Selby Gardens’ Upcoming Exhibition Brings to Life the Vivid Designs of Louis Comfort Tiffany

Daffodil lamp, Tiffany Studios, early 1900s.

Occasionally, the artists selected for Marie Selby Botanical Gardens’ Goldstein Exhibitions, which focus on nature, can feel surprising—like Andy Warhol or Salvador Dalí, for example. But the 2023 choice for the exhibition feels like a no-brainer: artist and designer Louis Comfort Tiffany, whose stained-glass windows and lamps often feature botanical elements and colors derived from the natural world.

The exhibit, Tiffany: The Pursuit of Beauty in Nature, opens Sunday, Feb. 12, and is on display through Sunday, June 25. As always in the Goldstein series, not only will works by the artist be on view in Selby’s Museum of Botany and the Arts, but the gardens’ horticultural team will take inspiration from Tiffany’s work to create living displays, with hundreds of bromeliads forming floral mosaics of “stained glass” and blooming butterfly plants brightening the outdoor vignettes, as well as orchids, gesneriads and more filling the Tropical Conservatory.

Lotus, Pagoda lamp; Tiffany Studios, early 1900s.

David Berry, the vice president of visitor engagement and chief museum curator at Selby, says this is the first time Tiffany’s creations will be on display in a botanical garden. “We’re always looking to highlight the art of artists who are well known, but to present it in a new, different context,” Berry says. “When you look at the forms in Tiffany’s works, his vases, windows and lampshades, filled with flora and fauna, it seems like the perfect collection.”

The Tiffany pieces come from a private source who has chosen to remain anonymous. The range of shapes and imagery is wide, from the delicate leaves of a flower to luxurious lily pads to vibrant dragonflies and daffodils. Viewers will appreciate not only the beauty of the works, but the technical skills that brought them to life—skills shared by Tiffany and the many artisans who worked in his studio, including a number of women. That was unusual for his era, which began in the late 19th century.

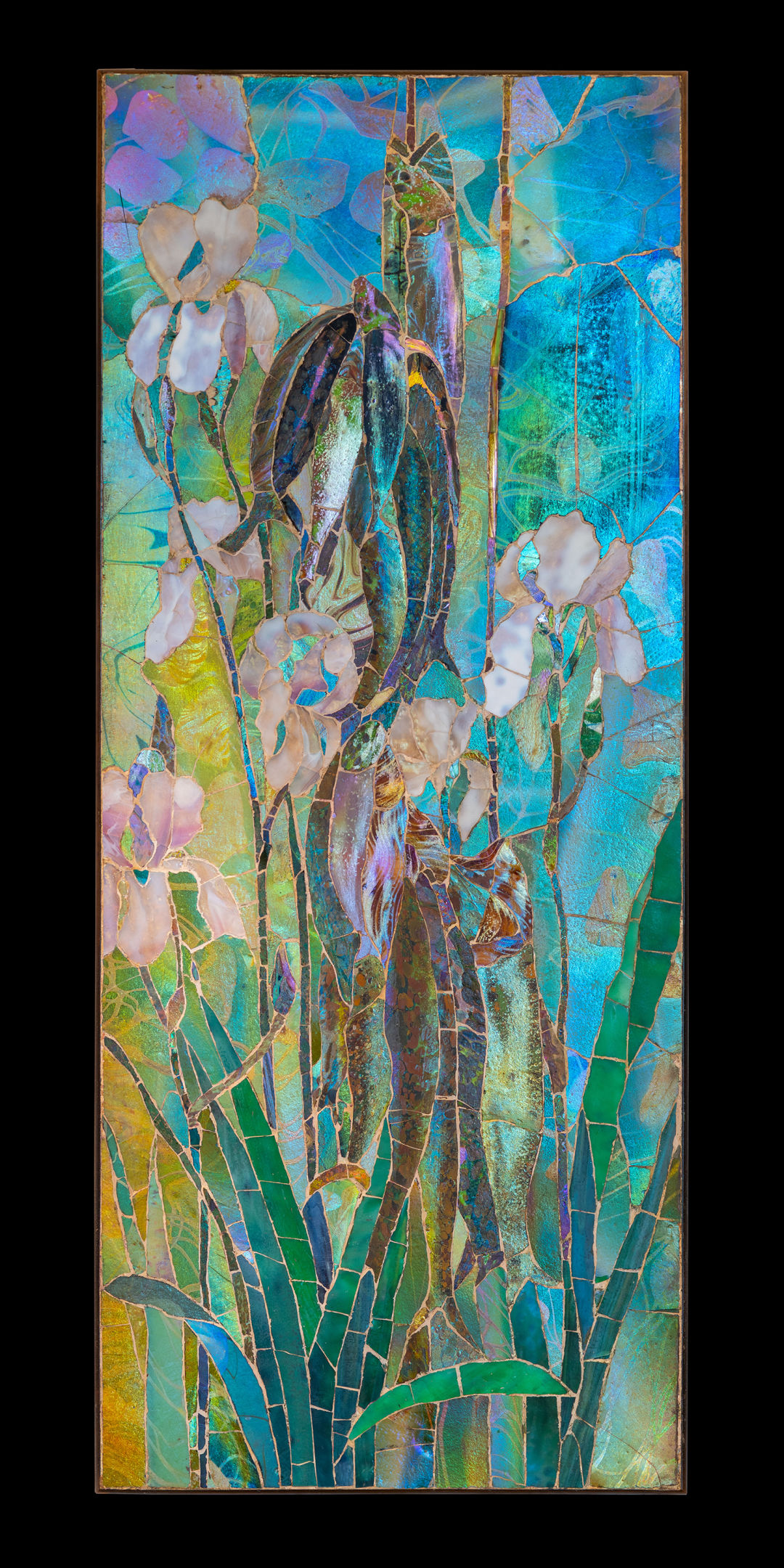

Fish and irises mosaic, Tiffany Studios, circa 1906.

“We are going to try to highlight the works of other artisans, especially the female artisans who produced some of these iconic images,” Berry says. “Tiffany employed 40 to 50 female craftspeople, at equal pay and with managerial respon- sibilities, recognizing their skills and talents.”

One woman who certainly appreciates Tiffany’s legacy is Nadia Watts, his great-great-granddaughter, who will speak about her famed ancestor and his career on Tuesday, Feb. 14, at Selby’s downtown campus. Watts currently runs her own interior design firm in Denver and says she’s not the only Tiffany descendant who has worked in the arts. Her mother is an arts educator, and various uncles, aunts and cousins have also been involved in creative endeavors.

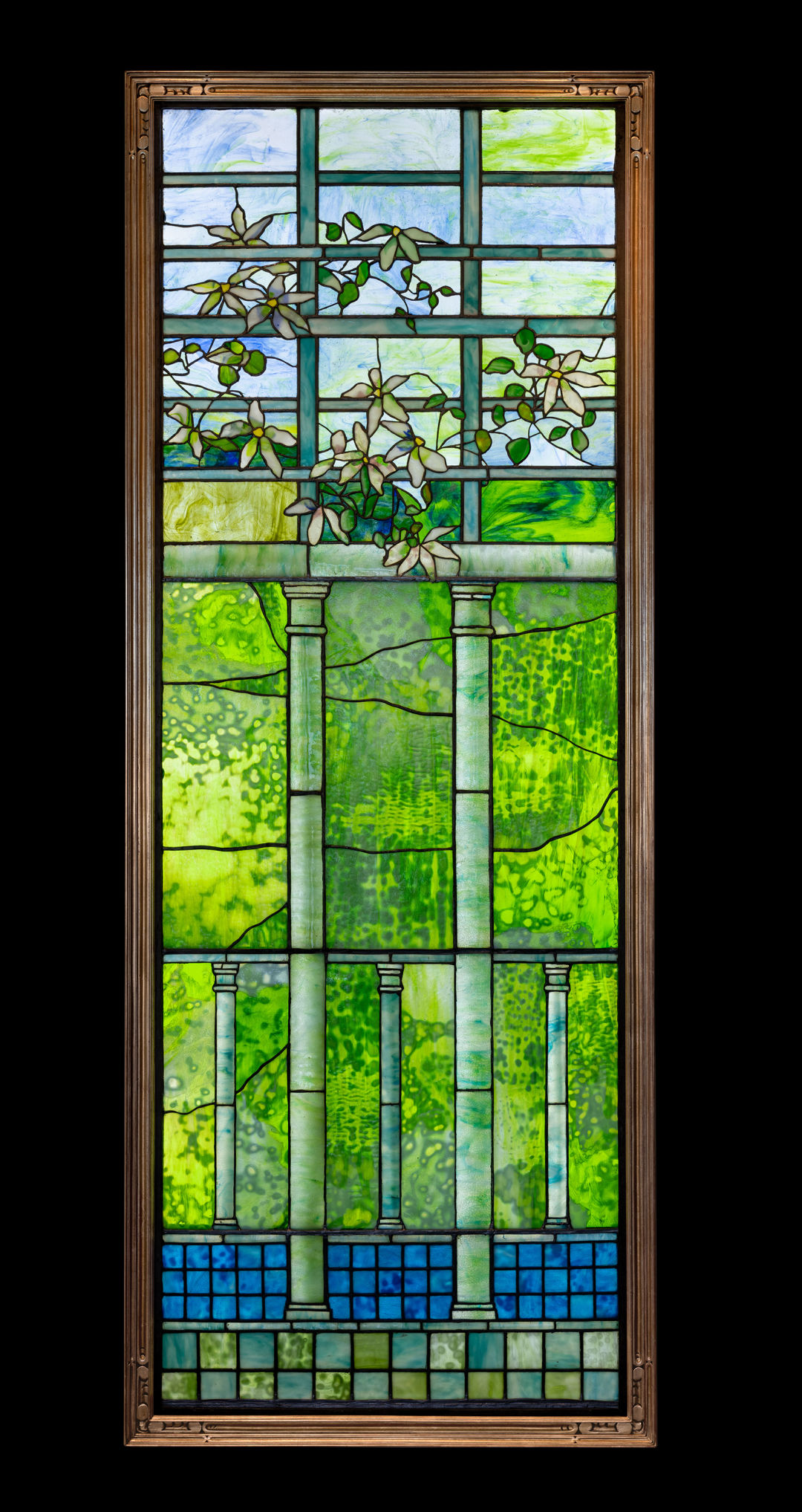

Clematis vine window, Tiffany Studios, circa 1906.

One of Watts’ first memories of Tiffany’s work centered on an exhibit at the Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., when Watts was about 6 years old. “There was a black-tie opening, for which I was too young,” Watts says, “but my mother took me later and we walked through the museum. Seeing the beauty of the glass, the landscapes in the windows, is a moment that stands out. As a child, you know it’s important, but you don’t know all the details.”

Eventually, Watts interned with an interior designer, finished her B.A. and worked for a time as an assistant at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. More recently, through the Kravet home furnishings firm, she unveiled her own line of fabrics, the Nadia Watts Gem Collection, inspired by her great-great-grandfather’s eye for colors and texture.

According to a book produced by Watts’ mother, the family “inherited the gift of color” from Louis. “His legacy is color, how color is used and looking at something in a different way, embracing that and trying it,” Watts says. “He had an eye that wasn’t just an artist’s eye, but an architect’s eye, as well.”