Dr. Bernard Watson Played Pivotal Role in Battle Over Priceless Art Collection

To understand how Bernard C. Watson, distinguished educator, civic leader, civil-rights champion and Sarasota resident, triumphed in a dispute over one of the world’s greatest troves of post-impressionist art—a dispute settled years ago, but that still throbs like a wound in the hearts of some Philadelphians—it’s helpful to recount the incident that has informed much of his life.

It was 1949, and there was something about the car that made Watson, then a young college student, uneasy, as it slowly trailed him on his walk toward his fraternity house. “About a block before I got to my house,” he recalls, “a guy got out of the passenger side and put a gun right under my nose. He said: ‘We know who you are, nigger, and I want you to know that I could blow your fucking brains out and nobody would know or care.’ Then he got back in his car, and it drove off. He was dressed as a cop, but it wasn’t a cop car.”

That incident occurred at the Indiana University, where Watson had become known as a tenacious voice for racial equality. Almost seven decades later, it still seethes in his memory, a pivotal moment in a remarkable life.

As he tells it in his 1997 memoir, Colored, Negro, Black; Chasing the American Dream, he had never been so scared, but afterward, “I was never afraid of dying again. I knew from that day forward how quickly, how quietly, how easily and unexpectedly death could come to anyone, but especially to those who rocked the boat. It was then that I began to form my own philosophy about standing up for things you believe in. Be prepared to stand alone; don’t expect support or assistance. Be prepared to accept the consequences.”

Those convictions would nourish him during a shifting career as a teacher, school administrator, university professor, foundation head and, ultimately, a key actor in the ugly drama that led to the relocation of the dazzling art collection of Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation, an episode that stamped him as a hero or a demon, depending on one’s perspective.

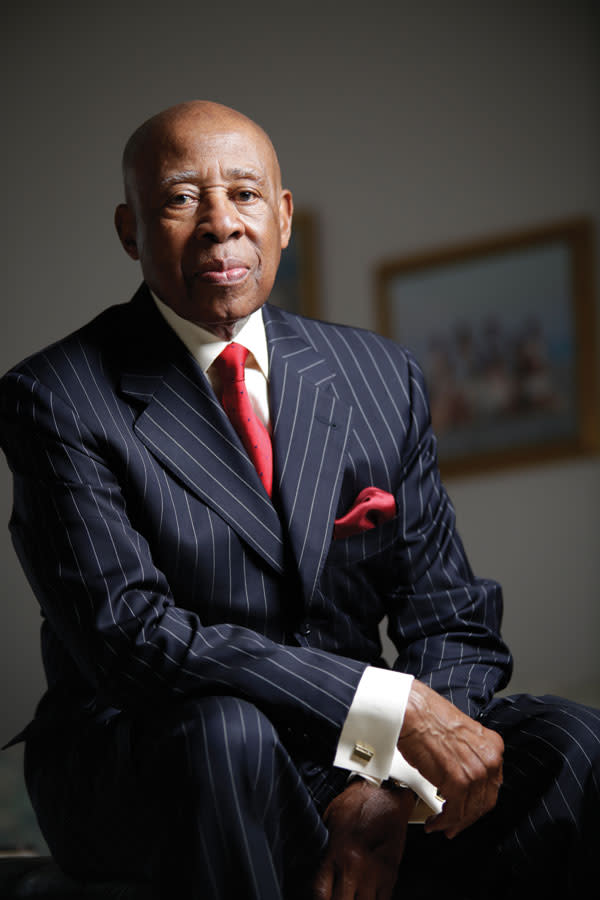

Sitting in the office of his University Park home, Watson certainly doesn’t look like someone who would inspire such passions. Wearing a maroon shirt, yellow shorts and white athletic shoes, he’s polite, articulate, humorous, welcoming. A compact individual, he looks grandfatherly—he does, in fact, have four grandchildren—and 10 years younger than his age, 87, testimony to a disciplined diet, regular exercise and fortunate genes.

“Serious,” “guarded,” “private” are among the words some longtime acquaintances use to describe him. The impression a visitor gets: This is a man who knows how to transform life’s realities, regardless of how grim, into positive resolve. Smart, perceptive and, as his critics say, shrewd, he’s also someone against whom it probably wouldn’t be much fun to play poker.

***

Bernard Charles Watson was born in 1928 in Gary, Ind.—not the sad, diminished Gary of today, which, with about 80,000 residents, has lost more than half its population since the nation’s steel industry began a slow decline in the 1960s—but a vibrant Gary, in an America bursting with industrial power. It was a true company town, taking its name from that of an executive of U.S. Steel, which had founded it in 1906, not far from Chicago’s railheads and Lake Michigan’s iron-ore carriers, on land purchased for $800 an acre.

In 1921, Watson’s parents, originally from Alabama, had migrated from Ohio, after they heard that the steel giant was hiring people, including African-Americans, and paying them well. “My father applied for a job in the morning and went to work that afternoon,” Watson says. “He stayed there until he died.” His father, Homer, a World War I veteran, had little education. His mother, Fannie, was a rarity among black women of that era: She had a college degree. Says their son: “How she and my father got together, I have no idea. But they were devoted to each other, raised five children, educated them. It wasn’t at all that unusual in Gary at the time.”

What also wasn’t unusual in Gary—or anywhere else in the United States outside the South, where overt Jim Crow reigned—was de facto segregation. Watson recalls his father as “one of the smartest people I ever met,” a man who easily learned to run a complex and crucial piece of equipment at the steel works, but who couldn’t win advancement because of his color. A tribute to his abilities: He wasn’t laid off during the Depression.

Ironically, the oppressive racial climate had one benefit for Gary’s black students in the 1930s, 1940s, and early 1950s. Most went to Theodore Roosevelt High School, which had been built specifically for “the colored.” Its principal, H. Theodore Tatum, recruited talented black teachers from all over the country. Today, these men and women might work in academia or business, research or industry. Back then, teaching positions, especially at a school like Roosevelt, were among the only good jobs they could land. As a result, the faculty outshone those of many white high schools.

“The teachers didn’t take any crap. They made you work,” Watson observes, “and they told us: ‘You have the ability to do anything, but don’t expect to have the same opportunities as the white kids. So you’ve got to be better.’” Life at Roosevelt could be fun, too. Watson, who plays saxophone and clarinet, joined the school band, honing a love of jazz, and cheered the sports teams, which sometimes vied against white opponents, often successfully.

In 1944, with World War II under way and many workers in the military, he turned 16—the minimum age to qualify for a job at the steel complex. He worked there on weekends, after school, and on summer vacations, to earn money for college.

After Roosevelt, Watson earned a bachelor’s degree at the Indiana University, where he majored in education, political science and history. Next, he joined the Air Force, entering as an enlisted man during the Korean War and exiting as a first lieutenant. Then he earned a master’s degree in education from the University of Illinois. In 1955, he returned to Roosevelt as a social-studies teacher and guidance counselor, before being named its assistant principal, as well as principal of the junior high housed in the same building.

Randall Morgan, a Sarasota orthopedic surgeon who is the grandson of H. Theodore Tatum and attended Roosevelt, says that Watson was very popular with students. He tried hard to understand their personalities, problems, and talents, and had innovative ideas. “He always wants the best schools, the best people, the best communities. At the high school, he had some of the most famous figures in black history visit us: Joe Louis, Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, Marcus Garvey, Louie Armstrong,” Morgan remembers. The goal: to expose students to worthy role models.

Watson’s work in Gary later figured in his becoming the first black to be named outstanding young administrator by the American Association of School Administrators. It also led him to his wife, Lois, a teacher and librarian, now a board member of Sarasota’s Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe. Their union has lasted over a half-century. (Roosevelt High’s best days, however, are long gone. Today, it’s run by a for-profit education company, after having been taken over by the State of Indiana for ineffectiveness.)

***

In 1965, Watson left Gary for good, to attend the University of Chicago, where he earned a Ph.D. in social sciences in 1967. He had become a hot academic commodity and had plenty of job offers. The position he accepted was in Philadelphia, where school superintendent Mark Shedd and school board chairman Richardson Dilworth were trying to revitalize and desegregate a fractured education system. By the time he left three years later, Watson had become deputy superintendent and had learned lessons himself, in big-city politics.

It was the tumultuous era of the Vietnam War and an escalating civil rights movement, and one incident stands out in his mind. On Nov. 17, 1967, 3,500 black students congregated at the school administration building, voicing demands that included the hiring of more African-American teachers and principals. Watson was one of two school representatives dispatched to negotiate with the group’s leaders. The talks were progressing peacefully, he says, until Frank Rizzo, the police commissioner, decided to take control.

Rizzo, the self-styled “toughest cop in America” who once boasted that he’d “make Attila the Hun look like a faggot,” ordered his officers to disperse the crowd. As Watson describes it, police, “black and white alike, descended on those students, beat the hell out of them and drove them into center city, rather than back to their own neighborhoods. Some stayed on the streets, some were thrown into jail.” But then, Dilworth, a white patrician who’d been the city’s district attorney and mayor, disarmed the situation by sending school buses to take demonstrators back to their neighborhoods. “That made Dilworth the police force’s public enemy No. 1,” Watson says, and ensured that Shedd, Dilworth’s choice as school superintendent, would be gone, as he was soon after Rizzo was elected mayor in 1971.

By then, Watson had left, too, for a full professorship in education at Temple University, where he founded the Department of Urban Education and later became the university’s academic vice president.

Does Watson see parallels in the 1967 incident to today, when shootings of blacks in Ferguson, Mo., Baltimore, and elsewhere have shone a spotlight on often fractious, sometimes fatal, confrontations between police and people of color? Sure, he says. “Maybe it’s a surprise to you [whites], but not to us. It’s just become more visible because everyone these days has a cellphone with a camera.” In fact, despite horrors like the recent murders of nine members of an African-American church in Charleston, he maintains that America’s racial divide is much smaller than it once was: “In Sarasota, I can live wherever I want to live, if I can afford it. American Express has a black CEO [Kenneth Chenault]. And there’s a black man in the White House. Sixty years ago, none of that would have been possible.”

***

In 1981, Watson left Temple to become CEO of the William Penn Foundation, a philanthropic organization. Over the next quarter-century, he would become an integral part of Philadelphia’s civic fabric, serving on more than a dozen municipal, corporate and cultural boards and commissions.

One was that of the Barnes Foundation, created in 1923 by Albert Coombs Barnes. Born in 1872, Barnes came from a working-class family, but, clever and driven, had become a physician at age 20. Later, he and a German chemist developed Argyrol, an antiseptic that prevented newborn infants from getting gonorrheal eye infections. It made both rich, and Barnes eventually bought out his partner. He got richer still when, with miraculous timing, he sold the business in 1929 for $6 million—$83 million in 2015 dollars—months before the Wall Street crash.

Barnes’ passion was collecting art. Paying as little as $300 for paintings now considered priceless, he assembled what many view as the world’s greatest collection of post-impressionist and early modern works—his 69 Cezannes alone outnumber those in all of Paris’s museums. The Barnes Foundation’s 3,000 pieces include 59 Matisses, 46 Picassos, 181 Renoirs, as well as works by Modigliani, Seurat, Van Gogh, Degas and African, Asian and Native American art.

But when Barnes exhibited some of his art in Philadelphia in 1923, the critics savaged it, much as French critics had ridiculed the impressionists at their initial 1874 exhibition in Paris. Infuriated, he pronounced the city “a depressing intellectual slum,” and built a home for his collection in suburban Lower Merion. His intent was to create an educational institution, with the art as its centerpiece. Students could learn about art there, and regular folk would be welcome, but viewing hours were strictly limited. Above all, he wanted to keep his collection out of the hands of the art establishment, which he identified closely with the Philadelphia Museum of Art and its donors, whom he despised.

To that end and to tweak the elite, Barnes, in an indenture to his will, gave Lincoln University, a black college, the right to appoint four of the five members of the board that would oversee the collection after he died. The indenture specified that the art always must be laid out in the manner Barnes favored—packed closely together, with sometimes disparate, sometimes complementary, works adjoining one another, with prosaic objects, such as a doorknob, punctuating the display—and that it couldn’t be loaned, moved or sold.

Jump ahead to the year 1999—almost a half-century after Albert Barnes’ death—and the Barnes Foundation is in financial trouble. Barnes had left a $10 million endowment to the foundation, but it had been exhausted, and the institution’s finances had deteriorated badly, owing to mismanagement, costly and misguided legal battles, and tattered relations with the philanthropic community. Bankruptcy might not have been imminent, but it loomed.

In September of that year, Bernard Watson was placed on the board by Lincoln University; in December, he was elected chairman. “When I went there, we had some money, but in a special fund that could only be used for maintenance and capital things. The money from that went to upgrade the heating and air-conditioning system, the security system, and things like that. It was around $5 million; we had no actual endowment,” he recalls.

After studying the foundation’s problems, Watson chose a radical course: expanding the board to 15 members—most nonprofits have at least that many, to facilitate fund raising and bolster governance—and moving the art to Philadelphia, making it more accessible to the public. Lincoln University opposed the board expansion, which would end its control of the Barnes. And many groups, including lots of Lincoln and Barnes Foundation students, opposed moving the institution, deeming this immoral, illegal and a violation of Albert Barnes’ intentions.

Three powerful Philadelphia-area nonprofits pledged to raise $150 million to help bankroll the move: the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Lenfest Foundation, and the Annenberg Foundation—precisely the type of establishment bulwarks that Albert C. Barnes had hated. In fact, he had feuded for years with media tycoon Walter Annenberg, whose widow, Leonore, supported Watson’s plan.

The battle began on Sept. 24, 2002, when the Barnes board filed a court petition seeking to have its plan approved. Lincoln, feeling that the board, whose majority it had nominated, was stabbing it in the back, fought back. Over the next 2½ years, the two sides exchanged legal briefs and angry words. The proponents had one nuclear weapon in their arsenal: a provision in the indenture that, if the Barnes were no longer financially viable, the art collection could be turned over to another museum, which would have left Lincoln with nothing. The opponents, quite logically, argued that if the foundations could come up with $150 million to move the Barnes, they surely could provide the same amount to save and endow it in Lower Merion.

As the battle dragged on, Lincoln employed a powerful weapon of its own, accusing the board of racism, even though four of its five members were black. Says Jacqueline F. Allen, a Philadelphia judge and Lincoln graduate who was one of the four: “The suggestion that our position was racist was just otherworldly.” In truth, she stresses, the board was simply fulfilling its fiduciary duty. Throughout the dispute, Allen adds, Watson was a rock of resolve and a sea of calm. “I don’t know how we would have accomplished what we did without his leadership,” she says.

Opponents of the move have opinions about Watson, too, perhaps best summed up in an email from Robert Zaller, a Drexel University professor: “….The move represents the biggest theft of art since World War II. I believe this will define Dr. Watson’s legacy.” Some also contend that Watson was a puppet of the foundations, which were bent on simply making the Barnes a Philadelphia tourist attraction—a cultural Disneyland along Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

The legal war finally ended in April 2005, when Pennsylvania’s highest court upheld lower court rulings that had gone in the board’s favor. Along the way, Lincoln had obtained promises of financial aid from Pennsylvania Gov. Edward Rendell, a former Philadelphia mayor who supported the relocation. This would let it solve some financial problems of its own. And it got the right to nominate five of the new board’s members.

When the new Barnes Foundation building, which retained Albert Barnes’ idiosyncratic placement of artworks, was opened on May 17, 2012, The New York Times ran an appraisal atop its front page, with the headline: “A Museum, Reborn, Remains True to Its Old Self, Only Better.” The foundation’s financial underpinnings look better, too, with a board heavy on experienced fund raisers, such as Neil Rudenstine, Harvard’s former president; Tory Burch, the fashion designer; and Aileen Roberts, wife of Comcast’s CEO.

As for Watson, who retired from the Barnes Foundation last December, he’s enjoying life in Sarasota, which he’s found “warm and welcoming, surprisingly so—most of the places we’ve been haven’t been like that—maybe because it includes people from everywhere, not just people born in Florida.” He knows that he’ll never be forgiven by some in Philadelphia, but he’s unconcerned. “We went from bankruptcy to a solid financial state. That $150 million building’s paid for, and, at last count, we had nearly a $60 million endowment, headed toward $100 million,” he says. “We did what we had to do, and it was the right thing, no matter what anybody says.”

In the end, however, the real victor is the Barnes Foundation’s magnificent art itself, which, if mankind survives, will be admired centuries from now, long after the battle over where it should have been displayed is forgotten.

Contributing editor Rich Rescigno is a former editor at Barron’s. His “The (Multi-) Millionaire Next Door” in our March 2014 issue won a first-place Charlie award for in-depth reporting from the Florida Magazine Association, and he’s a finalist for best feature story and best investigative reporting in the Society of Professional Journalist’s 2015 Sunshine State Awards.