Tidewell Hospice Workers Help People Die Peacefully

Image: Everett Dennison

Aside from being rustled out of bed at 4:30 on this June morning, before even a crack of sunlight could part the darkness, Jane Johnston says today is one of her good days. The 95-year-old reclines against a couple of pillows stacked on a small bed on the third floor of the Summit, a downtown Venice assisted-living facility. Soft blond-gray hair frames her face and fresh lipstick brightens her lips. In front of Johnston sits “Pinky,” her nickname for her walker. To her left sits Jill Salak, a social worker with Tidewell Hospice, the only licensed and accredited hospice in Sarasota, Manatee, Charlotte and DeSoto counties. Salak’s fingers tap on a laptop keyboard while she chats with Johnston, a retired schoolteacher, about how she’s feeling. Bruises dot Johnston’s wrist and forearm, and her feet are swelling. Yesterday, while trying to get something from her closet, she fell.

It wasn’t her first tumble. Last November, while Johnston was still living alone, she fell while out walking. Doctors later found a broken pelvis, a blood clot, an ulcer and a compression fracture in her back, and she was in and out of the ER and rehab until February. In March, she moved in with her son and his wife; a CT scan in April revealed vascular disease. A physician estimated she had between two weeks and two months left to live and suggested that her family call Tidewell. To qualify for hospice services, which are typically covered by insurance, Medicare or Medicaid, a patient must be diagnosed as having six months or less to live. On May 16, she moved into the assisted living facility, where Tidewell staffers visit her throughout the week.

As Salak collects data, other Tidewell staffers pop in and out. Lisa Nick-Karuba, a certified nursing assistant who often takes Johnston outside for walks, stops in to say hello before visiting someone across the hall. Tiffany Muller, a registered nurse, asks whether Johnston might need Lasix, a diuretic, for her swollen feet.

After talking with Salak for a bit, Muller says her goodbyes. “Drop in anytime and see me, dead or alive,” Johnston says.

“I guess it’s going to be one or the other, right?” Muller jokes back.

Johnston laughs and sighs. “You have no choice,” she says.

Throughout history, humans mostly died at home. But with medical advances and the institutionalization of health care in the first half of the 20th century, Americans began living out their final days in institutional settings. By 1992, 57 percent of Americans were dying in hospitals, 17 percent in nursing homes and just 20 percent at home, according to research published by Northwestern University.

And yet, that’s not what most people wanted. Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, the Swiss-born psychiatrist whose 1969 book On Death & Dying helped popularize discussions about end-of-life care, testified before the U.S. Senate in 1972 that after interviewing 500 dying patients, she found that roughly four out of five would prefer to die at home if possible. “We live in a death-denying society,” she said, decrying the “loneliness of dying” and calling for greater support for grieving families and home caregivers.

The concept of hospice was becoming known in America at about the same time. The physician Cicely Saunders opened the first modern hospice in post-World War II London and imported the idea to the United States in the mid-’60s. America’s first hospice opened in Branford, Connecticut, in 1974. Tidewell was founded just six years later.

Today many Americans are trying to plan for a peaceful end. Florida has yet to join the five states that have approved physician-assisted suicide, but statistics demonstrate a growing interest in hospice care as a way to ensure one’s final months are as pain-free and peaceful as possible. Three new hospices have opened in Florida since 2009, bringing the total number of providers to 44; the number of patients in hospice care grew by 12 percent, from 107,294 to 120,155, between 2009 and 2015. Tidewell’s patient load grew from 7,827 in fiscal year 2009 to 8,424 in 2015.

And fewer deaths are occurring at hospitals. In 2000, more than half of American deaths (50.2 percent) still happened in hospitals. That number dropped to 37.3 percent by 2014. The number of American patients in hospice, meanwhile, has risen, from 25,000 in 1982 to 1.5 million in 2013. The number of providers has grown to almost 6,000.

Americans may be more comfortable with the idea of end-of-life hospice care, but that doesn’t mean the decision to accept it comes easily. Hospice workers still battle the impression that embracing hospice means giving up—surrendering to disease and death—or that it’s something you turn to only at the very end.

“I didn’t know anything about it,” says John Johnston, Jane’s son, who lives in Venice. “At the time we got Tidewell involved my mom could barely communicate. She’d be sitting in a chair and start falling over, and conversations were disjointed.” He believes the attention and affection of hospice have improved his mother’s well-being and extended her life beyond her original prognosis.

But still, not every day is a good one. “One day she’s fine and the next day it’s starting all over with the same questions,” John says. “‘Take me to a doctor to get me fixed.’” Johnston will sometimes implore him: “Get me out of here.”

Tidewell’s team has been an enormous help, says John. “They help guide you through this process,” he says. “You’re struggling to try and fix things and you have to come to the realization that you can’t fix them.”

"They want to gift back what we gifted them," says Michael Argulwicz, a hospice house clinical director.

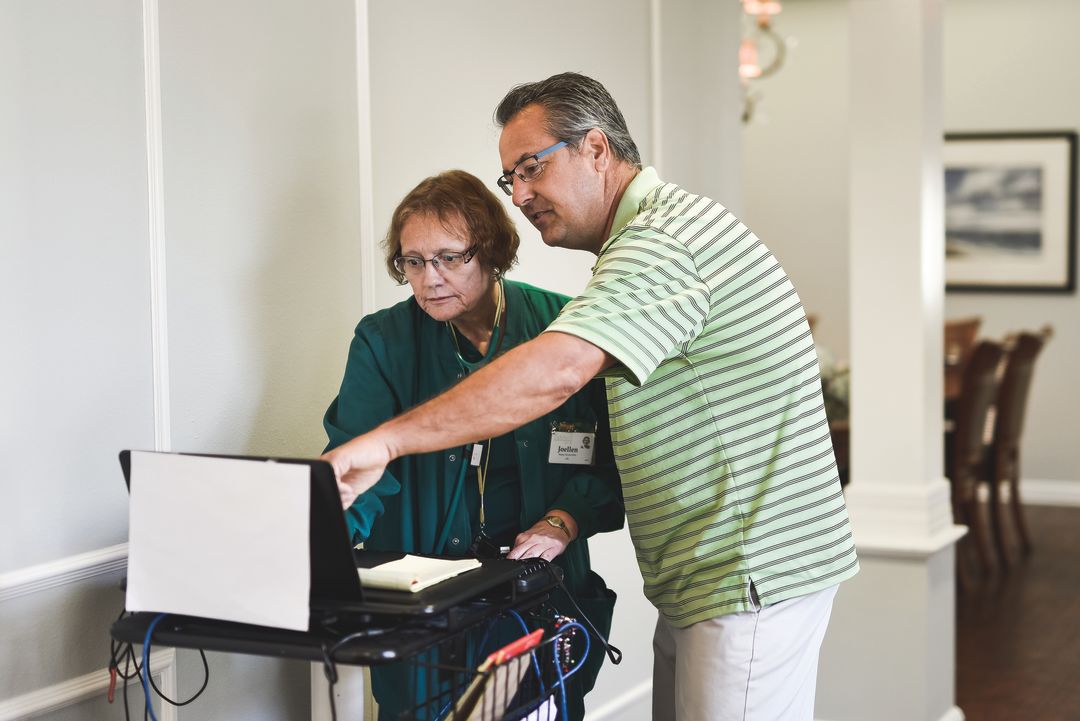

Image: Everett Dennison

There’s no single Tidewell experience. The nonprofit’s programs reach patients who live independently at home or at assisted-living facilities, and it also operates seven hospice houses in locations as far south as Port Charlotte, as far north as Ellenton and as far east as Arcadia.

Care teams typically include a social worker, a nurse case manager, a nursing assistant and a chaplain, who work in coordination with physicians, grief specialists and volunteers. Together, they monitor patients’ health, connect them with social services, communicate with family near and far and spend time with their charges—listening, playing music, reading out loud, doing whatever it takes to make them comfortable. They’ve even sneaked pets into the hospital to snuggle with their owners.

Patients enter hospice in every state imaginable. Some are “walkie-talkies”—mobile and communicative. Others are bed-bound. Some have chosen hospice; others rely on family members to make the decision. Many suffer from dementia. Some die within an hour of being admitted. Others “graduate,” meaning they outlast their six-month diagnosis (and coverage) and must leave. Some are as young as 4.

You might think the work would be dispiriting. You’d be wrong. For many Tidewell employees, hospice care isn’t a job. It’s a “calling” or a “vocation,” they say, something they will never stop doing.

“There’s always an epiphany,” says Denise Kassal, a 54-year-old certified hospice and palliative nursing assistant who has been with Tidewell for four years. Her epiphany occurred before she worked in hospice, while she was attending to a patient who was dying. Hospice couldn’t get there in time, but Kassal was able to get a representative on the phone to walk her through what to do. On another phone, she was talking to the patient’s family. “I was like, ‘Whoa, I got to be a part of this,’” she remembers. “She had a very peaceful death, and that’s when I knew: ‘All right, now I know why I’m here.’”

Soon after, Kassal applied for a hospice position in San Diego and earned additional certifications in hospice and pain care. She didn’t tell friends about her decision. “You know what everyone’s going to say: ‘How can you do that? It’s going to be so sad. That’s not good for you.’” They would never understand that it’s not really a choice, she says. “I know why I’m here,” Kassal says, “and I will always be a part of hospice.”

Kassal says “magic” happens during the dying process. Patients speak to long-gone friends, family members and pets. They relive war stories and sometimes rally, sitting up in bed and bursting with speech. “It’s like you’re birthing someone,” says Kassal, an analogy you hear often when talking to hospice workers.

Tidewell social worker Cindi Smith says that to be effective, hospice workers must be comfortbale with their own mortality.

Image: Everett Dennison

“Being present at a birth, that is what it’s like being present at a death,” says Cindi Smith, a 59-year-old Tidewell social worker. “It is the most sacred thing, just nothing like you’ve ever experienced, and you walk away from it going, ‘Wow. I just witnessed that.’ Stepping from this world to the next—it’s an amazing experience.”

Smith has been with Tidewell for nine years. Busy raising two kids and serving as a pastor’s wife for much of her life, she went back to school at age 42. She knew she wanted to do social work, because she’d already dedicated so much of her life to it. She grew up Mennonite in Sarasota and performed a year of service work after high school. She later spent three years volunteering with her husband in Jamaica and for years helped church members find support and counseling. “I thought, ‘Why don’t I get paid for this?’” she says.

During an undergraduate internship with a Kansas hospice program, something clicked. “People say, ‘How do you do that? How do you work with dying people all the time?’” says Smith. “Death has to be something you yourself are not afraid of to be most effective. My faith allows me to be at peace with my own mortality.”

Tidewell nurse Kim Barker.

Image: Everett Dennison

Humor helps hospice workers cope. “You’re killing me,” goes one common joke. Patients and their families need laughter, too. One patient at Sarasota Memorial Hospital decided to play a practical joke on his son, who didn’t know his father had signed up for hospice. Kim Barker, a Tidewell admissions nurse, was in the room when the son walked in. The patient held his breath and pretended he was dead. “The son screamed and fell to his knees and said, ‘Oh, no, I’m too late. I didn’t know,’” Barker remembers. That’s when the patient opened his eyes. “Can you rub my feet?” he asked his son, shaking with laughter.

“Everybody handles it differently,” Barker says.

In truth, death is a small part of what Tidewell employees concern themselves with. Many patients are poor. As a social worker with 35 to 40 patients at any given time, Smith has helped residents get their power turned back on and sign up for Medicaid and food stamps. She’s tapped into one Tidewell donor’s “wish” fund to fly in relatives who couldn’t afford the trip or to buy CDs and clothing for patients or to send people on trips to Disney. No two patients’ situations or experiences are alike. Workers talk with patients to understand what will bring them joy in the dwindling number of days they have left.

“Most people, when they come to the end of their life, they want to know, ‘Have I been effective in my life? Have I meant anything to anyone or anything?’” Smith says. Part of her job is helping people overcome regrets and feel forgiven in their final days. “When you don’t have that,” she says, “there’s more turmoil and agitation, restlessness.”

Families who see the transformative effects of hospice care sometimes volunteer with Tidewell after their loved ones die.

If there’s one thing that frustrates hospice workers, it’s when patients arrive too far gone. “We still are finding difficulty in educating the public,” says Kassal. “The saddest part of my job is when we get the patients too late. Doctors are not willing to let go yet. Doctors are still in the mindset of ‘I can fix them.’”

That leads to stressed and panicked patients and families. “We could have had them for six months and held them through the process and prepared all of them,” says Kassal.

The average stay with Tidewell is 54 days. “It’s such a darn shame, because you’re entitled to at least six months, and it can make such a difference,” Barker says.

But attitudes are changing. Consider the analogy between dying and birthing. The percentage of midwife-assisted births in America has risen almost every year since 1989. Expectant mothers are taking control of the birthing process by giving birth at home or in birthing centers, rather than in hospitals, decisions that aren’t so different from the terminally ill choosing to die in a hospice setting instead of a hospital.

“People are making their own decisions now,” says Barker. “They know you don’t have to listen to the doctor, you don’t have to do what they say. When you’re done, you’re done.”

Peg Crouse signed up for hospice after deciding she was tired of stressful trips to the emergency room.

Image: Everett Dennison

Hospice wasn’t a new concept for Peg Crouse, 97, who has lived at the Windsor, a Lakewood Ranch assisted-living facility, for nine years. Her sister recently died in hospice care in Pennsylvania, and her daughter, Marsha Tyrrell, who lives in Parrish, has several friends with relatives who entered hospice. Crouse has a mass on her lungs that makes her voice hoarse. She’s been in and out of the hospital six times in the last year. For her, contacting Tidewell wasn’t a difficult decision. She decided she’d rather remain comfortable in her apartment than go through the stress of the hospital again. Here, she can participate in the Windsor’s arts activities and day trips and read the poetry she loves in peace and quiet. Tidewell workers bring kindness, caring and humor.

“It gave me great relief to know that I have these people I can call on at any time if we have an emergency or see something that doesn’t look right,” says her daughter.

Crouse grew up as a Pennsylvania farm girl who loved playing music and performing in shows. She later filled the home she made with her surgeon husband with music. Her daughters toured as part of a singing group; her son performs as an operatic tenor. She founded a choir at the Windsor after moving in. Many Tidewell patients can’t communicate, but Crouse remains vibrant and talkative. She insists on serving Arnold Palmers to her guests and offering them chips when they leave. She chooses her clothes with care—today she’s wearing a smart turquoise jacket with a matching scarf colored with a swirl of pastels—and is quick to crack a joke. Crouse has a saying about death: “This is one trip we all have to take.”

We all die someday. Our heartbeat slows. Our hunger and thirst dissipate. Our breath turns into a rattle. Our eyes grow fixed. We separate from the world around us. We perish. Hospice offers hope that we can do so at peace.