From New Urbanism to Suburbanism, Venice Is a Tale of Two Cities

Editor’s Note: An original version of this story was published in the April 2015 issue of our publication Venice Magazine.

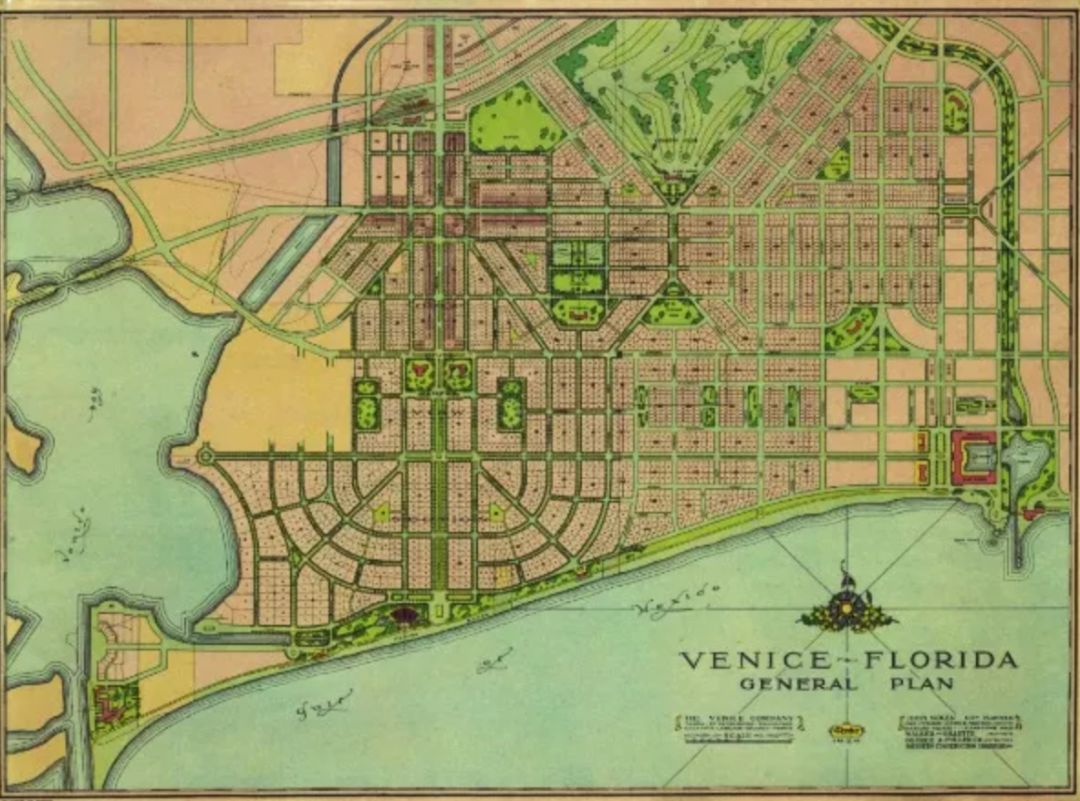

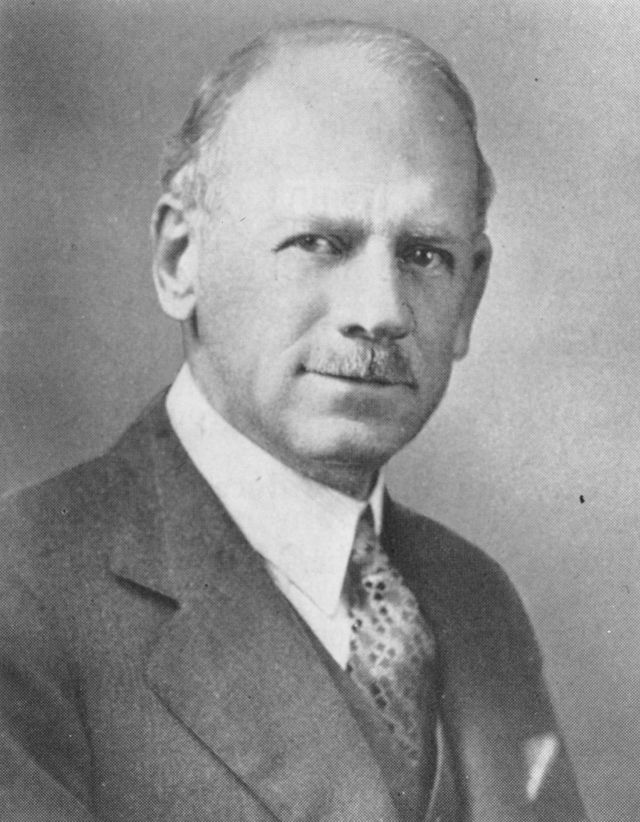

John Nolan is the visionary planner who brought European-style, walkable communities to the United States in the early 20th century. Nolen enjoyed considerable fame during his life, and his work has been featured in a PBS documentary and inspired such master-planned communities as Seaside in the Florida Panhandle and Disney’s Celebration near Orlando. City planners and academics regularly make pilgrimages to Venice, which Nolen designed in the mid-1920s, to experience what they call an example of one of the best-planned cities in the United States.

The city’s fidelity to Nolen’s 1926 plan, through real estate booms and busts over the decades, while other communities built suburbs, garnered it recognition from the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 2010, one of only three cities to have their plans so designated. Before the real estate collapse of 2008, city leaders and developers seemed to embrace Nolen’s vision for the city, proposing new developments that adhered to his principle of walkable neighborhoods for diverse income levels clustered around a central downtown.

But as Venice is expanding northeast, with thousands of housing units in communities on and near what used to be the Henry Ranch, Nolen’s plan has been left behind in favor of suburban-style gated communities.

The blueprint that’s still working almost a century later.

Image: Courtesy Photo

The Road to Suburbanism

All you have to do is spend some time on Venice Island and compare it to places outside the city to understand why the Nolen plan has won so many accolades. Unlike many Southwest Florida communities, Venice has a real downtown, with restaurants and shops close together so you can spend hours entertaining yourself without having to get into a car or inhale recirculated mall air.

You can rent an apartment above downtown stores or in the nearby apartment district, or you can buy a million-dollar beach home or something in between. And in any of those living environments, you won’t stroll too far from your front door without encountering a park. You can walk to central Centennial Park and play tennis or basketball, enjoy music at the gazebo or attend art shows and the annual lighting of the Christmas tree. You can walk or bike nearly everywhere you’d want to go in town—to the library, Venice High School, or a handful of beaches and the scenic jetties, where the Intracoastal Waterway and the Gulf merge.

While Venice has stayed true to its plan, for most of the last century, downtowns all across the country withered and suburbs proliferated. But Nolen’s ideas enjoyed a revival, starting in the 1990s, with architects and planners who called the idea of walkable communities with plenty of green space organized around a central municipal area “New Urbanism.” Many in Venice continue to take pride in the city’s layout and character; the city even has a campaign around Nolen’s story and vision to increase tourism.

“We have the largest collection of historic buildings and homes in Southwest Florida,” says James Hagler, the director of the Venice Museum and Archives. “Visitors can come see, walk and look at the Nolen plan. We are totally a walkable community.”

A little more than 15 years ago, many civic leaders and developers believed that the city’s future should look like its past. After dozens of community meetings with hundreds of residents, city leaders presented a plan called Envision Venice, which encouraged developers to build Nolen-like communities. And for the hundreds of acres of undeveloped ranchland east of I-75, where the suburban communities of Willow Chase and Venetian Golf and River Club went up, city leaders called for villages, “compact, pedestrian-oriented, mixed-use development.”

The city planned to allow slightly more density for developers who included “affordable, workforce housing” and “units for lower income workers and seniors.”

The building industry responded. Developer Mike Miller proposed a Nolen-style project on 73 acres near Knights Trail Road, and city leaders and planners lauded his idea. The project featured single-family homes, apartments and workforce housing and a downtown Main Street in the interior with a movie theater, a hotel and shops, interconnected streets and a number of parks and greenways.

Across the street, on the south side of Laurel Road, the Gulf Coast Community Foundation (then named the Gulf Coast Community Foundation of Venice) planned the Bridges. Former foundation president and CEO Teri Hansen hailed the project as “a mixed-use of mixed-income community homes for working families.”

The Bridges’ marketing materials promised a new urban model for the rest of the country to duplicate, with about 200,000 square feet of commercial space in a traditional downtown. The foundation had plans for Harvard researchers to come here and study the social aspects of the development. The foundation also acquired an adjoining 150 acres for future development, spending about $30 million on land and development costs.

Then, just as in Nolen’s time, a recession hit, and both projects died.

But as the economy rebounded and real estate took off again, developers said that as attractive as the island of Venice may be, that’s not the kind of design that would suit their target buyers. Instead, they began building the type of housing that active adults and relocating families want to see.

“The suburban model is what people want,” says John Peshkin of Vanguard Land, whose company has developed two communities with about 2,400 homes east of I-75 near Laurel Road. “That’s why we are all suburban builders out here.”

Grand Palm

Image: Courtesy Photo

Pat Neal, the most prolific builder in South County, credited with building communities including Grand Palm, Vicenza and Cielo, agrees.

“In Nolen’s time, the automobile had not begun to dominate American residential planning,” Neal says. “Everything had to be walkable. Now, overwhelmingly, the market prefers 21st-century building.” Neal says Nolen-style communities represent only 5 percent of what he’s building today. “New Urbanism is cute and builds community and has its place,” he says. “And we’d build more of it if we saw a market for it.”

Southwest Florida newcomers are snapping up new homes in suburban-style communities, but Ed McMahon, a senior resident fellow at the Urban Land Institute, a nonprofit that studies and promotes sustainable communities, says that doesn’t mean New Urbanism principles no longer have appeal. Many established Florida downtowns with a mix of housing and commercial establishments, from Seaside to St. Petersburg to Venice Island itself, are attracting residents of all ages, including wealthy retirees, and McMahon says homes in such walkable downtowns have enjoyed larger relative price increases than most gated communities. “Walkable communities create value,” he says. “The market is changing as demographics are changing. People want to have more choices in housing.”

John Nolen

Image: Courtesy Photo

The Man Behind the Plan

When Nolen began his career in the early 1900s, city planning in the United States was going through a transformation. The Industrial Revolution had pushed more people into cities that developed haphazardly, without much thought about sanitation, health and how communities could best function. Doctors had only recently discovered that germs caused disease, causing a new concern about clean water, sewage control and sanitary living conditions. Nolen, who has been called the dean of modern urban planning, adopted and popularized the new ideas of how to design healthier, more livable communities, and he designed more than 50 town and city plans across the United States.

Born in 1869 in Philadelphia, Nolen was orphaned at an early age. He grew up and was educated at Girard College, a boarding school for orphaned and disadvantaged children. Tenacious and bright, Nolen earned a spot at the prestigious Wharton School of Finance and Economics and majored in economics and public administration. He then spent 10 years as executive secretary of an organization that provided college night classes to the urban working class. Because of his humble beginnings, Nolen had a strong sense of social justice, which infused his work.

Nolen’s trip to England in 1895, where he took a summer course at Oxford, changed the trajectory of his career and the face of many communities across the country, including Venice. While there, he became enamored of the so-called “Garden Cities” springing up in the English countryside. These were medium-sized new towns surrounded by greenbelts. Professional designers planned the new towns to be self-sustaining with farms, commercial and industrial areas as well as residences for workers and people from all walks of life.

Nolen brought the concept back with him when he returned. The United States did not have schools of urban planning at the time, so Nolen enrolled in Harvard’s School of Landscape Architecture. He then set up an office in Cambridge, where he practiced both landscape architecture and urban planning. He also became president of the newly formed National Conference on City Planning and a spokesman for comprehensive planning, greenbelts and zoning requirements.

In the 1920s, Nolen headed to Florida, where a real estate boom, made possible by the expanding reach of the railroads, was under way. Chicago socialite Bertha Palmer had put the Sarasota area on the map, purchasing thousands of acres of land and building a winter home here. Her presence attracted prominent Northerners, including Fred Albee, a pioneering inventor and doctor who created some of the first orthopedic surgery devices during World War I and performed the first bone graft.

Albee purchased multiple parcels from Palmer, including 1,426 acres of what is now Venice. In one of the most lucrative land flips of the time, Albee paid $185,000 for the land, holding it for just nine weeks before selling it to the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers for $1 million. The BLE, then one of the country’s largest labor unions, was trying to recoup investment losses by jumping into the hot Florida real estate market.

The BLE gave Nolen a blank canvas along the Gulf of Mexico to plan his ideal city and then allowed him to build it. Nolen got involved in hiring the other professionals, including well-known landscape architect Prentiss French. The BLE built three hotels, the downtown business district and hundreds of buildings before the real estate market crashed. The BLE lost its holdings, with some of the property reverting back to Albee.

Nolen and an associate working on the Venice plan.

Image: Courtesy Photo

When construction resumed around the nation after World War II, the expanding U.S. highway system and a rising stream of cars carried people to new suburbs, where stores were located along central streets and homes were built in strictly residential areas.

But Venice pulled out Nolen’s plan and mostly stuck to it. The plan covered what is now the island and the Edgewood neighborhood, the area Nolen designed for workers, east of U.S. 41 Bypass.

“The east parts of the city were farms and ranchland to provide food for the community,” says Bruce Stephenson, a professor of environmental studies at Rollins College and author of the book, John Nolen, Urban Planner and Landscape Architect. “The logic in the 1920s is that you had to grow your own food,” he adds. “Protecting agricultural land and water supplies was important.”

As Florida experienced decades of rampant growth and periods of drought after the war, leaders and the public grew concerned about water supplies and the cost of infrastructure to support the expanding population. In the late 1980s, the state enacted the Growth Management Act to give the state power to regulate big developments. In the 1990s, there was a resurgence of interest in Nolen’s ideas—now called New Urbanism—and many cities across the country started reinvesting in their downtowns.

Miami planner Andres Duany became one of New Urbanism’s best-known proponents, and he started planning Nolen-like communities across the country. He often pointed to Venice as an example of how to build a pedestrian-friendly city.

Venice grew rapidly in the early 2000s through a series of controversial annexations, including the 1,000-plus-acre Henry Ranch, east of I-75. Developers started building the Venetian Golf and River Club and Willow Chase, both suburban developments, before the city gave much thought to how the area should develop.

In 2005, prompted by state regulations requiring a comprehensive plan, city leaders, with the participation of hundreds of residents, started working on a 25-year plan called Envision Venice, which included the remainder of the Henry Ranch property. On the island, the plan encouraged multistory buildings and density. A number of residents, mostly retirees, became alarmed, and they organized. They saw the new plan as threatening Venice’s small-town charm.

In 2007, just as the Envision Venice document was on its way to the state, voters kicked three incumbents out of office and replaced them with three who wanted slower growth. Then they went line by line through the Envision Venice document, putting a hold on projects pending before the city and reducing building heights.

By then, the real estate market was quivering. The first New Urbanism casualty was the Miller project on east Laurel Road; after it stalled, Miller lost the property through foreclosure. The Gulf Coast Community Foundation shelved its Bridges project (but is still holding the land “for investment purposes,” according to a spokesman). Soon, the real estate market had completely collapsed and the city went two years without issuing a major building permit.

After pro-business Rick Scott was elected governor in 2010, the Legislature repealed the Growth Management Act, so now it is mostly up to local government to make planning decisions. Sarasota County had a change in the composition of its commission, with the new commission friendlier to developers and less insistent about environmental protection, and the commissioners started to relax growth restrictions east of I-75.

There were political changes in Venice, too. In 2011, voters replaced all three slow-growth council members elected a few years earlier in favor of a business-friendlier board.

In 2011, John Peshkin’s Vanguard Land purchased the Miller land and came before the city with a plan for 1,700 suburban-style homes, called Toscana Isles. Peshkin’s proposal was the first major building project in years, and revenue-strapped officials were happy to have it. No one was thinking about walkable Nolen communities, and no plan was in place mandating the New Urbanism principles.

“The lots have been sitting there a long time,” said then Mayor John Holic. “No one ever got around to saying how that area should develop.”

After the city and county extended Jacaranda to Laurel Road, providing a vital link, multiple proposals for east Laurel Road hit City Hall in quick succession: Portofino (650 homes); Villages of Milano (700 homes); and the Woods at Venice (263 homes).

The developments have clubhouses, pools and modern amenities and are similar to other gated communities throughout Florida.

Adam Hancock, a Southwest Florida real estate agent and owner of the Adam Hancock Group, sees some of the best homeowner value in the area. In Venice, the real estate market is more affordable than within the City of Sarasota, but still boasts reasonable proximity to beaches, desirable schools and design that make family living easy.

“There are lots of kid-centric amenities like playgrounds, children’s pools plus proximity to nature, beaches and trails. It's not just a retirement scene, it’s changing,” he says.

On the island, though, Nolen’s plan remains gospel. The city has added more and wider bike paths, including the Legacy Trail. It has added more parks, including the waterfront Maxine Barritt Park and several pocket parks. The city has tightened building standards in the historic districts, requiring Northern Italian Renaissance design and a palette of acceptable building colors.

Pre-pandemic, the downtown was thriving with new shops and restaurants. In 2019, a Beautification Project of Downtown Venice was completed, reconstructing 14 blocks, the Venice Fishing Pier was refurbished and Julia Cousins Laning and Dale Laning Archives & Research Center opened at 224 Milan Avenue—just steps away from the relocated Triangle Inn, which now serves as the Venice Museum and Archives. In 2020, a new Public Safety Facility (home of Venice Police Department) opened.

The Venice Museum expanded to include permanent exhibits about the city’s history, including the circus, the Kentucky Military Institute and, of course, Nolen.

It’s ironic, perhaps even poignant, that just as Nolen’s plan is being fully realized on Venice Island, it seems to have lost its relevance as a blueprint for the city’s future growth. Instead, it’s becoming something of a museum piece, a charming urban design that people enjoy and drive to visit; then they return to their gated, all-residential neighborhoods a few miles east.

“We are just trying to attach to the city,” says Neal about his new communities. “Downtown is an amenity; it’s gorgeous. It’s just not in the style in which our buyers prefer to live.”

“There are two Venices,” says Don O’Connell, former president of the Venice Area Historical Society and owner of 30 apartments in the historic district. “We’ve got the island and then everything else.”