Eight Sarasotans Who Shaped Our Past

This is our 40th anniversary year, and I have been Mr. Chatterbox for 34 of them. I had a privileged seat at the table to watch Sarasota become what it is today. And while I was at that table, gorging myself on yet another dinner in the ballroom at Michael’s On East, I listened. You can learn a lot of things if you keep your mouth shut.

Mostly I heard about people. Sarasotans love to talk about people, particularly when the people they are talking about are just out of earshot. Oh, the stories I heard. Some of the characters being dissected—I mean, discussed—were famous names, at least in this town. Others are just dimly remembered. Others aren’t remembered at all. Some of these stories I told in my column. But there are other stories, stories I’ve never told—until now.

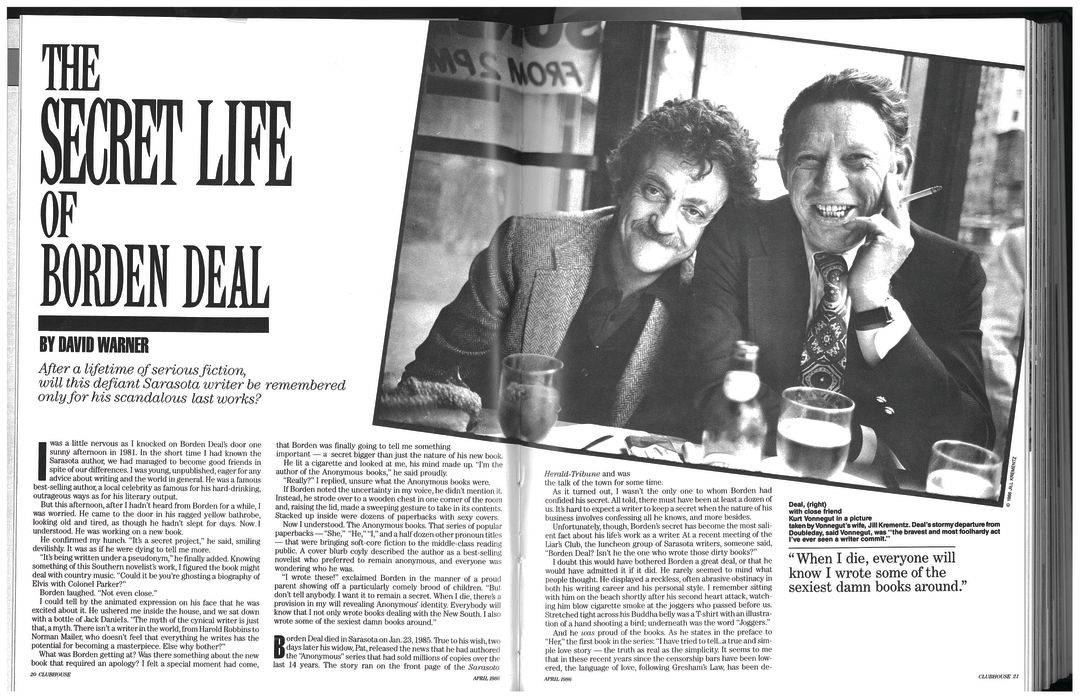

A 1986 Sarasota Magazine story shows Borden Deal, right, with novelist Kurt Vonnegut.

Image: Staff

Let’s start with Borden Deal. He lived here during the tail end of the artist colony era, when Sarasota attracted prominent writers and painters who came to create. (They still do. Stephen King is currently creating on Casey Key.)

Borden Deal was no Stephen King, but he had a run of success in the 1950s and ’60s. He specialized in novels about the “New South” and its changing ways. They dealt with subjects that seem odd by today’s tastes. Interstate is about the interstate highway system and Bluegrass is about breeding race horses. One of them tells the story of the Tennessee Valley Authority and became the classic movie Wild River, starring Montgomery Clift and directed by Elia Kazan.

By the time he moved to Sarasota in 1964, Borden was the epitome of the hard-drinking novelist, full of braggadocio and always chasing women. He would embarrass himself in public, like the time he dragged a titled Englishwoman, here for a gala, out on the dance floor and forced the poor woman to perform a rumba. Even today you hear gossip about his one-night liaisons with otherwise proper ladies of the social set.

By the 1970s Borden’s career was slowing down. Tastes were changing. He became more cantankerous, and his books weren’t getting published. He went as far as picketing his publisher’s office. Most days were spent in his bathrobe, working and drinking and suffering health problems brought on by his many excesses.

Yet he always seemed to have plenty of money. He even bought his daughter Shane a nice house on Datura Street. Where was it coming from?

The mystery was solved two days after Borden died of a heart attack in 1985. A statement was released. Borden Deal was not just Borden Deal. Borden Deal was Anonymous.

Every era, it seems, has its very own sensational sex novel, and as we have Fifty Shades of Grey, the 1970s had the Anonymous books. There were nine of them, each with a one-word title. Her was the first, followed by Him, then Them, etc. They were simplicity itself. A frankly described sexual affair occurred—and that’s about all. They were wildly popular and sold millions of copies.

Exactly who Anonymous was became an object of much speculation. The PR made it clear that he was a successful writer who didn’t want to damage his literary reputation. Ironically, Borden became rich and famous as Anonymous, while Borden Deal remained a broken-down novelist who couldn’t get published. He was one of the most successful writers in the country—but no one knew it.

Today neither Borden Deal nor Anonymous is read much. The world has moved on, and few people remember them. Borden lives on indirectly through Wild River, and as for Anonymous, well, I have a feeling that a few elderly ladies over at Plymouth Harbor may be blushing as they read this.

Dale Murray, right, with business partner Richard Genth in 1984; inset, one of Murray’s Chris-Craft speedboats.

Image: Staff

Our next face from the past is certainly worthy of a novel. He’s the classic Sarasota archetype—a rich man who blows into town, buys a flashy house, impresses everybody, becomes a major player, then crashes and burns.

Dale Murray grew up an orphan in the hills of Kentucky. But he was smart, and by the time he was 40 he had made millions buying up old coal mines and making them profitable. Now he was ready for something a little more glamorous.

He used his coal money to buy 90 percent of Chris-Craft, the famous powerboat manufacturer. He then relocated the company plant to Bradenton and himself to Sarasota, where he bought a mansion in Lido Shores.

Murray reinvigorated the company with innovative designs. Sales increased sixfold in a matter of five years, a fact partly attributable to the hit TV show Miami Vice, which featured the company’s Stinger model. The image of a Stinger speeding across Biscayne Bay captured a new image for stuffy old Florida—glamorous, rich, sexy, with a heavy whiff of crime and danger in the background.

Murray’s own life reflected this image. He would go out to dinner in a helicopter, which would land in the vacant lot next door to his mansion, much to the annoyance of his neighbors. His business associates were among the most powerful men in the country. The Chris-Craft board included F. Lee Bailey and Alexander Haig.

It was when Murray looked outside the country for refinancing that his troubles began. He sold part of the company to Ghaith Pharaon, a Saudi billionaire and arms dealer who was involved in the BCCI financial crisis of 1991. Now things took a darker turn. Murray’s company designed super-fast boats for the Colombian drug cartel. The U.S. government found this out, and, to save his neck, Murray made a deal to build even faster boats for the Coast Guard. The cartel discovered the double cross and put out a contract on his life.

A tour of the Murray house today reveals the elaborate security measures the FBI took to protect Murray. In addition to cameras and a 12-foot-by-12-foot concrete bunker-like room with a bank vault door, there were agents on guard 24 hours a day. Local legend has it that the Colombians showed up one night—by boat, of course. Shots were fired, but the assassination attempt came to naught.

But Murray had become toxic, businesswise and socially. Chris-Craft went bankrupt, and Murray lost everything. He moved back to Kentucky and tried to re-enter the coal mining business. But bad luck dogged him at every turn. In 2002 he was sentenced to a year in prison for failing to support the out-of-wedlock daughter he had with a topless cocktail waitress. To quote the judge: “The trial testimony reads like a Greek tragedy. There are staggering amounts of money made and lost. There are hubris, power and influence, international intrigue, betrayal, and an extramarital fall-spring love affair.”

All that’s left of Dale Murray is the famous house in Lido Shores. It was built by Phillip Hiss, the driving force behind the Sarasota School of Architecture, as his family home. Then a gay French count, who gave glamorous parties around the pool and decorated the house with—shall we say—provocative sculptures, owned the place. Then the French Gardinier family, which owned the phosphate company that has since become Mosaic, bought it. Today it’s owned by a family from Indiana so rich they have a university named after them. Singer Bobby Vinton also lived there back in the early ’90s. He left behind his drapes. They’re still there. And yes, they’re blue velvet.

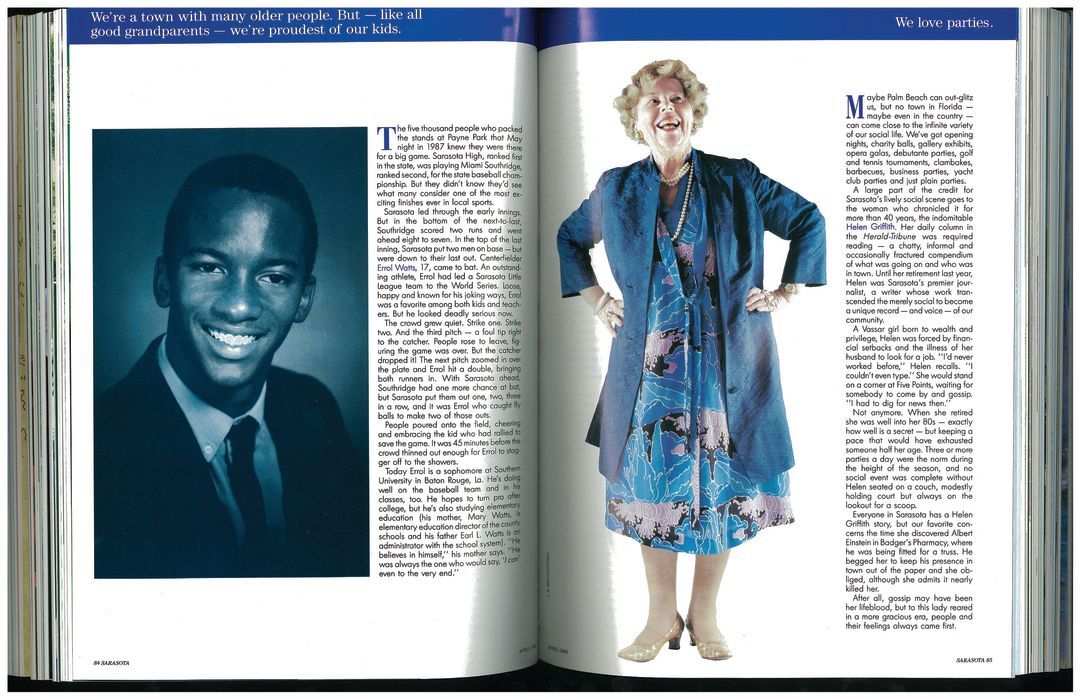

Helen Griffith in an April 1989 Sarasota Magazine story.

Image: Staff

Wonder what Helen Griffith thought of Dale Murray and the new people. She’d been writing her column in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune since 1945 and had interviewed everybody but Einstein—wait a minute, she interviewed him, too—but by the mid-’80s she was seeming a little old-fashioned. The paper even got the woman’s page editor (yes, there used to be such a thing) to write a column geared toward the “younger set.” That woman turned out to be Marjorie North, who did such a good job that she became a local legend.

But Helen was also a legend, and she would be the first to point that out. Her column was loquacious and sometimes quite charming. She talked about the weather in poetic ways. She would recount bumping into a friend from Tampa at Five Points and let you know that the so-and-sos were here for the winter and they were staying at the such-and-such hotel. I remember seeing a column she wrote in 1959 congratulating “local writer John D. MacDonald” on selling an article to a magazine called Motor Home Owner.

Helen worked well into her 80s, by which time she wasn’t as sharp as she used to be. Sometimes her dresses were on backwards or inside out.

When she died in 2003, her daughter Joan told me the attendance at her funeral was “underwhelming.”

Joan Griffith

Image: Sarasota Magazine Archives

Joan Griffith was Sarasota’s Blanche Dubois—a willful, fragile person who dreamed big and was always disappointed. As a teenager she was what they call “boy crazy,” and any celebrity who came to town and was interviewed by her mother was fair game.

Joan graduated from Sarasota High in 1949 and immediately left for New York. She worked as a model, showgirl, movie extra and lounge pianist until she discovered her real talent was for writing. She began to “feed” material to Walter Winchell and wrote jokes for TV personality Robert Q. Lewis, a name that may still ring a faint bell for very old baby boomers.

She also tried her luck in Hollywood, but real success kept eluding her. When she moved back to Sarasota, this time with a daughter in tow, everybody was too embarrassed to ask for any details.

Joan’s writing career in Sarasota lasted 30 years. “I can write in any style,” she boasted, “even quatrains.” Her work moved at a lively pace, fueled by binges of caffeine and God knows what else. Her mistake was, perhaps, to attempt social columns like her mother. She was not popular on the social scene and many people tried to avoid her.

Oddly enough, Joan and my mother became fast friends. The friendship satisfied my mother’s impulse to be kind to losers. For Joan it meant someone to talk to about her myriad interests, including ancient aliens, the continent of Atlantis and the writings of clairvoyant Edgar Cayce. She was somewhat well known for her own uncanny predictions, including the big Coos Bay earthquake back in 2002.

Joan came so close to having her life turn around that it’s heartbreaking. An eccentric millionaire named David Warner (he owned the adult movie theater where Pee-wee Herman was arrested) took an interest in her. He found her fascinating and totally original, so he said he would support her if she would write the story of her life.

An exhilarated Joan started her book in a novelistic style rather than as straight autobiography. She called herself “Twyla.” But with the bad luck that defined her life, she died after completing the first third.

I was one of the few lucky enough to read it. It begins with Twyla in bed with movie tycoon Darryl Zanuck. A few chapters later she meets Irving Berlin and begins an affair with him. But the biggest shock of the book is the way Joan portrays her mother. Helen Griffith comes across as a Joan Crawford-like monster, demeaning and abusing her daughter and constantly telling her she wishes she had never been born.

Would Joan’s book have been a success? It’s possible. Her exuberant descriptions of sex and show biz circa 1955 remind you a little of Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls. It could have found an appreciative audience. God knows it had the ring of truth.

It was while she was working on the book that I found out the truth about her daughter’s father. One boozy night at Turtle’s she told me who it was. I promised not to tell, and I’ll keep that promise. I owe it to Joan—and to the family of a certain deceased Hollywood movie star.

Sarasota Herald-Tribune headlines about the Nadel scandal.

Image: Courtesy Photos

Back in the early 2000s, Sarasota was seized by a mass psychosis. Everybody suddenly wanted to make money. Enormous sums of money. Greed was in the air.

The easiest way was real estate. At the time I owned a rundown vinyl-sided cottage on Irving Street and can remember looking out the window and being mystified at all the cars that kept creeping past. Why were they driving so slowly? Then it dawned on me— they were looking for property to buy. Any property.

Only idiots were staying out of the action. The only question facing a homeowner was, do I take $500,000 now? Or do I wait six months and take $700,000? I swear to God, no one thought it would end. It never occurred to us. Sarasota had become a fool’s paradise.

Enter Art Nadel. Art had been around forever. I knew him as a little guy who played the piano in jazz clubs, or would have if Sarasota had any jazz clubs. He was the ex-husband of my good friend Virginia Hoffman, a local artist and political gadfly. She rarely talked about him and had clearly put him in her past.

But around 2002 or so, you started hearing about him. He had gone into some sort of hedge fund business and married Peg Quisenberry. He had a new life and seemed to be getting somewhere. Had I misjudged him?

Apparently I had. He turned out to be a financial genius. Starting with an investment club back in 1997—that’s where he met Peg—Art had worked his way up to some sort of investment system involving computers. Back in those days everybody was doing this, but Art’s turned out to be pretty good. The word spread. After all, Sarasota is full of retired and semi-retired people with sizable nest eggs.

You needed $100,000 to buy in, which left me out. But 400 people did buy in, and the returns were astonishing. Nineteen percent one year, 21 percent the next.

I watched Art and Peg crash society. They gave to everything and they gave a lot. Catholic Charities. Girls Inc. The Sarasota Opera. They were Habitat for Humanity’s largest local donor.

But it didn’t feel right. You sensed something phony was going on. Was it the slightly comic way they looked together? She was tall, he was short. Was it their middle-class appearance, such a contrast to the sleek polish of most rich Sarasotans? Why did they continue to live over by Center Gate—the middle of white-bread Sarasota? Why did they drive a green Subaru instead of a black Mercedes?

Late one night in 2009 my phone rang. It was a reporter from New York who asked what I thought about Art Nadel’s disappearance. It was the first I’d heard of it, but I pretended to be the expert she thought I was. As soon as she got off the line I started making calls of my own.

It turned out Art had cheated his clients out of millions ($167 million by one count, $397 million by another) through a classic Ponzi scheme, then wrote a suicide note and fled to Louisiana, where he was apprehended 10 days later in a bar. During those 10 days Sarasota assessed the damage and learned the meaning of an ugly new word: “clawback.”

Of all Sarasota villains Art Nadel is the most opaque. Friends describe him as “brilliant” and “charming—sometimes,” but also as someone always looking for the big score. Even back in his piano-playing days he manipulated friends and relatives into poorly thought-out business deals, and then the money would somehow disappear.

Art pleaded guilty and died in prison in 2012, but the great mystery in the Nadel story is “What did Peg know?” Most feel she knew something. She worked with Art, she helped build the business. What about that note he wrote when he left, telling her to shred certain papers “the usual way?”

My own opinion—and I interviewed her so many times that she even came to my birthday party—is that she knew very little. She was a victim of that mass hallucination that gripped the town, a sort of Salem witch trial situation. We didn’t want to know the truth, that making money so quickly was impossible.

So we all plunged blindly ahead and over the cliff.

Well, this has been a little depressing. I’m afraid I’m portraying Sarasota as a town of grifters, con artists and liars. And it certainly has that side. I once asked John D. MacDonald where he got his material. “I read the Herald-Tribune every day,” he replied.

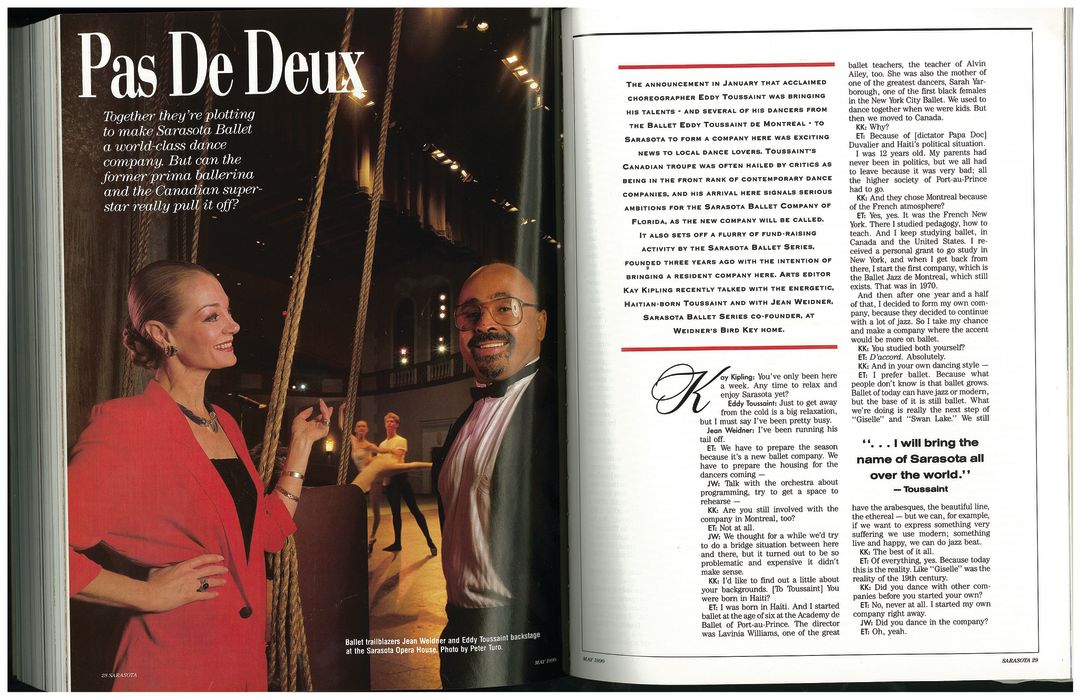

The ultimate odd couple, Jean Weidner and Eddy Toussaint, in a 1990 Sarasota Magazine story.

Image: Sarasota Magazine Archives

How about some heroes? Let’s see. I could choose Brother Geenen, who started the Senior Friendship Center, but the blameless life of a monk may not provide enough tantalizing gossip. There’s Howard Millman, who rescued the Asolo from bankruptcy. His life might provide too much. So I’ll choose the ultimate Odd Couple of the Sarasota arts scene, Jean Weidner and Eddy Toussaint.

As the 1980s progressed, the town became more sophisticated and worldly, not to mention richer. New people arrived from exotic places with new ideas. One of them was a glamorous former ballet star named Jean Weidner. Born in Zimbabwe of British parents, she attained fame as a prima ballerina for the Stuttgart Ballet in Germany. Now she was in Sarasota with her husband Ken, a wealthy retired businessman from Indiana, and she was looking to start a ballet company.

Jean’s plan was to present touring companies for five years while she explored the possibility of a resident company. But things shifted into high gear when she struck a deal with a Montreal choreographer named Eddy Toussaint. Suddenly they were in business, two years ahead of schedule, and faced with the impossible task of creating a world-class dance company in a little town in Florida.

Eddy Toussaint was an unlikely candidate for the task. Born and raised in Haiti, he had moved to Canada as a teenager when his well-to-do family left for political reasons. He was controversial in Montreal, where the critics either loved him or hated him. His style was eclectic—part ballet, part jazz, with occasional Caribbean/folkloric influences.

Those of us at Sarasota Magazine (we published the ballet’s program book) remember the atmosphere of barely contained crisis that permeated every aspect of the ballet’s early years. Finances were precarious and administrative skills were being learned as they went along. But the buck always stopped at Jean Weidner, and it took Eddy some time to realize this.

His reviews here echoed his Canadian ones. Some people loved his originality, but his dances were not to everyone’s taste, and his Nutcracker left some people puzzled, particularly the part in the second act where the cast goes to another planet.

But Eddy himself was an asset to the Sarasota social scene, with his French accent and sharp personal style. He was mystified by me at first, but when someone told him I could get the ballet lots of publicity we became fast friends. At parties he would run across the room to greet me. That is, until he found out I really couldn’t get him that much publicity and our friendship cooled somewhat.

Eddy and Jean parted ways after three drama-filled years. The position then went to Robert de Warren for the next 13 years. Then it went to Iain Webb, who currently holds it, with the spectacular addition of Joe Volpe, famed former general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, running the business side.

The real hero of the Sarasota Ballet is and always has been Jean Weidner (now Jean Weidner Goldstein), whose dream has paid off beyond anyone’s imagining. It’s enough to forgive the hell she put us through back in the early program book days. When I congratulated her not long ago on yet another rave review in The New York Times, she looked at me with a proud smile and said, one old-timer to another, “My, how our baby has grown.”

And so has Sarasota. It’s bigger and the stories are better than ever.

Just look at what’s going on now. The famous Gary Kompothecras family and their TV show (Siesta Key) that the town loves to hate. Joe Gruters and his rise from altar boy at St. Martha’s to poster boy for the Republican party. And what about Stephen King? He’s living out on Casey Key, writing one bestseller after another, and nobody seems to know anything about him. What’s the story?

I’m saving these for our 50th anniversary issue. And believe me, they will be worth the wait.