Is Sarasota Changing for Good?

I was 12 years old when my parents first moved from frenetic northern Virginia, where every conversation started with, “What do you do?,” to Sarasota, which felt placid and laid-back in comparison. My parents purchased their new house, built on spec, in 2006, at the height of that era’s real estate boom. Coming from a 1970s colonial at the crest of a Virginia cul-de-sac, our sparkling home, with its cerulean tiled pool and Mediterranean roof, beckoned with the promise of a new life. But it quickly became a symbol of something else—the excesses of Sarasota’s real estate sector, which fell apart during the Great Recession, leading to countless housing projects left on hold and never completed, forever in stasis. We had moved to one version of Sarasota only to quickly find ourselves in quite another.

Almost 20 years have passed since then, and here we are again, finding ourselves entering yet another iteration of Sarasota. My parents, who moved here for the dream of warm weather and a more relaxed lifestyle, now talk of leaving. At dinner parties, I hear guests discussing the latest outrages by Gov. Ron DeSantis or the Florida Legislature in hushed tones, not to mention grumbling about all the new developments creeping in and all of the open space we’re losing. Nearly every day, a new Facebook post emerges from a disgruntled resident abandoning Sarasota for greener pastures. Who among us hasn’t heard the common refrain, “I would leave if I could”?

Of course, the number of people who are unhappy with current-day Sarasota and moving out is dwarfed by the number of people who have fallen in love with the region and are moving in. The Covid-19 pandemic encouraged many people who had toyed with the idea of moving to Florida to take the plunge, while new remote work options have allowed people to choose where they want to live rather than be bound to a particular city. Many of those people are choosing Sarasota because of its sunshine and beaches, and some are drawn by the area’s increasingly conservative politics. The result has been a boom in new condo buildings downtown and new suburban developments in places that had previously been mostly untouched—changes that many longtime residents decry.

Downtown Sarasota's increasingly crowded skyline.

Image: Everett Dennison

But is Sarasota really changing all that much? Haven’t growth and development always been controversial? For decades, people have complained about losing the Sarasota they love, the one they encountered the day they arrived, whether that was in the 1970s or last week. But in conversations with local activists, academics and politicians, a common refrain emerges: Sarasota really is changing this time, and our shifting identity has led to an uptick in tension and discord. Explanations range from local government’s increasingly unchecked mentality toward development, the region’s changing political demographics and a general air of social change, which is harder to pin down but felt by many.

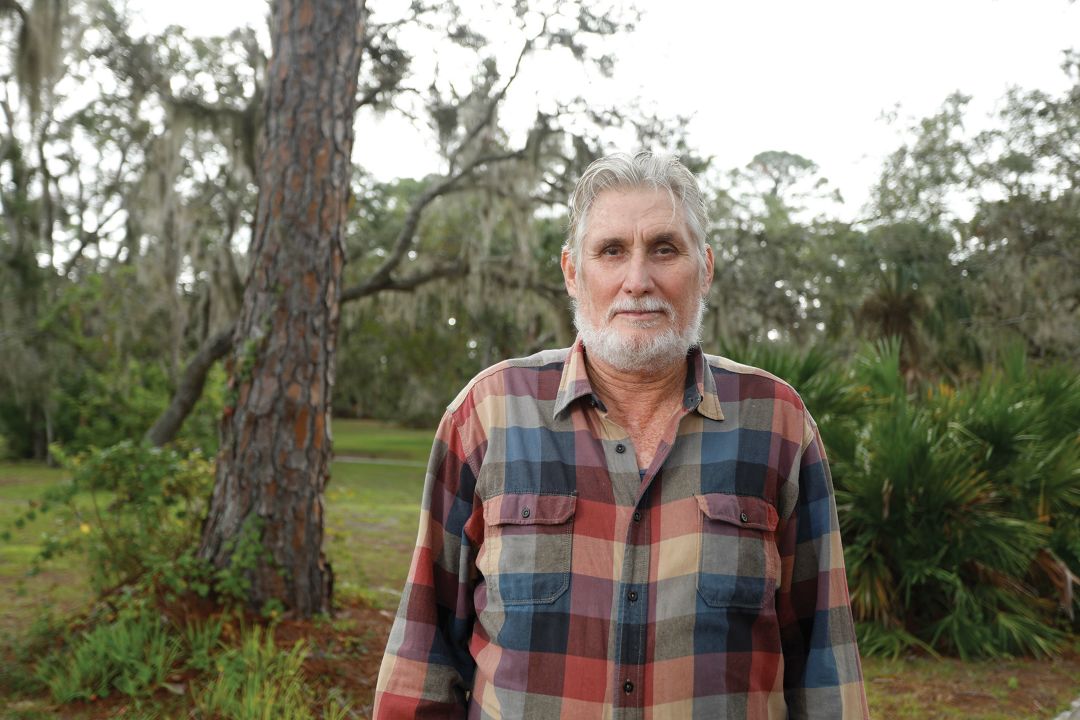

Jon Thaxton

Image: Salvator Brancifort

Some longtime local observers, like Sarasota native Jon Thaxton, a former county commissioner who is now the senior vice president for community leadership at the Gulf Coast Community Foundation, say tensions are higher today than ever before. “I can safely say that the hostility in the political environment, both local, regional, state and national, is like nothing I’ve ever seen,” Thaxton says.

A new neighborhood under construction in Lakewood Ranch.

Image: Everett Dennison

It may seem strange to begin the history of the new Sarasota with the coming of Lakewood Ranch, but that is perhaps the development that has had the largest single impact on the region’s growth in the last 25 years.

Lakewood Ranch sprouted nearly 30 years ago from 48 square miles of land that was Schroeder-Manatee Ranch east of I-75. The community’s first model homes and “village” opened in 1995. At the time, prices began in the high $80,000s, a number that is unthinkable now. By 2020, the planned community was home to almost 18,000 homes on more than 33,000 acres, and in January 2023, Lakewood Ranch was recognized as “the best-selling, master-planned multi-generational community” in the country, having sold 1,846 new homes in 2022, down from 2021’s record-breaking number of more than 2,500 new homes sold.

That nearly exponential growth proved to be an inspiration for others, who watched Lakewood Ranch developers turn what were once largely cow pastures into a thriving community that has attracted more than 60,000 residents. Suddenly, parts of Sarasota and Manatee counties once seen as unsuitable to development became fair game.

“Back then, University Parkway was a long, dusty shell road,” Robin Uihlein, a member of the family that owned Schroeder-Manatee Ranch, said of the Sarasota Polo Club in 2010, according to an article in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune. “We would hold events like the Ringling Cup and some big charity events, and it was pretty incredible to watch Mary Fran Carroll [the former chief executive officer of Schroeder-Manatee Ranch] get people to come out here. They’d scoff and say, ‘Come on, there’s nothing east of the interstate!’ And she’d say, ‘Oh, yes, there is. Trust me!’”

The emergence of Lakewood Ranch kicked Sarasota County officials into gear. If the community was a harbinger of things to come, then they had better have a plan of their own. Thus was born Sarasota 2050, a comprehensive long-range planning document adopted in 2002 and intended to guide the development of eastern Sarasota County for decades to come.

Sarasota County was created roughly 100 years ago—in July 1921, when it became its own entity, separate from Manatee County. The first official Sarasota County census in 1930 showed a population of 12,440 residents. By 1950, the number of residents had more than doubled, to almost 29,000. A post-World War II boom from 1951 to 1960 caused the population to more than double once again, this time to more than 75,000. That unparalleled growth only continued, with the county’s largest influx of new residents—more than 80,000—coming in the 1970s. The boom coincided with the development of the Tampa-to-Naples portion of I-75, which was finished in Sarasota County in the 1980s and opened up the eastern part of the region to more habitation.

In the early 2000s, Sarasota fully embraced the real estate boom. From 2000 to 2005, the county’s population grew by 12 percent and the median sales price for a single family home increased by a whopping 92 percent. This onset of demand prompted county officials to get creative: How could they ensure that there would be enough housing for people who wanted to move to Sarasota while also preserving the region’s environment and open land? Their answer was Sarasota 2050, which was intended to provide “the option for higher density developments in rural/semi-rural lands out east in exchange for preservation of open space and greenways,” according to the county’s Planning and Development Services department. Wrapped up in the plan was the definition of the urban service boundary, which separates dense development from agricultural land.

Thaxton was one of the county commissioners involved in the adoption of 2050. At the time, he says, it was “one of the most progressive” future land-use plans out there. In 2003, it even won a charter award from the Congress for the New Urbanism and was praised for its environmental stewardship and encouragement of compact development. The idea, Thaxton says, was to “draw a line in the sand”—a term that was used often, he notes—between urban development and development that would retain open space and the character of rural Florida.

On the day the document was signed, Thaxton says, commissioners opened a bottle of Champagne in the back room and toasted what they saw as a victory for smart growth.

“We believed it to be a successful community dialogue and compromise plan that would secure the preservation of eastern Sarasota County while allowing for some additional growth,” Thaxton says. Today, he regrets voting for it. “It was the worst decision I made as a county commissioner,” he says. Part of that has to do not with the 2050 plan itself, but with the fact that, as Thaxton says, “all of the commitments” in the original plan have either been “compromised or eviscerated.”

“We are fast approaching the point in Sarasota County where these planning decisions will have no impact on preserving natural landscapes,” Thaxton says, “because the [natural landscapes] will all either be gone or protected.”

Joe Gruters

Image: Salvator Brancifort

State Sen. Joe Gruters, who has been part of the Florida Legislature since 2016 and served as chairman of the Republican Party of Sarasota County for many years, attributes the destruction of the 2050 plan to one thing: term limits. In 1998, Sarasota County voters passed a referendum implementing a limit of two four-year terms for county commissioners, but that measure didn’t go into effect until 2012 because of a drawn-out legal battle. (Thaxton himself was forced to leave the county commission that year because of term limits.)

“When you have elected officials who are in office for long periods of time, they can win or lose without support from any particular group,” Gruters says. “Now people are campaigning for the county commission ahead of time. We had the 2050 plan, we had the urban service boundary line, and when you flush out all those old county commissioners, all the restrictions that existed are gone.”

Freed from the 2050 regulations, county commissioners can now do as they wish—or, as some might say, as developers wish. In the last 10 years, the county has greenlit developments that, critics say, threaten to change the character of the region. From future residences on what was once rural Hi Hat Ranch to continued building east of I-75 on Fruitville Road, the proposed communities are often gated and isolated, forcing residents to commute by car and increasing the amount of traffic on formerly quiet roads.

But in recent years, the county’s disregard for tempering any development has led to pushback. In 2020, Old Miakka activist Becky Ayech rallied a group to fight a proposed 400-home community on roughly 400 acres of land off of Fruitville Road. (She lost.) Siesta Key residents, meanwhile, are leading a push to incorporate the barrier island as its own municipality after a series of proposed hotel developments and a litany of decisions they say are at odds with their vision for the future of the island. (Activist Lourdes Ramirez recently successfully challenged the county’s approval of a 170-room, eight-story hotel on Siesta Key, noting that it would violate the county’s comprehensive plan.) Residents are starting to push back—but is it too little, too late?

Frank Alcock

Image: Salvatore Brancifort

Political experts like Frank Alcock, a professor of political science at New College of Florida who ran for state Senate in 2016, say that what once was impossible now no longer is.

“My take is that a lot of the guardrails have come off,” Alcock says. “Whether it’s the internal calculus of the representatives around the state or in our area, we’ve seen a shift on a number of issues. There’s not much resistance to rapid development.”

Thaxton is at work on a sweeping project: He aims to map all of the lands in Sarasota County that have been developed, are in the process of being developed or will be “imminently” developed, and look at what’s left. It’s a question, he says, to which nobody knows the answer.

“People say, ‘We’re not going to let Sarasota become Fort Lauderdale and pave over the entire county,’” he says. “Well, I’ve got news for you—we are there. We’re not there in the built environment, but we are there in the planned environment.”

What that means, according to Thaxton, is that enough development rights have already been given away in Sarasota to double the county’s existing population. He understands why some people have given up the fight to preserve Sarasota’s open land and quiet character, but, he says, to accept that nothing can be done to alter our current reality is to let the other side win.

“If you’re here and throwing in the towel, your complacency is now a tool of compliance for the other side,” Thaxton says. “And that’s game over.”

The Hollow, in Venice

Image: Mark Peterson/Redux

The people moving into all those new homes and condos are also changing our region’s political makeup. In September 2022, 43.5 percent of Sarasota voters—152,959 people—were registered Republicans and 28.9 percent—or 101,418—were registered Democrats. Almost a year later, that number increased to 44.1 percent registered Republicans (155,081 voters) and 27.9 percent registered Democrats (98,078). The picture becomes more striking when we look at the change from the end of 2018, shortly after Gov. Ron DeSantis’ first election, to July 2023. In that time period, the number of registered Republican voters in the county increased by almost 18,000; by contrast, the number of registered Democrats fell by more than 1,000.

Sarasota’s increasingly red composition is both a reflection of the larger microcosm that is Florida and a microcosm itself. The area has become a breeding ground for many of Florida’s most controversial figures and policies. Many of the far right’s most incendiary leaders, like Trump administration national security adviser Michael Flynn and erstwhile White House chief strategist Steve Bannon, have connections to the region. The former even tried to remove Republican Party of Sarasota County chairman Jack Brill from the local party’s executive committee. Meanwhile, the Venice venue The Hollow, bedecked in Founding Father quotes and host to a nearby shooting range, has become a prominent meeting place for increasingly farther-right conservatives who want a place to espouse their ideals. At the same time, in late 2022, three people were elected to the Sarasota County Public Hospital Board who vehemently questioned the necessity—and safety—of vaccines against Covid-19. As a result, the Sarasota area has been the subject of multiple national news stories in recent years, highlighted in outlets like The Washington Post, The New York Times and Vanity Fair and featured in segments on PBS and NPR.

Gruters argues that “DeSantis did a great job with Covid-19 and we became the beacon and the light of freedom,” which has made the area attractive to Republican voters. “Based on Covid-19, based on education, people are fleeing some of these other states,” he says. “From an electability standpoint, it hurts those states for conservatives and it helps conservatives in Florida.”

Alcock says it’s difficult to parse the exact origin of the area’s changing politics. “Are demographic changes causing the politics to change or vice versa?” he asks. “I think it’s actually a self-reinforcing circle. The Republican party under the Trump administration began to change and become much more populist and, in the wake of the Trump presidency, Biden has come in. The culture war has really just come to the forefront.”

Vickie Oldham

Image: BARBARA BANKS

Of course, one’s view of Sarasota’s changing politics depends on one’s perspective. Vickie Oldham is a Newtown native and the president and chief executive officer of the Sarasota African American Cultural Coalition, which is in the process of opening the area’s first free-standing Black arts, culture and history center. She says today’s conflicts aren’t all that different from those of previous generations.

“When you’re dealing with the history of African Americans and their existence in Sarasota, it’s really hard to see any change,” she says. “Because, for African Americans, this has not been, as the poem says, a crystal stair—it has been an uphill struggle and a battle for equity, inclusion and diversity throughout their existence. That’s still the case.”

Oldham says she has been able to unite people from both sides of the aisle around the cause of Black history, and doesn’t believe that political differences are set in stone. “People cross over and support the initiatives they want to support,” she says. “I am going to refuse the hype that things are so partisan that no changes can happen. If I bought into that, I would never be doing what I’m doing.”

Still, local officials like Gruters and Christian and Bridget Ziegler have helped to pioneer some of the state’s most polarizing legislation. Christian Ziegler is a former county commissioner and the former chair of the Republican Party of Florida, and Bridget Ziegler is a School Board member. In 2018, Bridget worked to co-create state legislation that would come to be known as the Florida Parents’ Bill of Rights, which stipulated that “it is a fundamental right of parents to direct the upbringing, education and care of their minor children.” In many ways, this would become a precursor to 2022’s Parental Rights in Education law (dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” law by opponents), which banned classroom instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity in kindergarten through third grade or “in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” It also gave parents the ability to challenge any school district they saw as not adhering to the policy. (A 2023 amendment to the legislation extended this ban to all grades, unless “expressly required by state academic standards" or as "part of a reproductive health course or health lesson for which a student’s parent has the option to have his or her student not attend.”)

Christian Ziegler

Image: Mark Peterson/Redux

Bridget Ziegler

Image: Mark Peterson/Redux

Bridget Ziegler claimed in an online bio that the Parents’ Bill of Rights helped pave the way for DeSantis’ executive order prohibiting Florida school districts from implementing mask mandates. She also worked to create Moms for Liberty, a grassroots organization “fighting for the survival of America by unifying, educating and empowering parents to defend their parental rights at all levels of government.” The conservative group now has more than 100,000 members in 45 states. Bridget also served as the vice president of school board leadership programs for the Leadership Institute, an organization that was founded with the goal of teaching conservatives “of all ages” how to excel in “politics, government and the media,” per its website. In August 2023, the organization opened a School Board Training headquarters on Main Street in Sarasota, with a banner reading, “Training conservatives since 1979."

Bridget Ziegler, who did not respond to a request for comment for this story, resigned from her position at the Leadership Institute last month, amid news that Christian Ziegler is being investigated by the Sarasota Police Department for allegedly committing sexual battery last October, an allegation he has denied. Christian was removed from his post with the Republican Party of Florida after news of the investigation surfaced, and is also reportedly being investigated for the crime of video vouyerism. Bridget has faced pressure to resign from the Sarasota County School Board since the investigation was revealed.

Gruters, meanwhile, has been one of the leading forces behind Florida becoming Trump territory. It was Gruters who was the Florida co-chair of the former president’s first campaign, and it was also Gruters who led unsuccessful attempts early in his time as a state senator to restrict access to abortion. Those efforts may have failed at first, but in 2023, in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, the Florida Legislature voted to ban most abortions at six weeks.

Rhana Bazzini

Image: Salvator Brancifort

Sarasota has been a conservative political region for decades, but for people like longtime public education and democracy activist Rhana Bazzini, who has lived in Sarasota in some form since the late 1970s, our politics have shifted dramatically to the right. Not too long ago, in the late 2000s, a Republican like Nora Patterson could serve on the Sarasota County Commission after also serving as the board chair for Planned Parenthood of Southwest and Central Florida. That’s unthinkable today.

“What has happened to Sarasota County is that we have gone totally insane,” Bazzini says. “Florida is crazy, and Sarasota is central crazy.” Bazzini, 90, says that several of her neighbors have moved out of the region because of politics and she herself has given up on the idea of the state addressing climate change and other pressing crises.

“If I weren’t as old as I am and my only blood relatives were not in Englewood, I would be out of here in a nanosecond,” says Bazzini.

Conservative leaders like Christian Ziegler have taken issue with the way Democrats have depicted the state’s politics. In a 2022 interview with The Washington Post, Ziegler praised DeSantis as the “No. 1 threat” to those who “want to crack down on freedom and … fundamentally change the country into some sort of socialist utopia.”

“And because of that,” he said, “they are dead set on branding Florida as some sort of extremist state.”

Some people might ask: Isn’t it? Ziegler said in a February 2023 interview with an Orlando NBC news affiliate that “until we get every Democrat out of office and no Democrat considers running for office, we’re going to continue to step on the gas and move forward in Florida.” In a post on X, formerly known as Twitter, Ziegler wrote, “The work is not done until there are no more Democrats in Florida.”

As an example of extremism, one could point to New College of Florida, which is in the midst of an overhaul initiated by DeSantis, who appointed seven new members to its board of trustees last year and promptly announced his intent to transform the state’s honors college from a progressive bedrock to the "Hillsdale of the South," according to a statement from education commissioner Manny Diaz. All of this was at odds with the desires of the vast majority of the school’s staff and, perhaps more importantly, students, who fled in droves.

It’s not just New College. Alcock says he is hearing from all over Florida that universities outside the state are seeing a large number of job applicants from Florida who are willing to take pay cuts and a lower status just to get out.

“DeSantis taking over the board at New College is new—nobody will contest that,” says Alcock. “It’s a point of pride for the new leadership and the governor that nobody has done this before. It’s a test case. What’s happening here is emblematic of things that are happening around the country, but the visibility of what’s happening in our own community is unmistakable.”

A gap between what residents want and what they get has become common in Sarasota politics. In 2022, Sarasota County commissioners asked voters to decide once again whether they really wanted single-member districts. In 2018, nearly 60 percent of voters approved them, but, four years later, commissioners argued that voters maybe didn’t understand what they had agreed to. A new vote turned back roughly the same results: 57.2 percent once again approved single-member districts. The entire debacle reeked of a certain underlying condescension: We know better than you.

Around the same time, Sarasota County School Board members also revealed their ability to do just as they pleased. A 2022 meeting that should have simply seen the installation of two new members turned into the beginning of the end for then-superintendent Brennan Asplen. At that meeting, School Board member Karen Rose called for a special meeting to recommend the termination of Asplen’s contract.

It took only a week for the board to begin the process of severing its relationship with Asplen. By the date of Asplen’s last meeting, Bazzini says, the community’s mood was somber.

“There were so many people that they couldn’t even fit inside,” she says. “When [Asplen] got up to leave, he walked among us and shook our hands and we all gave him a standing ovation. Some of us were crying. The only good thing I can say is: That was when people who weren’t paying attention started paying attention.”

Of course, the story of intensifying political conflict isn’t unique to Sarasota. Far from it. There has been a marked social change both in national and local politics that has left hostility where once there was none. You can see that in clips of people screaming at School Board meetings that go viral, as well as hateful statements about LGBTQ+ people and other groups. Many describe a general sense of unease—the feeling that, at any moment, a disagreement could erupt into a confrontation.

Oldham says she has not experienced an increase in everyday hostility (“I can’t really say that I feel that,” she says), but she says she does fear for her safety. Last August, three Black people were shot and killed at a Dollar General in Jacksonville in a shooting in which victims were targeted because of their race. It’s another in a spate of racist shootings that have plagued the United States, often perpetrated by young white supremacists. And it’s caused Oldham to have second thoughts about her walks through her neighborhood or a trip to Macy’s or Barnes & Noble.

“The thought of walking around being a target is frightening some days,” she says. “Do I want to walk around my neighborhood? It’s a diverse neighborhood, but I’m wondering whether there are any hatemongers who might not want me to live here. It’s the tip of the iceberg compared to what my ancestors dealt with—hanging from a tree, being set on fire. I’m just dealing with perceived terror.”

Both Alcock and Thaxton, who are accustomed to dealing with community members from both sides of the aisle, note a marked change in these interactions in recent years. Since 2006, Alcock has played a sort of mediator role at local political events, like at Sarasota Tiger Bay Club gatherings and other community panels. It used to be, he says, that prominent Republicans and Democrats could go out to dinner and discuss their differences with a “baseline of common respect and common knowledge.”

“That’s gone,” he says. “Those conversations are just much more difficult because we are living in different realities. I think there’s just a lot more animosity and tension.”

Thaxton echoes that, recalling how he was once able to organize a panel with some of the state’s strongest Republican and Democratic leaders, unleash a spirited debate and then end the conversation with a sort of truce.

“I don’t see that today,” he says. “That is the political climate that I yearn for—where we can take two Florida leaders, put them on the same stage, let them have a battle royale and then a reconciliation. That process is what advances the American way.”

From Gruters’ perspective, it’s not so much social relations that have changed as it is the voters. In the early 2000s, when Republicans would poll various precincts to see what percentage of voters might swing for their candidate, the percentages were significant. But by the 2020 and 2022 elections, Gruters says, there were few swing voters left.

“The voters are no longer open to different parties,” Gruters says. “People may say they are, but in the end, they’re not.” Still, Gruters says, he has conversations with Democrats “all the time.” He argues that Sarasota is “a center-right community” and that his voting record reflects that. (Others likely disagree with that assessment.) “But,” he says, “I’m always happy to have conversations with my colleagues in the Senate and here in Sarasota.”

Much like Sarasota was when my parents first moved here, the city is at an inflection point, and none of us know exactly which way it will go. Will all the people moving here find the conservative, suburban paradise they envision? Or are they destined to join the ranks of those who come to Sarasota because they fell in love with the region, only to find the city changing around them? Sarasota’s identity has always been in flux, and it always will be. The danger is that, in trying to create something new, we destroy the very things—the green space, the peaceful lifestyle, the strong sense of community—that drew us here in the first place.