Powerful Landowner Hugh Culverhouse Jr. Takes Aim at the Political Establishment

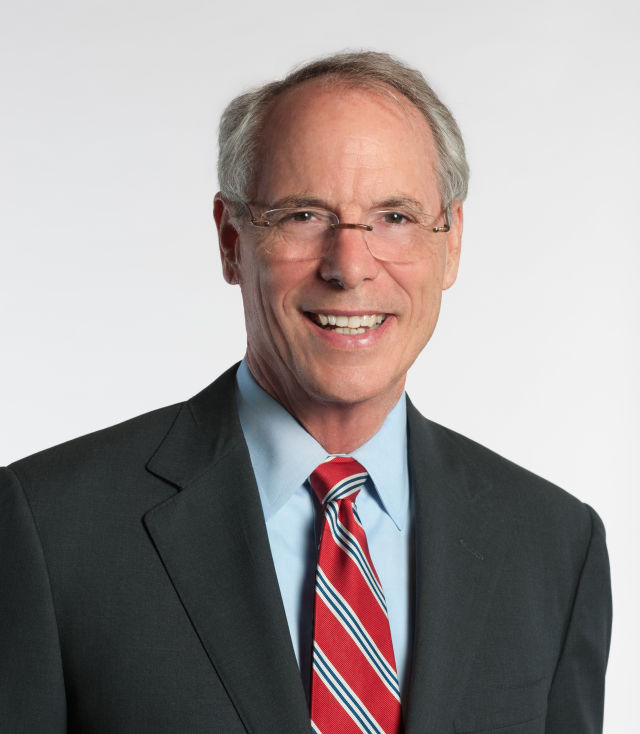

On a recent morning, Hugh Culverhouse Jr. traveled from his home in Coral Gables to his office in Palmer Ranch, where he oversees one of the region’s largest and most valuable real estate holdings. At 70, Culverhouse is lean and fit and speaks in a soothing drawl culled from his Alabama childhood. He is wearing a conservative tie, pressed blue shirt, khaki pants. His full head of dark hair recalls Don Draper on Mad Men. On his desk, a Bloomberg terminal projects four screens of financial headlines, data, bar charts and price quotes, allowing Culverhouse to track his investments (hedge funds, oil and gas). Along an office wall, a massive stereo system—Culverhouse has more than 1,500 CDs, from classical to country to R&B—is pumping out jazz pianist Don Shirley.

The phone rings. Calling is University of Alabama president Stuart R. Bell. Last year, Culverhouse and his wife, Eliza, gave the university’s law school $26.5 million, the largest gift in Alabama’s 187-year history, resulting in the law school’s becoming the Hugh F. Culverhouse Jr. School of Law. Bell is calling to talk about Japanese woodblock print art. Thirty-six years ago, on his honeymoon in San Francisco, Culverhouse says he “gathered my courage” to step into a Japanese art shop. He has spent subsequent years amassing one of the largest collections in the country, much of which he intends to give to Alabama.

It looked to the world as if Culverhouse and his beloved Crimson Tide would roll together happily ever after. But in May, the Alabama Legislature passed the nation’s most restrictive anti-abortion law, enraging Culverhouse, who has a long history of supporting women’s reproductive rights. Culverhouse, as is his wont, didn’t merely pen a letter of protest or sign his name to a petition. He called for a full boycott of Alabama institutions, including urging prospective students to go elsewhere, an astonishing act for the largest benefactor in the school’s history and one that put him in the national spotlight. The University of Alabama responded by voting to return the money it had already received from Culverhouse, nearly $22 million, and removing his name from the law school before the paint had dried. The university then accused Culverhouse of not honoring his previous donation and trying to manipulate school policies. Culverhouse is not backing down, and wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post, urging people to take a stand against lawmakers who are restricting abortion rights across the country.

Pat Neal

Image: Courtesy Photo

Alabama was discovering what Sarasota County political leaders have been witnessing for the past two years. With a zeal and ferocity—not to mention a bottomless pile of cash—that command both respect and fear, Culverhouse has quickly become one of Sarasota County’s leading power brokers. No, he’s not Pat Neal, the mega-developer who has enormous influence in the local Republican Party. But unpredictable and unbound to any group, Culverhouse has hit the region like a land mine.

He played important roles in three of the biggest defeats Sarasota’s old guard has suffered in recent decades: Democrat Margaret Good’s election as state representative, the approval of election districts for county commissioners, and Judge Maria Ruhl’s election to the circuit bench, the first time since 1998 that a challenger had defeated a sitting judge in Sarasota County.

“Almost certainly those outcomes would have happened to a lesser degree, if at all,” says Dan Lobeck, a Sarasota attorney and head of the watchdog group Control Growth Now.

“Hugh tipped the scales,” agrees Sarasota School Board member Eric Robinson, a former chairman of the county Republican Party. What makes Culverhouse so formidable, Robinson adds, is that “Hugh is motivated by doing what he believes is the right thing, not just what’s best for Hugh. Those people always fight the hardest.”

For decades, Culverhouse caused hardly a ripple in local political currents. In the 10 general state elections between 1994 and 2004, according to state records, he donated less than $40,000 total. In 2012, he gave $30—in the form of six $5 donations, all to a committee representing the Pinellas County Teachers Association. But in the spring of 2015, a startling ruling was rendered in a Sarasota County courtroom. A jury had awarded Culverhouse $20 million in a lawsuit he filed against two prominent developers, Henry Rodriguez and Randy Benderson, in which Culverhouse accused them, in cahoots with the Sarasota County Commission, of double-crossing him in a deal to develop 1,000 acres in Sarasota County. But in what the Sarasota Herald-Tribune described as a “normally routine post-trial hearing,” Judge Peter J. Dubensky ruled there was not enough legal basis for the jury’s award. Instead, he granted Culverhouse a pittance—$153,000.

Culverhouse saw the decision as one more example of the established power structure sticking together, and it galvanized him.

His first target was the 12th Circuit bench, where he says he found “the Florida Constitution” being massively subverted by a “patronage system.”

Judge Maria Ruhl

Image: Courtesy Photo

Under the Constitution, Florida voters elect judges who preside over criminal and civil cases. But in practice, something different was taking place. Sitting judges were deciding to resign early—sometimes just days before the qualifying period for new candidates to file—allowing governors to appoint their replacements rather than new elections to be held. Critics say the strategy undermines democracy, enabling governors and their local supporters to shape the judicial system for years to come. That practice accelerated under former Republican Gov. Rick Scott, who appointed 241 judges, according to Ballotpedia, almost double the number appointed by Jeb Bush, also a two-term Republican. Fueling Culverhouse’s outrage was that the man who heads the 12th Circuit Judicial Nominating Committee for Sarasota, Manatee and DeSoto counties is power broker Pat Neal.

Appointed judges eventually face election by voters. In reality, though, few candidates are willing to challenge a sitting judge, especially one nominated by the region’s political leaders. Before last year, the last time a sitting judge had been challenged in the 12th Circuit was 2006. That didn’t deter Culverhouse.

His first target was incumbent (and Gov. Scott-appointed) Judge Brian Iten, who had replaced Dubensky, the judge who threw out the $20 million judgment against Rodriguez and Benderson. Culverhouse gave thousands and key advice (where to place yard signs, for instance) to challenger Maria Ruhl, a Bradenton attorney who lives in Venice. The outcome was stunning. Ruhl became the circuit’s first Hispanic judge, capturing 63 percent of the vote over Iten, whose backers included Pat Neal.

“From what I heard, I shook up the courthouse,” Culverhouse says. “I’m not done yet. To everyone at the courthouse who thinks they are the king or the queen, they’ll learn how insignificant they really are. If I ran a slate of 30 candidates, I’ll make you a prediction: 15 would win. So, I wouldn’t piss me off.”

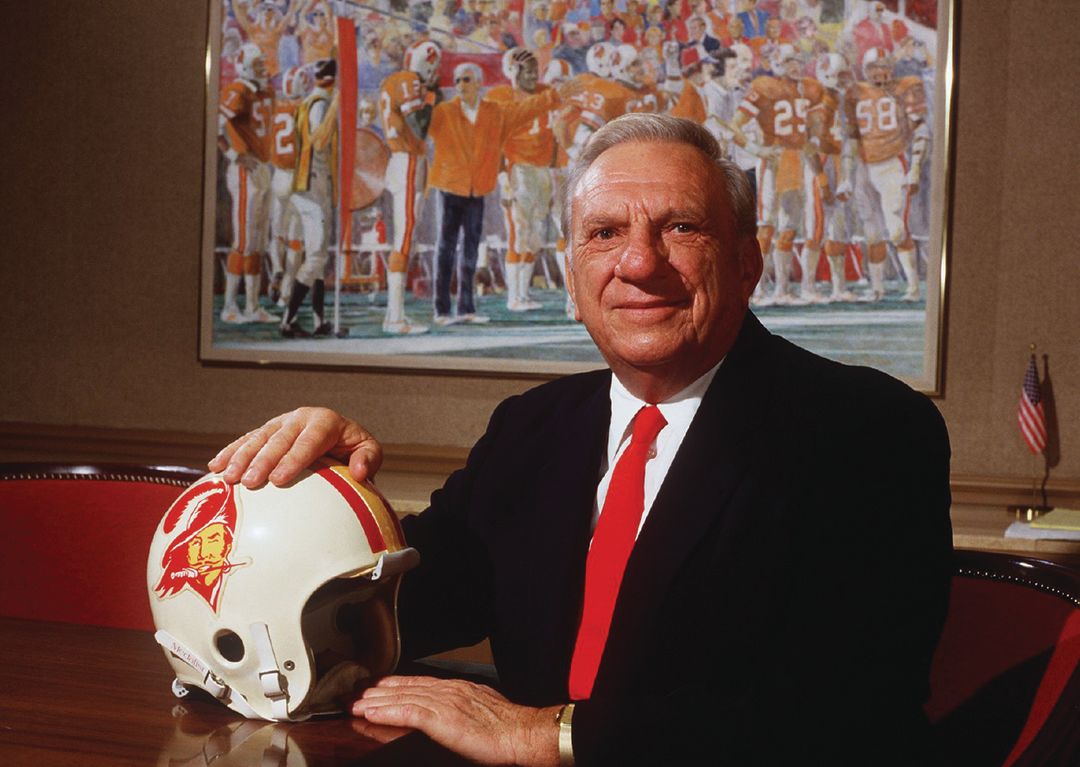

Hugh Culverhouse Sr. was the first owner of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

Image: Tampa Bay Times

Famous family, infamous finales

Hugh Franklin Culverhouse Jr.’s parents were both larger than life and painfully human. His father, Hugh Sr., boxed with George Wallace at the University of Alabama, became a U.S. attorney celebrated for sending mobsters to prison, and then turned to private tax law and real estate investment, which made him a fortune valued at his death at $381 million. He was the first owner of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and a major player in Florida real estate, whose acquisitions included 12,000 acres of Palmer Ranch in the heart of Sarasota County. Culverhouse’s mother, Joy, was a remarkable figure in her own right, becoming the first woman to win an athletic scholarship to Louisiana State University, where she played on the men’s golf team. She went on to become one of the top female amateur players in the South, as well as a philanthropic leader and the No. 1 fan of Tampa Bay’s first pro football team.

But there was another side to Hugh Sr. Known as “Mr. C,” he was described by a writer for the Associated Press as a “short, squat, cigar-smoking man with a heavy Southern drawl, a red, bulbous nose like W.C. Fields’ and a fondness for light orange sports jackets.” The year before he died in 1994 at the age of 75, Hugh Sr. had his wife of 52 years sign a post-nuptial agreement that granted her just $5 million and a condo, with most of his assets going into a trust. A subsequent lawsuit revealed Hugh Sr. to be a chronic philanderer, whose infidelities included affairs with his 40-year-old receptionist and with Susan Brinkley, the wife of former NBC News anchor David Brinkley.

Culverhouse testified in court, according to coverage at the time, that his father would take Susan Brinkley to his ranch in Sarasota, where the caretaker would take “them into the woods where they would shoot guns and basically have sex.” Culverhouse testified he was so upset by his father’s conduct that he wrote him a letter urging him to end his philandering or at least be discreet. “If you can’t do that, by God, get a divorce,” Culverhouse wrote, according to the AP.

After Hugh Sr.’s death, when Joy Culverhouse came to see the full picture, she famously quipped: “I’d like to pull him out of the grave and shoot him with every bullet I had.”

Joy Culverhouse

Image: Tampa Bay Times/Zuma Wire

Unfortunately for Culverhouse, his mother did not go any more gently when she died in 2016 at 96. Addled by age and alcohol, reports at the time said, Joy Culverhouse had remarried a man 15 years her junior and disinherited her two children, Culverhouse and his sister, Gay. Daniel Ruth, a columnist for the Tampa Bay Times, wrote that if they made a movie about Joy Culverhouse, it would be a combination of The Shining and Mommy Dearest. Her ashes were held at a funeral home for a year while her heirs sued over her estate. Finally, they were delivered to Culverhouse in Coral Cables. He decided against spreading them across the University of Alabama golf course, instead burying them in his back yard, where he plans for his own ashes to be buried with his beloved cats. “At least I’ll have someone to fight with when I die,” Culverhouse said in 2017. That would at least be a start. He and his mother did not speak the last 13 years of her life. His sizable inheritances came only after he sued both his father’s and mother’s estates, cases that brought the family’s soiled laundry into public view.

But at an interview in his office at Palmer Ranch, Culverhouse was sanguine about his parents. “Everybody thinks that the way your parents are at a specific time is the way they were when you grew up,” he says. “But that’s not true. My mother became an expert at drinking vodka and my father became an expert at owing money. But they were not always like that.”

When he recalls his father, Culverhouse cites his dedication to justice as a U.S. attorney and his insistence that his son put his country above himself. Hugh Sr. paid for his son’s undergraduate and law school under the agreement that after Culverhouse earned his degrees, he would give his first five years to government service.

Joy Culverhouse was no softy, her son recalls, but “if something was really bothering me, I could call time out and tell her whatever it was, and she would be the sweetest and most helpful person in the world. When it was over, and I was OK, she would snap back to being Joy.”

Culverhouse says his mother fortified the determination that has become one of the biggest factors in his own success. After law school, Culverhouse took a job with the Securities and Exchange Commission, but he grew disillusioned by the organization’s weak enforcement. In one case, con artists sold worthless government bonds to a Texas doctor, wiping out his life’s savings and leading him to kill himself. When a judge let the con men off and Culverhouse watched them laughing as they walked out of the courthouse, Culverhouse decided to go to work for the Justice Department, where he could send crooks to prison. The move did not come easily. Despite having a father who was a legendary prosecutor and his own credentials—a law degree from the University of Florida, an M.B.A. from New York University and being a Certified Public Accountant—Culverhouse applied for 33 jobs as a U.S. attorney and was rejected for all of them. Finally, he landed a position in Miami, where he lost three of his first four cases and became despondent. His mother told him, “Goddamn it, Hugh, you can do this job. If I ever hear you talk about quitting again, I’m coming down to Miami and beating you senseless with a two iron.” Working 80-hour weeks, Culverhouse went on to try more cases that year than any prosecutor in his district and win 24 of his next 26 cases.

An armchair analyst might suggest that as much as Culverhouse was shaped by his parents, he was also driven not to repeat the mistakes of his father. Hugh Sr. had been an astute businessman in many ways, but also an undisciplined one. His estate included $300 million in debt. Culverhouse took his inheritance in land, specifically 7,000 acres in Palmer Ranch, eventually acquiring thousands of acres more, including land from his mother’s estate. He resold the land for development and used the proceeds to pay off the debt, living on earnings from his investing and legal work. “I hate debt,” Culverhouse says, “and for the last 13 to 14 years we have not had one penny of debt.” He says his net worth is now “several hundred million dollars.”

In the 1980s, when his first marriage was ending, Culverhouse met Eliza Perlmutter, the glamorous daughter of a renowned South Florida neurosurgeon, at a gym. He challenged her to a game of racquetball, with the loser buying dinner. “She skunked me,” Culverhouse recalls. He had to wait a year to pay off his bet because Perlmutter refused to go out with him until her own divorce was finalized. The wait turned out to be worth it. The Culverhouses have lunch dates three or four times a week, take long walks on the weekends and work closely on philanthropic efforts.

Another area in which Culverhouse differs from his father is his generosity. Hugh Sr. gave millions to charities, but he was also known as a tightwad. “My dad always had a problem paying people,” Culverhouse says. “He was extremely cheap for anyone who worked for him.” Hugh Sr. paid Doug Williams, the first black quarterback to lead a team to victory in the Super Bowl, just $120,000, by far the lowest salary of any starting quarterback in the league. His son has given $68 million to charities and plans another $5 million gift this year, which he is not ready to disclose.

Hugh Culverhouse Jr. owns thousands of acres that are now Palmer Ranch, a community of 25,000 residents that is still growing.

Sensitive Development

Although he is one of the largest landowners in Southwest Florida, Culverhouse bristles at being called a developer. He’s an “attorney and investor,” he says, one who is selling the land for others to develop. And there is a lot of land.

Palmer Ranch was purchased in 1910 by pioneering Florida real estate investor Bertha Palmer, a Chicago socialite and philanthropist. Hugh Culverhouse Sr. bought 12,000 acres from the Palmer heirs in 1972. Today, Palmer Ranch ranks with Lakewood Ranch to its north and the West Villages to the south as one of the largest development areas transforming Southwest Florida. Palmer Ranch has around 11,000 homes, 25,000 residents and 700,000 square feet of commercial space. Culverhouse still owns so much land, including 2,400 acres east of Interstate 75, that development is projected to continue for decades.

Culverhouse says he sells only to national builders because they have the deep pockets to withstand a recession. He puts an emphasis on green space that goes far beyond county requirements: 50-foot buffers along main roads, for example, compared to 10 feet required by the county. Many developers create Community Development Districts that require residents to pay for infrastructure such as roads and sewers, a practice that critics consider double taxation. Culverhouse doesn’t allow developers to use such districts. He donated 100 acres for a community park in the heart of Palmer Ranch, the largest community park in the region.

Reid Ewing, a distinguished professor of city and metropolitan planning at the University of Utah, has cited Palmer Ranch as one of six case studies about large-scale Florida developments that have used best development practices.

“Hugh is not without flaws, but he’s certainly more responsible than most,” Lobeck says. “He’s one of the rare developers who believes in reasonable controls and is sensitive to connectivity and green space.”

Challenging the establishment

In politics, Culverhouse marches only to the beat of his own drummer. In a 2018 special election, for example, he decided to back underdog Margaret Good for state representative against James Buchanan, the son of longtime Sarasota Congressman Vern Buchanan. Culverhouse says he knew attorneys at the firm in which Good worked who touted her integrity. He also thought, as a Democrat, Good would bring badly needed diversity to an area long dominated by Republicans.

Rep. Margaret Good

Image: Courtesy Photo

Culverhouse recalls that before he met with Good, he received a call from Vern Buchanan, who pleaded with Culverhouse that if he could not support Buchanan’s son, to at least stay out of the race. Culverhouse refused. But within a year, he met with James Buchanan, and supported his election to the Florida House in a different district.

“Jimmy is a good kid,” Culverhouse says. “I liked him, just not running against Margaret Good.”

Sarasota attorney Morgan Bentley laughs about Culverhouse’s ability to separate the personal from the political. Bentley says he was reading an online newspaper story about one of his own cases when he came across a signed comment by Culverhouse at the end of the article “basically calling me an idiot. Then my phone rings. It’s Hugh wanting to go to lunch. That’s Hugh. I’ve been to parties at his house, and the guests include people he’s sued.”

Bentley, who represented Rodriguez in the Culverhouse case and has also represented Neal, considers Culverhouse “one of the toughest opponents you are ever going to come across.”

“I give Hugh a lot of credit for how effective he has been so far politically,” Bentley says. “The results have been amazing. But let’s be clear: He’s motivated by a lot of self-interest. He sees the system as favoring developers like Pat Neal, Carlos Beruff and Randy Benderson, and Hugh is out to level that playing field. I don’t blame him for that.”

Bentley says he understands Culverhouse’s motivation, but he disputes the premise that the county is controlled by a political cabal headed by Neal or that the 12th judiciary has been corrupted by a patronage system. Developers such as Neal have a large stake in how county government operates and good reasons to be politically active, Bentley says. The judicial nominating committee, long headed by Neal, nominates multiple candidates to the governor, which leads to further vetting, Bentley says, adding that the system appears to be effective because the 12th judiciary is one of the most respected in Florida.

Asked to comment about Culverhouse, Neal offered only praise, calling him “smart and engaged” and a “strategic thinker.”

Culverhouse does not always stick to such niceties. When he felt that the Herald-Tribune was not adequately covering his lawsuit against Benderson and Rodriguez, Culverhouse began funding Jon Susce’s alternative publication, The Sarasota Phoenix, which is known for its scathing—and sometimes incoherent—attacks on Neal, Benderson and other political and business figures. Susce refused to comment about the arrangement, but Culverhouse, who seems constitutionally incapable of dodging a question, says he has funded Susce, and that a former Herald-Tribune reporter wrote articles for the Phoenix under Susce’s name, ripping Benderson, Rodriguez and the county commissioners. “It was too clearly written to have been Jon’s work,” Culverhouse says with a smile.

Culverhouse donated $100,000 to Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody's campaign.

Image: Courtesy Photo

Culverhouse donated $358,693 to Florida candidates during the 2018 election, including more than $100,000 to Ashley Moody, a Republican, who was elected Attorney General, and $128,000 to Gwen Graham, a Democrat who lost in the gubernatorial primary. In another stark testament to his pragmatism, Culverhouse donated more than $30,000 to conservative political action groups such as Florida Conservatives United and $35,000 to the Democratic political action committee, New Day Florida.

“He is not a typical developer,” says Rita Ferrandino, former chairwoman of the Sarasota County Democratic Party. “He is not tied to a single political party.”

Jack Brill, chairman of the Sarasota County Republican Party, adds, “Hugh is a candidate- and issue-specific donor, which you don’t see very often.”

Culverhouse says his political involvement comes down to a change in his philosophy. For many years, he was known as a serial litigator, whose first act in solving a problem usually started at the courthouse. “But I’ve come to see a lawsuit is like using a shotgun. You can hit the target but it’s only one person,” he says. “With elections, you can change the system. And that is what I intend to do. They don’t want to play poker with me because I have all the chips and I’ll use as many as I need. I don’t even have to win every hand. I can bleed them out.”

But those efforts are not intended to stack the deck in his favor, he says. After Ruhl’s election, for example, Culverhouse says he called to congratulate her and wish her success on the bench. “And then I told her, this is the last time you’ll ever hear from me.”

Photo of Hugh Culverhouse Jr. by Zach Riggins, the University of Alabama.

A former newspaper editor and co-editor of (941)CEO, David Hackett is a frequent contributor to Sarasota Magazine.