What Does Climate Change Mean for Sarasota?

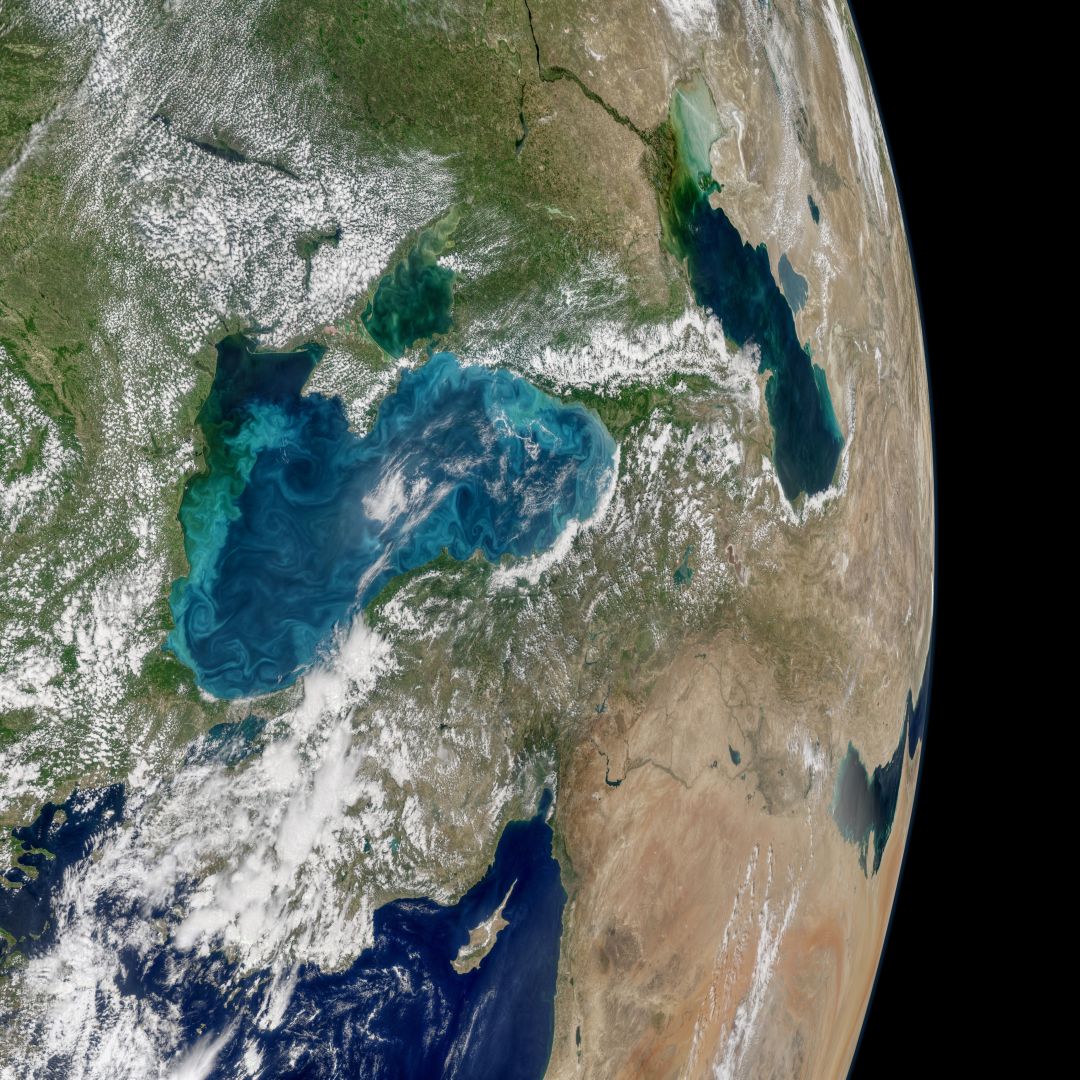

A view of Earth from space.

On Monday, the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a landmark climate report predicting that the planet will experience major climate change-related crises as early as 2040 if the earth's global average temperature rises 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-Industrial Revolution temperatures. (For reference, the planet's current temperature is already 1 degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels). The report's authors warn that the effects of that level of global warming would be devastating and include mass extinction events, the decimation of coral reefs, food shortages, droughts and super storms.

Scientists have long known the hazardous effects that fossil fuels have on the planet; an 18-month, multi-part investigation published by The New York Times in August cites an EPA report released in 1977 that stated, "The continued use of fossil fuels might, within two or three decades, bring about ‘significant and damaging’ changes to the global atmosphere.” The Times story also suggests that between 1979 and 1989 we could have solved the climate change problem, and that world leaders came within a hair's breadth of signing an agreement that would have significantly reduced carbon emissions on a global scale. That didn't happen. Now, 30 years later, the world faces unprecedented climate-related challenges. Just look to Hurricane Michael, which experts say likely grew so powerful so quickly in part because of warm Gulf waters, for evidence of this.

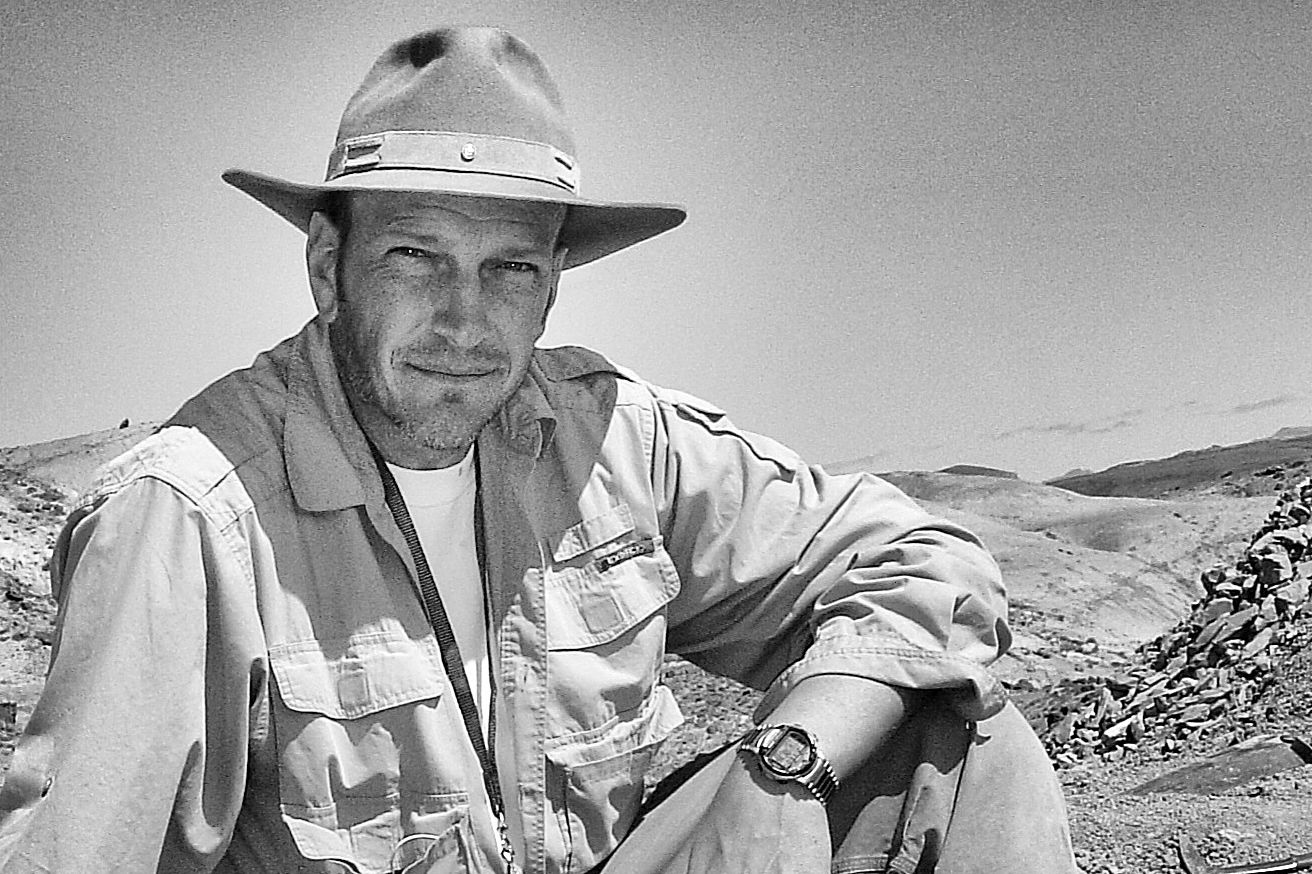

The outlook certainly seems dire—so what can we do? We asked Dr. Terry Root, a senior fellow emerita at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment at Stanford University and a Sarasota resident since 2015. Root, a Princeton graduate who got her start studying climate change based on birds' migratory patterns, was a co-author of the third IPCC assessment in 2007, which shared a Nobel Prize with former vice president Al Gore. She's on the board of the national Audubon Society and has dedicated her life to studying how plants and animals are affected by climate change. Here's what she had to say about the latest IPCC report—and her advice for mitigating climate change on an individual and national scale.

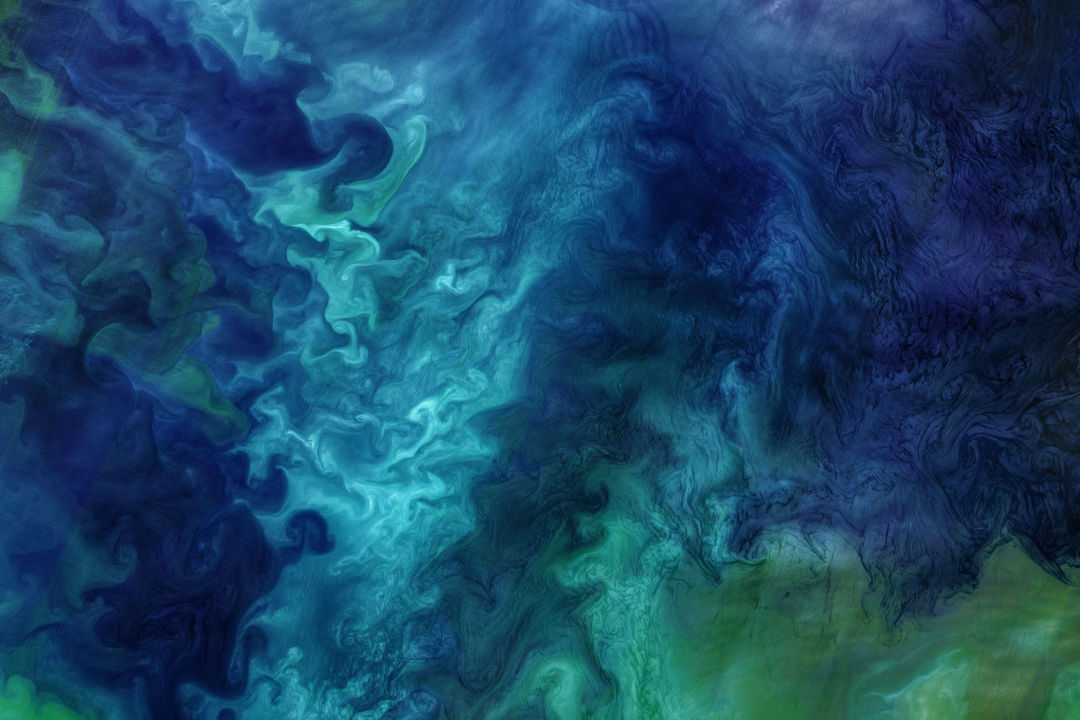

Phytoplankton blooms in the Chukchi Sea, off the coast of Alaska.

Your love of birds was the catalyst for your career in climate change. How did that start?

When I was 14 years old and my mother was fixing Thanksgiving dinner, she told me to get out of her way because our kitchen was too small, and that I should go outside to look at birds. So I did, and I identified two all by myself. That was the start of my love for birds.

How did you get involved with the IPCC?

I was asked to review the IPCC's second assessment report, which I did, and I told them, "This is easy to review; there's zero information about wild plants and animals." I knew that had to change. So the IPCC asked me to work on the animal aspect for the third assessment, and I wound up being involved with the organization for 21 years. I worked on the third, fourth and fifth assessment reports.

The 2007 IPCC report team was co-awarded a Nobel Prize with former vice president Al Gore. What were some of the key findings that year?

In 2007, the IPCC determined that if the global average temperature heated up to 2 degrees Celsius [3.6 degrees Fahrenheit] above pre-industrial temperatures, we could lose 400,000 species to extinction. If the earth heated to 4 degrees Celsius [7.2 degrees Fahrenheit] above pre-industrial temperatures, we could lose half the species on the planet. So 2 degrees Celsius became the magic number. Historically, we've found that temperature won't cause the methane that's frozen in the oceans to melt. If the methane melts, the global average temperature could spike 4 to 6 degrees in 25 years. That's because there's so much of it, and because methane is a much stronger greenhouse gas than CO2.

What did the latest report find?

In the report that came out this week, the authors said, "Hey, folks, we're skating so close to melting that frozen methane, let's change the number from 2 degrees Celsius to 1.5 degrees Celsius." It's like we're hitting the guardrail—keeping the global average temperature from heating up is protecting us from absolute catastrophic destruction. The question is, how do you keep temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius when we're already at 1 degree? We have to make some huge changes.

A view of the Everglades from the International Space Station.

Image: NASA

What would that destruction entail?

Massive droughts, intense storms, sea level rise and acidic oceans. Hurricane Michael was huge because the Gulf is so warm, and the Gulf is so warm because the planet is so warm. So we're having storms on steroids, and they're killing not only people, but other species that we need. Scientists are also predicting that sea levels will rise 9 feet by 2100—and that number does not yet take into account the melting of Greenland and Antarctica, because we don't understand why they're melting.

What does this all mean for Florida and Sarasota?

Anna Maria Island, Longboat Key and Siesta Key will be underwater. The new Bay development downtown will be underwater. Politicians say that it's too expensive to reverse climate change or that we can't do anything about it, but that's not the case. The number of jobs we're creating from renewable energies is almost two times as many as those we have for fossil fuels. It's helping the economy, not hurting it. If we take the money that we'd be saving and put it into [creating jobs in renewable energy and] avoiding fossil fuels, it would be a win-win. But if we don't do something, the amount of money it's going to cost to try to avoid future destruction will be astronomical.

How would it affect our wildlife?

We rely so much on fish in this state, and the pH of the ocean is devastating fisheries and oyster farms. For example, young oysters can't glean enough calcium from the water to make the shells they need. Ocean acidification is also affecting bony fish and plankton, and plankton is crucial to feeding other species.

Think about this: About 40 percent of the human population lives along a coastline, and 97 percent of those people get their main source of protein from the oceans. If we're losing fish in the sea, where are the people that live on the coastline going to get that protein? Florida is a great example. We get a lot of protein from the oceans, but everything is migrating north.

I'm super worried about shore birds that nest on our islands, too. With sea level rise, we're also worried about storm surge, and those birds are going to be in trouble. If the seas rise 9 feet, as predicted, the birds are going to run into human habitation, like yards or parking lots. There won't be any place for them to retreat. The other issue is food availability. As the oceans have gotten warmer, species are moving around, and young birds are migrating here at a different time than their food is.

And if we start losing birds like tree swallows and chimney swifts, which are very common, we'll have trouble with flying insects, mosquitoes and spiders—birds act as a natural pest control for those things. I moved here in 2015, and since then the number of chimney swifts has dropped dramatically.

A view of Earth captured by International Space Station commander Alexander Gerst.

Image: ESA/NASA-A.Gerst

What can we do on a personal level?

We have to get our politicians on our side. One of the main things we can do right now is vote. California leads the country in its response to climate change and it's not even ground zero; Florida is ground zero, and we could be an example to the country in showing what we can do to mitigate it. For example, the City of Sarasota is committed to using 100 percent renewable energy city-wide by 2045; if our state government won't do something, at least our city will. But we need a president and a governor who have the political will to take up climate change.

What else?

Start consuming less red meat and dairy. The amount of methane the livestock industry puts into the atmosphere is similar to what the transportation industry puts into it. You don't have to cut out beef and milk entirely; just decrease it. Have a meatless Monday and see how it goes, then after a year or so, add in a meatless Wednesday.

Drive an electric car. There are a lot more being produced. Nissan is coming out with a Leaf that can go more than 200 miles on a single charge, and the car is around $30,000, which is in the realm of possibility for a lot of us.

Combine your trips. Don't drive to Costco, then back home, then to Trader Joe's, then back home. Lump your travels and errands together in a way that makes sense for you. It can make a huge difference.

Try to walk or bike when you can. That's also good for your health!

Insulate your home. If you have a broken window or door, put in an insulated window. We lose a lot of energy through our windows, doors and roofs that aren't insulated well enough.

Turn up your air conditioner by 1 degree. That makes a huge difference, and it's an easy thing to do. And in the winter, turn down your heater by 1 degree and put on a sweater.

Encourage carpooling. If you commute to work, ask your officemates if they wouldn't mind riding together.

Buy high-efficiency appliances. Not only will they ultimately save you money, they'll help save the planet.

What's your response to the idea that our human ingenuity will come up with a solution that will solve climate change-related problems?

There have been many, many studies that say it takes 30 years to go from a great idea to a scalable, working solution. For example, some say that we could use coal to make electricity because of a process called the Allam cycle, which converts fossil fuels into mechanical power. But 30 years of using coal would be devastating for the planet—the global average temperature would go over 2 degrees Celsius in a second. And we don't have 30 years—we have 13.

How will this affect our kids and their kids?

The kind of world our children are going to live in is one we've never experienced. We have no idea how people will react if they don't have enough food and water. Will it be like the Wild West? And is that really what we want? We need to do everything we can to avoid it.

When you think about the future, do you feel hopeful or resigned?

I give talks all the time on climate change, and I have a slide that shows the per capita use of carbon by the world, by the U.S. as a whole and by state. One of the most hopeful slides shows that California's carbon use is very low—and that means we actually know what to do to fix this problem. Now, I realize that California has never met a regulation it didn't love, but right now regulations are what it's going to take.

My late husband, [influential Stanford climatologist Stephen Schneider], used to say, "I've never seen a Republican flood or a Democratic fire." It's not political. This affects all of us. We need to do whatever we can to stop it.