1922 in Huntersville, North Carolina, then a town of roughly 800 in Mecklenburg County. Since the year 2000, Huntersville has exploded into a bedroom community of more than 40,000 due to its proximity to Charlotte.

“He was a country kid from North Carolina who just enjoyed baseball,” Brett Honeycutt said. Honeycutt is a sportswriter from Charlotte, North Carolina, who has written extensively about Wilhelm and operates a Hoyt Wilhelm Fan Page on Twitter. On several occasions, Honeycutt got to meet his hero, including in Sarasota. Honeycutt has done as much as anyone to spread the story of one of baseball’s most odds defying stars.

Hoyt’s family were tenant farmers in Tobacco Country. John and Ethel Wilhelm raised their 11 children in hardscrabble circumstances, but built them a firm foundation steeped in their Presbyterian faith. Hoyt and his family remained close throughout his life and many of his siblings stayed in the Huntersville area.

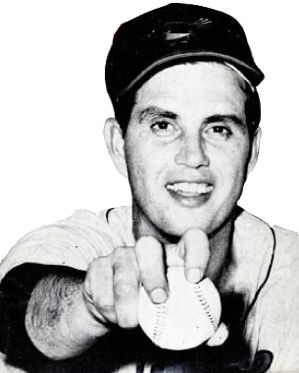

Hoyt Wilhelm demonstrating the pitch that made him famous in 1959.

Image: Wikipedia

Wilhelm learned the pitch that made him a Hall of Famer in high school. Initially, he emulated the finger positioning he saw in photographs of Washington Senators knuckleballer Dutch Leonard. He experimented with the pitch in his early teens, impaling his index and middle fingers into the ball rather than relying on his knuckles, as the pitch’s name suggests. He showed an immediate knack for the knuckleball, becoming the ace on the local Cornelius High School baseball team.

Working closely with his high school coach, Ben Brown, Wilhelm started throwing the knuckleball exclusively during his senior year. By the time he graduated, he'd earned the reputation as one of the area’s best pitchers.

Wilhelm showed enough promise in high school to earn a spot in 1942 with the Class D North Carolina State League team in nearby Mooresville. Initially, he struggled and was released, but took advantage of a second chance. Later in life, he often called upon the experience of being released from the lowest level of professional baseball. When coaching young pitchers in Sarasota for the Yankees, or when he was put in the unenviable position of telling players they had been released, Wilhelm could encourage young men to be persistent in pursuit of their dreams because he had done just that.

After his first year of minor league baseball, Wilhlem was drafted and spent the next three years serving his country in the U.S. Army. He earned two Bronze Stars and a Purple Heart for his service, which included combat at the Battle of the Bulge. Shrapnel from the enemy artillery blast that earned him the Purple Heart stayed lodged in his right hand (which was also his pitching hand) and in his back. Like many in his generation, Wilhelm shied away from discussing his military experiences, so not much else is known about his Army career.

He returned to Mooresville in 1946 and continued on a minor league baseball odyssey that lasted seven seasons, advancing slowly but surely through the New York Giants minor league system. In 1948, he met his wife in Columbus, Georgia. He spotted Peggy Reeves in the stands at Golden Park and asked an usher to get her phone number. The two kept up a correspondence for several years and were eventually married in 1951. Peggy became a baseball lifer when she married Hoyt, just as his minor league odyssey was about to become a Major League one.

In need of relievers, New York Giants manager Leo Durocher gave Wilhelm his big league shot in 1952, as the pitcher approached his 30th birthday. Wilhelm took advantage of the opportunity, winning 15 of his 18 decisions, posting 11 saves and a 2.43 Earned Run Average—the best in the National League.

This rookie standout baffled teammates and opponents from the outset, as he was already older than virtually everyone on his team. Moreover, Wilhelm never threw particularly hard and relied almost exclusively on his knuckleball. Much of the success of the knuckleball lay in its unpredictability—the pitch danced and dropped from its original trajectory on its way towards home plate. Later in Wilhelm’s career, his catchers started using oversized mitts to prevent pitches from getting past them.

In 1954, Wilhelm helped lead the New York Giants to their first World Series championship since 1933. Later in the decade, he was traded to the Baltimore Orioles, who used him for several years as a starter, despite being known as a reliever.

Wilhelm's greatest moment on the mound came in late September 1958, early in his tenure as a starter. In just his third game as an Oriole, he threw a no-hitter against the New York Yankees, who were in the midst of one of the greatest championship runs in baseball history. Less than a month after Wilhelm no-hit the Yankees on the nationally televised Game of the Week, New York captured the franchise’s 18th World Championship.

Wilhelm continued to pitch as a starter for the Orioles for several seasons before returning to the bullpen full-time with the Chicago White Sox, enjoying arguably the best stretch of his career in his early 40s. He seemed to get better with age. He wound up pitching for nine different teams and being a highly sought-out reliever well into middle age. All told, he made the All-Star Team eight times. He was the all-time leader in saves and pitching appearances at the time of his retirement in 1972, when he was nearly 50 years old.

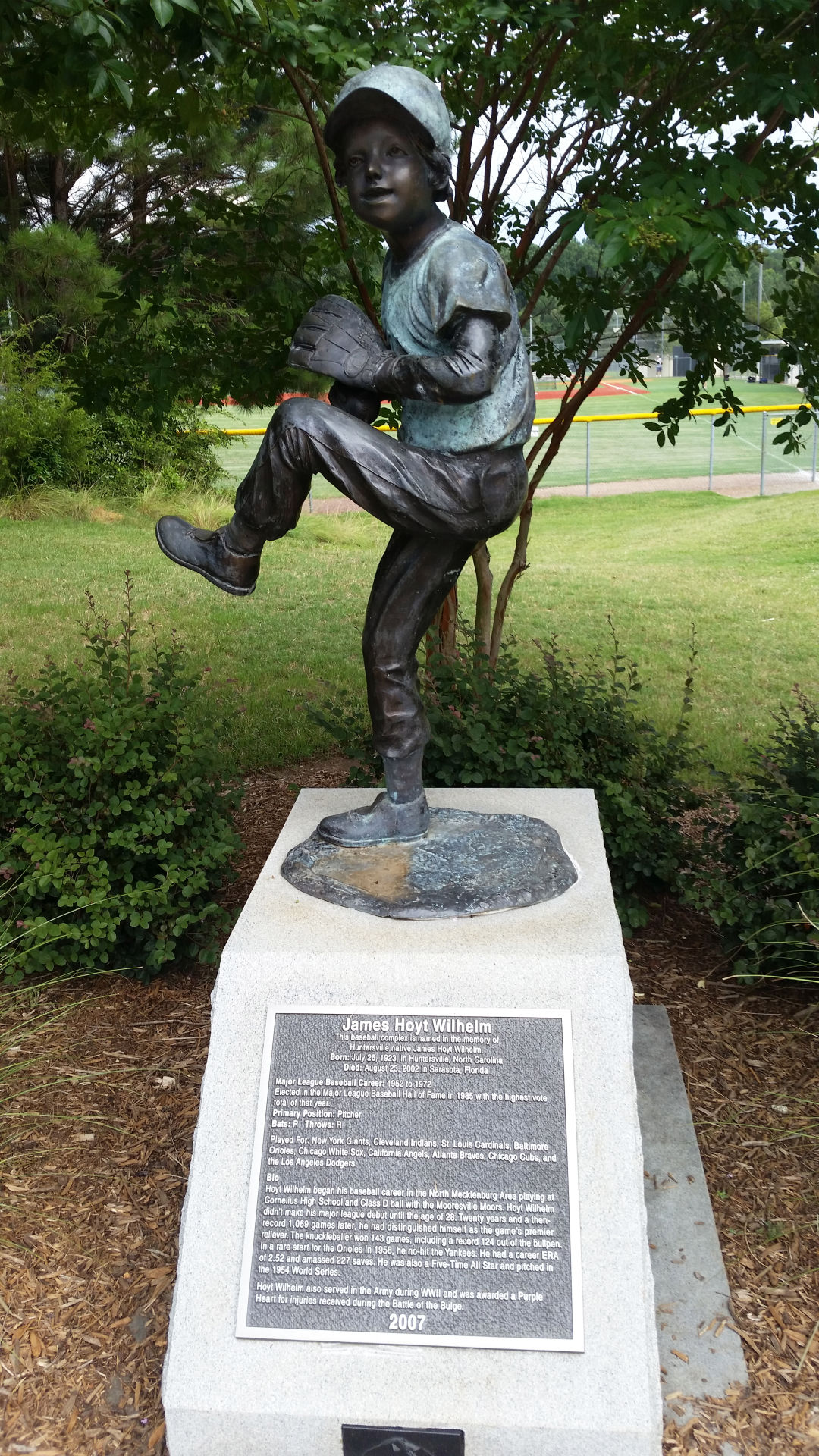

James Hoyt Wilhelm Commemorative Statue outside Huntersville Athletic Park in Huntersville, North Carolina.

Image: DMagee33/Wikipedia

Wilhelm’s oft-discussed longevity was due, in large part, to his use of the knuckleball, which didn’t rely on the power or torque employed in other pitches. It was likely also the result of the lifestyle he led. Wilhelm was a quiet man who led a quiet family life. Never a carouser, he and Peggy raised their two daughters and son during the off-season first in her hometown of Columbus, Georgia, then in Sarasota, with frequent trips back to Hoyt’s farmstead in Huntersville. In later years, Hoyt and Peggy were kept busy by their 12 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. Peggy cooked him mid-afternoon steak dinners before games and fed him ice cream when he got home. In his free time, Wilhelm spent many quiet evenings watching movies with his wife or going on walks, his primary source of off-season exercise.

After his retirement, Wilhelm managed in the Braves organization for a couple of seasons before taking a position with the Yankees. He and his family moved to Sarasota in 1975, and Wilhelm worked with the Yankees of the rookie Gulf Coast League and also as a roving instructor in the Yankees minor league system for most of the subsequent two decades. The family lived on the water on Hudson Bayou and enjoyed its unparalleled boating and fishing. But baseball continued to play a profound role in Hoyt’s life.

Despite being well known for throwing the knuckleball, Wilhelm shied away from teaching the pitch, believing it was a gift that pitchers were born with rather than something they could acquire. Instead, he focused on the tactics and strategy of the position. He tried to help pitchers improve the pitches they did have while imparting some of the guile that helped him stay in the big leagues for more than 20 years. Future MLB standouts, including Ron Guidry, Dave Righetti, and Sterling Hitchcock, credited Wilhelm with helping them learn to pitch at the big-league level.

“The greatest joy I get is in seeing those kids go up to the big leagues. I wish they could all experience it,” he told the Columbus Ledger in 1991.

Brett Honeycutt remembers attending a Sarasota Yankees game on what happened to be Wilhelm’s birthday. Several years earlier, a middle-school-aged Honeycutt and his father met Wilhelm when the knuckleballer was a pitching coach for the Nashville Sounds minor league baseball team. Wilhelm had taken the time to autograph a fistful of Honeycutt’s baseball cards, .and made time for him again in Sarasota. The pair had their picture taken together that evening.

“His family always came to visit him at the games,” Honeycutt recalls, including Wilhelm’s siblings and cousins. In later years, Honeycutt got to know members of the Wilhelm family in North Carolina. He helped get a park named after Wilhelm at the site of the Hall of Famer’s former high school in Cornelius and also created a plaque to honor him at the site.

In the off-season, Wilhelm spent much of his time in the woods of North Carolina and Florida hunting, always working with the trusty hunting dogs that he trained himself. In retirement, he became an avid golfer, rekindling an interest he’d had as a younger man in North Carolina but dropped during his Major League career. For years, he played in many Sarasota-area fundraisers for youth baseball programs alongside other local former MLB players. He also worked on behalf of United Cerebral Palsy of Sarasota-Manatee and asked for donations to be made to the organization in his obituary.

Wilhelm took great pleasure in participating in fantasy baseball camps, which enabled fans to play alongside former MLB players. Randy Hundley, a former Chicago Cubs catcher, created the concept of fantasy baseball camps in the early 1980s and invited Wilhelm to participate. Wilhelm was a fixture at Hundley’s camps in Arizona and at the Chicago White Sox’s facility in Sarasota during the 1980s and 1990s.

Mike Luongo first attended a Randy Hundley Fantasy Camp in 1987 and got hooked on them. Luongo was a longtime college and high school baseball umpire originally from Orange County, New York, who made his career in the bowling industry. He appreciated Wilhlm's low-key sense of humor and easy-going manner.

“He was funny in a unique way. Not loud and joking. He was a quiet guy with good one-liners and fun to socialize with, though he didn’t stay out too late,” Luongo recalls. Wilhelm had taken up woodworking as a hobby and even made his new friend a lamp crafted out of a baseball bat.

“He took a baseball bat, cut it in half, ran some kind of long dowel through, drilled a hole in a baseball, and signed the baseball,” Luongo says.

In 1985, Wilhelm became the first relief pitcher inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. While some baseball writers were initially hesitant to induct a “part-time player” like a reliever, several champions in the sports writing fraternity, particularly New York-based sportswriter and author Leonard Koppett, helped persuade more than the requisite 75 percent of voters in the Baseball Writers’ Association of America to vote him into the Hall of Fame. Wilhelm’s wife, children, grandchildren, and six of his sisters attended his induction ceremony. In typical Wilhelm fashion, he spoke of faith, family, and perseverance during his induction speech.

As the 20th century turned into the 21st, Hoyt Wilhelm’s health began to deteriorate. Heart trouble and diabetes slowed him in his later years. On August 23, 2002, he died at the age of 80 in Sarasota. He was mourned widely in baseball circles and lauded as one of the unique talents in the history of the game. A simple grave marker in Palms Memorial Park in Sarasota honors his life of His wife Peggy died in 2015 and is buried alongside him. The words “Precious Peace” are inscribed below Peggy Wilhelm’s name and dates on her tombstone. It is tough to imagine a phrase that better encapsulates the life that the famous knuckleballer and his family led in Sarasota over the last quarter-century of their lives together.

Clayton Trutor teaches history at Norwich University in Vermont. He is the author of Loserville: How Professional Sports Remade Atlanta—and How Atlanta Remade Professional Sports (2022) and the forthcoming Boston Ball: Jim Calhoun, Rick Pitino, Gary Williams, and College Basketball’s Forgotten Cradle of Coaches (2023). He’d love to hear from you on Twitter: @ClaytonTrutor

Opening photo: David Durochik/AP