Six Sarasota Tourist Attractions From the Past

Sarasota has always had a special relationship with its tourist attractions. First of all, we all make money from them in one way or another, and second, for the residents they become “civic amenities,” places we visit regularly, for fun, enlightenment or maybe just a drink with an umbrella in it.

Some have been here forever—the Ringling, Selby Gardens, spring training. Some are brand new—the Sarasota Art Museum of Ringling College. And some have gone to tourist attraction heaven, living only in our memories as we think back and marvel, “Did such a place actually exist?”

Let’s take a look at six long-gone favorites and try to discover what they say about our town and its history.

Image: Ringling Museum Archives

Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Winter Quarters

The Winter Quarters was the Disney World of its day, a place people all over the world had heard of and dreamed of visiting. For years it was the biggest tourist attraction in the state. When I moved here in 1985, people still showed up looking for it.

It wasn’t designed as a tourist attraction. It was a workplace, a village, really (at its height, 1,600 people worked there), where the Ringling Brothers rested between tours and rehearsed new acts. It was enormous: 160 acres, located between Beneva Road (then called Oriente) and the Bobby Jones Golf Course.

Image: Ringling Museum Archives

Strolling down its dusty streets, you could see the various circus departments toiling away (paint, seating, rigging, electrical). There were dormitories for hundreds of workers, and a railroad yard with hundreds of cars. In two large circular “ring barns,” equestrian acts rehearsed and aerialists honed their skills while you could sit and watch. There was food at the commissary, and two hospitals, one for people and a slightly larger one for animals.

These were the real attraction. The circus traveled with an enormous menagerie. You could see 50 elephants, a large collection of monkeys and apes at “Monkey Island” and all sorts of exotic species in the pens and stables: gnus, yaks, zebras and antelopes. The giraffe colony had a special one-and-a-half story stable, and there was even a complete aviary.

Visitors were advised to stick around for afternoon feeding time, when each elephant was served a meal of 125 pounds of hay, 15 to 25 pounds of bran, oats and salt, all washed down with 60 gallons of water. Sometimes they would let the kids help with the feeding.

In 1956, the circus abandoned its tents and began performing in arenas. The Winter Quarters became much less important. Several years later it was sold to the Arvida Corporation along with other remaining Ringling properties. The Glen Oaks subdivision was built on the site, and today nothing remains of the Quarters but a historic marker—and one of Sarasota’s most persistent urban legends. When homeowners in Glen Oaks put in a swimming pool, it is said, they often find elephant bones. The great beasts were buried here when they passed away, lowered into the earth via a crane.

By the way, if you want to get a feeling for what the Winter Quarters was like, take a look at the amazing 4,000-square-foot model at the Ringling Circus Museum. You'll see over 42,000 pieces, including 1,500 people, 500 animals and 55 railroad cars. It's become quite a present-day tourist attraction itself.

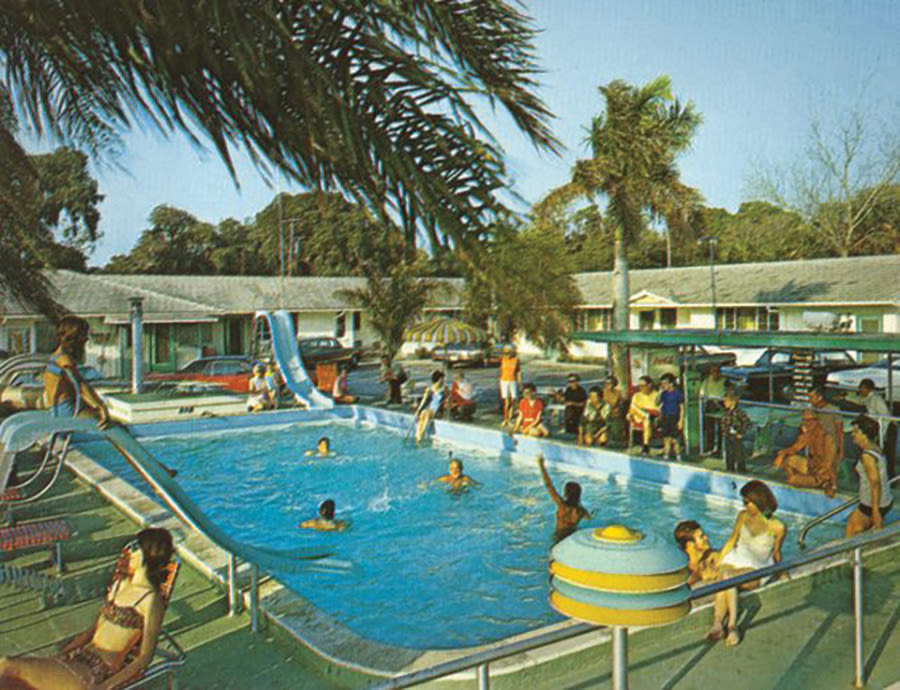

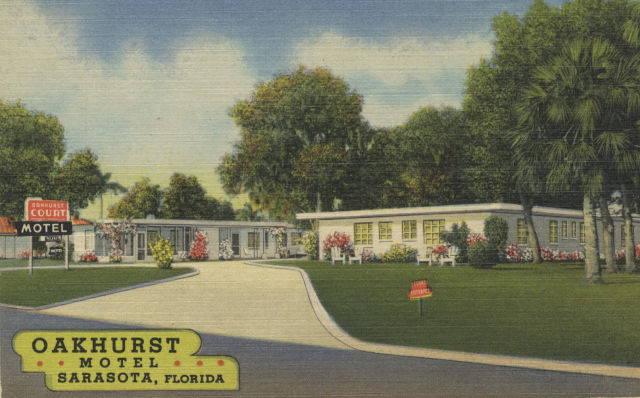

The North Trail in Sarasota was lined with 1950s motels that offered enticing kitchenettes, TVs and swimming pools.

Image: FloridaMemory.com

Mom-and-Pop Motels

When tourism exploded in the 1950s, all those tourists had to stay somewhere, hence all the motels. In 1960, Sarasota had an astonishing 244 motels. We were a tourist town, no doubt about it.

These were the classic motels of the 1950s, when the motel eclipsed every other form of lodging—the hotel, the tourist home—to become an important part of American life and culture. They were wholesome and clean, but also a little racy. (For an astute and hilarious look at the subject, take a look at Nabokov’s classic novel Lolita, much of which takes place in 1950s motels.)

Sarasota’s most notable motel district ran up and down the North Trail. They were the first thing you saw as you drove into town. They sort of waved at you, beckoning and enticing would-be customers with neon signs and promising kitchenettes, TVs and swimming pools—things rarer and thus more appreciated back in those days.

Let’s see….there was the Americana, the Mt. Vernon, Burke’s, the Lee-Etta, the Floridora, the Sunnyside, the Rainbow, the Cadillac (still there), the Flamingo Colony (also still there), the Town House, Hilltop Courts, the Twin (still there), the Monterrey Village (maybe still there; it’s hard to tell), the Pioneer with its “pulse-pedic” mattresses where you put in a quarter and it vibrated. And that’s just a five-block stretch.

Motel owning was a socially acceptable profession back then. (The founder of this magazine came from a motel family.) It was a particularly appealing business for retired people, and that included retired circus performers who wanted an investment that would allow them to make some money off their fame. There was a couple who were enormously tall circus freaks who owned a place. And then there was Unus.

Unus Southland Motel

Unus, born Franz Furtner, was an Austrian acrobat who had perfected one amazing trick. Clad in white tie and tails, he would stand on his forefinger. There was a little cheating involved, as there was a steel brace hidden under his sleeve and glove, but it was riveting to watch. He performed before Hitler. After World War II, Unus was brought to the United States by John Ringling North, and he was a Ringling headliner for years.

His motel was called the Southland, and just to make sure people knew it was his, he placed a neon sign out front of him in tails, standing on his forefinger.

One of my first assignments in Sarasota was interviewing Unus. He was living on a mini-estate in Desoto Acres, with his name soldered onto the gate and a Cadillac in the driveway. (The garage was being used to store his press clippings.) He was very Teutonic and rigid, with little sense of humor, and became very defensive when I brought up anything to do with World War II.

I’m not sure when Unus sold his motel, but during the 1970s visitors began to switch to the beach. Then I-75 was built. The motels went into decline, and by the 1980s the North Trail had come to resemble the red-light district of Amsterdam. Hookers paced the street and drug deals were conducted in the parking lots.

Things are much better today. New landscaping, public art and even a Starbucks. It seems that every other year a plan is announced to do something wonderful with the old motels—the latest is to turn them into artists’ studios—but nothing ever happens. It’s a shame. They were a wonderful collection of odd, midcentury buildings that for many years were synonymous with a Sarasota vacation. As for Unus’ motel, it’s now the parking lot for a new tourist attraction, the Marietta Museum of Art and Whimsy, with its flying pigs and giant flamingos.

The Buccaneer

The Buccaneer’s pirate theme included a bar that looked like a sunken ship and a live parrot.

Image: FloridaMemory.com

Every vacation needs a special evening out, a trip to a “fun” restaurant unlike anything back home, a place with great food and an atmosphere that everybody, even the kids, finds exciting. For Sarasota, that restaurant was the Buccaneer.

Located on the then-still-exotic Longboat Key, the Buccaneer started life as the Sleepy Lagoon Club, a dive bar purchased in the mid-1950s by Herb Field, a key figure in Longboat Key history. He started the Colony (then sold it to Murf Klauber) and also built another legend, the Far Horizons resort. But the Buccaneer was the cherry on top of his numerous endeavors.

You knew things were going to be special as soon as your car door was opened by a pirate with a peg leg. He was called Long John Silver, but his real name was Ransom Webster, a one-legged vagrant who was seen trudging down U.S. 301 with his 9-year-old daughter. Herb heard about him and offered him a job. He had him fitted for a wooden leg, put him in a pirate costume (designed by Max Weldy of Ringling Brothers) and a local legend was born.

Inside, the restaurant was nautical. It was not a fancy-French kind of place; the tables were laminated wood and there was a sunken bar that was supposed to suggest a wrecked pirate ship, where you could listen to live music. You could arrive by boat, and many people did. What a perfect day circa 1965. Lunch at the Buccaneer and a sail around the bay.

As good as the atmosphere was, the food was even better. There were a lot of shrimp and fish dishes and an oyster bar, but the specialty was the chargrilled roast beef. They took a thick slice of rare roast beef, threw it on the grill, and seared it on both sides. Prices on the menu were listed in the Buccaneer’s own currency, with a handy conversion chart. Doubloons were $2; pieces of eight were 25 cents.

Image: FloridaMemory.com

Children adored the Buccaneer. If you ordered a baked potato, a serving wench would appear with a platter of fixin’s. Each meal was completed with make-your-own sundaes, and another platter of sauces, syrups, sprinkles and such would appear. And then, on your way out, you got to reach in the treasure chest by the entrance and pick out a toy to take home.

The Buccaneer closed in 1992, but it has become such a legend over the years that Casey Gonzmart, owner of the Columbia, is planning to build a new Buccaneer. It was his favorite restaurant as a kid (after the Columbia, he hastens to add) and the new one (to be constructed where Pattigeorge’s used to be on Longboat) will honor the spirit of the original. He’s already collecting antiques and memorabilia for the décor. All over town elderly Sarasotans are rejoicing at the news.

Image: FloridaMemory.com

Floridaland

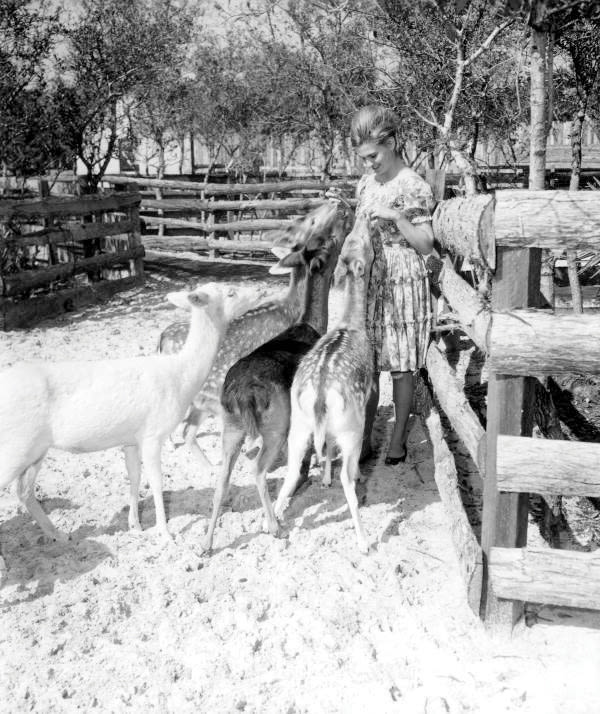

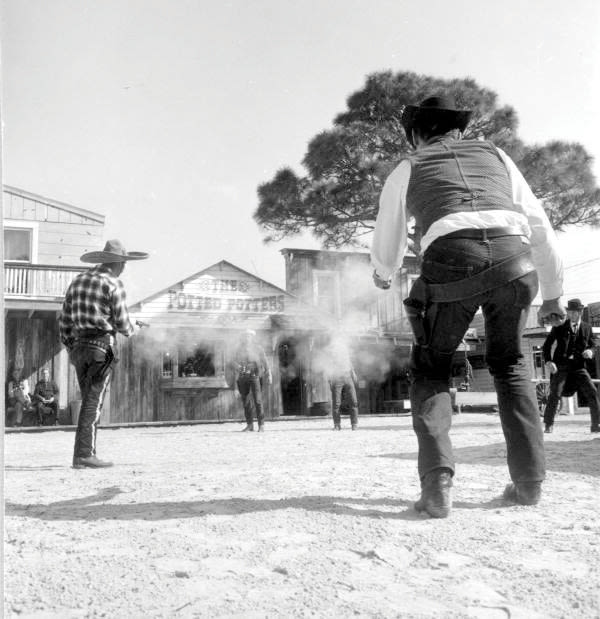

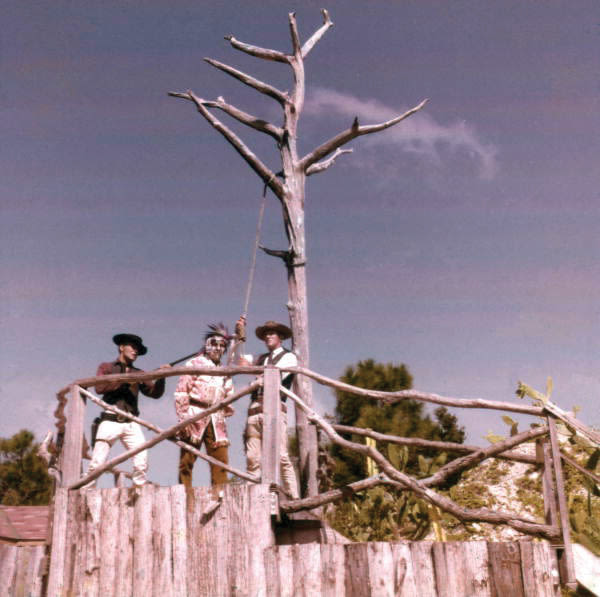

A petting zoo and cowboy shootouts were highlights at Floridaland.

Image: FloridaMemory.com

Not all of Sarasota’s tourist attractions were successful. Some were dangerous, or in poor taste. Some suffered from bad timing. Floridaland suffered from all three.

The gimmick was you got 10 typical roadside attractions for one price: $2.50 for adults, half price for kids. These were the tacky attractions that you saw all over Florida back in those days (the 1960s), all gathered together down in Osprey. There was a Western town complete with saloon and cancan girls, a hill with billy goats climbing about, a porpoise show, a deer park, a tropical bird show, a cactus garden, live alligators, a tunnel of love and so on. In the deer park, animals performed and chickens played baseball.

Reading about what went on in Floridaland can be unsettling by today’s standards.

Image: FloridaMemory.com

The porpoise attraction had, as part of its show, a segment where children were towed around the pool in a little dinghy without any sort of flotation device. And over at the Western town there were shootouts in the street, with cowboys shooting each other to death (some tumbled off the roof) while the crowd looked on, their ears ringing from the sound of gunfire. It was like a mass shooting right in your midst. I have also seen reference to public hangings, but dismissed them as ridiculous until our art director found the photograph at right.

Floridaland had a few good years. It even managed to get its own Holiday Inn. But it was not really a success, and when Disney World opened in 1971 it was immediately obsolete. Today it’s part of Southbay Yacht & Racquet Club, a quiet neighborhood popular with boaters. Of the billy goat mountain and the petting zoo there isn’t a trace, just what lives on in the memories of the Sarasotans who still gleefully recall the broken legs and ankles they acquired while working at Floridaland in their carefree youth.

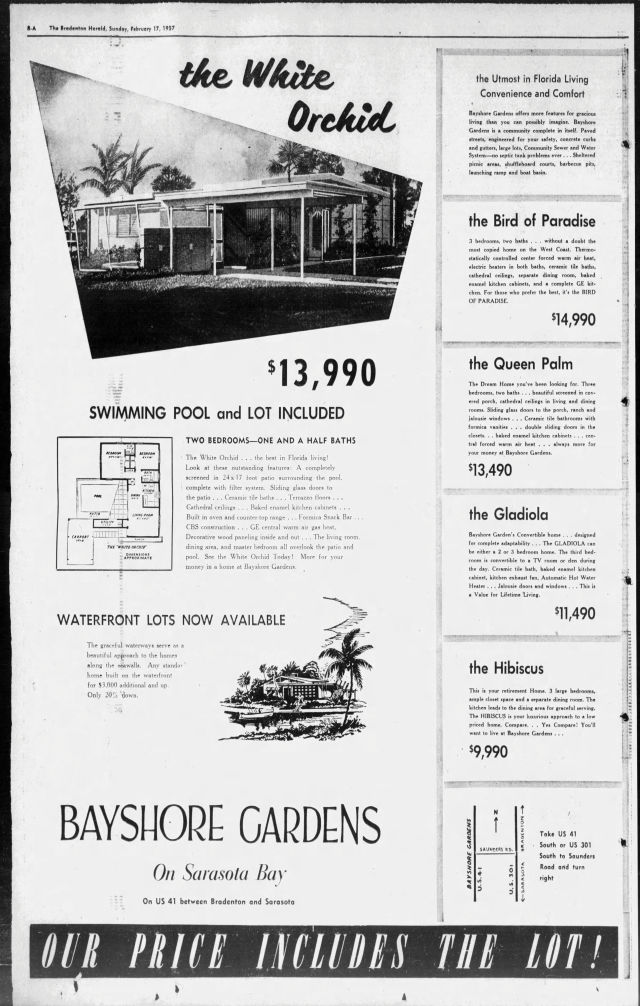

One of Bayshore Gardens’ typical midcentury homes.

Bayshore Gardens

One of the strange effects Sarasota has on tourists is that it makes you want to live here. You picture yourself going to the beach and golfing every day and the daydreaming starts.

A whole business has sprung up to make money off that daydream. It’s called real estate, and it provides the tourist with a great sightseeing attraction: Florida model homes. Back in the ’50s you had plenty of choices, particularly in subdivisions like Paver Park and Kensington Park. But the one you really had to see was Bayshore Gardens. It was more than just houses for sale. It was a complete community.

Bayshore Gardens' community pool

Image: Manatee Couny Public Library

Bayshore Gardens was (and still is) located just northwest of the airport, on 3,200 acres of land that had been used to grow tomatoes. Opened in 1956, it had everything, and if it didn’t have it, it was planned. There was a school, a marina, a 40-acre shopping center with its own Publix, churches, medical facilities, an enormous recreation building, a baseball diamond, a movie theater and even a junior college.

Visitors toured model homes, like the White Orchid

You would tour the seven model homes. There was the Seagrape, the Gladiola, and the crowd favorite, the very midcentury-modern Bird of Paradise—three bedrooms, two baths, a GE kitchen, described in the advertising as “fabulous beyond belief.” Prices: $8,000 to $15,000.

Bayshore Gardens offered free trips for potential buyers and cash prizes if you could get friends to buy in. They gave away turkeys at Christmas. The ads worked, and the place became an enormous success, attracting a very wide demographic, from young families who wanted all the recreational activities to retirees who could sit by the six miles of waterfront and join the bridge, bowling or shuffleboard clubs. It was the largest voting precinct in the area, and local politicians knew they had to get “the Bayshore Gardens vote.”

Bayshore Gardens isn’t what it used to be. It declined over the years, and the most trouble I ever got into writing for Sarasota Magazine was an article mocking today’s Bayshore Gardens for its general shabbiness and ramshackle remodeling jobs. The whole population turned on me. So I will just describe today’s Bayshore Gardens as a pleasant place, very conveniently located, full of nice if rather small older homes. I’ve found it odd that it has never really caught on as a place for hip people who want a nice little midcentury house to restore. But it still could.

Its real power lies in what it started. Today real estate tourists visit Lakewood Ranch and ooh and aah over the model homes while poor Bayshore Gardens looks eastward with a sneer, like Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard: “Lakewood Ranch? Hmph. Without me there wouldn’t be any Lakewood Ranch.”

A postcard shows the beach pavilion’s concrete seahorses

Image: FloridaMemory.com

Lido Casino

Lido Casino was the most beloved building in Sarasota history. Not only was it a tourist attraction we could be proud of, it was also the town square. Everybody would show up for all sorts of reasons: swim lessons, beauty pageants, sports tournaments, birthday parties, charity events, cocktails at sunset, dinner, dancing. It was a lot more than just a day at the beach.

A beauty pageant at the Lido Casino pool

Image: FloridaMemory.com

Built with WPA money in 1940, it was the sort of beach pavilion they have in Europe—upscale facilities and a place to see and be seen. It was designed by Ralph Twitchell, the town’s premier architect, in an art deco style, with lots of strong horizontals and its signature concrete sea horses, a motif you still see all over town.

There was a wading pool for little kids, a big pool with high and low diving boards (Sarasota High held swim practice there every morning at 5:45) and a snack bar, locker rooms, etc. But it also had a cocktail lounge, a fancy dining room in white and cherry red whose walls folded back to reveal the Gulf, and a full-size ballroom with a famous big band (Rudy Bundy and his orchestra) playing for dancing couples. During the war there was a shuttle bus from downtown so all the soldiers from the airfield could join in the fun. Excluded, though, were African Americans in heavily segregated Sarasota.

Still, the town has loving memories of the casino. Historian Jeff LaHurd wrote a book about it. Writer Charlie Huisking recalls it was his childhood castle, where he learned to swim and would peek into the ballroom and watch his parents dance. Maybe he also saw LuAnn Palmer, who as a teenager performed her contortionist act as part of the entertainment. Years later, LuAnn would be performing a different contortionist act as Sarasota’s mayor.

Band leader Rudy Bundy at the Lido Casino

But tastes changed. Fancy hotels were built nearby, and the Art Deco style of the casino became dated. Public funds were voted for its restoration, but something happened—nobody is quite sure what—and the casino was demolished in 1969, suddenly and without much explanation. The swimming pool was saved and a snack bar added, but nothing was left to suggest the scale or importance of the place.

That is, until 2018, when Hurricane Michael uncovered its ruins. Large slabs and chunks of concrete appeared, much to everyone’s amazement. It was thought that all the rubble had been carted away decades ago, but here it was, tons of it, and solid as a rock. Even today, if you poke around in the seagrass you will see pieces. Most eye-catching was the single slab of red and green tiled floor, still as vivid as it was back in 1940. For an instant the casino comes back to life, with everybody all dressed up and listening to Rudy Bundy and his band as they play “Amapola” in the tropical moonlight.