Sarasota’s Climate Adaptation Center Updates Its 2021 Hurricane Forecast

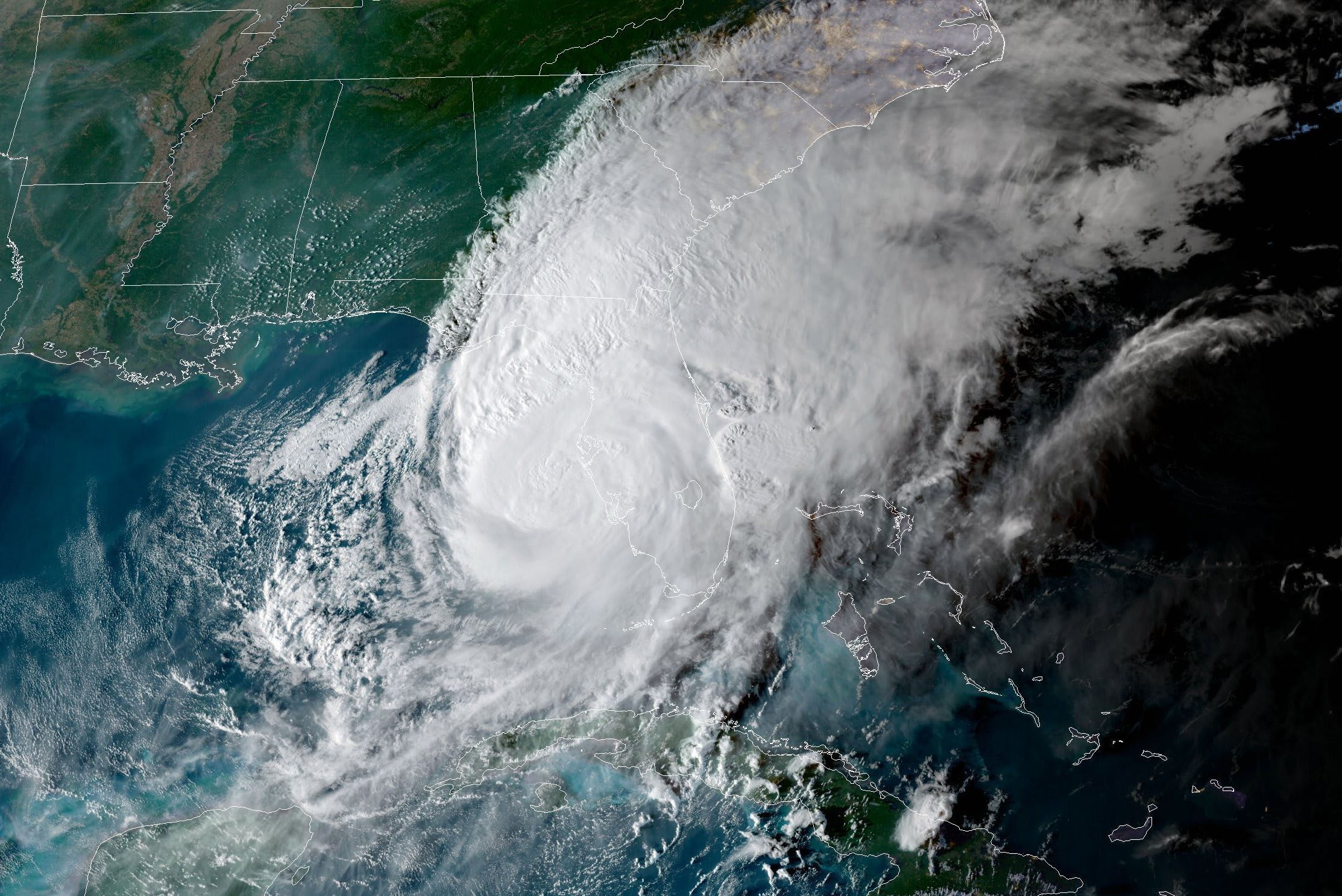

2017's Hurricane Irma.

Peak hurricane season is almost here, which means it’s time to take another look at the 2021 forecast. The most severe or major storms typically occur from late August into November, with a peak around Sept. 10, and a second peak in early October, the most dangerous time for storms along Florida’s west coast.

We forecast 20 named storms for 2021 this past April. After a record season in 2020, with 30 storms and four Category 4 storms, this season may seem meek in comparison, but, if you are feeling that way, let me try to change your perspective.

Thus far in 2021, Ana, Bill, Claudette, Danny, Elsa, Fred and now Grace have formed. Hurricane Elsa was the earliest fifth storm in history. Grace, our seventh storm, which is not expected to affect Florida, is early historically, but isn’t the earliest seventh storm on record. It’s a very active season, but not quite as active as 2020.

Going forward, I am looking at three major factors, the absence or presence of La Niña, sea surface temperatures (SSTs) and the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), discovered by two of my National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) colleagues when I was practicing my own science at the center.

Let’s start with the MJO. While the entire system is large and eastward moving, half of the MJO is a low-pressure area with rising motion that promotes storm formation. The other half is a high-pressure system with sinking air motion that promotes good weather. When the low-pressure part of the MJO is over the Atlantic Basin in peak storm season, it increases the number of hurricanes forming.

Next, and perhaps the most important factor, are SSTs. Hurricanes feed off warm seawater energy content and covert that energy into wind and rain.

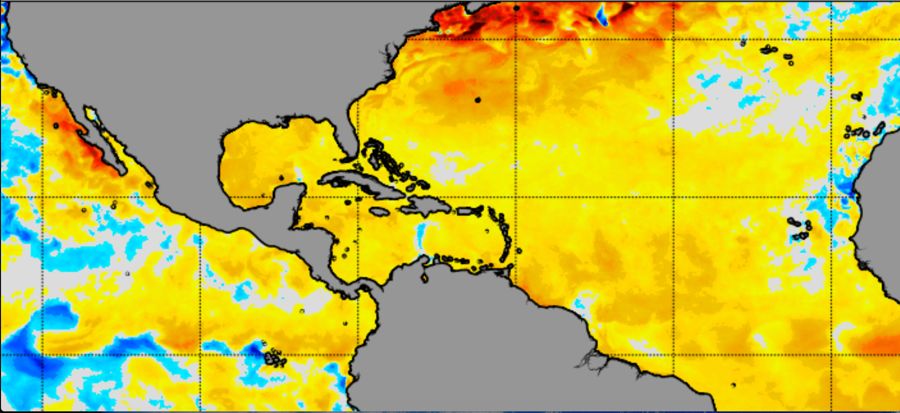

Image: Courtesy Photo

In the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) image above, the dark gray areas are the landmasses, and the colors are the sea surface temperature anomalies from cool (blue, below normal) to red (much above normal).

The SSTs in the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean and tropical Atlantic are above normal almost everywhere. This is a plus for hurricane formation.

Note, too, the red areas along the northeast coast of the U.S. Should a storm move up the coast, the much warmer-than-normal ocean temperatures will keep that storm stronger for longer. The risk for a storm along the east coast and the risk for a major hurricane are therefore enhanced.

With both SSTs and the MJO in patterns that favor more hurricanes and more intense storms, the third piece is La Niña.

When La Niña occurs, the SSTs in the mid-Pacific Ocean are colder than normal, and that means wind shear in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico tends to decrease. NOAA models show that the ocean water in the mid-Pacific area is forecast to cool. If it does, a La Niña event will be underway. The main takeaway is that a La Niña event is about to happen during peak hurricane season.

With all three major indicators flashing red at this time, the original forecast of 20 named storms, up to 10 hurricanes and three to five major hurricanes, seems on the mark.

One final caution: May was a drought month in Florida. There is a high correlation between dry months in May and major hurricanes in South Florida during peak season. In 1992, Hurricane Andrew, a Category 5, demolished parts of South Florida after a very dry May and during a below-normal hurricane season. With a very active peak hurricane season in the offing, this should be an extra diligent time for South Floridians.

For the west coast of Florida, we will likely see more visits from nature’s most destructive storms. In a climate-warmed world, extreme climate events are becoming more frequent. While early season storms have been weak, that trend will likely be broken by a series of stronger hurricanes in the weeks and months ahead. To stay ahead of the storms, please visit the Climate Adaptation Center website for information and updates that will help keep you safe.

Atmospheric scientist Bob Bunting is the chief executive officer of Sarasota’s Climate Adaptation Center.