Longtime Republican Representative Tom Rooney Was a Popular and Experienced Politician. Then He Decided to Leave Washington.

On the morning of June 14 last year at a park across the Potomac River from the nation’s capital, Congressman Tom Rooney was practicing with his fellow Republicans in preparation for the next day’s annual charity baseball game against a team of Democrats. Rooney’s wife usually drove their children to school, but this day it fell to him, and he excused himself early from practice. Unknown to Rooney, a troubled 66-year-old Illinois man named James Hodgkinson, armed with a Soviet-style semi-automatic rifle and a pistol, was staking out a spot behind the third-base dugout.

Rooney, who represents Florida’s 17th Congressional District, which includes the southern half of Sarasota County, left practice at 7:05 a.m. He never heard the flurry of gunfire that came just four minutes later, critically injuring Congressman Steve Scalise of Louisiana, the House Majority Whip, and three others, before police shot Hodgkinson, who died later that morning. Rooney was oblivious until his scheduler called his cell phone.

“She said, ‘Please tell me you didn’t go to baseball practice this morning,’” Rooney recalls. “I told her I did but I was in the car now, taking my boys to school. She said, ‘You need to turn on the radio.’ I did not take off my baseball uniform all day. I tried to do a couple of interviews, but could not get through them. I play first base, directly across the field from where the shooter was positioned. And I stood out because I’m a big guy. I would have been an obvious target.”

The sheer madness of a man coming to a baseball practice intent on murdering people because they were Republicans deeply affected Rooney. “Not a day has gone by that I have not thought about it,” he says. And it became a factor, one of several, in his announcement in February that he would not seek re-election. In doing so, Rooney has become part of the biggest wave of Congressional departures in more than a quarter-century. Through early April, 43 Republicans either announced their retirement from Congress, their intention to seek another office or have been forced out, nearly double the average of both political parties in a normal year.

Rooney’s 2013 swearing in with his family and former House Speaker John Boehner.

The turnover has been attributed largely to an expected Democrat surge this November that threatens to end Republican control of the House and, potentially, the Senate. But Rooney, 47, belies that explanation. He easily won his five previous elections, getting nearly 62 percent of the vote in 2016, and three major forecasting groups rate the district safely Republican. Moreover, with a decade in the House, Rooney was set to be rewarded for his longevity and experience with the chairmanship of a subcommittee of the coveted House Appropriations Committee.

Anders Crenshaw, a former Republican Congressman who represented the Jacksonville area from 2001 to 2017, says Rooney’s decision not to seek re-election is a significant loss for Florida, which traditionally has been under-represented relative to its size on important committees such as Appropriations.

“From Day 1 you could see that Tom was a rising star,” says Crenshaw. “He doesn’t talk all the time. He also listens. And he understands that just because some people have a different view, it doesn’t make them your enemy. His decision reflects what has been happening. The left is moving further to the left and the right is moving farther right and those in the middle are leaving.”

One area, in particular, where Rooney’s departure is being felt is the citrus industry, says Mike Sparks, CEO of Florida Citrus Mutual, the state’s largest citrus growers organization. “He was the only Florida representative on the agricultural subcommittee of the Appropriations Committee, which is a vitally important role.”

The congressman on horseback during a parade in Arcadia

Rooney led the effort to get $125 million over five years for research to combat citrus greening, which has been devastating Florida’s trees. Rooney also was pivotal in securing funding for Florida’s farmers in last year’s $2.3 billion hurricane relief bill. “Florida agriculture suffered $760 million in losses from Hurricane Irma,” Sparks says. “Without Tom Rooney, I don’t know if we would have gotten any help. It’s shocking that he’s leaving.”

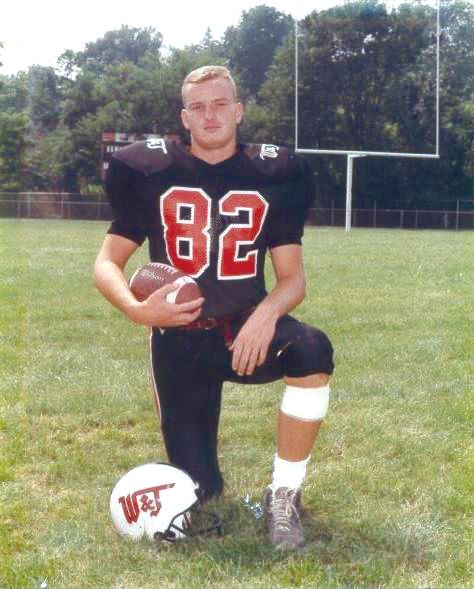

Rooney at college as a football player

Rooney hails from famous lineage. His grandfather, Art Rooney, was a cornerstone of the National Football League, the founding owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers and a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. A football player himself—he played on Syracuse University’s 1989 Peach Bowl-winning team—Tom Rooney went on to become a lawyer, joined the Army as a member of the Judge Advocate General’s Corps (JAG) and later became CEO of a home for abused and abandoned children in Palm Beach.

In 2008, in his first run for elected office, he defeated Democrat Tim Mahoney to win what was then Florida’s 16th District. After redistricting in 2012 created the 17th District, Rooney moved from Palm Beach County to Okeechobee, won three times and seemed to have established a base of support that would keep him in office for years to come. But increasingly the job became distant from what he idealized.

“I’m not very good at fund raising and retail politics,” Rooney says. “What I think I am pretty good at is getting in the weeds and trying to solve problems for my constituents. Unfortunately, that’s become very hard to do today with what Congress has become.”

In 2011, former House Speaker John Boehner led an effort to ban earmarks, which traditionally were used by Congress members to send money to special projects back home. Earmarks had come to symbolize wasteful spending and pet projects. But Rooney contends what may have sounded like a good idea at the time has blocked leaders from serving the needs of their districts. Instead of Rooney being able to get funding to repair erosion on Manasota Key, for example, that spending discretion has shifted to the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers.

“I’m not for private earmarks to benefit my buddies back home, but I am for returning public earmarks to allow me to do the job I was elected for,” he says. “Nobody in Idaho gives a crap about erosion on Manasota Key, but for the people who live there it’s vitally important. As a member of the Appropriations Committee, you used to have the power to help people in your communities. Now, we’ve ceded all that power to the executive branch because we can’t use earmarks, and it’s really bad for our democracy.”

Compounding the problem, he says, are think tanks and other outside political groups that score representatives on their votes. “I’ve heard from people in my district, ‘Why can’t you be more like Congressman X who has a 100 percent rating from the Heritage Action for America?’” Rooney laments. “It leaves me dumbfounded because I’ve never heard Congressman X make a single argument on the House floor or propose a single piece of legislation. For these think tanks, it means not just going against Nancy Pelosi, it means you’ve got to stick it to Paul Ryan.”

One example is guns. Even though Rooney is a gun owner and supporter of the Second Amendment, he says that even proposing “reasonable” regulations such as raising the age to buy assault rifles to 21 is condemned by the NRA. “The problem is with the political arm of the NRA,” he says. “I don’t know in the last 10 years whether there has been any compromise with guns by the NRA.”

Part of the problem, Rooney says, is that at a time when the Republican Party controls the White House and both houses of Congress for only the second time in the past 70 years, the party sometimes seems at war with itself. He’s heard Republican candidates say that former presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush were not conservative enough.

“We’re in control, but we’re fractured,” Rooney says. “I can’t understand some of what gets said. If Reagan and Bush aren’t what our team is supposed to be about, then I don’t know what team I am supposed to be playing for anymore.”

Rooney is a member of the House Intelligence Committee, which investigated Russian involvement in the 2016 election and whether there was collusion with the Trump campaign. Rooney was widely quoted as saying that investigation “went off the rails.” The Intelligence Committee “used to be a sacred cow, a highly coveted assignment,” he says. “Now, it’s just become a vehicle for members to get famous on television.” For example, when former presidential assistant Hope Hicks testified behind closed doors that she had told “white lies” on behalf of the president, committee members were leaking during the testimony. “How bad was that?” Rooney asks.

Rooney says both sides are guilty in this investigation. If you can’t be good on a committee that is supposed to put national security above partisanship, “it’s a sad reflection of the institution,” he says.

As for Trump, Rooney tries to see past the president’s combative tweets and judge his actions. It’s a task made easier because Rooney ignores social media and cable news and gets his news primarily by reading multiple newspapers every day, including Florida papers. “Social media has made our country worse,” he says. “I have never tweeted, and if I had a magic wand and could get rid of Facebook, that’s something I’d do. Go to dinner with your wife and kids and tell me there’s not a moment when everyone is looking down at their cell phones.”

Rooney supports some of what Trump has done, including his pick for the Supreme Court, signing the massive tax cut and opening talks with North Korea. But he opposes Trump’s push for tariffs, which he says will badly hurt American farmers. “When you promise people in Pittsburgh that the steel mills are going to reopen, that’s not going to happen,” says Rooney, whose family is still strongly tied to that city. “Those steel mills have become running trails. Pittsburgh is not a steel town anymore, but it has become an even better city. You can breathe the air.”

Rooney has not decided on his next career move, but he relishes the chance, after a decade in Washington, to spend time with his family and watch one of his sons play high school football.

“I got an invitation from a high school football coach to coach the offensive line,” he says. “I told my wife that’s the best offer I’ve had in a long time.”

Who's Next?

Five candidates are running to succeed U.S. Rep. Tom Rooney in Florida’s 17th Congressional District, which includes the southern half of Sarasota County: from left three Republicans, state Sen. Greg Steube of Sarasota and state Rep. Julio Gonzalez of Venice, and Bill Akins; and two Democrats, April Freeman and Bill Pollard. The primary is Aug. 28 and the general election Nov. 6.