Sarasota Film Festival: Making Montgomery Clift

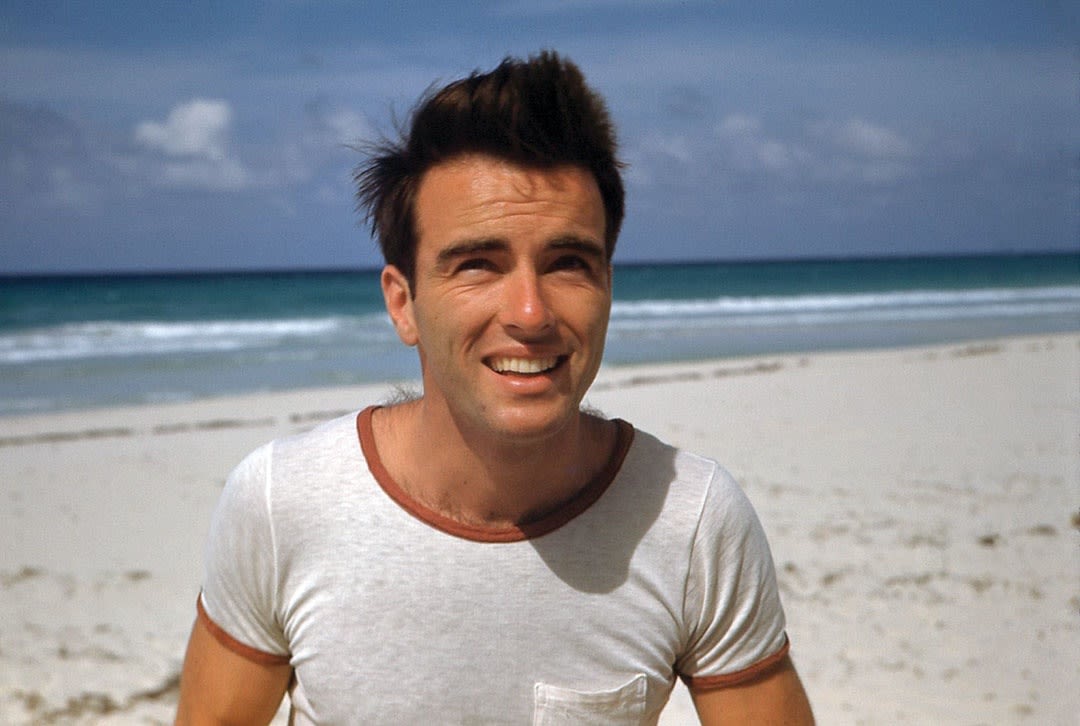

The young and handsome Montgomery Clift.

It’s often fun to look for Sarasota connections to the films shown during the Sarasota Film Festival. Of course there are a number made by Sarasota-based film makers, or about Sarasota subjects. Admittedly the connection between the documentary Making Montgomery Clift, which I saw yesterday, is more tenuous: The actor appeared while still a youngster in shows at the Players Theatre, now the Players Centre for the Performing Arts.

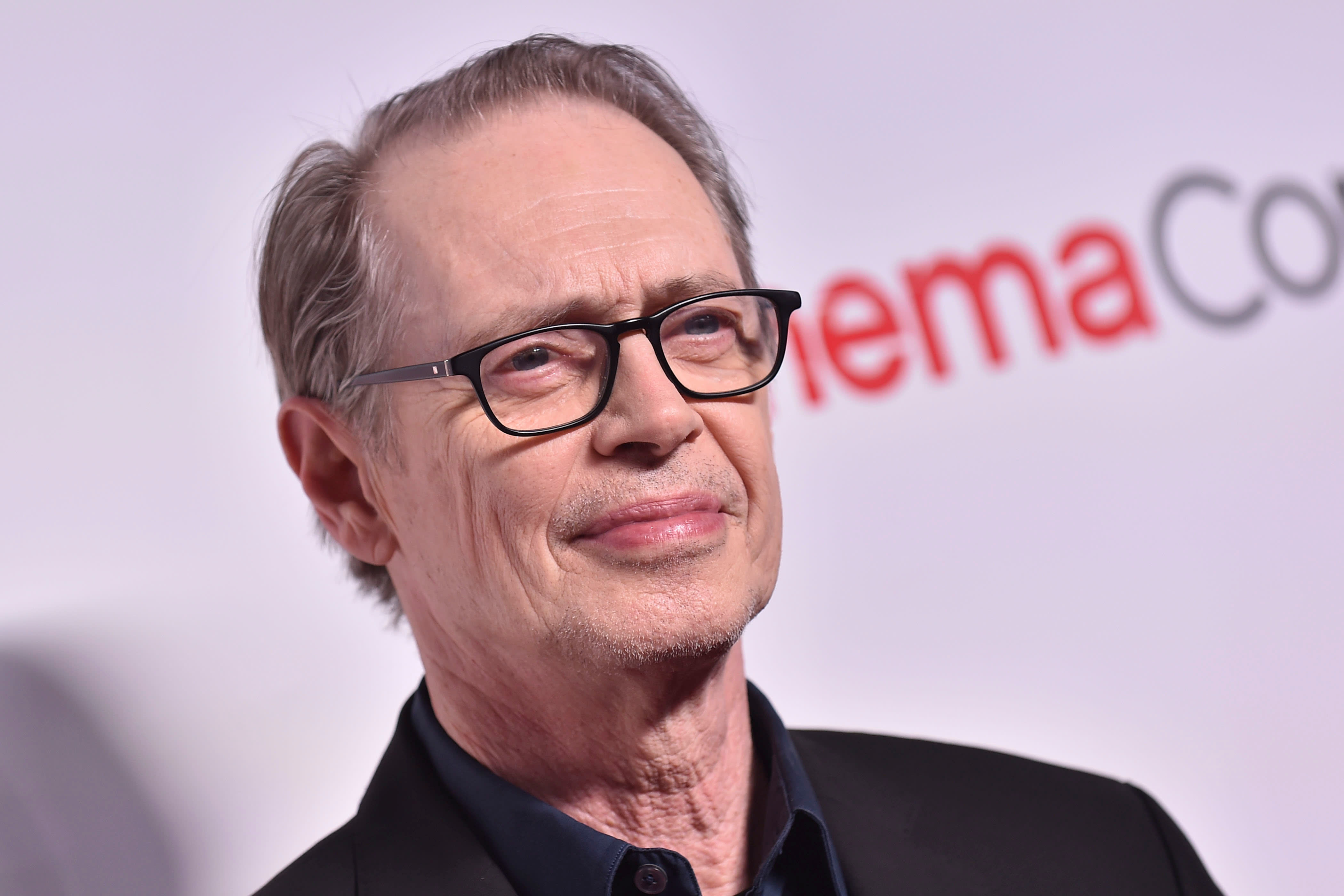

His time in Sarasota, however brief it may have been, is not mentioned in the film, which was directed by his nephew Robert with Hillary Demmon. There are plenty of images of an unbelievably handsome young Monty, though, along with some convincing evidence that the image many of us have of Clift—a soul tortured to the point of alcoholism, drug use and a “slow suicide” by his closeted sexuality—may have been a misrepresentation by the media and his biographers.

Robert Clift never met his uncle, who died in 1966, but his father, Brooks, was Monty’s older brother, and he worked diligently for years to protect his memory. The film at times is almost as much about Brooks as his more famous brother, as it shows us the piles and piles of memorabilia Brooks collected from Monty’s career, and makes extensive use of the audio recordings Brooks apparently made of routine telephone conversations (a habit he may have acquired during time in the intelligence service).

While those of a younger generation may not be that familiar with Montgomery Clift’s work, he appeared in a number of classics in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, after having delayed entry into the moviemaking world (he did extensive theater work beforehand) because he didn’t want to sign a long-term contract, preferring to have more say in the roles he played. A Place in the Sun, The Young Lions, Red River, Raintree County, The Misfits and Judgment at Nuremberg (a very brief role here, but one with great impact) are just a few of the films he appeared in. The documentary makes a case that his creative input into many of the movies was deeper than just starring before the camera; marked-up scripts and transcripts of conversations show that Clift was also a writer-editor, and to some extent directed himself, too.

But in later years the work often seems to have gotten lost in the media coverage that found in his life a tragedy, because of his bisexuality (he had relationships with both men and women, but men, like the late fellow actor Jack Larson, who’s interviewed in the film, were more the norm), the car accident in 1956 that changed his face, and a lawsuit involving director John Huston and the movie Freud. Those closest to him, however, remember a sense of humor and his dedication to doing the best work he could, while decrying the pop psychoanalysis that dogged him.

For film mavens, Making Montgomery Clift is worth seeing, so be on the lookout; it should pop up on a streaming service sometime soon. Meanwhile, for more upcoming movies here this week, visit sarasotafilmfestival.com.