The Gods and Lovers Exhibit at Ringling Magnifies Indian Art

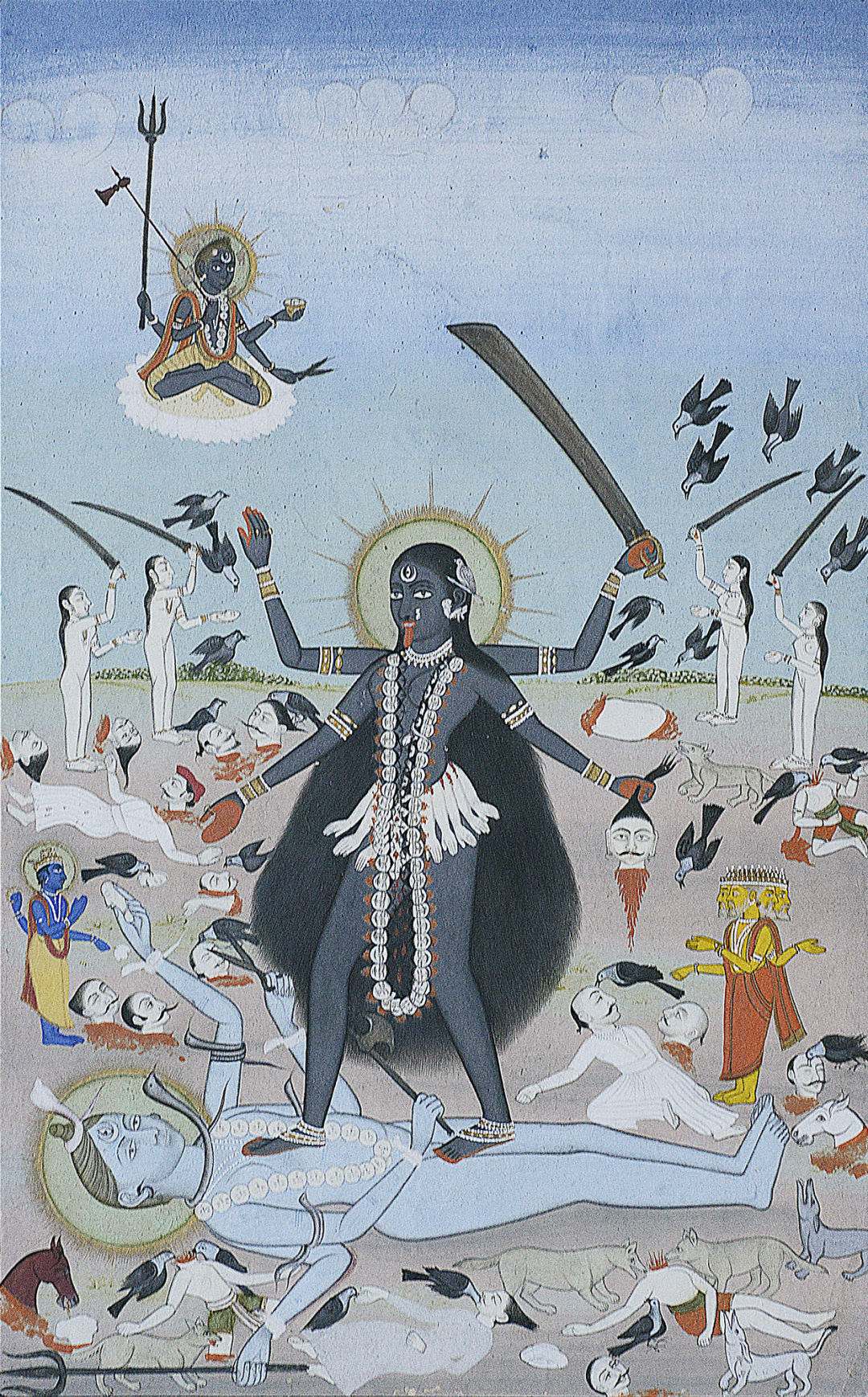

The Goddess Kali in the cremation ground, ca. 1850, is on display at the Gods and Lovers exhibit at The Ringling Museum.

Experiencing the Gods and Lovers: Paintings and Sculptures from India exhibit at The Ringling Museum is like playing a life-size game of "I Spy." Throughout the gallery, paintings offer vibrant colors and mesmerizing details—many so intricate that a magnifying glass is needed to spot them.

However, Dr. Rhiannon Paget, curator of Asian art at the Ringling Museum, is happy to share a 21st-century trick with visitors eager to immerse themselves into the world of 17th- to 19th-century Indian painting. “We assume that people used magnifying glasses back then, because they wore eyeglasses, but visitors can zoom in with their smartphones to spot the paintings’ sophisticated details,” she says.

At the entry point to the exhibit, a large map of South Asia helps visitors get their bearings, highlighting the regions where each work originated. Nearby, a family tree-style diagram of the Hindu deities and their relationship to one another introduces guests to the gods, goddesses and other divine characters they’ll come upon throughout the gallery. All are encouraged to snap photos of the map and diagram, then use them as an art history cheat sheet while perusing the works.

The majority of the pieces reflect Hindu themes, but there is one piece from the influential Muslim Mughal Empire, which encompassed areas of Northern India from the 16th to 19th centuries. “Aspects of the Mughal style disseminated when artists moved from Mughal courts, then migrated to different regions of India, leading to an exchange of artistic techniques,” Paget says. As a result, paintings from across the continent share similar characteristics, like the custom of painting on paper, a contribution of the Mughals. (Before paper, artists were painting on walls and palm leaves.)

According to Paget, the Hindu paintings were commissioned for personal intimate viewing by the ruling classes of princely states. They were status symbols as well as devotional objects because meditation on the exploits of the gods, who often appear in the paintings, was considered a form of devotion.

Workshops, or artist collectives, generally led by a head artist who supervised a team, created the paintings. “Most of the time, we don’t know the names of the artists who produced these paintings as they weren’t usually signed,” Paget says.

These anonymous artists created the works on paper, using ink as well as water-based mineral and vegetable pigments. Minerals from stones like brilliant blue lapis lazuli were mixed with animal-derived glue to form the paint pigments. Artists also favored radiant gold leaf and used a stone-rubbing technique to add shine and cement the pigments onto the paper, creating a bold, eye-catching effect.

“The paintings capture enthralling stories from Hindu scriptures and epics, themes of romantic love, power struggles and stories of good triumphing over evil,” says Paget.

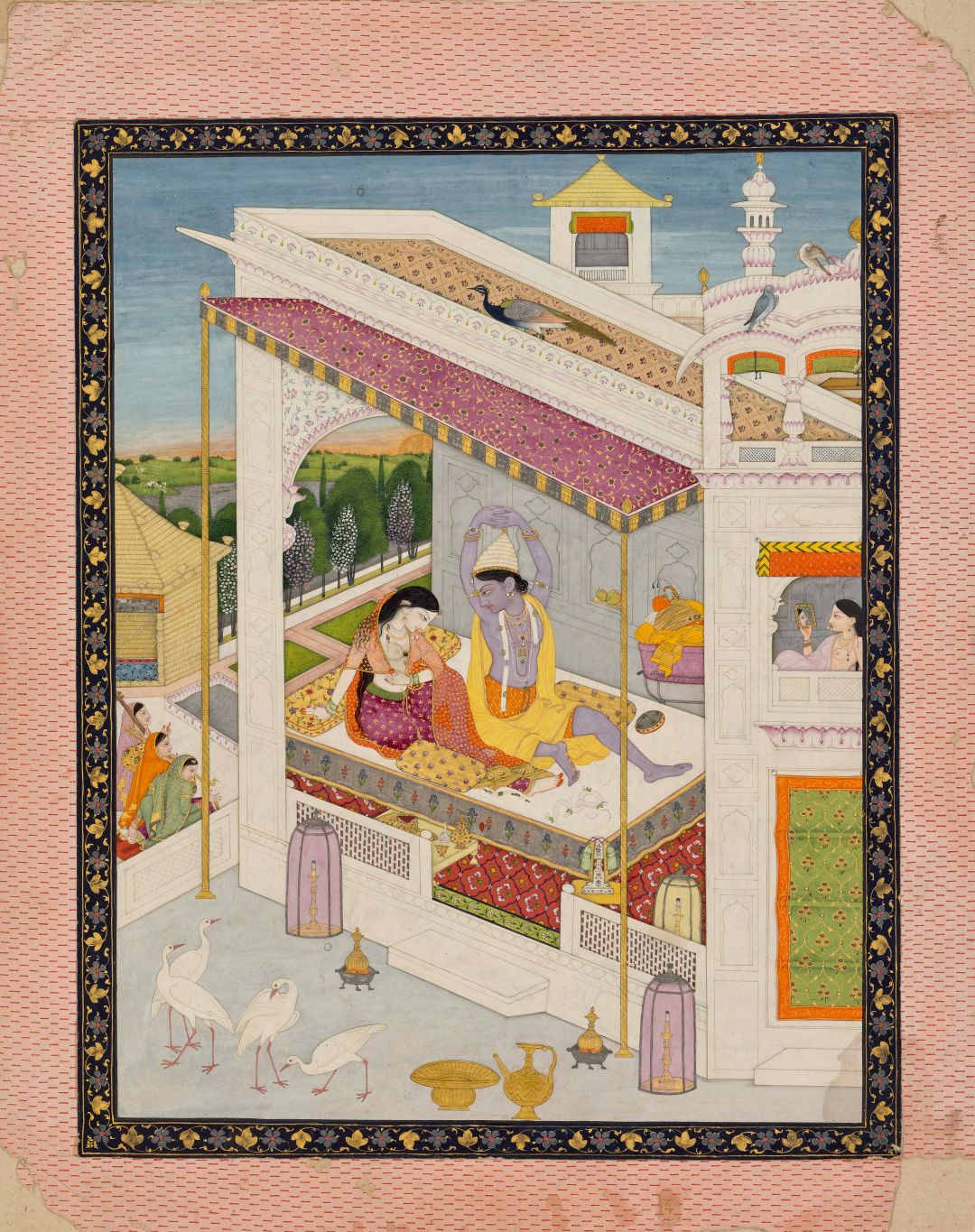

Krishna and Radha on the bed waking up to music

Image: Courtesy Francesca Galloway

One painting, from Himachal Pradesh in Northern India that was created around 1800, embodies the exhibit’s title. Underneath the morning sky, divine lovers Krishna and Radha relax in bed after a passionate night together. “It’s tender and erotic,” Paget says, “and I love how the artist captures charming details, like broken jewelry on the bed.” A closer look reveals nearby birds and a neighbor admiring herself in a mirror.

Indian painters’ shrewd observational skills and ability to create art that reflected their culture are also on prominent display in the exhibit’s ragamala paintings, or "garland of ragas." These works visually represent popular Indian melodies, known as ragas, which are meant to elicit a certain mood and color, and are often meant for listening at certain points of the day or times of year—there are morning ragas and evening ragas, for example. According to The Metropolitan Museum, “the unifying subject of a ragamala is love, which is evoked as a range of specific emotions … that have a corresponding musical form.”

One ragamala features a prince playing a stringed instrument with one lady standing in front feeding him while he plays as another feeds a peacock. From a contemporary perspective, the process is akin to creating a painting that illustrates one’s favorite love song. In fact, Paget suggests listening to a raga to enhance the viewing experience.

In addition to the paintings, Hindu, Buddhist and Jain sculptures from the 4th through 15th centuries offer a glimpse into other religions practiced during the period. The statues range from marble Hindu deities to a brass and copper shrine. Visitors can also check out other Indian statues from the neighboring permanent collection.

“This is a rare opportunity to see a truly superb group of objects without having to travel to a large city,” says Paget, “and the exhibit opens up an exciting world of narratives for everyone to learn about the rich culture of India.”

Gods and Lovers: Paintings and Sculptures from India is at the Pavilion Gallery of the Ting Tsung and Wei Fong Chao Center for Asian Art until May 28, 2023. Indian art enthusiasts can also attend the Gods and Lovers: Hindu and Muslim Paintings from Courtly India, 17th to 19th Centuries lecture at 11 a.m. on Dec. 8. Entry to the exhibit is included in general admission. For ticket and pricing information, click here.