For Architect Frank Folsom Smith, the 1966 Plymouth Harbor Retirement Center Was the Project of a Lifetime

Frank Folsom Smith lives in one of the prettiest homes in Sarasota. It is also one of the oldest, a farmhouse from the late 1800s, reinterpreted to stylish perfection. It’s set on the bay in Indian Beach, hidden away down a narrow lane and on an acre or so of green lawn that runs down to the water. A collaboration with his wife, Anne, a prominent interior designer, it’s more traditional than you might expect (Anne’s influence), but with plenty of sleek modern touches that are pure Frank Folsom Smith. The house sits on an ancient Indian midden; and Smith, who is part Presbyterian and part New Age spiritualist, says he can feel the energy flowing back thousands of years.

Chances are the architect is in the kitchen, preparing coffee. Others make coffee; Smith prepares it, like the Japanese do tea. He is meticulous and follows a process with many steps. More than one pot is used. There is a hooded warming device. He is excited that a Starbucks is moving in, just a five-minute walk away. Coffee, along with basketball and cars, has long been among his greatest pleasures.

Smith recently turned 87. He’s a little stooped, but his eyes are sharp and don’t miss a thing. His memory and sense of humor are equally keen, and he still has his Virginia-bred charm. He also has all his hair, a distinguished gray/white. He looks every inch of what he is—the Grand Old Man of Sarasota architecture.

Frank Folsom Smith’s Sandy Cove condominium featured a pioneering mix of low- and mid-rise buildings.

Image: Courtesy Frank Folsom Smith

You can see his work all over town, all over the country, in fact. Locally there are Sandy Cove (featured on the cover and in an 18-page story in Southern Living in 1971) and the Terrace on Siesta Key; Pine Run and Rivendell in Osprey; the U.S. Garage and Burns Court restorations downtown; and Conrad Beach on Longboat. Go farther afield and you’ll find his work, from single-family homes to large mixed-use communities, in places from Virginia to California.

Smith was also a driving force behind R/UDAT, a pioneering design workshop in 1981 that drew planners from across the country to Sarasota and helped lay the foundation for the dynamic downtown development of downtown.

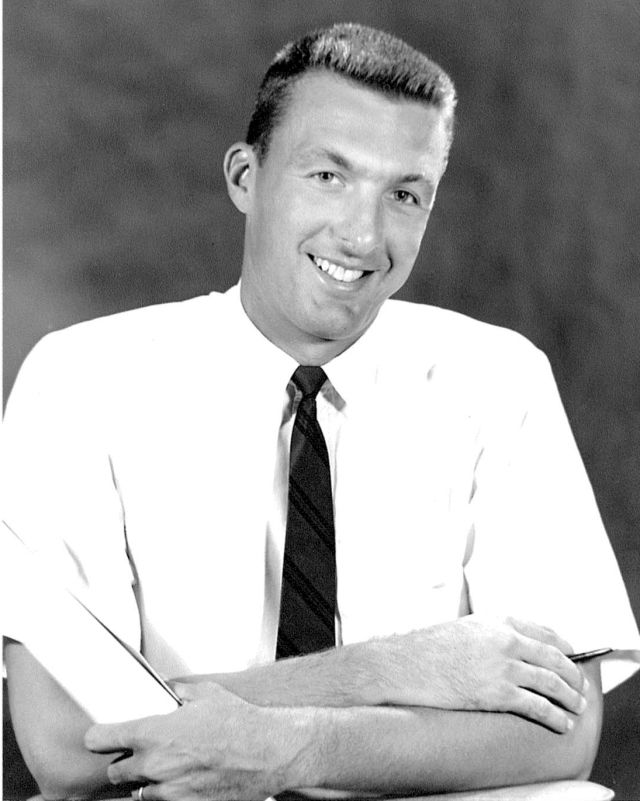

Smith as a young architect.

Image: Courtesy Frank Folsom Smith

His personal life has been just as eventful. He’s been a college athlete, Army officer, husband, father, grandfather and great-grandfather. He’s won a bookcase full of awards and commendations, and his library is packed with books about other architects, many of whom he knows. He sang a duet with Ella Fitzgerald, played touch football with Bobby Kennedy and spilled a drink on the Prince of Wales. He’s hung out at Esalen, starting in the ’60s, sharing hot tubs with New Age gurus and celebrities like Monty Python’s John Cleese.

But ever since elementary school, when he saw a Frank Lloyd Wright home on the cover of a magazine, he’s been in love with modern architecture. With a master’s degree from the University of Virginia School of Architecture, he began his career in Sarasota in the early 1960s, when a group of gifted young architects were creating buildings in a modernist style that would come to be known as the Sarasota School of Architecture.

Smith shared their penchant for clean lines; simple, honest materials; and seamless integration with the surrounding landscape. But he has designed in a variety of styles, from a beach home that blends Polynesian and Cracker influences to reimagined historic and industrial structures. He designed homes, commercial buildings and churches; he was an architect and then an architect-developer; and for the last few decades, he has poured most of his time and thought into the evolving philosophy of New Urbanism, speaking at conferences around the world.

With his characteristic good cheer, Smith is quick to admit that if he had stuck to one lane, he could have become better known—and wealthier. “But I wouldn’t have done it any other way,” he immediately adds.

This month, Smith’s career is being celebrated during the Sarasota Architectural Foundation’s MOD Weekend, Nov. 8-10. Smith will give a presentation about his work in the 1960s, an explosive decade for architecture and much more in Sarasota. It’s also the decade when Smith, in the lucky break of a lifetime, got the commission to design what is his most iconic building: Plymouth Harbor.

Even if you know nothing about Smith or his work, if you live in or visit Sarasota, you know Plymouth Harbor, the commanding, 250-foot-tall retirement community just off the Ringling Causeway on the way to St. Armands Key. As architectural historian John Howey says, “It was the first building in town to pierce the sky.”

Completed in 1966, it hasn’t lost its power to grab your attention. It’s 25 stories high, made of lowly concrete—there is no steel frame—but with such fine lines and proportions that it comes across as the pinnacle of 1960s elegance. You can see it from all over town, a local landmark if there ever was one. It’s won many awards, including the coveted “Test of Time” from the Florida chapter of the American Institute of Architects. And after all these years it’s never lost its power to surprise and delight.

Plymouth Harbor was a game changer, not only for Smith but for Sarasota. It put our town on the map as a place where innovative scenarios were possible, where new ways of living were being explored and where the can-do spirit of postwar America was at its peak. It was the tallest building in town and still is (if you don’t count those minarets on top of the Ritz-Carlton—a form of architectural cheating). After it was built, the City Commission, momentarily panicked over complaints that we were turning into Miami, passed a height restriction. It was intended as a rebuff but had the ironic effect of making sure that Plymouth Harbor will always be the tallest building in Sarasota.

The Terrace on Siesta Key, another Smith design from the ’60s.

Image: Courtesy Frank Folsom Smith

In 1962, Smith was a young architect trying to find his place in the heady architectural world of Sarasota. It was a small town, fewer than 30,000 people, but architects about to become world famous were working here.

He had already landed a stint working with Victor Lundy, one of the masters of the Sarasota School of Architecture. Smith assisted him with the design of the Warm Mineral Springs Motel in North Port, now considered a landmark of midcentury modernism. And for a while he ran Bill Zimmerman’s office. A gifted designer but a bit of a wild man, Zimmerman was famous for his many open-plan houses that found inspiration in the South Seas. Soon after Smith started working for him, Zimmerman announced he was heading to the Caribbean for an extended sabbatical to clear his head and left Smith in charge.

One of his projects with Zimmerman was the Fellowship Hall at the First Congregational Church. Smith would be out there most days, checking on construction. That’s how he got to know The Rev. Dr. John Whitney MacNeil.

MacNeil, a slight, red-haired man of New England heritage, was an energetic visionary at the pinnacle of Sarasota intellectual life. In addition to his work at his church, he was one of the founders of New College. The minister, well into his 50s, and the architect, barely out of his 20s, struck up a friendship, helped along by the fact that Smith’s senior thesis at the University of Virginia had been the design of a fellowship hall for a Presbyterian church.

“We talked about all sorts of things,” Smith recalls. “History, theology—and of course, architecture.”

One of the subjects of conversation was a dream the minister had—a retirement community, but a new kind of retirement community. There were plenty of retirement communities around, but they were cold, barracks-like places. The main problem with them, MacNeil argued, was that they didn’t foster a sense of community. They might provide adequate care and support, but with their long, dark corridors lined with closed doors, they were not designed to feel comfortable and, most of all, to keep their aging residents connected to neighbors and the world at large.

MacNeil was determined to change that, and he put together a board of local citizens, most of them church members, with the aim of building a place that would keep people vital and happy in their final years. They hired Chuckrow, a big company out of New York, to put the project together. The next step was to choose an architect.

Smith wanted to be that architect. He was captivated by the idea of inventing something new and exciting. By this time, Smith had opened his own firm. He had done several small office buildings downtown, among them the innovative Lawyers Professional Building on Main Street. It was pure Sarasota School in style, with a central patio and fountain. But he knew he was a long shot for the retirement community. Architects from all over the country were vying for the project. Did he really have a chance? For all his bravado, he had never even designed a building with an elevator.

He carefully selected his team for the all-important presentation. It included Lou Schneider, a tweedy, pipe-smoking architect from Bradenton, who had experience in mid-rise buildings and could help with the technical challenges.

Whether it was Smith’s team, his confidence, or the passion he brought to the presentation, he got the job. His relationship with MacNeil helped, of course—and so did Chuckrow’s recognition that Smith was so hungry for the commission that he would do everything possible to make the project succeed.

Smith soon found the ideal location—Coon Key, a 17-acre island in Sarasota Bay. He and the Chuckrow project manager flew over it and marveled at how beautiful it was, with spectacular water views.

Coon Key was owned by the Arvida Corporation, the giant developers who had purchased what remained of the Sarasota properties originally owned by John Ringling. They were developing several at the southern end of Longboat Key in addition to Bird Key, just to the east of Coon Key. Bird Key was a vast undertaking. The entire island was reshaped, with canals added and lots for hundreds of homes.

Coon Key was something else all together. It was unspoiled and undeveloped, surrounded by mangroves, home to birds and native wildlife. Arvida, which was still smarting from public outcry over the massive dredging and filling they had done with Bird Key, consented to sell the island at a very affordable price.

Smith envisioned a tall tower rising on Coon Key. It would be a beacon, a landmark, a “lighthouse” that could be seen from a great distance. MacNeil was very much on board except for one thing. How could a high-rise promote social interaction? Many of the potential residents were from small-town or even rural backgrounds and might see a high-rise as forbidding and cold. Then he remembered the Brown Palace, a hotel he had stayed at in Denver. It had a center atrium with balconies surrounding the inner court. The scale was intimate and the atmosphere comfortable.

Smith and MacNeil refined the atrium concept for Plymouth Harbor, as the new complex was to be named. There would be nine living areas, and they would be called “colonies,” a happy reference to Plymouth Harbor’s early American nomenclature. These small, self-contained communities would be stacked on top of each other. Each would be three stories in height, with the lowest level furnished as a lounge. In this intimate setting, social encounters would flourish, and the feeling of a neighborhood would develop.

They made another critical decision. They would do no dredging and filling, and they would make the natural beauty of Coon Key an integral part of their design, preserving as much foliage as possible and keeping the bird rookery at the southeast edge of the island. “We felt it would provide an interesting contrast to have a manmade tower in the middle of a natural area,” Smith says. “And we also knew we needed the community behind us.”

He credits longtime city manager Ken Thompson for instantly understanding what an asset the project could be for little Sarasota, and after extensive public meetings and outreach—including to environmental groups—Plymouth Harbor won public support and all the necessary approvals.

(Smith says Sarasota had “good, even visionary government” in those days, championing projects from Marina Jack and the acquisition of South Lido Key to the Van Wezel Performing Arts Hall; and he wonders if in today’s contentious climate, when leaders retreat from even a little controversy, anything as bold and new as Plymouth Harbor could be built.)

Plymouth Harbor’s $4 million building permit was the largest in Sarasota history; and it was the most complicated construction project the city had ever seen, the first to require a construction crane. Subcontractors came from all over the state, and the site teemed with activity.

And as Smith climbed up to each new floor as the building rose, it was clear just what a magnificent site it enjoyed, with gorgeous views of sky, shifting clouds and aquamarine water dotted with sailboats and fringed by green mangroves.

The building was completed in 16 months, an extraordinarily short period of time. It was also extremely economical. The cost per square foot came to $10.75. The condo building across Ringling Boulevard, built the year before and an ordinary three-story barracks-type structure, cost $14 per square foot.

At 25 stories, Plymouth Harbor was Sarasota’s tallest building when it opened and is still our tallest structure today.

Image: Courtesy Frank Folsom Smith

Smith stresses that Plymouth Harbor was a collaborative effort, the creation of a talented team of architects, designers and builders, along with MacNeil and the board. But for him, it was also a singular obsession.

For three years, Smith says, “I ate, slept and dreamed Plymouth Harbor, revising ideas and details in my head, waking up to obsess about it, and going on and on about it at family meals and social gatherings.” A favorite family story shows just how true that was. When a kindergarten teacher asked Smith’s son Billy about his father, the little boy replied, “My father is big and tall, and his name is Plymouth Harbor.”

Retirees from all over the country flocked to the new community, which offered amenities from fine dining and a theater/lecture hall to gardens that residents could plant and cultivate. But what convinced Smith and MacNeil that they had succeeded in creating a place where people could live happily during their later years was something that happened a few years later. As is common in senior communities, Plymouth Harbor residents purchase life estates in their apartments, with the price based on actuarial tables that predict how long they are likely to live. But in the 1970s, Plymouth Harbor began to lose money. The problem? “Our residents were living longer than anyone had predicted!” Smith says.

Management restructured the pricing, and today Plymouth Harbor continues to enjoy financial stability—and a long waiting list.

“I grew up during the Plymouth Harbor process,” Smith says. “My career and my identity were formed. It gave me the courage to take on anything—new ways to build, new ideas about communities and urbanism and the way people lived.”

But the project was not without its emotional cost. In 1991, after the building won the Test of Time Award, an article announcing the award appeared in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

The next morning, architect Schneider, who had been part of Smith’s team, appeared in the office of Joan Altabe, the newspaper’s arts and architecture writer. Schneider was furious. He claimed that the most noteworthy features—the high-rise tower and the “colonies”—were his ideas, conceived one weekend in the office while Smith was playing golf.

Altabe believed him. She wrote a scathing three-page article in the Sunday section damning Smith’s reputation and portraying him as usurper and intellectual thief.

The article showed a surprising lack of understanding about how buildings are designed, and other architects jumped to Smith’s defense. A building’s design is a team effort, they explained. Ideas came from everywhere. And Schneider had been given appropriate credit—as “associate architect”—every step of the way. But as to the central point—the tower and the colonies—everyone associated with the project gave credit to the special synergy that existed between Smith and MacNeil.

Eventually, in an official hearing, the AIA ruled that Schneider’s accusations were without merit and Smith had done nothing wrong. But the story hurt Smith’s career and reputation. Though the editor and publisher of the paper later apologized, they never printed a retraction.

For most people, though, that’s long forgotten.

Plymouth Harbor went on to develop a life of its own, becoming one of the most prestigious retirement centers in the country. It brought the city national attention for its quality of life, environmental beauty and architecture. It has attracted accomplished retirees who remain active and involved as they age, and they’ve become an essential part of the Sarasota social fabric.

A U.S. senator could—and did—feel right at home there. An old movie star used to fly down to visit a former lover. The former head of Dow Jones fielded questions about the markets at dinner seminars with his neighbors.

The colonies give every resident a sense of belonging; the site gives them some of the best views in the world; and Smith’s crisp, elegant design gives the place something a retirement center never had before—unabashed glamour.

Opening photo by Chris Lake