Our Snooty, Ourselves

I probably shouldn’t admit this, but in July, when Snooty, the South Florida Museum’s 69-year-old manatee, got trapped in a plumbing area of his tank and drowned, I was sorry—but not upset. So I was taken aback by the mounting frenzy of Princess Diana-style grief. Mourners laid flowers on the museum grounds, newspapers around the world ran tributes, social media shared and sobbed, and maybe most surprising of all, several of the hardened journalists in this office sat around all morning looking gloomy and swapping Snooty stories.

I didn’t get it.

Pam Daniel

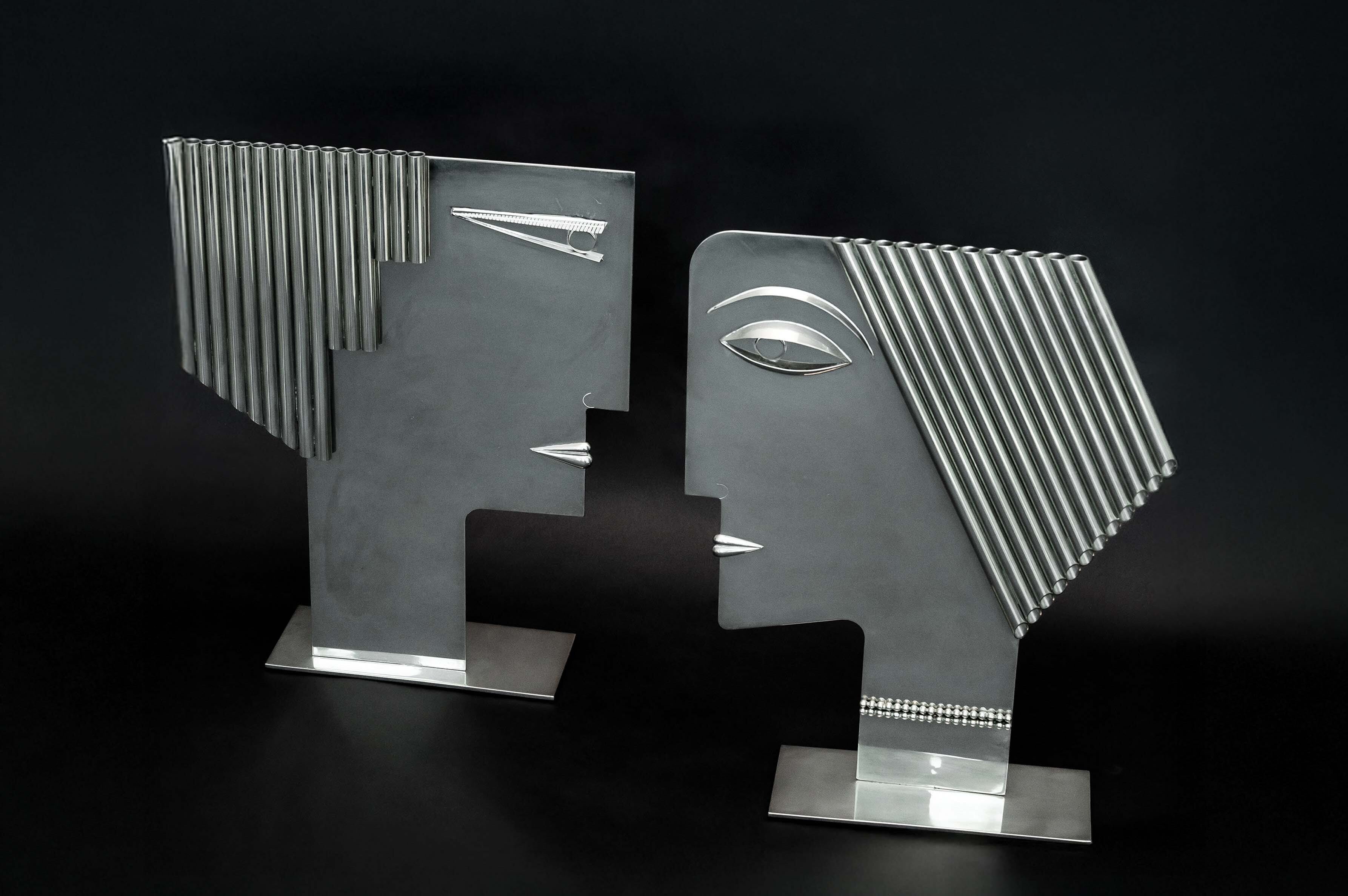

Image: Rebecca Baxter

It’s not that I don’t care about manatees—I do. I love sitting on our dock at night and hearing the soft, ghostly swoosh of their breathing as they surface and sink. And I’ll never forget the morning one lifted its big, gray, whiskery face out of the water, just inches away, and we stared at each other for a long, thrilling moment of interspecies communion.

But I believe manatees are better off in the wild, away from human interference. I didn’t hit “Like” when a friend recently rhapsodized on Facebook about swimming with—and embracing—manatees in the Gulf, and the idea of keeping one confined in a tank for his entire life depressed me.

Besides, some of the reaction to his death seemed to verge on hysteria—like members of one animal rights group, who demanded the firing of the entire museum staff and board, North Korean-style, so the protesters could begin to “heal.”

But my feelings about Snooty’s life started to change as I read the story Craig Pittman wrote for our September issue. Pittman, a reporter for the Tampa Bay Times, is famous for his investigative environmental journalism, but his “Remembering Snooty” is simple and straightforward, tracing the life of the gentle, lumbering creature from birth to death. And it turns out that from the very beginning, that life was entwined with humans. Indeed, if it weren’t for the people who rescued his mother after she was hit by a boat, Snooty would never have been born, and he seemed to revel in his caretakers’ hugs and attention. At the museum, he would rise out of his tank and look at visitors, sometimes even nuzzling them or touching them with a flipper. Occasionally he’d show off some of the tricks he’d learned, rolling over or twirling in the water.

Does all that mean that Snooty loved people? I’m not sure. It’s easy to attribute our own emotions to animals—especially soulful-looking marine mammals of obvious intelligence. But that legions of humans loved—adored—Snooty, there is no doubt. On the South Florida Museum website, people have posted pages of tributes to Snooty. Many say they visited him year after year; some tourists included a pilgrimage to his tank in every vacation. A few describe him as a “magical” soul mate who recognized them and glowed with happiness on his birthday celebrations. One woman says that when her mother got sick, she turned to Snooty “to help to endure it.” And person after person wrote about visiting Snooty first as a child, then as a parent and grandparent.

For all sorts of reasons, Snooty came to represent more than a captive in a zoo. With his squishy, shapeless body and benign gaze, he was the epitome of adorable, a joyous Disney cartoon of a creature who evoked Disney-like feelings in those who stood before him. He was pure, happy, wise and good. “Boy, could he love,” one writer declared. And he was the living embodiment of Bradenton’s past, a reminder of the days when everyone in town knew each other and everyone knew Snooty—and when it was OK to cage wild animals and let schoolkids feed them lettuce. Though the world changed, Snooty never did. Most of all, I’ve come to understand, he embodied innocence. Without him, for an astonishing number of people, the world is a darker, lonelier place. As one woman wrote, when Snooty died, “my childhood died.”