Yes, Sarasota Has a Rap Scene, and It's Loaded With Talent

Driving on 15th Street, west of Tuttle Avenue, you wouldn't know you were passing by one of the focal points of the Sarasota hip hop scene: Sota Studios, a hub for a collective of artists, producers, photographers, videographers and more. Located in an unadorned strip in the city's industrial area, among little-used warehouses, car part graveyards and swaths of yet-to-be-developed land, Sota is hidden behind a series of nondescript doors that resemble a roadside motel.

When I stopped by this summer, the familiar smell of incense and various roll-able, smoke-able leaves washed over me like an old friend. Inside, I found Sidney—aka Sidney Austin, a 23-year-old born and raised in Sarasota who, along with Swerv the Hooligan and Tre Godfella, formed a rap crew that goes by the name IIIMPERIAL.

Sidney is a student of the genre and cites his influences as primarily West Coast artists like Kendrick Lamar and his former labelmates at Top Dawg Entertainment, Nipsy Hussle (who was shot and killed in 2019) and even MC Eiht, a rapper with a distinct and sticky voice who told stories about West Coast struggles and neighborhood life. For Sidney, the storytelling of West Coast artists is relatable to what's going on in Florida—"the sun, the beaches, the women, gun violence, drugs and how it affects the youth,” he says. His crewmate Tre rhymes, introspectively, on their standout single "Westside Terror": "My ego is colossal, my shrink say that I'm self-absorbed / Shit, you’d be, too, if you witnessed thе shit that I endured."

Sidney's mom worked as a custodian and lunch lady in area schools, and his dad is a landscaper on Lido Key and does custodial work, as well. But it was Sidney's father's passion for music that inspired him as a child. "My pops was a DJ,” says Sidney. “A lot of older people—we call them the old heads—in my neighborhood really know my pops. They drive by and see him and wave and be like, ‘’Sup, Yac,' because he went by DJ Super Yac back in the day. I have vivid memories of growing up and hearing records. He was my first taste in music."

The Isley Brothers, the Commodores, the Jacksons, disco and Parliament-Funkadelic all soundtracked Sidney's childhood. He remembers getting a drum set for Christmas, which led him to hip hop because, as he says, "hip hop is based around rhythm.” He started writing raps in middle school and became part of an emerging community of aspiring artists when he was a student at Booker High School.

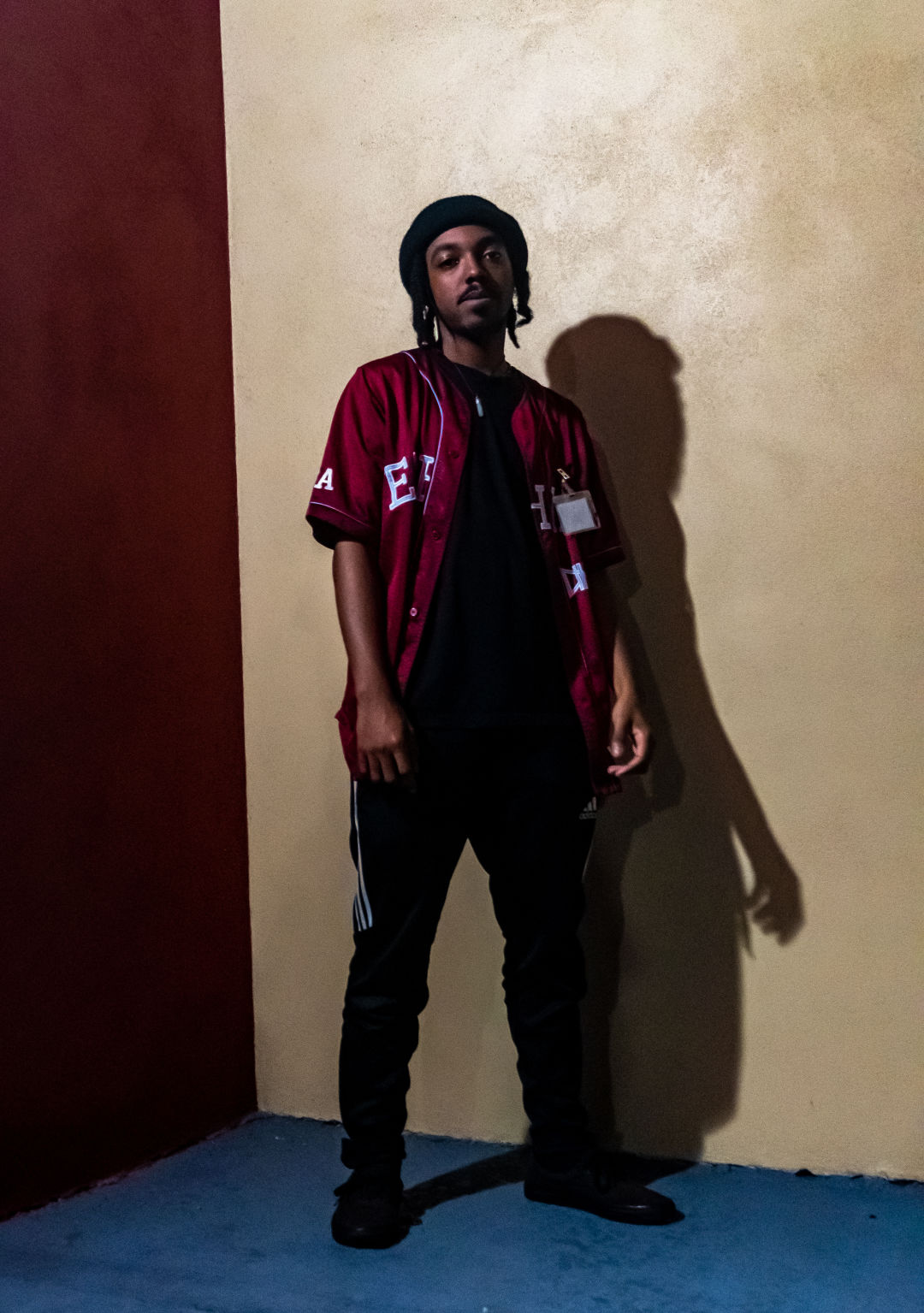

Sidney.

Image: Michael Cairo

That’s where he met Swerv the Hooligan and Tre Godfella. Sidney's friend Josh is Tre's younger brother, and as Josh began to see Sidney develop and take his craft more seriously, he introduced him to his older brother at an open mic. Swerv was there, too, and after seeing one another show and prove that night, the trio began to spend time together recording music. It's "diamonds sharpening diamonds," says Sidney.

IIIMPERIAL’s debut record, IIIMPERIAL x STYLES, came out earlier this year. It's a joint album that was made with Sarasota producer and artist Forenzik Styles. On it, you hear the distinction in each rapper's ability. Although there is a nostalgic boom-bap sonic bed these MCs find themselves rhyming over, the group feels fresh and of the moment. You hear that especially in Sidney's sing-song raps on "Secrets," a slower, soulful song that is similar to Houston's chopped and screwed sound. His playful, relatable rhymes are endearing and confessional like an I.G. reel. "Ain't no limits to the sky / Ain't no secrets to me," he raps. "Ain't nothin' special to see / Ain't no secrets to me / I wash my hands in the sink."

IIIMPERIAL x STYLES was the first record the group took seriously—more than just a hobby pushing mixtapes in their friend groups. There’s a polished professionalism to the album that Sidney also exudes, even at just 23. The project, he says, was an opportunity that "draws a line between artists that want to do this and artists that are just doing this.”

At Sota, when I ask Sidney about where hip hop lives in Sarasota and Manatee counties, he smiles confidently and laughs. "You are actually in the right place,” he says. “This is the launchpad right here.”

Hip hop is ubiquitous. What originated in the early 1970s as an underground, countercultural art form created by Black and brown teenagers in the deindustrializing boroughs of New York City has spread everywhere—from the most rural spaces to suburban malls, from TikTok to insurance commercials. Almost 50 years into its existence, hip hop continues to be a growth industry, responsible for influencing culture and economies around the globe.

But as the commercialization and commodification of hip hop continues, millions of young people all over the world still seek it out as a tool to air their innermost thoughts, desires and fears, documenting their experiences and neighborhoods and, of course, using it as an outlet to turn up, have a good time and celebrate themselves and their friends.

I moved to the area last year from Chicago, where I was privy to witnessing the growth and development of Chicago's hip hop scene, from Kayne West to Chance the Rapper. When I set out to see if there was a hip hop scene in Sarasota and Manatee counties, I was pleasantly surprised to encounter a vibrant, talented and varied community that might not be on the radar of most residents. Yet.

When most of us are asleep or working our day jobs, there is a growing mix of young, independent artists engaged in a DIY entrepreneurial approach to music- and space-making. In forgotten storefronts, bedroom studios and reconfigured garages, there is a growing network of young people, 19 and older, who are telling their stories and the story of a generation that, for some, might be difficult to hear. But it’s the kind of realist, nuanced and highly stylized reportage that hip hop has spent the last five decades creating.

Ryan "Ryanito" Larrañaga.

Image: Damon Powers

At 35, Ryan "Ryanito" Larrañaga is kind of an O.G. of the local scene, with an impressive discography and global performances under his belt. In 2020, he completed a European tour and is currently working on an album with features from highly respected artists as The Game, Styles P, Twista and Devin the Dude.

He comes from a musical family. His mom loved Motown and his cousin put him on to artists like Rakim and KRS-ONE when he was just a kid. Ryanito fell in love with writing and lyricism, using highly dexterous wordplay in songs like "There I Go" from 2017's Cosmic Guide, in which he rhymes, "Money corrupts the minds of men, then we blinded to the mission / Preach the possibilities and reap the karmic benefits / To put it in perspective, the tears I have mended / When Moses part the sea of this beat, then I descended."

When Ryanito moved to Sarasota from Maryland in 2009, "the scene here was very club-based,” he says. “There wasn't an all-around scene. The demographic wasn't completely receptive to hip hop. The expectation was for people to play cover songs. There was still a pushback. Everywhere we would go, it'd be like, 'Oh, not these hip hop guys.’”

Out of ingenuity and necessity, Ryanito started to throw events in 2012 with DJ Cellus, a Sarasota-based cultural organizer he met at Fogartyville Community Media and Arts Center. They had a successful night dedicated to street art, rhymes and beer at the now-shuttered JDub's Brewing Company, and together threw a concert at which Ryanito was accompanied by a full orchestra. Since that time, Ryanito has pulled back from the public scene in order to focus on raising a family and recording music.

When I ask about the local scene now, he says, "I don't think there is a local hip hop scene. There is a mentality here that as long as you make it in on your block, as long as your mixtape goes out to your best friends, you've done it. And for me, that's not the mentality."

Before bunkering back down into his studio to finish his latest project, Ryanito introduced me to his longtime collaborator: singer and actor Michael Menendez. Menendez was born in the Dominican Republic and raised in uptown Manhattan. Now 30, he has been in Sarasota since he was 15, and is a veteran of the arts community who has made a living as an actor and production assistant with the Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe.

Menendez was introduced to hip hop and studio engineering by his uncle in New York. When he came to Florida as a teenager, he started to attend local house parties, finding his way, socially, in the arts scene. "Sota and Slim Figga, Drummerboy Studios and EJ Porter were a guiding light to what hip hop was in the area,” he says.

Menendez graduated from Bradenton’s Bayshore High School, where he took a "rap class" with a choir teacher and ended up singing hooks on his classmates’ songs. He remembers a time when Sarasota was "a C-class circuit" in the world of traveling regional acts, when artists like Gucci Mane, Plies (who was born in Fort Myers) and Lil Jon all played in the area. "The Hall was a big venue that moved from Bradenton to Palmetto and eventually closed,” says Menendez. “Hip hop then migrated to the strip clubs.”

Menendez and I met at The Mable, a dive bar with a small stage in the corner that hosts a Tuesday open mic. "The problem with hip hop in this area is that the venues stopped supporting,” he says. “There were no venues to grasp the next ’hood star or the next intellectual lyricist.” The Mable is trying to become a home for what Menendez calls "marauding lyricists looking for a place" to perform. "There is something that is trying to come out of here,” he says.

An open mic is essential to the ecology of a local music scene. They provide a regular venue in which artists can hone their craft as performers and build and find a fan base—a night in the week that pushes artists to create and share new material and gives them a chance to establish a community and network of other, like-minded artists who can become potential collaborators.

The Mable's open mic seems to get going somewhere between 9:30 and 10:30 p.m. The night I attended, there were around 30 people—maybe more. The sound was overpowering and complicated by technical difficulties, making it difficult for the performers, but perhaps also instilling in them flexibility and improvisational skills, all things necessary to finding success.

The night was more alt-rock cabaret than the hip hop center I was hoping to find. But then a skinny baby-faced boy in a pink knit beanie got up and plugged in his phone to provide a backing track over which he melodically rapped about heartbreak and depression. He was almost screaming, but in remarkably controlled, dulcet tones: "I don't love you / And none of your friends.”

Short Term.

Image: Courtesy Photo

The singer-slash-rapper goes by Short Term, "like memory," he told me as we stepped into the Mable parking lot after his six-minute set. He is 23 years old, from Racine, Wisconsin, and moved to the area recently because of the music scene and because his buddy had a couch to share.

Short Term is working three jobs. He manages a coffee shop, waits tables and is a social media manager for other artists. His goal is to have music pay his bills, but for now he carves out time, when he can, to write, record and perform. He told me he became addicted to pills at 15 and got shot at for stealing from a drug dealer. His music provides an outlet for him to wrestle with demons and reflect on depression and drug abuse. He's performed at The Mable’s open mic a few times since coming to town and has gotten a warm reception. "The Mable is an escape from reality," he told me before heading back inside to support the other performers.

For decades, hip hop was firmly rooted in a locale. Rappers often shouted out familiar corners, crews and people in their neighborhood that were typically neglected on the 10 o'clock news, unless some tragic event occurred. But with the dawn of the internet, hip hop began to circumnavigate the music industry’s traditional gatekeepers—big music labels and media outlets—in order to connect with fanbases both local and global. When I was kid looking to find a local hip hop community, I'd have go to an independent record shop and pray there was a flyer that had an address for a house party. Hip hop was an insider and underground forum, where you had to know somebody who knew somebody to be in the know.

In 2022, "the streets" have become the internet. It was by Googling and hashtagging my way around that I found IIIMPERIAL and Sota Studios.

I asked Sidney about other venues that host hip hop shows.

"Spaces around here are a little biased against hip hop, because hip hop tends to attract a younger crowd and there is a younger crowd that might be a little rowdy and might want to stand out in the parking lot and drink or smoke or whatever,” he says. “But if you look at the history of rock and roll, was it any different? How many people were drunk at venues for rock concerts that are still probably doing that in Sarasota, to this day, when cover bands come to town?"

He continues, and, as much as I like Sidney as an artist, I feel he could also run for office.

"There are a multitude of young people here, of all different age groups, adolescents to teenagers to where we are, in our early 20s, looking for things to do,” he says. “They took away the Stardust [a now-closed skating rink] and the kids don't have nothing to do. Payne Park is being regulated so much they barely want to go there now. There is a racial divide that is slowly being blurred with hip hop, but the older generation is not getting it, because they don't like the sound of it or they don't like the structure of it, so they are like, 'No hip hop here.'"

But there is one venue in Bradenton, Sidney told me, that opened recently and is dedicated to photography and videography and is starting to throw shows. It's run by a promoter and videographer, Jean, who goes by Deadsoul Entertainment on Instagram. Gene has filmed a number of videos for local rappers and is trying to create a space for the scene to flourish.

Base, the venue Sidney sent me to, is a multi-use, all-ages space in a strip mall. I arrived on a Saturday night for an event called Noisy Street 2 and discover that “all-ages” is very literal. There were grandmothers and shorties just cracking double digits who were running around way past their bedtime. Overall, the crowd was young, diverse and fly. A young man with bleach-blond dreadlocks, a James Harden jersey and a gold grill sat on the stage, his dental adornment reflecting the venue's strobe and stage lights.

There was an undeniable energy and underground spirit. There were Styrofoam cups, blunts, Bucs jerseys and thrift store T-shirts. The sound system needs some work; there was just not enough amplification to fill the space, and the feedback and reverb from the microphones reminded me of punk shows. But there was an impressive and massive list of artists slated to perform, and everyone had six minutes.

Big Pe$o.

Image: Michael Cairo

One of the artists associated with Sota Studios, CCG WVDE, moved to the area four years ago from Fort Wayne, Indiana, because "there's more opportunity here,” he says. His frequent collaborator, Big Pe$o, is 25 years old and has a date of import tattooed above his right eye. He brought two of his younger brothers, 12 and 11, with him to tonight's show. They are also rappers, backing up their older sibling on stage. It's adorable.

Another standout was 2klips, who asked the crowd if he was clean, and they affirmed with a frenzy of screams as he bounced around the stage with a flurry of melodic, high-energy rhymes. Florida hip hop can be thematically redundant, the sound fluctuating somewhere between Pompano Beach's Kodak Black to St. Pete's soul-rap juggernaut Rod Wave. Not every act at Base was outstanding, partly due to a series of equipment malfunctions and partly because many of the acts don’t have consistent stages on which to hone their skills. Some of the content also felt like iterative tropes out of a rap-by-numbers book. Songs covered a bevy of belabored topics like money, weed and women.

But there was something there—a blend of textures and styles. "The Sarasota sound is more like adobo or Creole seasoning," Sidney told me as he prepared to hit the stage with Tre. (Swerv the Hooligan, the third member of IIIMPERIAL, was at the hospital for the birth of his daughter.) There was so much talent and style in that room, I felt like I found at least one place where hip hop is thriving.

Sidney and Tre took the stage and commanded the mic and crowd like veterans. They were engaging and in sync, backing each other's vocals to emphasize certain words like exclamation points. Sidney called up friend and studio mate Bilooshey to perform their song “Creep,” from Bilooshey’s brand new EP, That's the Dog in Me.

Sidney and Bilooshey passed words back and forth like they were juggling: "No, I'm not rich, but honestly livin' comfortably / To understand myself and what the fuck I wouldn't want from me / Thinkin' 'bout a tat I need that sting like a bumblebee." They were young and energetic—firmly in the tradition and also a bridge to the future.

I was standing in a corner of the venue most of the evening, trying to survey the crowd, take in the music and get a chance to talk with some of the folks, both on stage and in the audience. At some point, Tre Godfella, a gentle giant, tapped me on the shoulder. He was surprised I was standing next to him. "You're the most in-the-cut dude I've ever seen," he told me. I took it as a high compliment.

Tre Godfella.

Image: Michael Cairo

I felt seen and celebrated by Tre, something he was known for in both the hip hop and broader Sarasota and Bradenton communities. "If you got a goldfish or a big gig, he was a cheerleader," says Swerv, one of his best friends. Shortly after the show at Base, on Aug. 23, Tre, aka Travian Davis, died from an epileptic seizure, one of many he had experienced in his life. He was only 28 years old.

Four days after Tre's death, I attended a candlelight vigil in Newton Estates Park that his friends and family organized to mourn and celebrate his life. There were well over 60 people there—Tre's family, other artists, fans and coworkers from Lowe's, where Tre worked. They battled the wind to keep their candles lit as the sun set in the west and the mosquitoes started to bite. Some swore it was Tre having a big laugh, as he was accustomed to do, his spirit participating in the celebration.

Swerv says IIIMPERIAL is sitting on so much music that Tre would want to see out in the world. At the time of his death, Tre was finishing up a solo project and another group record, so IIIMPERIAL and Tre's voice and stories will continue to find an audience and community. "There is a bond that is going to be there forever," says Sidney. "I don't think the group is finished. Not at all." Everything felt so raw and so sudden, but the work and artistry will continue, now in the light and legacy of Tre. "We need a community," Swerv told those gathered in the park.

If hip hop in Sarasota is really going to take off, it needs more places in which artists and fans can connect. That’s one of the reasons why Sidney has built Sota Studios and continues to create music here and make space for other artists to do the same. "I am just trying to figure out how I can take it to the next level,” he says. “Not only for me, but for the whole city.”

Kevin Coval is an Emmy-nominated, award-winning poet, playwright, author, screenwriter and editor of more than 10 collections and anthologies including The Breakbeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip-Hop and A People's History of Chicago. He is a creative consultant and founder of Breakbreat Creatives, and his writing has been featured on/in The Daily Show, NPR, The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Source Magazine, Slam and WSLAM, Rock the Bells, CNN.com, four seasons of HBO's Def Poetry Jam and more. He currently lives in Sarasota.