The Ringling's Rupp Pavilion Heads Toward a Restoration

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Visitors to the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art recently may have noticed the metal fencing and signage around a small, circular building across from the entrance to the Circus Museum. That’s because work is set to begin in October on the restoration of the building, known as the Rupp Pavilion—a midcentury modern design by the Sarasota School of Architecture’s William “Bill” Rupp.

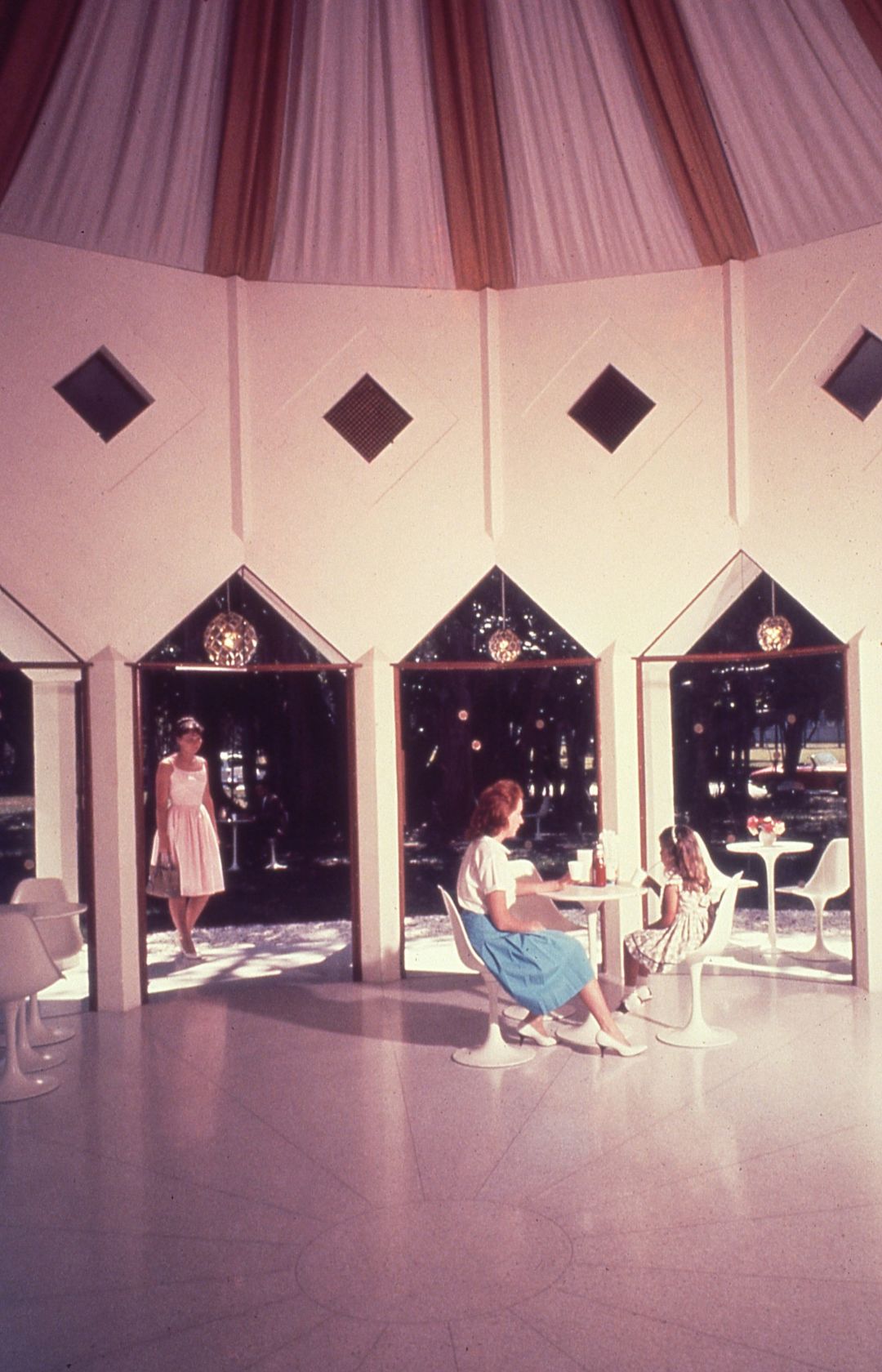

The pavilion was for many years known as the Banyan Café, a spot where museum-goers could stop off for a quick bite to eat—a burger, hot dog or other type of sandwich and a beverage to keep them going on their explorations of the museum and its grounds. (It’s been closed for several years now.) But the building started off as an eatery operated by (who’d have guessed it?) the Howard Johnson restaurant chain. Commissioned by the Ringling’s second director, J. Kenneth Donahue, it was built to Rupp’s design by Ringling maintenance workers for the even-then modest sum of $15,000, becoming the first food concession stand at the Ringling when it opened in 1961.

Image: Staff Photo

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

The restoration of the Rupp is something of a personal mission for current Ringling director Steven High. On a recent tour of the building, High pointed to its interior columns, its original diamond-shaped windows below its domed ceiling and oculus, its still-intact terrazzo floors and even the scuppers that Rupp designed to direct rainwater outside.

“I see it as a sculpture,” High says of the approximately 900-square-foot building. “And we want people to be able to come inside and explore it.” Once restored—a project estimated to take about six months—the pavilion may be used to host programs on midcentury modernism, perhaps some student programming, and could even be available for rentals and intimate cocktail events as well.

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

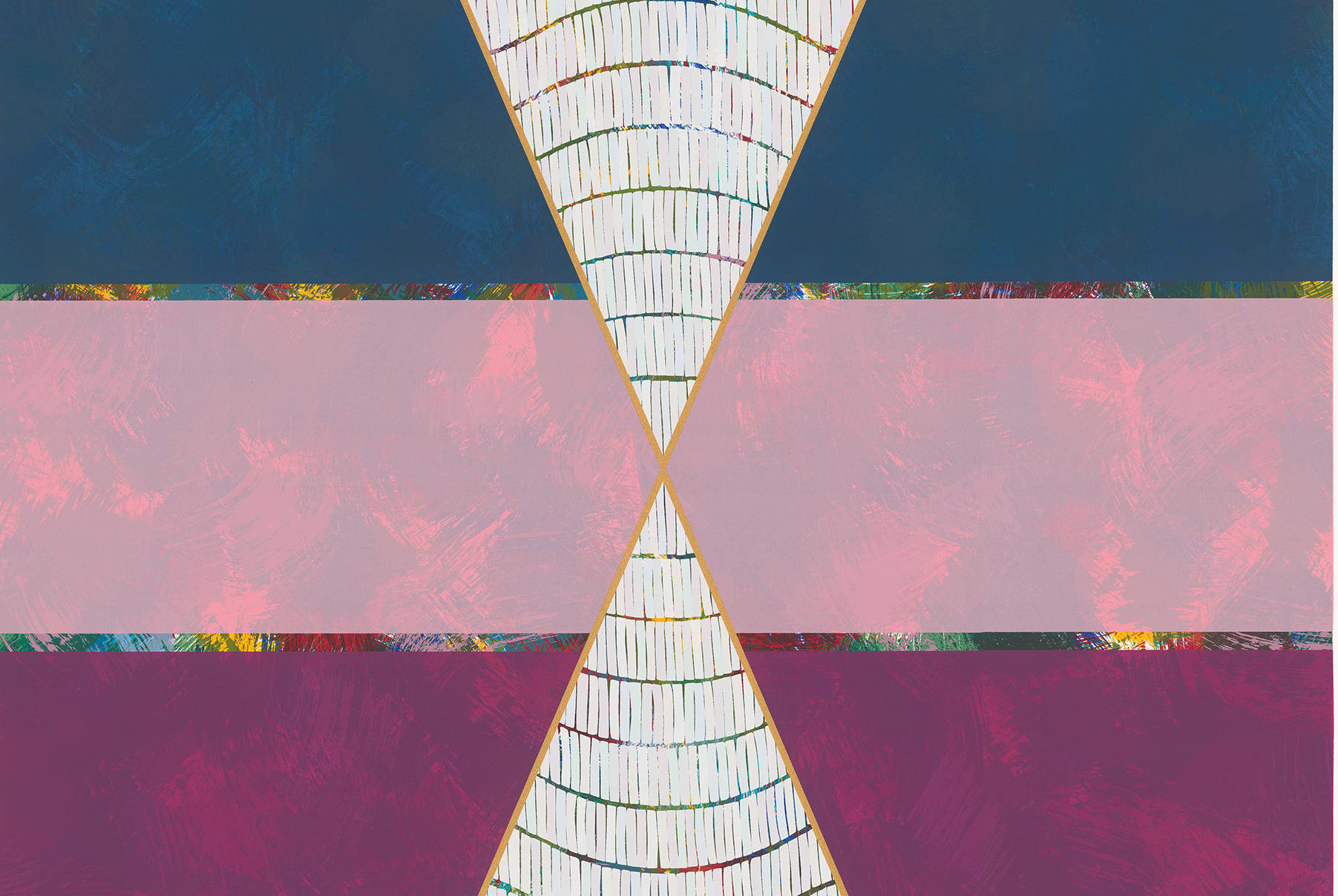

The restoration will keep as much of Rupp’s original plans as possible, including the central “timepiece” skylight that marks the passage of the sun across the course of a day, while adding hurricane glass, ensuring wheelchair access and making room for up-to-date HVAC systems and storage. Willis Smith Construction will handle the work under the supervision of architect Linda Stevenson, who has an extensive background in historic preservation.

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

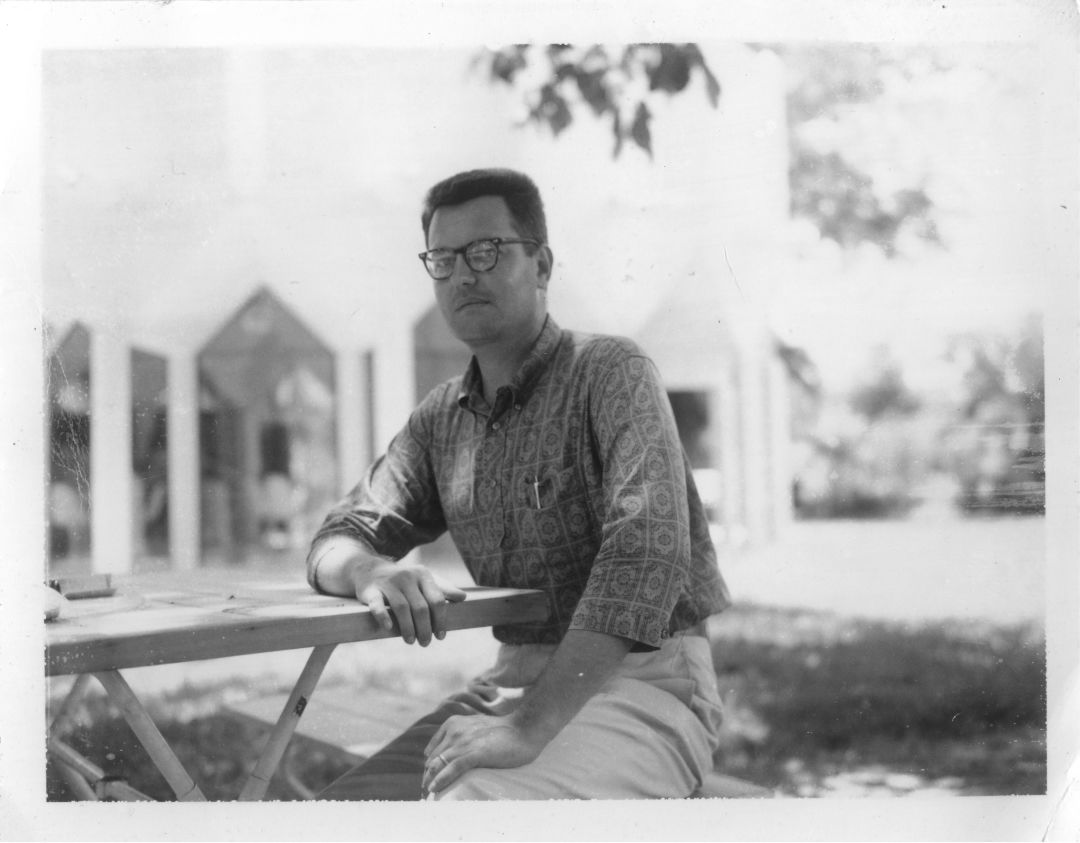

For those who aren’t familiar with Rupp and his reputation, he was one of the youngest of the architects who came together briefly in 1950s and 1960s Sarasota to work employing modern principles of design and innovative construction methods while creating a practical but creative response to the Florida climate. Among his peers were the first of the group, Ralph Twitchell, along with Paul Rudolph, Jack West, Gene Leedy, Tim Seibert, Victor Lundy and Bert Brosmith.

Rupp partnered for just a couple of years starting in 1959 with fellow architect Joe Farrell; among their projects were the Barkus Furniture Company showroom on South Orange Avenue that now is called the McCulloch Pavilion and is on the National Register of Historic Places (home to Architecture Sarasota); the Manasota Key Beach Pavilion; residences on 42nd Street and in Lido Shores; and (with Leedy) Brentwood Elementary School.

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Rupp was also featured in Architectural Forum’s 1961 issue dedicated to “New Talent for the Sixties” and in Life Magazine’s “The Takeover Generation” in 1962, along with such fellow up-and-comers as writer John Updike, singer Leontyne Price and playwright Edward Albee. He departed for Naples, Florida, in 1965 and then eventually moved to New York City and Amherst, Massachusetts, where he continued to design. He died in 2002.

In that Architectural Forum article, the writer said as a compliment to the pavilion, “It looks not at all like a hot-dog stand.” The restoration project should serve to confirm that response once again.