A Taste of Haiti

I never really got to know my grandmother. She and my grandfather lived in Haiti, where my mother grew up and lived until she married my father, a journalist who was originally from New Zealand. They were forced to leave Haiti in 1963, and our family did not return for a visit until 1971, when I was 7. We stayed at my grandparent’s house in Freres, a semi-rural area outside Port-au-Prince.

My grandfather spoke a little English, and he spent some time with my brother and sister and me, helping us build cages for the chickens he allowed us to raise and slaughter. But my grandmother, Maria Bezelais—we children called her “Mamish”—spoke only French and Creole, and was a distant figure, someone who existed in the faraway reality of the grownups. My clearest memory of her, the one that pops into my brain like a faded Polaroid, is of her wearing a one-piece cotton dress, sitting at the square table in the center of her small kitchen, snapping peas or dicing garlic or cleaning djon-djon, Haiti’s tiny, aromatic wild mushrooms. I can almost hear the tinny sound of a transistor radio tuned to a local talk show that filled the room while her cook worked over the stove and a maid washed vegetables in the sink. The place smelled of rice and cloves and cumin.

Mamish was of old Haitian stock, a descendant of a mulatto general who fought for independence alongside Haiti’s first president, the despotic Jean-Jacques Dessalines. My mother tells me she had a reputation as a wise woman who was fair and nonjudgmental. She had friends from every social class, from the local peasants and wealthy neighbors to the local voodoo priest. In the 1940s and ’50s, when she owned a grocery store in Port-au-Prince and prepared food for take-out, Haiti’s president at the time, Dumarsais Estimé, was a fan of her sandwiches.

In Freres, the back door of her kitchen was always open, and neighbors often stopped by to discuss their problems and ask for advice, their children playing in the dirt while chickens scratched and pecked for feed. But more than I remember Mamish, I remember her cooking. She had a gift for the Creole cuisine that blended French and African flavors. I quickly learned to love her food.

At lunch, the table was always dressed up with a fancy tablecloth, ceramic plates, two forks per setting and a spoon for dessert. The maid worked her way around the table, serving braised chicken or goat in a brown Creole sauce or the traditional griyo—bits of marinated and fried pork—along with

mayi moulen, a coarse boiled ground corn, or French fries or boiled plantains. The meal was a festival of textures and spice, tamed by the accompanying white rice and sos pwa, a puréed bean sauce. I devoured it all greedily, but all through the meal, I held on to the hope that once the dishes were cleared, one of the maids would waltz in carrying a large Pyrex dish holding Mamish’s legendary blan mange.

To me, blan mange was the jewel of Mamish’s extensive cooking repertoire. A traditional Haitian dessert, it’s seemingly simple: coconut and milk. But it was a labor-intensive dish, taking hours to prepare. It was a bright-white, pudding-like creation that tasted gloriously of fresh coconut, from the quivering custard-like gelatin to the toasted coconut shavings on top.

Translated directly, “blan mange” means white food, but in Haiti, “blan” also means “foreigner,” so really, blan mange could translate into “foreigner food.” My brother and sister and I would scoop up every spoonful of the jiggly white dessert. It was as sweet and scented with coconut as a day on a Haitian beach.

We spent several summers in Haiti after that first visit. I soon became accustomed to this hot, dusty land. I learned to speak rudimentary Creole and became acquainted with most of my extended family.

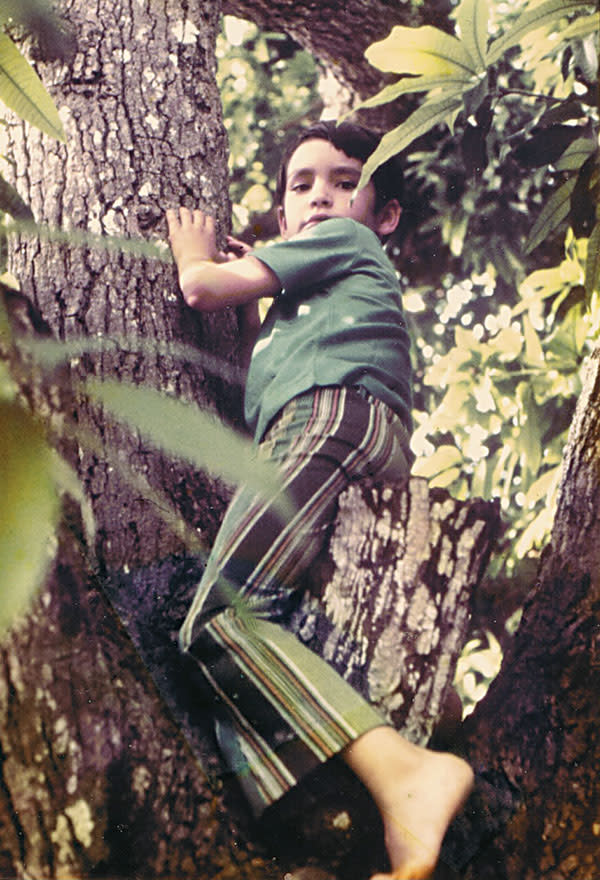

Children were left to roam, adventure and discover. We climbed the towering trees in my grandfather’s yard hunting for ripe mangoes. We peeled the fruit with our teeth and chomped on the meat like it was life itself, the sweet, sticky liquid dripping down our chins, necks and chests. Barefoot, half-naked and completely filthy, we were like animals—free, wild and part of the parched landscape.

In the summer of 1975, when I was 11, my brother and one of my cousins and I took the midnight walk in the pitch dark from my grandfather’s house to my aunt’s chicken processing plant so we could witness the slaughter. Workers hung fowl upside down on a conveyor and sliced their heads off. After the birds bled out, they were gutted, de-feathered and packed in ice for delivery to markets before daybreak. Sometime around 4 a.m., my cousin, Jean-Michelle, who managed the plant, offered me a bottle of Barbancourt rum and smiled at me. “It’s coffee,” he said.

I took a sip, expecting rum, but what I got was indeed coffee. It was cold and strong and sweet like syrup, and to this day I believe it was the best drink of coffee I ever tasted. Haiti’s rich and turbulent history is vehemently linked to those two wicked crops, rum and coffee. Sweet coffee: the blood of a tragic and proud nation.

The main road, along which most of my relatives lived, was still unpaved, rutted and dusty. The mashan—market women—passed, carrying baskets on their heads or leading donkeys loaded with fruits, vegetables, goats, chicken or charcoal. To this day Haiti does not have industrial farms. Agriculture is a communal affair. Groups of peasants form what is called a kombit to clear land or harvest crops in small family plots, a tradition that goes back to Africa and which is also a result of the country’s painful colonial past.

In the 18th century, when Haiti was a French colony—in fact, the richest colony in the world—and was still called Saint Domingue, it had 655 sugar plantations, producing an average of about 131 million pounds of sugar a year. After the Haitians revolted and won their independence in 1804, the large plantation system collapsed. Most of the country’s people were former slaves who had suffered deeply under the colonial rule. They wanted freedom. They abandoned the plantations for the mountains and built straw and mud huts and cultivated their land for their own food—a system of subsistence agriculture that remains prevalent to this day.

During those summer vacations, we walked everywhere. If we got hungry, we bought snacks from the mashan on the side of the road—pate, pastry squares about the size of a small hamburger with flaky outer crust and a dollop of spicy ground beef inside; or bisuit bread; or small cones of raw sugar that were tightly wrapped in paper. We bought single cigarettes and hid in the yard and smoked. We spent our days hunting lizards with nooses we fashioned from palm fronds, chased chickens, picked guava and kenep trees clean of fruit and snacked on almonds that fell from the huge tree in my aunt’s patio.

My cousin, Caroline, and I borrowed Jean-Michelle’s horses and raced through the flat plain where sugarcane grew in rows that seemed to disappear into the horizon that stretched towards the ocean. Peasants used their machetes to chop stalks of cane for us. We rested under the ruins of a sugar-processing mill that dated back to colonial days and peeled the cane with our teeth, chewed the stalks, and drank the sweet juice that jolted us with a burst of energy.

At the height of summer, when the heat grew intense, we would go up to my grandfather’s cabin in the mountains of Furcy, about an hour’s drive from Port-au-Prince. Furcy is always cool, and the land is rich and fertile. The scenery of pine trees and red clay roads and meandering peasants has changed little in 50 years.

A dozen of us kids stayed in the cabin. At night we played cards under the dim light of a propane lamp and slept on saggy bunk beds. In the mornings it was misty and cool. We rode horses to the market in Kenscoff and walked to a natural pool with a waterfall and dipped in the freezing water. But the best part of spending time in Furcy was roaming the countryside with the peasant kids, picking peaches and apples from trees, munching on wild berries, and biting into raw corn and cabbage. Food grew everywhere.

Back then, Haiti cloaked us in the illusion of paradise. In 1975, the country was ruled by then 24-year-old dictator Jean Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier. As children we were not aware of his family’s dark history. We were not aware that somewhere near the ocean past downtown Port-au-Prince, there was an ugly yellow building called Fort Dimanche where thousands of Haitians had been jailed and killed. Nor did we realize that just about every adult knew someone who had disappeared or had been killed by the Duvalier regime. We had no idea that every Haitian lived in daily fear of knowing he or she might be next, simply by saying the wrong thing to the wrong person, angering a Tonton Macoute—a member of the Duvaliers’ ruthless paramilitary force—or by just being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I didn’t return to Haiti until 1991. It no longer seemed like the innocent paradise of my childhood. I had changed, or maybe it had. And it continued to change on every one of my visits after that. There seemed to be a new president or military junta every year. The U.S. military invaded and occupied the country. United Nations helicopters flew overhead. A road was built where the sugarcane fields once were. There were more people. My grandmother died. And with her went the recipe for her blan mange.

I admit I mourned the loss of that coconut dessert as much as Mamish’s passing. What else did I have to tie me to her? I never really knew her. But I had eaten her blan mange with relish and I still savored it in my memory.

I never stopped searching for a blan mange like hers. I tried it at a number of restaurants in Port-au-Prince and Petion-Ville, at my cousin’s house—but none of them came close to my grandmother’s perfect dessert. I began to wonder if time and nostalgia were clouding my memory of that divine white coconut custard-like gelatin. Perhaps, I thought, it was just me making a big deal out of nothing. It had been almost 20 years since my grandmother died. How could I remember the flavor of a dessert I had tasted only a few times in my childhood?

But a few years ago, some time after my grandfather died, my mother called from Miami and said that while going through some of his possessions, she had come across Mamish’s recipe. According to the notes scrawled in cursive with pencil on a fraying piece of yellow paper, the cook had to remove the meat of the coconut with a knife, then remove the brown skin and grate the meat. Then she put the grated coconut into a sieve, poured milk over it and squeezed and pressed out all the liquid. My grandmother then used cheesecloth for a second sieve to make her own coconut milk.

After hearing the instructions, I lost all hope. Who today would have the time and energy to make this dessert?

Then, last year, our family gathered at my mother’s house in Miami for the holidays. After a delicious Christmas Eve dinner, my mother brought out the desserts and placed them on the table. There, between the flan and the chocolate mousse and the Key lime pie, was a rectangular Pyrex dish holding an opaque white gelatin with toasted coconut shavings on top.

Before I served myself, I asked my mother how she had managed to make it. She explained she had come across an exile’s version of the recipe that was floating around Miami. She experimented for months, trying different things, using various brands of canned coconut milk and packaged coconut.

She watched me as I took my first bite. The silky texture between my palate and tongue gave way to the intense coconut taste of my youth. I was back in Haiti. My grandmother was there, smiling, watching me dig into her blan mange. It was beautifully balanced: sweet like raw sugar cane on a sweltering day, soft like a tropical breeze teasing green palm fronds, and as simple and rich as the heedless summer days I spent in paradise.

Mamish’s Blan Mange

I didn’t really get to know my grandmother on our long-ago summer visits, but she lives on in my memories of her coconut dessert.

One 13.5-ounce can coconut milk

One 14-ounce can condensed sweet milk

1 cup milk

1 cup evaporated milk

¼ cup cold water

2 packets unflavored gelatin

1 teaspoon vanilla extract (optional)

Toasted grated coconut (optional)

Place the cup of milk and the condensed milk in a pot and heat to the boiling point but do not boil. Then turn heat off.

In a bowl or Pyrex dish, mix the coconut milk and evaporated milk.

In a separate container add the 2 packets of gelatin little by little into the ¼ cup of cold water and mix until fully dissolved.

Add two tablespoons of the warm milk to the gelatin and continue stirring. Add another two tablespoons of the warm milk to the gelatin and continue stirring until gelatin is dissolved. Then pour the gelatin mixture into the warm milk while stirring. If you have clumps in the gelatin, strain.

Once the gelatin is in the warm milk mixture and there are no clumps, pour this mixture into the bowl with the coconut milk and evaporated milk, add the teaspoon of vanilla if desired and stir well.

Let it cool and then place in refrigerator for at least 6 hours.

Sprinkle toasted coconut shavings on top before serving.

Sarasota’s Phillippe Diederich is a writer and photojournalist. He was awarded the Chris O’Malley Prize for Fiction from The Madison Review and has received an Elizabeth George Foundation Grant, a Florida Individual Artist Fellowship in Literature and a John Ringling Towers Grant in Literature. His first novel, Sofrito, will be published in April by Cinco Puntos Press.