The Sarasota Sea Lion Preserve Opens to the Public in Myakka City

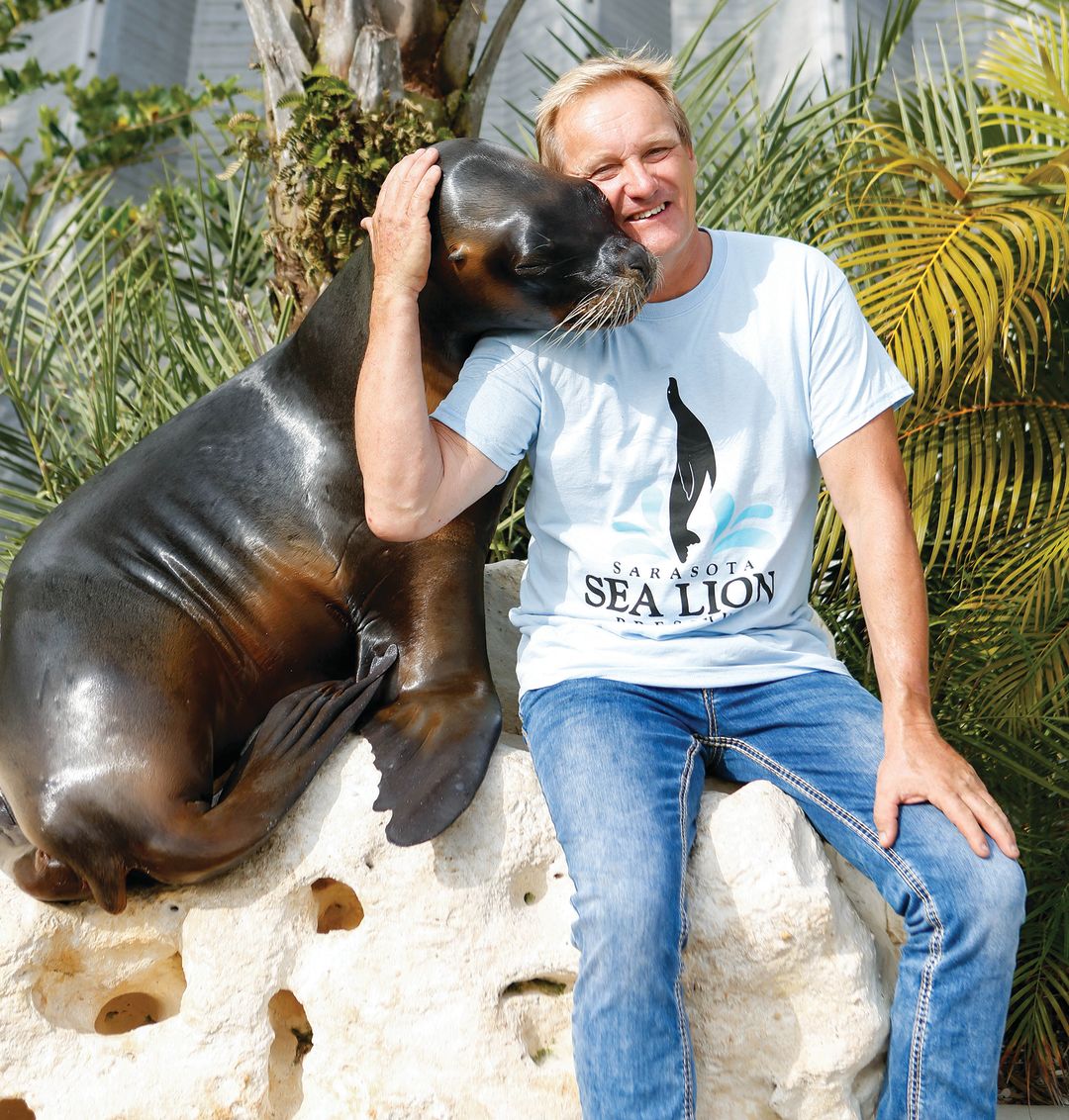

Marco Peters with a sea lion.

Image: Jennifer Soos

A sign prompts visitors to roll down their windows as they enter the Sarasota Sea Lion Preserve in Myakka City. Can you hear our sea lions? it asks. I stop and listen. A squirrel chirps up in a tree, a mockingbird trills from a nearby fencepost. But as I drive down the gravel road, I hear it in the distance—a bellowing arf like the somnolent bark of a big dog dreaming on the couch.

Nestled in some 20 acres of oak hammock just west of the Myakka River, the Sarasota Sea Lion Preserve is home to 23 sea lions from as far away as China. Some were imported from South America 17 years ago. Others have been bred on site. Many are rescues—victims of shark attacks, fishing nets and beachgoers who, by feeding the food-motivated creatures, inadvertently tame them up to the point of disabling them.

Marco Peters is the man behind the for-profit preserve. A 58-year-old Dutchman with vestiges of an accent, rough hands and a firm grip, Peters exudes an energetic passion for these wild animals. In a past life he trained big cats with his brother for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Two decades ago he made a calculated transition from real lions to sea lions.

“I was with Ringling for four years,” Peters says. “I was just getting into my mid-30s and didn’t want to wait for them to tell me they found somebody thinner, better-looking and with a better act. So, I started something new. I totally zoomed in on sea lions.”

Sea lions dive in and out of the pools on the one-acre plot currently set aside for the preserve. The captive colony includes a mix of California sea lions (slick, playful and inquisitive) and Patagonian ones (frumpy, guttural and huge). On the day I visited, the entire group—including a handful of sea lions Peters was temporarily putting up for the Columbus Zoo—consumed more than 300 pounds of assorted seafood like herring and squid.

All that grub equates to a lot of organic waste. The pool water is perpetually pumped and filtered, circulating completely five times each hour, racking up an electric bill of about $4,000 per month.

To fund the operation, Peters and his team take the sea lions to zoos, where they perform and educate visitors on marine mammal conservation. But finances have been tight, so last December Peters opened the facility up to the public. They built a small theater with space for a few dozen people and a swimming pool where guests can get in the water with some of the tamer sea lions. Peters hopes to attract birthday parties, corporate team-building events and groups looking for unique outings. Reservations range from $95 to $995.

Despite the trappings of a zoo, Peters insists he doesn’t want to be another SeaWorld. “I'd rather show guests around, so they can see the animals and interact with them,” he says. “I mean, we’ve got all of this stuff here. We need to find a way to make it run.”