A New Book From a Sarasota Native Tells the Story of the Fight to Save the Everglades

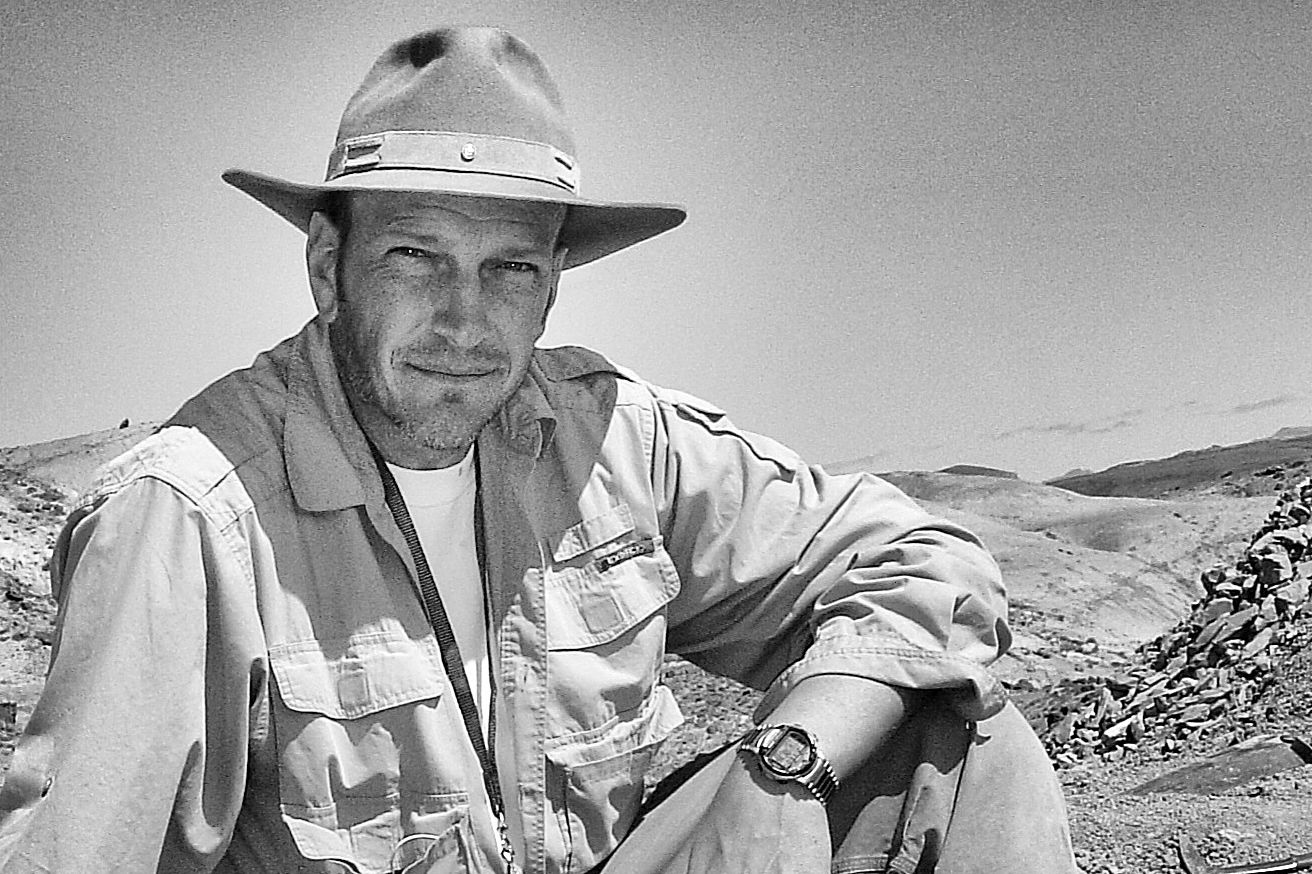

Amy Green.

Image: Tony Pernas

Sarasota native Amy Green is a reporter who covers environmental issues for WMFE, the National Public Radio affiliate in Orlando. She's also the author of a new book, Moving Water: The Everglades and Big Sugar, which traces the convoluted history of how activists pushed the state of Florida and the federal government to begin taking steps to restore the Everglades after decades of pollution and neglect, as well as the slow, painstaking process of actually restoring Florida's famed "River of Grass."

Green is participating in a Zoom discussion hosted by Bookstore1Sarasota that starts at 2 p.m. this Thursday, April 22. There is no charge for the event, but the bookstore is asking for $7 contributions from attendees. Register here.

Green recently spoke to Sarasota Magazine about how she became interested in the Everglades and why all Floridians should care about its future. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What was it about the Everglades that captured your imagination?

I got sucked into this story back in 2008. The governor at the time, Charlie Crist, had unveiled a plan to buy out U.S. Sugar, the nation's oldest and largest sugar producer, and put the land toward Everglades restoration.

I started working on a story for Newsweek about The Everglades Foundation, which was deeply involved in the negotiations. During the course of reporting on that article, I called Mary Barley, whose husband, George Barley, established the foundation. For two single-spaced typed pages, she told me the story of The Everglades Foundation, which was really her own story. I could immediately see that Mary had lived an extraordinary life.

A few weeks later, I drove down to Islamorada in the Florida Keys, where Mary lives. I interviewed her and wrote another article for the The Christian Science Monitor. While reporting on that article, I went into Everglades National Park with Mary and Tom Van Lent, a scientist for The Everglades Foundation.

I can remember Tom explaining to me how, after a roadway was built through the River of Grass, the roadway served as a dam and the vegetation on one side of the road changed and was different than on the other side. He explained to me how this had to do with the flow of the water in the Everglades and the distribution of nutrients, and how this subtle change in the flow of water dramatically changed the vegetation and the landscape on one side of the road. I just thought this was the coolest thing. I was hooked right then and there, and wanted to learn everything I could about the Everglades.

The cover of Amy Green's Moving Water: The Everglades and Big Sugar.

Image: Courtesy Photo

You use the lives of George and Mary Barley as a narrative thread throughout the book. Why is their story so important?

In the early '90s, George Barley was a wealthy real estate developer in Orlando. He loved to fish in Florida Bay and he could clearly see the environmental degradation that was happening down there. He kind of flew into a rage and he became this torpedo on Everglades restoration. As he learned how the problems in Florida Bay were related to problems in the Everglades, he quit his job and dedicated his life to Everglades restoration.

By '95, Barley's stature and his influence in Everglades restoration policy and politics was probably close to that of the secretary of the interior at the time. He was the first to bring real resources to Florida's environmental movement. Before that, there had been attempts at Everglades restoration that might be described as low-hanging fruit.

Barley was very politically connected, having served with government agencies, and he was able to get other individuals connected with Everglades restoration—most importantly, Paul Tudor Jones, who was his best friend and a very wealthy real estate tycoon. Jones funded Audubon's first Everglades position in South Florida. He provided the funding for The Everglades Foundation that was just getting going. And, after George's death, Jones funded most of Mary Barley's campaign for a ballot initiative that would have taxed sugar growers to raise money for Everglades restoration.

George and Mary, each in their own way, brought resources and a level of intensity and attention that the watershed hadn't really had before that.

It's been more than 20 years since Congress approved the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan. What's the current status of the project?

December was the 20-year anniversary of Everglades restoration being signed into law by former president Bill Clinton, and we got a report just a few weeks ago from the National Academy of Science, which has been tasked with providing Congress with regular reports on the progress of Everglades restoration.

It's an exciting time, because you are beginning to see construction is underway on projects and progress is being made. Everglades restoration is shifting from a time of planning to dirt actually moving.

I would say, too, for many environmental groups, it's a hopeful time because of the DeSantis administration. He has put a lot of money toward Everglades restoration and given a lot of attention to these issues. He ran for governor in 2018, during the toxic algae crisis, and that prompted him to give these issues a lot of attention. Through his connections with the Trump administration, he was able to get more money for Everglades restoration in the federal budget. It's a different time now.

How do people feel about the government paying to restore land polluted by Big Sugar?

That was the big issue that infuriated George Barley and motivated Mary Barley after his death—the idea that, as they put it, sugar growers were not paying their fair share.

You had a situation in which sugar growers were farming right in the heart of the historic Everglades. They were doing that with a water management infrastructure the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had almost literally designed for them. The water management infrastructure functioned according to sugar growers' needs and prioritized their needs over the Everglades.

It also was a time when there was federal litigation against the state over sugar growers' pollution in the Everglades. Sugar growers were not defendants in the litigation, but the litigation was about them. When the state reached a settlement, the state legislation that resulted and that launched a cleanup plan was seen as, again, not requiring sugar growers to pay their fair share toward cleanup. Sugar growers and their place in the Everglades and their role in Everglades restoration has been a very, very bitter debate.

At this point, sugar growers have gone beyond what is required of them as part of the litigation. They have initiated what are called best management practices aimed at cleaning up the Everglades water. That involves things like adjusting irrigation techniques and fertilizing techniques. Most of the water in Everglades National Park today meets the state standard for cleanliness.

However, a lot of the environmental groups would say that the measures that the sugar growers have taken are not enough, and they would add that much of the work aimed at cleaning up sugar growers' pollution and the Everglades has been paid for by taxpayers.

You're kind of seeing something similar start to bubble up again in the recent news about Piney Point, where, again, a private landowner has caused a lot of problems and there's concern that taxpayers are going to have to clean it up.

Why should people who don't live near the Everglades care about its restoration?

At the time it was signed into law, Everglades restoration was billed as the biggest environmental restoration effort in the history of the world. Today, it's still one of the most ambitious attempts at ecological restoration in the world. This is a globally significant project.

For example, one of the ways they're cleaning up the water is by building engineered wetlands across South Florida. These wetlands act as a sieve. They filter out the nutrient pollution. As the water flows through these wetlands, it flows clean. The size of these wetlands is unlike anything that has been done anywhere else in the world. And they're still building more. People come from all over the world so they can learn about these engineering techniques and to see what we're doing in Florida.

Also, the Everglades is our most important water resource. Florida is a fast-growing state and that growth is pressuring our natural resources, including our freshwater drinking supplies. That is the other goal of Everglades restoration—to preserve that drinking water supply for future generations.