Six-Term Republican Congressman Vern Buchanan Walks a Tightrope in the Age of Trump

In mid-July, Congressman Vern Buchanan of Longboat Key spent $500,000 on a television ad accusing his Democratic opponent David Shapiro of profiting from everything from oil spills to opioid addiction to “cop-killer bullets.” The claims were based on mutual fund investments from Shapiro’s retirement account, which he does not manage. What was most striking about the ad, however, was not its tenor, but its timing: Buchanan, who has easily won re-election five times, has seldom needed to attack his opponents, let alone launch a preemptive strike months before a general election.

“I about fell out of my chair when I saw it,” says Keith Fitzgerald, a political science professor at New College. “A six-term incumbent doesn’t put an ad like that out in July unless he believes he has a race on his hands.”

Fitzgerald is a Democrat who ran unsuccessfully against Buchanan in 2012. But his views are widely shared outside Sarasota. National nonpartisan analysts the Cook Political Report and Sabato’s Crystal Ball by mid-summer had changed their forecast in the race from “likely” to “leans” Republican, just one rung above a toss-up. Bracing for a fight, the Buchanan campaign reserved $3 million in fall advertising, more than three times what the campaign spent in its entire 2016 campaign, Politico reported. Shapiro, 58, the son of a dry cleaner who has been a personal injury attorney in the area for 30 years, qualified for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee’s “Red to Blue” status—giving him national support and money that previous Democrats have lacked against Buchanan.

“When you consider all the factors, Vern Buchanan is facing the most hostile election environment he has been up against since he first ran in 2006,” says David Wasserman, House analyst for the Cook Political Report. “We changed our forecast for the district because we have seen several warning signs, including that he has a fairly strong opponent this time.”

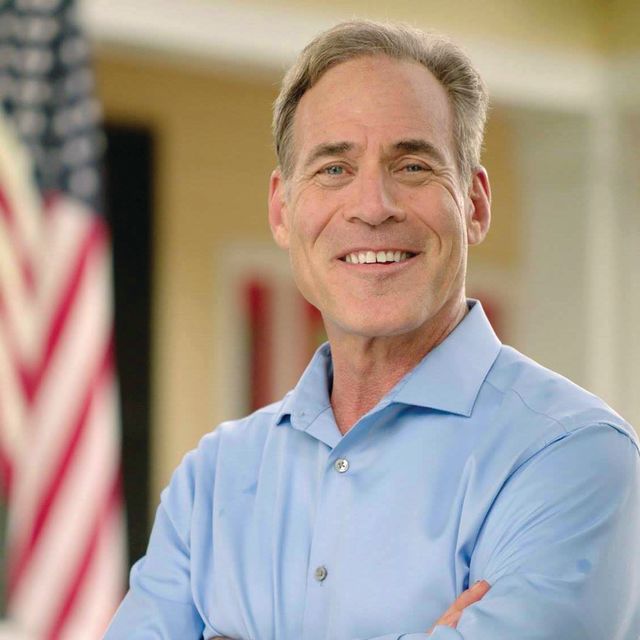

David Shapiro, Buchanan's Democratic challenger.

Image: Courtesy Photo

Buchanan’s challenge is mirrored in House races across the country, where Democrats are hoping for a blue wave similar to the Tea Party-led Republican backlash in 2010 that gave the GOP control of the House. National polls show Democrats with up to double-digit leads in generic ballots that only ask which party a voter is supporting. Polls show Democrats winning in places that President Trump easily carried just two years ago. A record number of Republicans are bowing out, rather than seeking re-election, including House Speaker Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, Trey Gowdy of South Carolina and Tom Rooney, who represents Buchanan’s neighboring 17th District.

What sets Buchanan apart, however, is how he has responded to the challenge. It involves a balancing act so precise that it might bring a smile to one of Sarasota’s most famous sons, Nik Wallenda. While trying not to rile his conservative base, Buchanan is claiming the line as a bipartisan leader, willing to cross President Trump and Republican leadership on issues that resonate in the district, such as water pollution, animal protection and children’s health. It’s a strategy not without risk. Buchanan cannot afford to lose the Trump base, which represents much of the Republican Party. At the same time, he must persuade moderate Republicans and independents. As one GOP insider summed up, “He is a Chamber of Commerce Republican, not one of the Trump crazies.”

Viewed from ground level, the image of Buchanan floating above the nation’s great partisan divide is hard to visualize. According to the FiveThirtyEight website, which tracks how members of Congress vote in relation to President Trump’s positions, Buchanan through July supported Trump 96.5 percent of the time, a higher percentage than even the president’s ardent supporters in the House, including Matt Gaetz of Florida, Jim Jordan of Ohio and Mark Meadows of North Carolina. It’s a statistic that Buchanan is avoiding like an ugly sweater gifted to him on Christmas.

Instead, Buchanan’s campaign eagerly sends a lengthy list of the times he has bucked not only Trump, but Republican leadership in Congress. Buchanan was one of only 19 Republicans, for example, to vote against Trump’s move to rescind $7 billion for the Children’s Health Insurance Program. He also was one of 15 Republicans to vote against the House Interior Appropriations bill, which would have slashed $165 million from environmental protection and land and water conservation. Buchanan successfully pushed an $8 million appropriation this year to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to study red tide.

Buchanan also has been willing to stand up to Trump publicly. After the president in his summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin dismissed U.S. intelligence findings that Russia interfered in the U.S. election, Buchanan tweeted: “Russia is not our friend. There is no dissent inside U.S. intelligence agencies that Russia interfered in the presidential election.” A week later, Buchanan was on Twitter again, rebuking the president on another topic: “The Trump administration must immediately withdraw its plan to weaken the Endangered Species Act. The proposal amounts to an assault against nature and will lead to the extinction of wildlife.”

Those positions aren’t coming from political calculations, says David Jolly, a former Republican Congressman from Tampa and an MSNBC cable news contributor who served alongside Buchanan for several years in the House. “That’s who Vern is and who he has been,” Jolly says. “He has always been a very mature voice in what can be a very immature environment. That’s why he has been such a leader as co-chairman of Florida’s delegation. He’s willing to reach across the aisle and find compromise.”

Jolly views Trump as such an existential threat that he is rooting for Democrats to defeat his own party for control of Congress. “But I make one exception,” he tells me. “Vern Buchanan.”

But unlike Jolly, who has no electorate to sway, Buchanan cannot afford to dismiss Trump. The president, whose approval rating among Republicans has perched at nearly 90 percent, according to Gallup, cast a powerful shadow in the governor’s race. Adam Putnam, the state’s agricultural commissioner, had long been viewed as the favorite to win the GOP nomination and was leading by 15 points in a June Fox News poll. But then little-known Congressman Ron DeSantis played the Trump card. The president tweeted out his endorsement in late June, and soon after DeSantis began running what Rolling Stone magazine called “what may be the most bizarre” TV ad of the campaign, showing DeSantis’ children garbed in “Make America Great Again” clothing, reading them Trump stories at bedtime and helping them with blocks to “build the wall.” In one of the most astonishing turnarounds in recent Florida political history, Putnam in a month went from a double-digit advantage to trailing by 17 percent in the polls and was demolished by DeSantis a month later in the primary.

Buchanan was more fortunate than Putnam because he did not face a primary challenger, where the party base plays an outsized role. But the Trump effect cannot be ignored. Even before Trump won the White House, Sarasota County Republicans not once, but twice—in 2012 and 2015—named him their Statesman of the Year.

Yet when asked about whether he would beckon Trump to return to Sarasota to campaign on his behalf, Buchanan gave a long answer with no affirmation, plenty of hedging and a conclusion that ended up at the Humane Society.

“I’ve got my own record, and that’s what I’m going to run on,” Buchanan says. “If it makes sense for our area, I’ll agree with Trump. If it doesn’t make sense for our area, I’ll say so publicly, which I have done on offshore oil drilling and the Paris Climate Accords. I think the [Mueller] investigation needs to go forward. Wherever it leads, it leads. I have a full plate and my focus is on issues that matter to this area. I chair the Animal Protection Caucus in the House and, in fact, I was at the Humane Society in Sarasota yesterday touring their new facility. It’s pretty exciting what they’re doing …”

That response is unlikely to motivate enthusiastic Trump supporters such as Kathy Schille, a local real estate agent who considers herself one of the “adorable deplorables.” Schille says she “likes Vern Buchanan. I’ve been to his house. But I’m on the fence. If he is going to divide himself from Trump, then he won’t get my vote. I want someone who supports the president’s agenda. And not just what he says. I want to hear President Trump say he is behind Vern Buchanan.”

Buchanan’s district, which includes much of Sarasota County, all of Manatee County and a slice of Hillsborough County, has thousands of voters like Schille who helped Trump win by 11 percent over Hillary Clinton. Buchanan risks alienating his base by distancing himself from Trump. One of Florida’s top Republican campaign strategists, speaking on condition he not be named, says Buchanan is likely running a two-front campaign, portraying himself as bipartisan in television ads but at the same time using target messaging on social media like Facebook to reassure the conservative base. “For those Trump Republicans, two issues really matter: guns and immigration,” the strategist says. “And Buchanan is reaching them under the radar. They’re going to turn out for him.”

For hardcore conservatives, Buchanan’s record on those issues is hard to challenge. He received a 93 percent approval rating in 2016 from the National Rifle Association, and zero percent from the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence. On immigration, the ultra-conservative Federation for American Immigration Reform gave Buchanan a 100 percent rating.

Congressman Vern Buchanan on the steps of the U.S. Capitol.

Image: Bill Clark/Associated Press

Vern Buchanan turned 67 last May. At 6-feet-4-inches with a full head of brown hair, Buchanan has the confident gait of both a jock and the top boss of a fleet of car dealerships. Sore knees forced him to give up one of his passions, basketball, so he now embraces cycling, pedaling up to 3,000 miles a year.

He and his wife Sandy, who met in college, have been married since 1976. Just as unusual, by Congressional standards, Buchanan still has the same chief of staff, field officer and political director that he did from his first days in office. One of his two sons, James, is seeking to follow his father into elected office, running this fall for state representative.

If there is one thing that separates Buchanan, however, it is his wealth, gleaned from 40 years as a business owner of print shops, car dealerships and real estate. His path to riches has had several controversial turns. His chain of American Speedy printing shops in Michigan went bankrupt soon after he resigned and he was sued by former franchise owners. In 1999, after rebuilding his business reputation in Sarasota, Buchanan was frozen out of a deal to develop the Ritz-Carlton, Sarasota after other developers questioned whether Buchanan had overstated his assets.

Buchanan persevered and now ranks as the eighth richest person in Congress, with a net worth of more than $73 million, according to Roll Call, allowing him to live in the realm of the top 1 percent. In January, an Amtrak train carrying Republican House members and staff to a retreat in West Virginia was involved in a harrowing accident when it was hit by a truck. But a quick check showed Buchanan was safe: He had arrived at the event hours earlier in his Embraer Phenom 300 private jet.

After his first two or three terms, Buchanan was approached to run for governor or Senate. Buchanan says he was flattered. But instead of seeking higher office, he put his head down and focused on moving up the ladder, rising from a back-bencher to one of the senior members of the House Ways and Means Committee, where he chairs the tax policy subcommittee and is the state’s highest-ranking member since Republican Clay Shaw a decade ago. Buchanan is also the co-chairman, with Democrat Alcee Hastings, of Florida’s Congressional delegation, a position he says is vital to pass legislation for Florida such as a bill to help citrus farmers struggling with greening disease, which Buchanan authored and which was signed into law in January.

“I’m a blue-collar kid whose parents worked in factories and who did better than I ever thought I would in business, and now I’m enjoying public service,” he says. “With my role on Ways and Means, which is the most powerful committee in Congress, where nearly $2 trillion flows through every year, I can have a tremendous impact for our district. And I say this humbly, with my role on Ways and Means and as co-chair of the Florida delegation, I am Florida’s most effective representative in Congress.”

Nonpartisan analysts support Buchanan’s claim. The Center for Effective Lawmaking, a joint effort from the University of Virginia and Vanderbilt University, rated Buchanan second only to former Republican Rep. Jeff Miller, who retired in 2016, for the 2015-2016 session, among all the state’s House and Senate members. In its Bipartisan Index, The Lugar Center at Georgetown University ranks Buchanan 67th out of 435 House members.

One issue that has driven Buchanan since he took office is the soaring federal debt, which he calls “immoral.” He has authored balanced budget bills, including one that would deny Congress a pay raise in any fiscal year that it did not balance the budget, proposals that went nowhere. Nonetheless, Buchanan voted for last year’s tax cuts despite warnings from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office that the changes would increase the federal debt from $21 trillion to $33 trillion in a decade. The tax cut flowed from the Ways and Means Committee, meaning Buchanan had more power than many members to influence the legislation.

Buchanan reconciles his vote to cut taxes with his demand for a balanced budget. What the government was doing wasn’t working, he says, and he saw the cuts as a chance to jumpstart the economy. Under President Obama, Buchanan says, the national debt increased by $10 trillion and the economy grew at only 1.5 percent. What Buchanan doesn’t say is that the biggest deficits under Obama, more than $1 trillion annually, came in his first term during the trough of the Great Recession and came down to around $500 billion annually in Obama’s final two years. Buchanan’s assertion on GDP growth under Obama is also misleading. From 2010 to 2016, as the nation’s economy recovered, annual GDP was 2.2 percent or higher four times and never was below 1.6 percent.

Democrats have seized on Buchanan’s purchase of an Ocean Alexander yacht; above, the $3.25 million 70 E yacht, Ocean Alexander’s least expensive.

Image: Forest Johnson

That kind of numerical nuance can go over like a double-dose of Ambien in a general election, so Democrats have seized instead on a gaudy symbol of money-driven self-interest, specifically an Ocean Alexander yacht that Buchanan purchased on Nov. 16, 2017. The timing could not have been better for his critics. The purchase came on the same day that Buchanan joined 226 Republicans and zero Democrats in voting for the tax cut, which reportedly will save Buchanan more than $2 million annually. Buchanan’s campaign refused to reveal the make or price of the yacht, but the cheapest Ocean Alexander vessel goes for $3.25 million.

Floridians for a Fair Shake, a left-leaning advocacy group not tied directly to Shapiro’s campaign, is targeting the yacht in an effort to sink Buchanan’s campaign. The group not only spent $600,000 on an ad lambasting Buchanan, it started a website called vernsyacht.com, a Twitter handle with the same theme and a billboard in Sarasota replete with a doctored photo of a smiling Buchanan in a goofy boat captain’s hat. The group even took out a newspaper ad offering $500 for a photo of the yacht.

Shapiro says the yacht is emblematic of “trickle down economics” in which the rich get richer, while millions of Americans struggle to afford health care and other basic needs.

“That’s just nonsense, part of the silly season,” Buchanan says. “I’ve been a boater for 30 years and anyone can tell you that you don’t decide to buy a boat on one day. And beyond that, if I want to buy a boat or a house after working 40 years in business, I don’t know what’s wrong with that. It has nothing to do with the issues I hear from constituents. They’re concerned most about the dysfunction in Washington, and fixing that is where my efforts are focused.”

But the yacht story showed no signs of sailing away. MapLight, a journalistic website focusing on money in politics, reported that Buchanan received a “seven-figure” loan for the yacht purchase from BMO Harris Bank, which had been lobbying the Ways and Means Committee on the tax cut legislation. MapLight, citing Coast Guard records, said the yacht was 73 feet and named The Entrepreneur.

Buchanan broke with Trump to protect a children’s health insurance program and the environment.

Image: Shutterstock

On the surface, Shapiro has commonalities with Buchanan. Both have built successful businesses—Shapiro is a founder and partner in his law firm—are partners in long marriages, cite devotion to their children and have a lengthy list of community service, including as board members of the chamber of commerce.

On the issues, however, Shapiro says the differences between him and Buchanan are night and day. Shapiro supports developing a “green economy,” saving and improving the Affordable Care Act and gun control. He says that Buchanan’s efforts to portray himself as bipartisan leader “doesn’t square with his record in Washington.” Buchanan voted 16 times to repeal the Affordable Care Act, voted for a tax cut that disproportionately benefits the rich and failed to push for proactive environmental protections to address grave threats to the region, such as rising sea levels. While Buchanan highlights the research funding he secured for Mote Marine to study red tide, Shapiro says Buchanan was quietly taking $109,000 in campaign donations from Florida sugar growers, whose runoffs are thought to worsen red tide.

“He says he cares about the environment, but he has a 9 percent rating from the League of Conservation voters,” Shapiro says. “If it doesn’t wash up on the shores here, he’s not interested.”

Local Democrats have been trying for years to persuade Shapiro to run after he showed his potential in 2006. In a race for State House, Shapiro garnered 49.4 of the vote in a district in which Republicans outnumbered Democrats 2 to 1. But it took more than a decade to convince Shapiro to try again.

If there is a model for a Shapiro victory, it might be the special election for Florida State House District 72 last February in which Democrat Margaret Good gained national attention by winning by 7.4 percent. There is little doubt that Good’s surprising victory caught the attention of Buchanan. The candidate she defeated was Buchanan’s son, James.

But it may be Trump and not David Shapiro who casts the longest shadow in this election.

As the investigation into Trump deepens, it threatens to flip the adage that “all politics is local” into “all politics is about Trump.” And if an anti-Trump wave blows through the election, it could shake the footing of even a six-term incumbent trying hard to perform a balancing act.