Entrepreneur Lillian Lambert on Being the First Black Woman to Graduate from Harvard Business School

This article is part of the series In Their Own Words, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

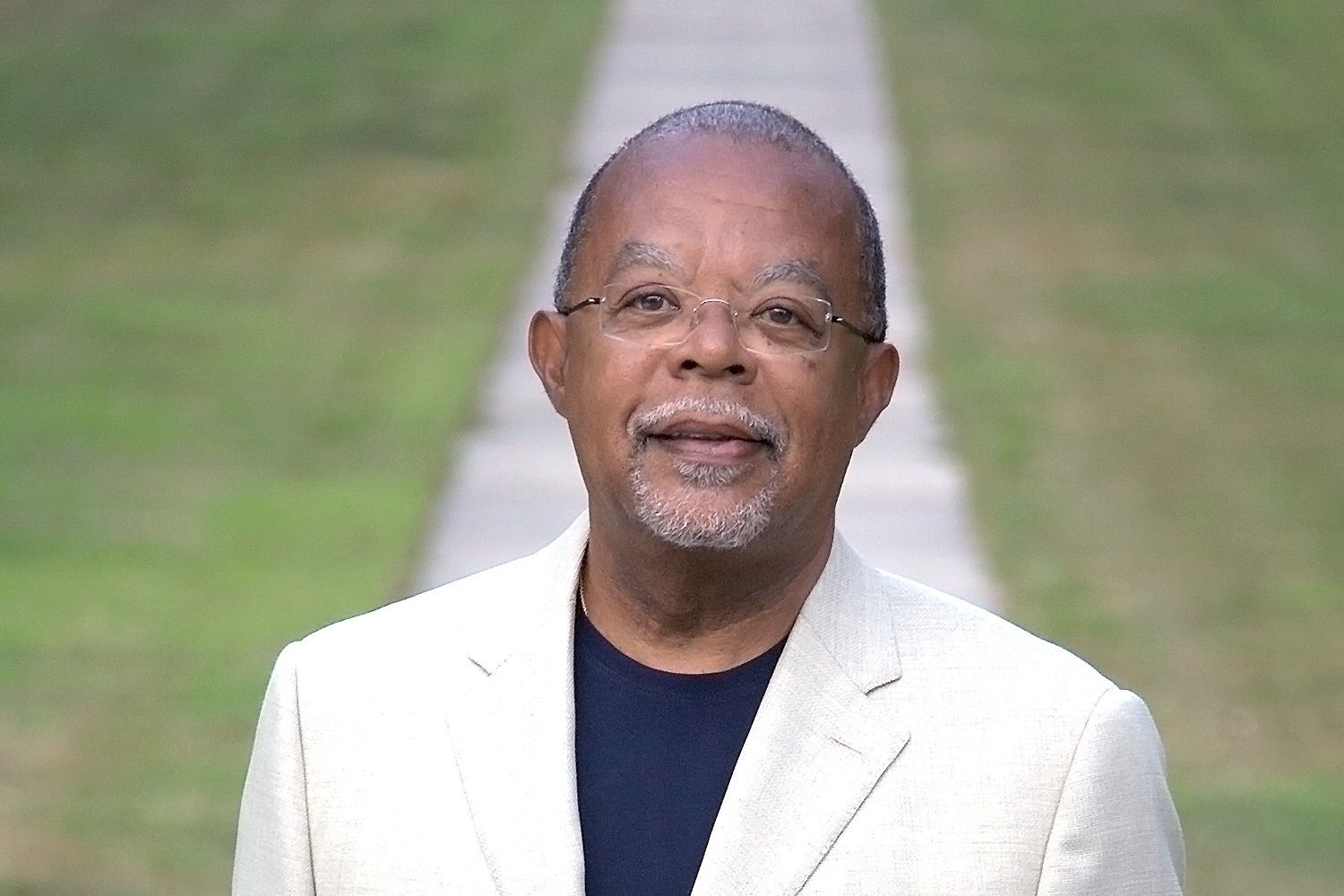

Lillian Lincoln Lambert

Image: Michael Kinsey

Born in Ballsville, Virginia—population: 250—part-time Sarasota resident Lillian Lincoln Lambert transcended small-town life and went on to become the first Black woman to graduate Harvard Business School (HBS).

Lambert's resume includes roles as an entrepreneur, coach, speaker and author—she recently released her autobiography, The Road to Someplace Better: From the Segregated South to Harvard Business School and Beyond. However, she began her professional life right out of high school with jobs as a maid in New York City until she realized she needed more education. From there, Lambert went on to Howard University for her bachelor's degree, then to Harvard for her MBA.

Six years later, Lambert broke into in the male-dominated industry of building maintenance service. In 1976, she launched Centennial One, which grew to a $20 million enterprise, operating in six states with more than 1,200 employees and offering services ranging from carpet cleaning to landscaping. Lambert was first female president of the Building Service Contractors Association International, Maryland’s Small Business Person of the Year in 1981, and received Harvard's Alumni Achievement Award—the highest award the school bestows on its graduates—in 2003.

Lambert sold Centennial One after 25 years, and now, at 82, is retired but still takes on speaking engagements. She and her husband, John Lambert, Sr., split time between their condo in Sarasota and home in Richmond, VA.

Talk about growing up in the segregated south.

"It was not extremely difficult, but you could see the signs of the way things were in terms of segregation. There was an undercurrent of that energy. And white people didn’t mind letting you know that they thought you didn’t belong.

"Our parents and teachers cared about us becoming all-around good citizens, and they prepared us for the segregated world. We had to be better to compete on equal basis because we were not expected to be successful. The Black kids walked to school while the white kids rode the bus. I didn’t ride bus until seventh grade and schools were not integrated until after I graduated high school. I was one of 28 students in my graduating class."

How did your parents influence you?

"My parents, Arnetha Bertha Hobson, a graduate of Virginia State University, and Willie David Hobson, who had a third-grade education, were involved in the NAACP and voter registration. My father voted because it was important, even though he didn’t write. He used an “X” to mark his signature. However, he never wanted to work for someone else and was a proud farmer who owned 30 acres of land, which he purchased for $500. in 1928.

"My family went to church on a regular basis, which was the center of our social lives. We were happy as kids there, because we didn’t know any other type of life."

What brought you to New York City?

"I didn’t know that there was something better than working on the family farm until I noticed relatives who came home from New York City and looked prosperous, driving nice cars. It seemed so glamorous. All I wanted to do was move there and become a secretary, but it didn’t dawn on me that because I only had a high-school diploma, I could only find work as a maid. However, it exposed me to people who made money, and I liked what I saw.

"Until you’re exposed to life outside of the segregation system, it doesn’t dawn on you that more exists. That’s why travel is important for everyone. It exposes you to other cultures and improves your own life."

Who inspired you to apply to Harvard Business School?

"My Howard University professor, H. Naylor Fitzhugh. He graduated from Harvard Business School in 1933 and was one of first Black men to do so. He may have known that I would be the first Black woman, but in hindsight, it was better that I didn’t.

"Prof. Fitzhugh couldn’t get a corporate job because he was Black, so he taught at Howard. It may have been a disappointment for him, but it was a blessing for his students. He influenced so many lives. Later in life, he did get a job at PepsiCo."

What did your parents think?

"My dad was so proud. He would tell everyone that ‘Lillian is going to the same school as President Kennedy.’ He didn’t see me graduate because he passed away my first year at Harvard. But it’s amazing to me that it only took a single generation for our family to go from sharecroppers to me as a graduate of Harvard Business School."

What was it like for you when you arrived at HBS in 1967?

"First, it’s important to note that my first Harvard application was rejected. I didn’t take it seriously; I didn’t want to attend. I was doing it at Prof. Fitzhugh’s suggestion. However, once I learned that I was not accepted, it made me mad. If he said that I was Harvard material, then why didn’t I get in?

"I contacted the school and learned that I did not score high enough [on the entrance exam]. Well, it made sense because I just took the test; I didn't prepare. So, I retook it and reapplied, but that time, I was ready.

"Arriving at Harvard was a shock similar to arriving in NYC. I had not visited before I applied. The business school didn’t accept women until 1963, and even then, they were not prepared because the dorms were designed for male students. My dorm was at Radcliffe College, a women’s college, at 6 Ash St., which is where most of the female students from various schools lived. From there, I had to walk a half-mile to class.

"When I got to the dorm, I had a travel trunk. The lady who opened the dorm greeted me, but my room was not ready. So, I went to a park down the street with my luggage to wait. I remember that I kept asking myself, ‘Why am I here?’ At that point, I just wanted to get my suitcase and go home. But then I thought about all the people that I would disappoint if I quit. I couldn’t. I had a responsibility to do this."

Did a Black community exist at Harvard?

"At registration, I did not see one Black person and only a few women. In my class of about 800 students, 18 were women and six were Black: five men and me.

"At the time, Harvard broke the 800 students into sections, with no more than two women in each section. And there were no Black students together. It took a while before I met the others. One was Roy Willis, a graduate of the University of Virginia where he experienced racism and a lack of Black students, as well. He thought that Harvard would be different, but he noted that there really was no difference.

"Willis went to admissions and asked why there were not more Black students. He got pushback. They told him that he should be happy that he was there. But he persisted and when he met the rest of us, he told us that this standard was not right, and we needed to do something about it."

What did you do?

"We met with the business school’s dean, George Baker. We didn’t know if he would be receptive or kick us out, but we thought that it was worth a chance. Dean Baker was a big, overpowering guy who stood more than six feet tall. In his office, he had a big oval table instead of desk, where we sat. He was attentive and listened to everything we said. By the time we left, the school agreed to send us to each of our former universities to recruit Black students. And he promised to go to corporations for scholarship money. He delivered on his end, and we delivered on ours.

"The following year, Black student enrollment went up from six to 27, and all graduated. Once this happened, we decided that the school needed a support system for these students. We started the African American Student Union, a space where Black students could find not only support but resources for everything from barber shops that cut Black hair to churches."

Does the African American Student Union still exist?

"Yes, it was school-sanctioned and is still in existence today. The 50th anniversary was in 2018. Three of the five living founders attended the two days of activities surrounding the anniversary. And we were awarded the W.E.B. DuBois Medal by Dr. Henry Gates, which is Harvard’s highest honor in the field of African-American studies. It's been bestowed upon people like Oprah Winfrey, Muhammad Ali and Denzel Washington."

In 2003, the school awarded you the Alumni Achievement Award, the highest honor for alumni who are exemplary role models in business and their communities. How did you feel about this?

"What’s interesting is that when I left the campus in 1969, I promised myself that I’d never set foot on the university grounds again. Those two years were difficult and lonely; I did not enjoy my time there. Yet, again, Prof. Fitzhugh intervened. He reminded me that it was my responsibility to support the Black students who came behind me. I knew he was right, and I did. I got so much out of it the more I became involved."

Tell us about launching your building services business, Centennial One.

"I had no intention of being an entrepreneur. The reason that I started my own company is because a friend put the thought in my mind. I liked my job and employer [Unified Services], but realized that [starting my own business] may not be a bad idea. I began doing it on the side, part time, while I kept my full-time job. However, I didn’t want Unified Services' owner to hear about what I was doing from someone else, so I shared my plans.

"He wasn’t happy at the thought of me being his competitor, but I assured him that there was plenty of business for us both, and that I could get my own contracts. He didn’t want to find replacement, because he said that I was the smartest person he knew, so he was willing to deal with it. A week later, he called me into his office and said that he'd had a meeting with board of directors—which I believe was his wife—and that Friday was my last day. I replied, ‘Then why don’t I leave tomorrow?’

"My husband and I were a two-income family with two small kids, so I had to make my company work, and fast. I gave myself six months to get my business started. It got off the ground at nearly month five. I got my first contract just in time."

How did you build your business?

"I concentrated on government contracts through the 8(a) program, which helps minorities capture new opportunities from the government. I knew a guy who worked there, and he helped me get the paperwork done. But the program rejected my application. After I pushed back, they told me that they would approve me if I could provide evidence that I could get my own contracts. I don’t know anyone else who had to provide this information.

"However, while my launch was underway, I was contacting companies to let them know that I was building a business in the industry. Therefore, I was able to provide the government with that list and I was ultimately accepted.

"Over time, I found that there were very few women in the industry. It was mostly white men. The women did the cleaning, the men ran the companies."

How do you feel about Harvard’s recent announcement to reckon with the fact that its leaders and staff enslaved 79 people in the 17th and 18th centuries?

"I have not read the full report. I am, however, encouraged by an email from HBS dean Srikant Datar, informing alumni about it. I'm pleased that Harvard is willing to invest human and financial resources to research slavery by looking at the extent of the school's involvement, how the university benefited from slavery and its impact on future generations.

"A positive and public move forward was the renaming of the house of an active segregationist to the Cash House, named after Dr. James Cash, the first black tenured professor at HBS. This move may encourage other universities to act to face the realities of slavery."

What would you like your white friends or acquaintances to be doing right now?

"Learn more about experiences that the Black community has gone through, and to some extent still going through. Also, open doors for our community, as well. Mentorship is critical. Consider the impact it made when a white mentor opened doors for you—places you may not have been able to reach unless someone helped you get there.

"And be more understanding and knowledgeable. Call out acts of racism or violence. Too many times, white people will say something and others let it go. Don’t be ashamed of where you stand. Speak up."

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill