Local Salsa Fans Keep the Genre Alive by Connecting With Its Rich History

Izzy Sanábria

Image: Joe Lipstein

After almost 60 years as a Chicagoan, Juan Montenegro, 73, moved to Sarasota with his wife Claire in 2017. Energetically fit and full of el fuego, on one typically sun-soaked Sarasota day, Montenegro set out to get to know his new neighborhood. As he arrived in the Rosemary District, he came upon the studios of the community radio station WSLR. Montenegro walked in, introduced himself and the station picked up a show he had retired decades before.

“Latin Explosion originally aired in Chicago during the ’70 and ’80s,” Montenegro says. For his current show, he brings in el sazón every Friday morning.

Montenegro identifies as Hispanic and Latino, and yet underscores that the term “‘Hispanic’ is a government word and not a word from the community.” His voice is boisterous and buoyant as he spins salsa, Latin jazz and Afro-Cuban music, showcasing a wide range of artists.

The show features labels like Fania Records—essential to the New York salsa movement of the ’60s and ’70s—yet delivers more than music. Interviews with key players in the Latin music scene give the program gravitas. On his show, Montenegro has featured Fania co-founder Johnny Pacheco (who died in 2021) and, most fascinatingly, Izzy Sanábria, whose album cover designs formalized an aesthetic that reached well beyond the dance floor and have dotted Boomer record collections for half a century. Sanábria is now 83 and lives outside of Tampa. He identifies as Nuyorican, originally a pejorative term for New York Puerto Rican.

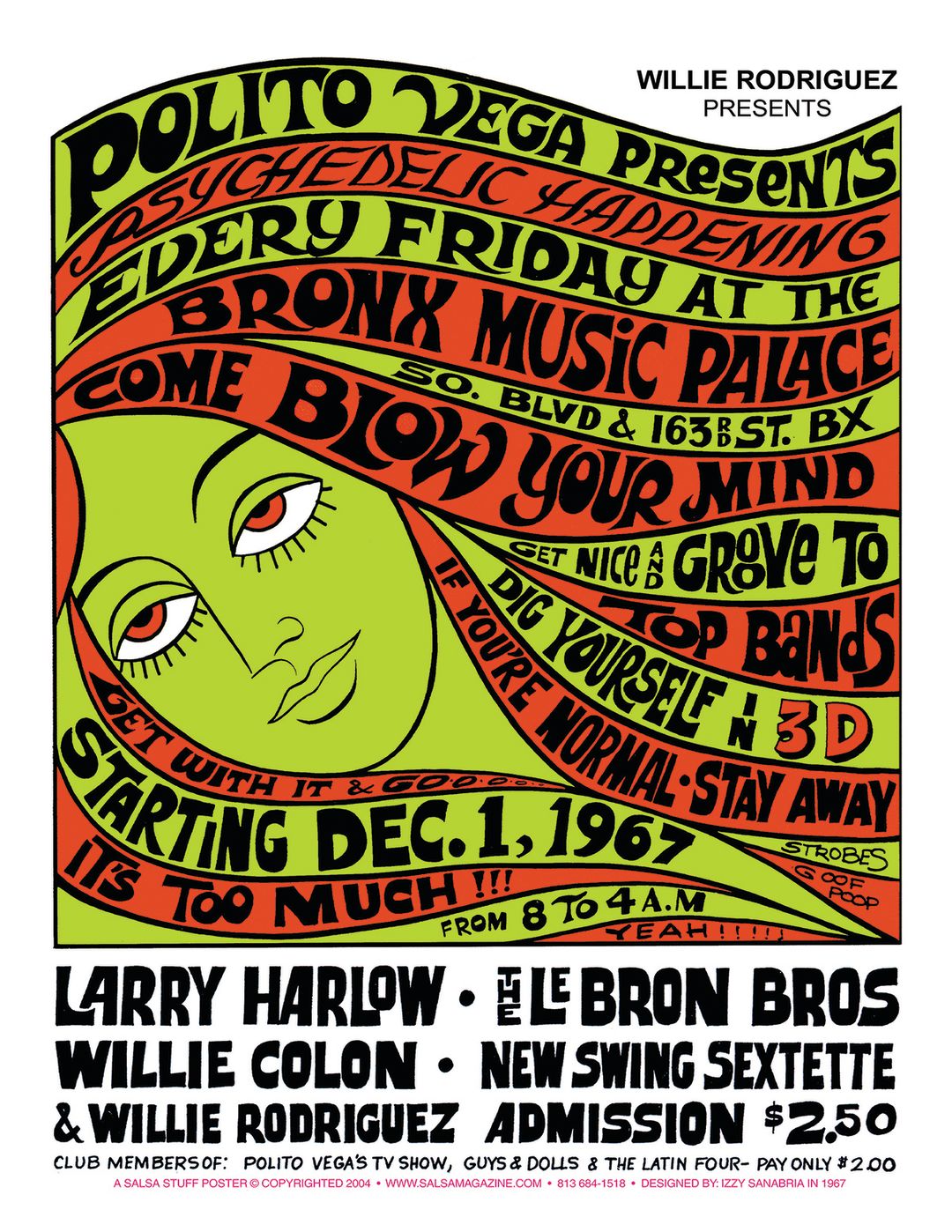

A 1967 concert poster designed by Sanábria

Image: Courtesy Photo

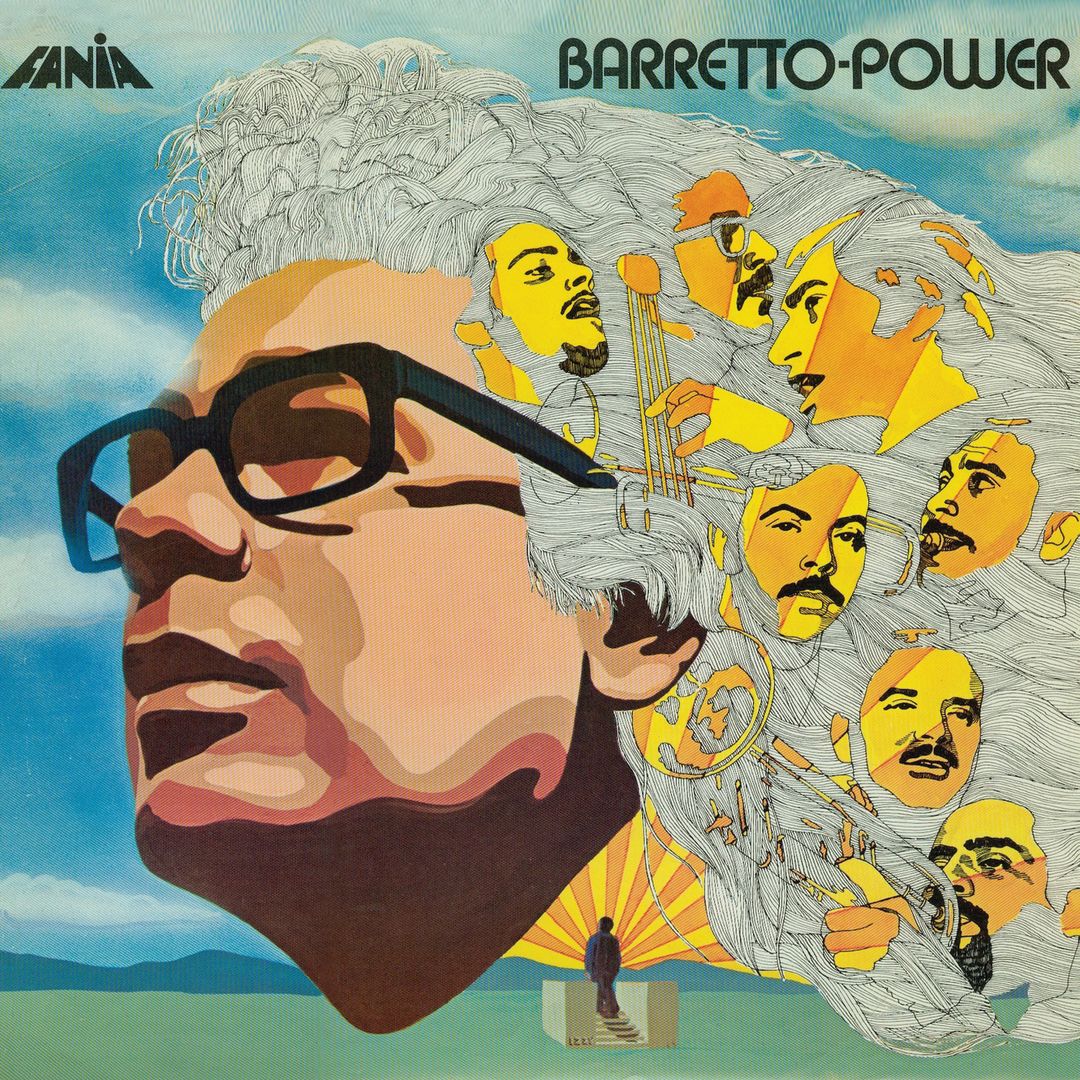

Ray Barretto’s 1970 LP Power, also designed by Sanábria.

Image: Courtesy Photo

Classic Sanábria album designs include legendary percussionist Ray Barretto’s 1973 Indestructible, featuring an indestructible Barretto on the cover, exposing his hidden Superman side under a seemingly ordinary Clark Kent outfit; and singer-songwriter Ismael Miranda’s 1970 Electric Harlow, which highlights Sanábria’s unique lettering technique overlaying a photo of a moody young Miranda with pianist Larry Harlow behind him. Generations of kids grew up with stacks of these iconic LPs around the house, the vinyl spinning while they danced with their abuelas on cleared-out living room floors.

Salsa—both a dance and a musical style—surged in popularity in the 1970s, primarily through the immigrant diaspora dancing to the fusion of the new sounds of Caribbean and African beats with jazz rhythms. At the start, this confluence of styles was simply referred to as “Latin music,” but Sanábria began using the term “salsa” in early issues of Latin N.Y. magazine in 1973. At the time, Sanábria was an artist and media Renaissance man. He created artwork for the genre through album covers and event posters, he oversaw Latin N.Y., he hosted a show called Salsa (a Latin version of Soul Train) and he hosted the first Latin N.Y. music awards.

“I thought outside of the box and fought tooth and nail to get [the word] out,” Sanábria says. “Promoters weren’t ready for it until the all-important 1975 Latin N.Y. music awards.” That ceremony was born due to the lack of representation for salsa music at the Grammy Awards. Sanábria gave the opening remarks to a crowd at the Beacon Theater.

“Salsa is the sound and rhythm we breathe, the rhythm we live by and the rhythm we make love to,” he said. “At a time when salsa is ready to explode nationally, it is being choked. Some people call it ethnic, primitive, savage and even vulgar. I say Latin music is all that and more. The same thing was said of the Charleston. The same thing was said of ragtime, jazz, swing, rhythm and blues, rock ‘n’ roll and even opera.” The crowd erupted with cheers and whistles at the end of each line.

“No one else has his history and artwork,” Montenegro says, “nor his 20 years with Latin N.Y. magazine.” The magazine was published from about 1973 to 1985 and catered to New York City’s bilingual community, filling a need for second-generation immigrants who were moving away from the language their parents spoke.

Sanábria’s lettering artwork quickly became iconic, influencing graffiti artists. “My inspirations were from the Bible, Salvador Dalí and underground artists involved in illusion art,” Sanábria says. “My whole goal was to provide the Latino community with quality in the artwork and improve the image of Latinos, period.” In 1977, Sanábria met his hero, Dalí, and the two ate dinner together at a friend’s restaurant.

Sanábria says he learned important skills from New York’s School of Industrial Arts, a hospital-turned-high school. You can almost hear his grin as he shares how he learned printing processes for posters and album covers.

“I would start the original in black and white, afterwards applying layers of color to achieve different tonalities,” Sanábria says. “I had a particular skill no one could do at the time, with linear artwork, drawing lines very close to each other.” Early on, Sanábria was drawn to album covers. He says they act as a physical representation of music for people who haven’t heard it yet, and the images document salsa’s growing popularity and the rising influence of Hispanic and Latino cultures.

In 2019, Montenegro reconnected with Sanábria via Facebook. The two zestful contemporaries got together with their wives and have kept up a friendship since. Many know Sanábria today as the “Salsa King.” And yet, the genre’s history and Sanábria’s role in it are at risk of being forgotten. For Montenegro, it’s imperative to share salsa music and the culture around it with younger generations.

Sanábria’s influence will never wane as long as people keep spinning salsa classics, which are a staple at places like Sarasota’s Rincón Cubano and “Latin Nights” with DJ Nando at the restaurant Nicky’s, which are slowly bringing back the energy, artists, music and space for people to practice their bachata, enchufa or New York Walk. Bulking up the offerings of salsa music and history are the Historic Asolo Theater, Latin Quarters, Art Ovation Hotel, Motorworks Brewing and Fogartyville Community Media and Arts Center.

You’ll also hear salsa at Sarasota’s DK Dance Creations, a dance hall co-owned by Kery Fernandez and Darío Hernandez. Fernandez, 39, identifies as Hispanic by race and Dominican by nationality.

Fernandez is committed to teaching salsa beyond just the steps. Like with Montenegro’s show, she wants to offer a full historical education about the dance and the music. Her passion led to the creation of the Sarasota Salsa and Bachata Festival, which is about to enter its third year in September and which brings top dance instructors to Sarasota for three days of workshops, masterclasses, pool parties and what Kery calls “all the Latin dancing your body can handle.”