Mr. Chatterbox: The Strange Story of Huguette Clark

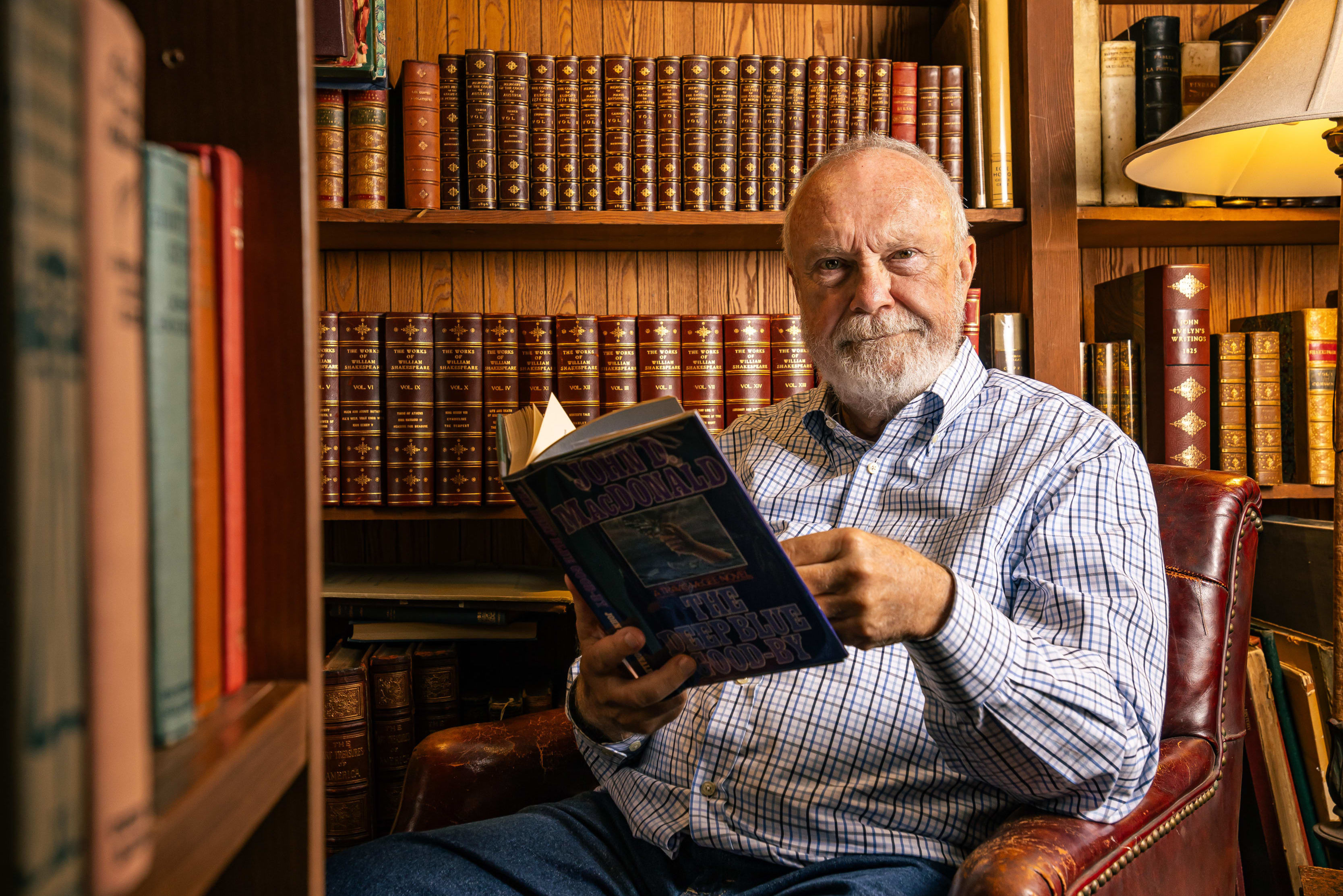

The literature of retirement, I've discovered, is lousy. It advocates the same obvious messages: Take care of your health, keep busy, preferably by volunteering, and become a gregarious, social human being, reaching out to family, friends and connections. Since I've never done any of these things, I'm stymied. What am I supposed to do? Turn myself into a whole new person? Isn't there a little room for eccentricities?

That's why I've become so obsessed with the life of Huguette Clark, the incredibly rich woman who spent the last 20 years of her life living in a hospital room even though she wasn't the least bit sick. She passed the days by playing with dolls and watching her collection of Smurf cartoons. Of course, your mind goes immediately to "completely gaga," but this wasn't the case at all.

She was sharp as a tack. She was in control of her financial affairs. And she was a genuinely nice person. She just wanted to live a certain way and had the money to make it happen.

According to some stories, the hospital spent the entire 20 years scheming to get its hands on her money, making fun of her behind her back as a simple-minded old woman who played with dolls. Hardly. She wasn't playing with dolls out of regression to childhood. She was an expert on the subject, the owner of the best doll collection in the world. She had all sorts, from antique European porcelain dolls to up-to-date Barbie dolls. Her favorites, though, were Japanese dolls, for whom she would design classical Japanese palaces and tea houses, complete and historically accurate down to the furniture and the dishes. After spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on one of these miniature settings, and waiting two years for it to be completed, she would look at photographs of it for an hour or so in a state of heavenly bliss, sigh happily, and then go on to the next project.

Now I admit that the Smurfs did throw me off for a moment. Doll collecting I can understand; Smurf watching not so much. Then I found out she not only watched the shows over and over, she had transcripts made. That's when I realized her true genius.

You have to be a very smart person to appreciate the Smurfs on an intellectual level—how they fit into the tradition of dolls and folk characters, how Smurf episodes deal with plot and character development and moral dilemmas. It must be a fascinating intellectual obsession. (Of course, there's always the possibility that she just really, really liked the Smurfs.)

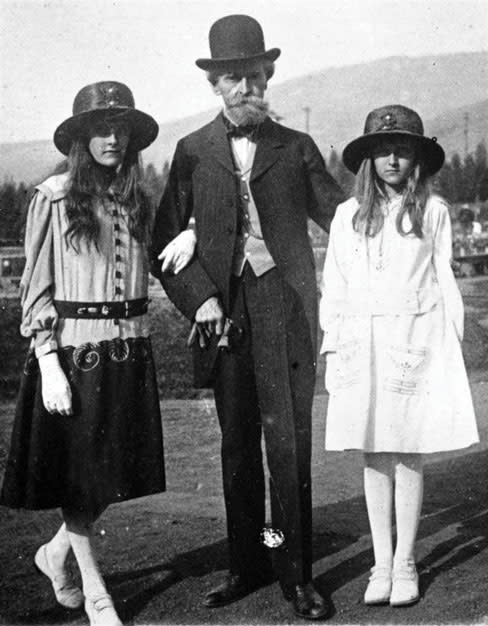

People seem to be perplexed about why she chose to live this way, but I understand it completely. Her father, William Clark, had been a famous robber baron from the early 1900s, who made a fortune in copper and built the largest private home in New York City. She grew up as a rich girl—private schools, trips to Europe, a brief marriage. But there was always something very reserved about her. Social life didn't appeal to her, and while she enjoyed cultural pursuits—painting and music—she tended to stay home more and more, with her mother and a few close relatives for company.

But the relatives died, and by her mid-80s, Huguette had become a recluse in an enormous Fifth Avenue apartment, malnourished and suffering from untreated skin cancer. She had outlived all her doctors. A friend finally became aware of the situation and put her in Beth Israel Hospital, where a strange thing happened. She came alive again.

She had stumbled into her perfect living situation. Her luxurious homes—she owned five—meant nothing; she preferred the security and simplicity of a standard-issue hospital room. It was her cocoon. She had plenty of money to pursue her hobbies and interests, and figured out a way to do it all from a hospital bed. Her relatives didn't even know she was there, and that was just the way she wanted it. They were mostly distant cousins, and the family ties had pretty much vanished—for her, anyway, although I can imagine how interested they might have been in the health of their dear Cousin Huguette, with $300 million and no direct heirs.

But she was never lonely. There was always somebody to talk to and take care of her, and that leads to perhaps her greatest achievement—she created what sociologist call a "fictive family." That's when a group of people who are not related bond together and offer each other support, both emotional and financial, the way a blood family would—or at least should.

The core of the family was her nurse, Hadassah Peri, who, despite her name, was from the Philippines. Hadassah was assigned to Huguette completely by chance, but the two women clicked. Hadassah seems like a nice and devoted person. She worked a 12-hour shift without a day off for years. But still, you can't help but wonder how she really felt, because, over the years Huguette gave her $31 million.

Yes, that was the secret to Huguette's fictive family: money. She showered them with cash and presents. Houses and apartments and automobiles were bought for them, tuition was paid for their children's schools, enormous checks were written as Christmas presents. Hadassah got several checks for $5 million each. Huguette's assistant, a guy named Chris who kept her doll collection organized, also got several million. Other beneficiaries included her lawyer, her accountant, and a goddaughter she hadn't seen in years but who wisely kept in touch via poems and letters.

Was Huguette being exploited or was she getting good value for her money? This leads to the question of who should get a rich person's money—the blood family with whom she had no contact and didn't particularly like? Or the fictive family who made her final years so happy?

Huguette finally died in 2011 at the age of 104, and because of two conflicting wills she had drawn up—one favored the blood family, the other the fictive family—the courts had to decide. Just before the case went to trial a settlement was reached, in which everybody got something. The cousins, 30 of them, each got about a million. Hadassah, who perhaps was a little greedy, had to give $5 million back, which she did cheerfully enough, and why not, since she was still the richest nurse in the world. Most of the money went to establish a foundation for the arts.

The big loser was the hospital, I'm glad to report. Their years of scheming netted them a paltry million dollars, not the $125 million they were hoping for. For all her generosity, Huguette knew how to say no. Whenever the top brass came down to visit her in her room, after exchanging pleasantries they would steer the conversation around to how much money she was leaving them. Huguette would say she'd think about it. Then she'd put on the Smurfs.

That cleared the room pretty quick.