The Strange, Spectacular, Sad Story of The Ringling Bros.' Elephant Polka

Sarasota is one of those special cities whose name is instantly identifiable with an art form. Just as Los Angeles is home to the movies and New York is home to Broadway, Sarasota is home to the circus. During the Big Top’s heyday, our town was full of people creating art.

Some were world-famous stars, like the Wallendas, animal trainer Frank Buck, and clowns like Lou Jacobs and Emmett Kelly. Others—thousands, in fact—were here to provide them a glittering support system—costumes, sets, music and lighting. The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus winter headquarters bustled with activity, rather like a Hollywood studio. There was so much to see, rehearsals and wild animals, that it was the largest tourist attraction in the state.

The defining factor of the art created in Sarasota back in those days was its unabashedly lowbrow nature. The circus defined the term lowbrow. It was broad, overly bright, noisy, had an earthy smell and was aimed at the masses. Anybody, even a 3-year-old, could understand it just by looking it.

It was the polar opposite of that other kind of art, the highbrow. That’s the world of intellectual art, where moral dilemmas are examined and innovative techniques are embraced. High art often drew inspiration from the circus (Picasso had a circus period), but for the circus to flirt with highbrow art seemed like a disaster waiting to happen.

But it did happen, just once, with spectacular results.

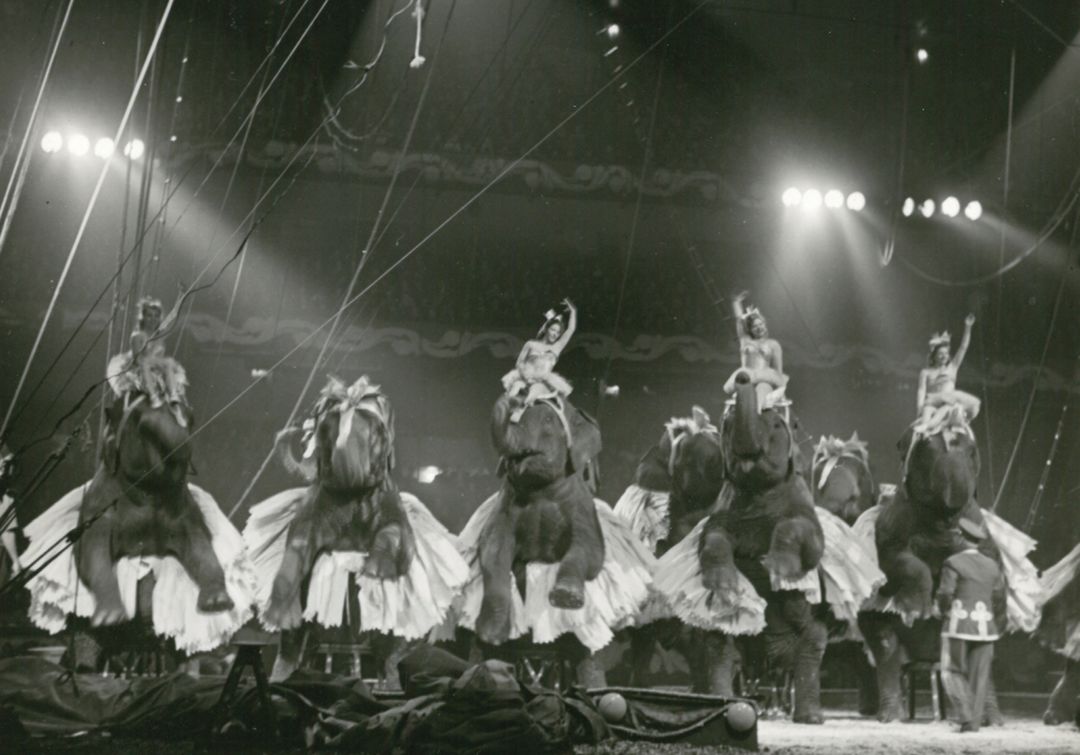

Elephants and dancers in the ring

Image: The Ringling

Our story begins at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. John Ringling North, who inherited control of the circus from his uncle, John Ringling, just two years earlier, had put together an equestrian show for the fair, with exhibition and acrobatic riding and a Wild West show, presented five times a day. It was a look backward to the sort of thing the circus had been doing for decades, and it was a big flop.

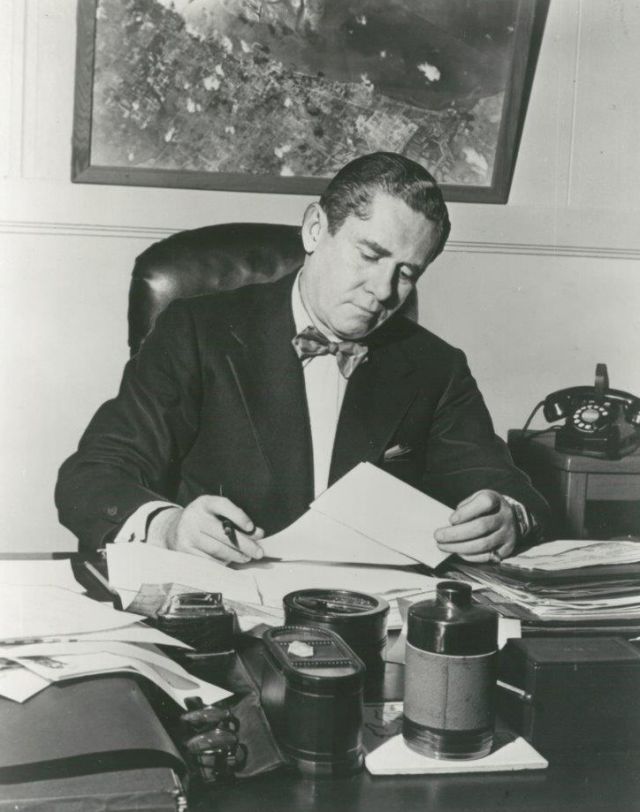

John Ringling North

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

The big hit of the fair was the exact opposite—a look into the future. At the General Motors pavilion, the Futurama exhibit always had a three-hour line. In an enormous streamlined building, you would sit in a plush armchair and be whisked through an 18-minute ride over and around the “world of tomorrow,” a vast miniature creation of what the world would look like in 1960. Perfectly composed cities and picturesque countryside were connected by a graceful system of throughways. The cars on the throughways actually moved. The city of the future contained wonders only dreamt of: landing pads for helicopters, a sports stadium with a retractable roof, and even a revolving restaurant set atop a skyscraper. Over half a million tiny buildings had been created. People were astonished.

So was North. He found out all he could about its designer, a man named Norman Bel Geddes. (Norman added the Bel to make himself seem more exotic. And, yes, his daughter was actress Barbara Bel Geddes.) One of the great design geniuses of the last century, Bel Geddes pretty much invented the field of industrial design. He could improve anything, usually by stripping it down to its essence and then streamlining it.

He designed everything—ships, planes, cars, radios, furniture, stage sets. He was both an artist and a social thinker. He told us we could create a world that was clean, efficient and harmonious. As one critic said, “He was a missionary preaching the gospel of modernism.”

North arranged to meet with Bel Geddes and discovered something else. The designer was just as much of a showman as he was.

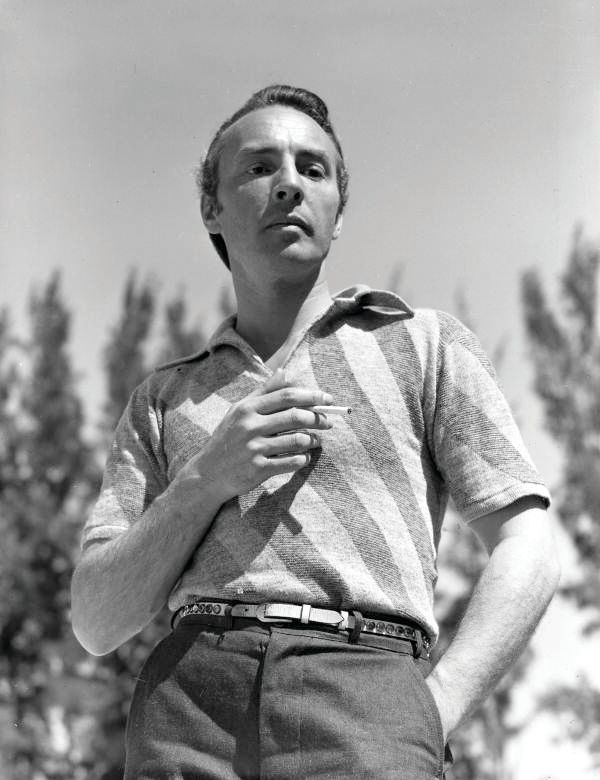

Norman Bel Geddes

Image: Library of Congress

They made a deal. Bel Geddes would be given a free hand to redesign—indeed, rethink—the circus. Up until now it had been a series of unrelated acts, with a sideshow and menagerie attached. Bel Geddes turned it into a cohesive experience, united by color, design, lighting and costumes. Each year had a different theme—for example, Mother Goose in 1941—and everything flowed from that unifying principle. The entire 1941 show was now a story being told to Old King Cole.

The Big Top was now blue; the menagerie tent red. Posters were redesigned in an avant-garde style by the leading poster artists of the day. Sideshow banners were repainted in a modernistic style, along with a jungle-themed menagerie. There were new concession stands. Aerial ballets featuring scores of showgirls were added. Bel Geddes built a new home—air conditioned—for Gargantua, the star gorilla. He even changed the very sawdust. Now it was colored pink in rings one and three, with gleaming white in the center ring and blue in the surrounding hippodrome track.

Circus purists were appalled. But the public loved it. The 1941 season, produced as war engulfed Europe, was the most successful ever. North even talked Bel Geddes into redesigning the bar at the John Ringling Hotel in Sarasota. It became a masterpiece of jazzy midcentury design, with witty murals by Anton Refregier.

When production for the 1942 season began, North called a meeting at his mother’s home on Bird Key. He had an idea. The circus elephants were one of the biggest draws, and all 50 of them performed in parades and production numbers. What if they performed their own ballet, to original music?

As they kicked around ideas, Miles White, the new costume designer hired by Bel Geddes, came up with the perfect person to pull it off: George Balanchine.

Elephant trainer Walter McClain with elephants.

Image: Public Domain

Balanchine has gone down in history as the most important choreographer of the 20th century. He was synonymous with the aesthetic rigor of high art. Born in Russia in 1904, he got his early training at the Imperial Ballet School, but like many Russian dancers, he defected to the West. In Paris in the 1920s, he made his reputation with a series of successes, working with such composers as Stravinsky, Debussy and Ravel. Many of his pieces for the Ballets Russes had sets and costumes by artists like Matisse and Picasso.

George Balanchine

Image: Public Domain

His instantly recognizable style was known as “neoclassical.” It was pure dance, stripped down to the essentials. To him it was all about the choreography. Telling a story, the narrative of the dance, did not interest him. He was also famous for his prima ballerinas and married four of them. Their appearance was crucial to him, particularly their weight, and many of his dancers had scary bulimia and anorexia tales to tell.

But Balanchine was adventurous and had an open mind. One of his favorite dancers was Ginger Rogers, and he was one of the first to incorporate motifs of Black dance into his work. So when he got a call from John North asking if he was interested in choreographing a ballet for 50 elephants, he immediately said yes.

His new corps de ballet actually had a varying number of elephants, and some of the ballerinas were bulls, as male elephants are called. They were very well trained and could move in time to music, if it was simple enough. There was a prima ballerina, the famous Modoc. Actually, the circus at that time had three Modocs: Big Modoc, Little Modoc and Wallace Modoc. But Big Modoc was the star, a celebrated performer in her own right, featured on the posters, and definitely not anorexic.

Balanchine’s immediate problem was the music. The circus, of course, had plenty of music. Circus tunes are perhaps the most recognizable in the world. And the Ringling band, led by the famous Merle Evans, was a unique collection of instruments, including a Hammond organ.

But Balanchine recognized the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity in front of him. He needed a composer with a lot of nerve, and his mind went immediately to his old partner, Igor Stravinsky. They had worked together many times before, and their collaborations were among the most storied and successful in the world of music. There was no one who embodied “high art” more than Stravinsky.

In 1941 Stravinsky was living in Los Angeles, a refugee from the war in Europe. It was a busy, nerve-wracking time for him. His brother and his niece had just died. He was trying to complete the Danses Concertantes and worrying about his future. Then he got the phone call from his old friend Balanchine.

“I wonder if you would like to do a little ballet with me,” Balanchine began.

“For whom?”

“Some elephants.”

“How old?”

“Very young.”

“All right. If they are very young elephants, I will do it.”

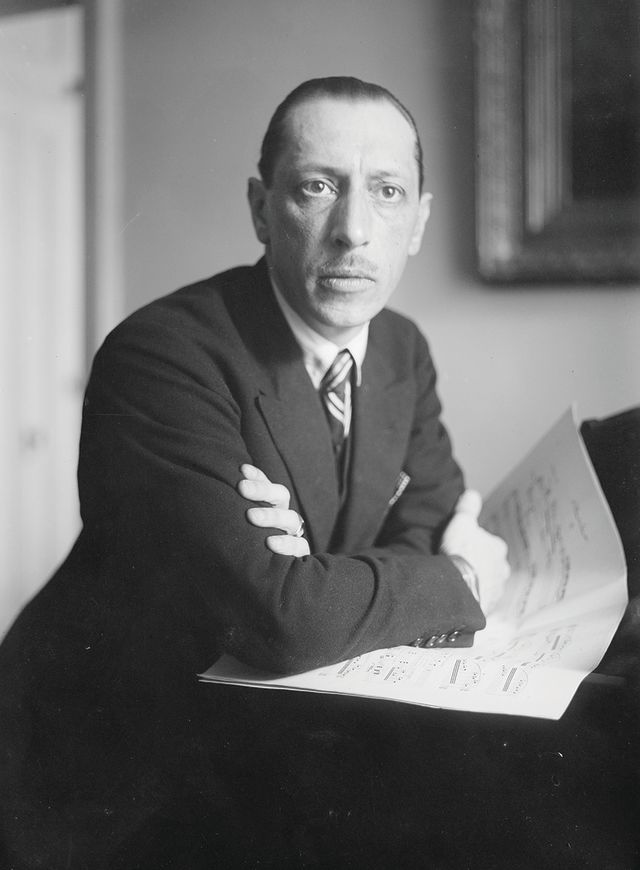

Igor Stravinsky

Image: Library of Congress

And so the genius who woke up the world to modernism with his score for the ballet The Rite of Spring set to work. He made no bones about why he accepted the commission. The fee was large, and he could dash it off in no time.

The completed piece was just under four minutes long and was dubbed the Circus Polka. Only parts of it are in polka rhythm; the meter changes frequently and it uses musical phrases from Schubert’s Marche Militaire. The overall effect is light, happy, circus-like, and perhaps a little complicated.

Back in Sarasota, at the winter headquarters out on Beneva Road, Balanchine was working with his dancers, both human and elephantine. The beasts were having trouble following the rhythm changes. More than once their nerves overtook them and they would bolt. Balanchine and trainer Walter McClain would have to chase after them.

Costumes were designed by Miles White and Bel Geddes, pink tutus for all of them, including the bulls, plus elaborate headdresses and earrings. The circus band did its best with the Stravinsky orchestrations, but there was a feeling of unease as showtime drew closer. It was all so bizarre. Was it too highbrow? Would it work?

They needn’t have worried. Opening night, April 9, 1942, at Madison Square Garden, was a triumph. Vera Zorina, Balanchine’s wife at the time, took the role as lead dancer for the gala charity premiere. Modoc carried the ballerina out in her trunk and delicately placed her in the middle of the center ring. Then the rest of the elephants entered, each with a ballerina, and encircled the arena. Here’s what The New York Times wrote the next morning:

“They came into the ring in artificial blue-lighted dusk, first the little pink dancers, then the great beasts. The little dancers pirouetted into the three rings and the elephant herds gravely swayed and nodded rhythmically… The arc of the sway widened and the stomping picked up with the music. In the center ring, Modoc the Elephant danced with amazing grace and in time with the tune, closing in perfect cadence with the crashing finale.”

The Circus Polka was a triumph. As one historian put it, “The only stampede was to the box office.” Thousands attended the 42 performances. Millions more saw it as it toured the country. Yet after the 1942 season it was never performed again. North’s Ringling cousins began to fight for more control of the programming and the content. The circus became less adventurous. The glorious attempt to blend high and low culture came to an end.

But the Circus Polka took on a life of its own. Stravinsky (in an odd twist of fate, his son Soulima, also a composer, retired to Siesta Key and died in a nursing home on Tuttle Avenue in 1994) reorchestrated the piece for a symphony orchestra, and today it is in the repertoire of companies all over the world. Jerome Robbins, Balanchine’s great rival for the title of most influential choreographer, created his own version. He replaced the elephants with little girls in pink tutus and had a ringmaster direct them. Mikhail Baryshnikov played the role several times and reviewers called it “cute in the best possible way.”

Six-year-old girls instead of elephants. Maybe it’s better that way. It has become the fashion today to re-examine the past and make moral judgments about it. From this point of view, the Circus Polka changes from a nice little story about a circus performance and turns into a tale of abuse and exploitation.

Ringling's elephants performing the Circus Polka

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Elephants are sensitive animals, social in nature, who communicate, raise families, mourn their dead, empathize and mentor their young. The ones that worked for Ringling were forced into a life very different from what nature intended. Now they were separated from their mothers shortly after birth and trained, with bull hooks, whippings and electric shock, to perform tricks. They lived in cages, were often chained and forced to stand all day on concrete. It must have been a very unhappy existence.

In the 1970s, the emerging animal rights movement took aim at Ringling Bros. and waged a decades-long campaign that not only ended the elephants’ participation in the circus but eventually the circus as well. In a sort of “#metoo” coda to the story, the elephants finally got the circus canceled. For good. Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey officially closed down on May 21, 2017, after 133 years in business.

One wonders what the elephants thought about all this. When they retired, which they did when they got too old to work, they were sent to an animal preserve to live out their days. People who worked there reported that sometimes they would see members of the herd standing there, finally free from their cages and bull hooks, with their heads swaying and their feet moving, doing the Circus Polka.