Sarasota's Last Lustron Home Goes on the Market

Sarasota is world-famous for its midcentury architecture, and you can hardly pick up a visitors’ brochure without seeing reference to the famous Sarasota School of Architecture—that group of young architects back in the 1950s and ’60s who created ultra-modern houses of glass and straight lines that now take up page after page in the history books.

But let’s face it: The real story of mid-century architecture in Sarasota is not the one-of-a-kind jewel boxes for rich and sophisticated connoisseurs, but rather the everyday homes that everyday people lived in. You can still find them all over town. Some are plunked down at random. Others are part of subdivisions from the era, like Kensington Park and Bayshore Gardens—tract homes, a little rundown and often remodeled out of recognition, but still going strong.

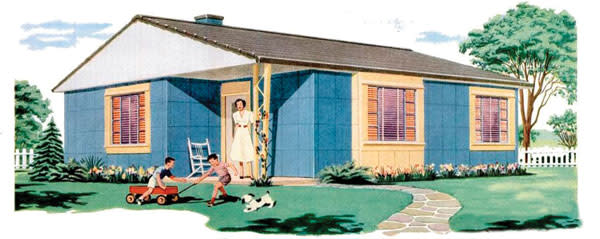

And then there are the Lustron houses. We used to have three. Now we’re down to our very last one. Lustron homes were one of the great architectural experiments of post-World War II America. They were all-metal homes built in a factory in Ohio, then shipped by truck to your own lot, where they were assembled by a local contractor. They had 3,000 pieces, weighed about 12 tons, and took about two weeks to put together. They came in a variety of colors: pink, tan, yellow, aqua, blue, green or gray.

When I say they were metal, I mean they were all metal. The structure had steel framing, steel interior and exterior walls, steel roof trusses, and steel roof tiles. The exterior walls had a porcelain enamel coating baked onto the steel, just like the old White Castle hamburger restaurants. The big selling point was zero maintenance. They never needed painting and to clean them you just hosed them down or used a midcentury version of a Swiffer. They were also fireproof. Just about the only drawback was rust, particularly when the porcelain enamel got chipped.

Lustrons were touted as the solution to the housing shortage that occurred with millions of GIs returning home after the war. Not many homes had been built during the Depression, and virtually none during the period from 1940 to 1945. At the same time, there was a quantum leap in technology. The war had provided lessons in mass production and new materials, and America became the world’s undisputed leader in quality manufacturing. In fact, all the Lustrons were built in what had previously been a military aircraft factory.

But if they had a radical mindset, the Lustrons still had a comforting, old-fashioned feeling. These were not the glass boxes with flat roofs that characterized the Sarasota School. Squint a little and you see a time-honored traditional Cape Cod cottage.

As far as I can tell, Sarasota had three Lustrons. They were all in Southside Village. I remember distinctly that one was at the corner of Datura and Osprey. It was torn down about 10 years ago. Another was rumored to have been on Hillview, but it seems to have been lost to history. That leaves the one at 1956 Rose St., which not only is still intact after all these years, but is for sale.

It belongs to the Hudson family. Dr. George Hudson is retired now but for years he had his chiropractic office on an adjacent lot. He bought the Lustron in the 1970s and used it as a rental. One of his sons lived there for a time as a young bachelor and the kids still look back fondly on parties in the backyard. Another son, Greg, is now a realtor for Coldwell Banker, and he is handling the sale of the home.

It’s a Westchester model, the most popular, in “surf blue.” There are two bedrooms, living room, dining area, kitchen, bath and a good-sized utility room. The overall size is 982 square feet.

What’s it like inside? Everything really is metal. Tap the walls. They’ve been painted with latex paint, but one tap and you can tell. (By the way, you hang pictures with a magnet.) The dining area has a built-in hutch/pass-through/buffet that’s a great example of late 1940s design. Likewise, the closets, built-ins and vanities. In the living room is a recessed mirror set off by shelves that is likewise perfect.

The rooms are relatively large, made even larger-seeming by all the built-ins and careful planning. All interior doors are pocket doors. The bathroom is not really original; it has one of those vanities from Home Depot that you buy when you’re remodeling a cheap rental. The original kitchen is about half there; the appliances are gone but the cabinets remain, some a little dented. It’s also missing one unusual feature the house came with: a Thor washer, a strange combination dishwasher and clothes washer that not only never caught on, but repulsed people. Sometimes modern technology goes off on the wrong track.

In fact, that’s sort of what happened with the Lustrons. They were projected to be one-third cheaper than a conventional house, but costs kept rising until they were priced over $10,000. Carpenters’ unions refused to work on them, and a proper distribution system was never worked out. Building codes were a problem. Even though enormous crowds turned up to tour them, only about 2,500 were ever built; and the company went bankrupt in 1950, after only two years of operation.

Today they’re considered the ultimate ’50s collectible. There are all sorts of preservation societies and tracking registers and fan clubs. One Lustron is in a museum in Ohio and another was exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art. I myself find them fascinating and almost bought the last one in Bradenton. It’s the yellow Westchester model at the corner of 22nd Street West and 15th Avenue West. I made an offer: $119,000. The seller professed to be highly insulted and negotiations fell apart. I’ve often wondered if I missed a bullet or the best opportunity of my life.

The Hudsons are selling their Lustron for $389,000. This is based on the lot value; it is assumed the new owners will tear the house down, as it’s a prime lot in one of the hottest neighborhoods in town.

But the Hudsons are certainly open to a deal. If someone wants to move the Lustron—granted, some of it is rough but in my judgment it’s eminently restorable—make an offer. There’s even a booklet you can order that tells you exactly how to dismantle one and reassemble it. It should take 1,040 hours and you’ll need a crew of two to four men. You’ll also need a lot to put it on, of course, but you’ll end up with a real classic—maybe the classic of mid-century American architecture.