Sarasota’s Black Cemeteries Have, Thankfully, Been Preserved

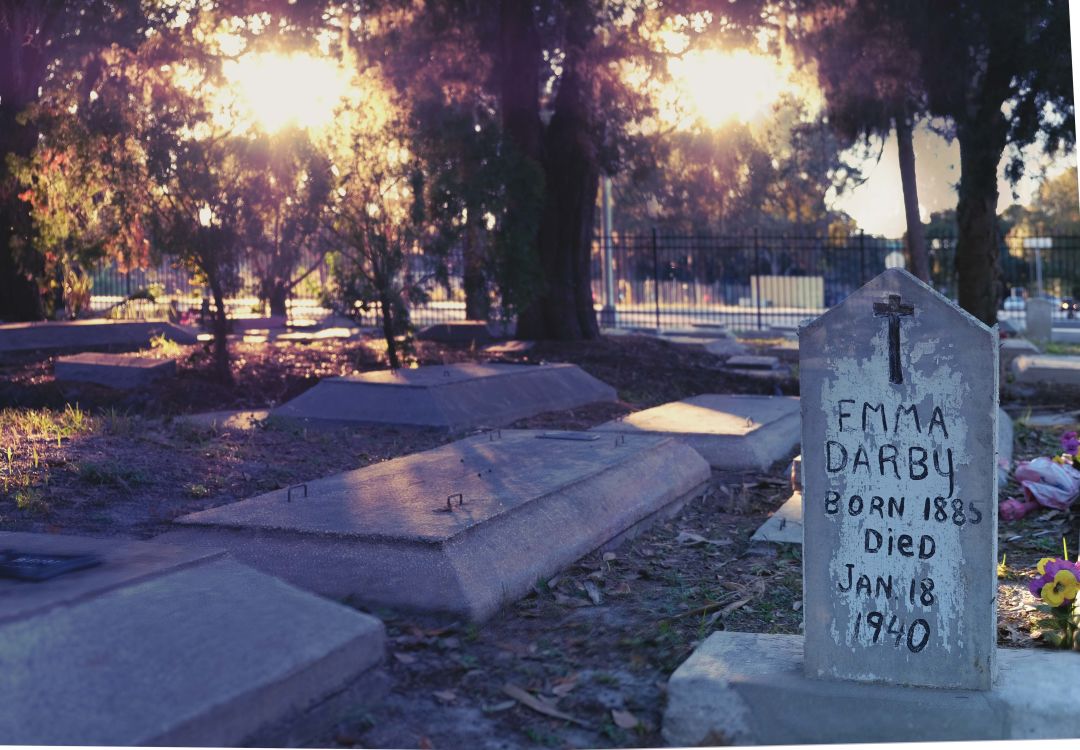

Galilee Cemetery in Newtown.

Image: Isaac Eger

I do not believe in ghosts. Still, I removed my hat and watched my step just in case any of the dead were watching the first time I visited Galilee Cemetery, one of Sarasota’s two Black cemeteries.

Galilee is off noisy U.S. 301 and Myrtle Street, tucked between a waste management facility and an industrial equipment rental company in Newtown, Sarasota’s historic Black community. Built in 1932, during the Jim Crow era, Galilee was Sarasota’s second Black cemetery. The first, Oaklands/Woodlawn Cemetery, was built in 1905. No sign announces Galilee and the history it holds, but more than 1,500 bodies rest there. Headstones mark birthdays as far back as the 1880s and as recently as last year. Some graves hold people who lived generously long lives and shoebox-sized tombs hold the very young. The graves of veterans stand out with their marble headstones. Flowers, both real and plastic, ceramic cats, framed and faded photos, and a glass jar filled with marbles adorn the tops of graves.

The history of segregation and Black cemeteries in Florida and around the country was highlighted in 2019 when two Black cemeteries in Tampa were discovered. For nearly a century, the graves of Zion Cemetery lay buried and forgotten under warehouses and a housing complex until a cemetery researcher tipped off a Tampa Bay Times reporter. Archaeologists used ground-penetrating radar to discover nearly 200 graves. The discovery led to other tips of lost and forgotten Black cemeteries. The next was Ridgewood Cemetery, perhaps Tampa’s first Black cemetery, where 145 bodies were found beneath a high school campus. Both cemeteries were knowingly built upon by city officials. Since then, another seven buried Black cemeteries have been found, and experts expect more to be uncovered. For many people, these lost Black cemeteries have become a metaphor for how the U.S. has dealt with its history of racism. We simply buried it and built on top of it.

Fortunately, Sarasota’s Black cemeteries have been preserved. Maintaining any cemetery isn’t easy. As fewer people choose caskets and graves, the elderly have become the caretakers, and they often struggle with managing the costs. Sarasota’s Black cemeteries had a board of trustees—where positions were often passed down to other family members—but it was failing to collect enough money to operate the sites. Twenty years ago, a few Newtown residents formed the volunteer Galilee and Woodlawn Cemeteries Restoration Task Force to rid the graveyards of decades of weeds and trash. They made some improvements, but the cemeteries were still in disrepair. Then 10 years ago, the City of Sarasota asked Uzi Baram, a professor of anthropology and archaeological historian at New College of Florida, who had documented Sarasota’s historic white burial ground, Rosemary Cemetery, to document Galilee.

Collaborating with the task force, Baram and New College and State College of Florida students surveyed Galilee, photographing all 1,544 graves and writing down the names and birth and death dates of each person buried there and plotting the data on an organized grid. In 2016 and 2018, spurred by former Sarasota City Commissioner Willie Shaw, the city used ground-penetrating radar to survey Woodlawn and Galilee for a more complete picture, and is funding the upkeep of both cemeteries as well as Rosemary Cemetery.

Cemeteries are a history of people and physical places that hold a society’s memories, Baram says, and Galilee is unique among Sarasota’s cemeteries because it still has a community of people connected to those buried there.

“The relatives of the people buried in other cemeteries, like Rosemary Cemetery, don’t live here anymore,” Baram says. “Most of the descendants of Galilee still live in Newtown.”

Shaw is one of them. “It’s our story,” he says. “My ancestors are buried there. Our families are buried there.”

As I walked out, two cars pulled into the cemetery’s only road. The doors opened and a family, three generations deep, all neatly dressed, carried bouquets of flowers to one of the graves.