'There Aren't Enough Tests': A Sarasota Native Shares Her Experience With COVID-19

Kirstin Whitmire rests after showing symptoms of coronavirus: fatigue, fever, cough and shortness of breath.

Image: Courtesy Kirstin Whitmire

Kirstin Whitmire, 28, a Sarasota native who now works at a hospital in Alabama as a medical lab scientist, returned to Sarasota with her mother after an international trip earlier this month. On her flight home, she developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19. This is her story.

“I’m from Sarasota, and my parents still live here. Today I work at a hospital in Alabama as a medical lab scientist; I have an M.S. in clinical laboratory science and am a certified [American Society for Clinical Pathology] clinical laboratory scientist. I also spent three years studying virology.

“On Feb. 25, I flew out of Tampa International Airport to go to Egypt with my mother. We flew in and out of Frankfurt, Germany, on our way to go on a Nile cruise, then returned to the U.S. on March 13.

“The morning of our flight home, I woke up at 1 a.m. and wasn’t feeling well. I was really tired—even my mom noticed. It had been a long trip, and I hadn’t really slept a lot, so I thought it was just stress and exhaustion. I was ready to get home.

“Halfway through our 12-and-a-half-hour flight, I started to feel feverish, with a sore throat. ‘You’re really flushed,’ my mom told me.

“I didn’t have shortness of breath and wasn’t coughing, but I definitely wasn’t feeling well. There were also other people who were noticeably ill on the plane. One person was actually coughing up mucus, and I wondered how they were going to be let into the country [due to the travel restrictions being put in place]. But when we got back to the U.S., customs officials asked us where we’d traveled to, and then said, ‘Welcome to the United States.’ I didn’t even have to answer the usual questions about bringing livestock or food into the country or fill out the customs declaration card.

“Late that same night, after we’d gotten home, I started coughing. My mom got worried and ran out to the store to get a thermometer and confirmed that I did have a fever. I also felt like I couldn’t catch my breath, and my chest was tight—like I couldn’t untangle a knot that was inside. I’ve had the flu and pneumonia, and the shortness of breath reminded me of pneumonia, but the tightness was so strange—I almost wondered if I was having a heart attack. It was so painful to take in a breath; like there was glass in my chest. At that point, I began to wonder if I had COVID-19, although I was hoping I had the flu.

“I don’t live in Sarasota anymore, so my primary care physician isn’t local. Because my mother and I had been to areas that had confirmed cases of the virus, we called the Centers for Disease Control's hotline and then called the Florida Department of Health’s. I was told that with my travel history and symptoms, especially my shortness of breath, I should definitely go to the emergency room to get tested. We called [a local] hospital’s emergency room to let them know I was coming, and they agreed that I should.

“At the first hospital, I was put in triage for two hours and not seen by anyone. I wasn’t isolated, and the hospital said I didn’t qualify for the COVID-19 test, even with my symptoms. It didn’t feel like protocols were being followed, and I was uncomfortable staying, so my mom and I left.

“By that time, my fever was spiking, and I felt like I couldn’t breathe, so we went to a second hospital. When we arrived, the staff immediately put me in isolation, and before I even touched the bed, they swabbed me for strep and the flu. A doctor came into the room asking about where I’d traveled and, because I was having trouble breathing, she ordered a chest X-ray.

“My tests for strep and the flu came back negative, and the chest X-ray didn’t show any severe symptoms. I’m 28, young and healthy. The doctor told me I wasn’t high-risk for severe symptoms, but that they thought I should be officially tested for COVID-19.

“However, the doctor said they didn’t have tests available at the hospital, so they would have to send my sample to the state health department—and that because of my age, and the fact that I didn’t have severe enough symptoms or other health issues, the health department would reject my sample. They told me it would be a waste to try and send it off, even though the doctor was sure I had the infection.

“Because of my job, I have a unique perspective on the science of testing, so I was shocked to find out that the hospitals here didn’t have COVID-19 tests on hand.

“I was ultimately diagnosed with COVID-19 and sent home with a packet of information about how to treat it and how to self-isolate. My mom—who has had respiratory issues ever since 2018’s red tide outbreak and uses an inhaler—was told to isolate herself from me, as well. She’s now working from home and unable to see my grandparents or my aunt, who’s suffering from breast cancer, in the event that she caught it from me.

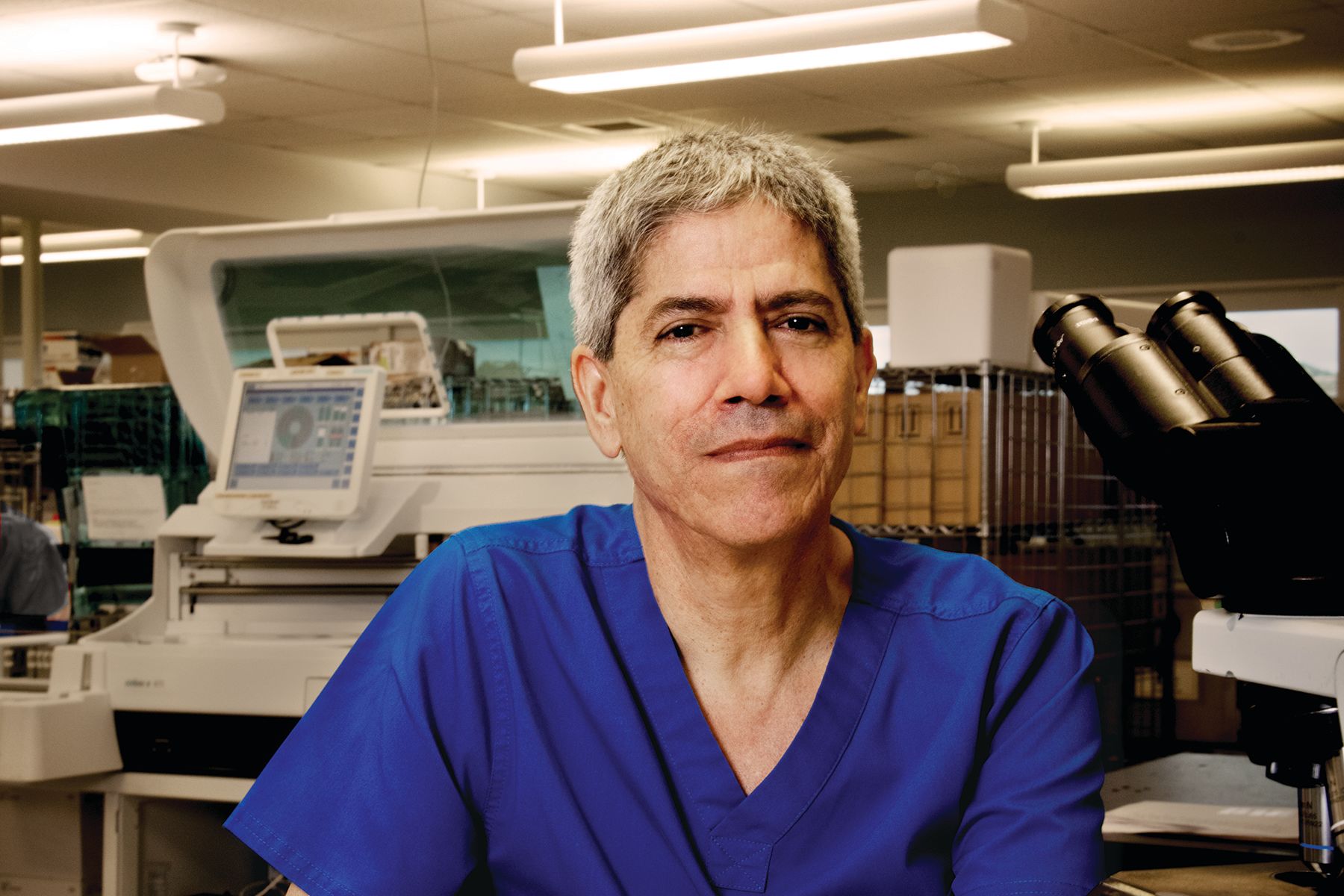

Whitmire at the hospital

Image: Courtesy Kirstin Whitmire

“I did one week of isolation in my childhood room in Sarasota and I have one more week before I can go back to work. I’m feeling a lot better; Friday [March 20] was the first time in eight days I woke up without a fever, and I’m hoping it stays that way. I do have a lingering cough, and was told that’s what sticks with you, and will likely hang on longer than the virus itself. My mom [was tested] on Monday and we’ll finally know whether she has COVID-19 or not.

“I’m not an expert on global pandemics or an epidemiologist, but I do think our health care system dropped the ball on this crisis. I’m a naturally optimistic person, and I don’t think that because something isn’t perfect, it can’t get better. I do think that hospital administrators and, hopefully, the government will take this experience and learn from it. Already, it’s been a few weeks since I couldn’t get tested, and more testing capabilities are opening up. Lab workers are putting on their gloves and churning out results, and countries are sharing data and testing. I think in the future we’ll all be more prepared.”