A Conversation With Poet Diana Khoi Nguyen

Diana Khoi Nguyen

Image: Courtesy Photo

Diana Khoi Nguyen grapples with ghosts in her poetry, which is shape-shifting in form—simultaneously cerebral, emotional and relentless. In addition to being a poet, Nguyen is also a teacher of creative writing and a self-taught visual artist who honors the past while pushing the bounds of creativity and unpacking her heritage as a daughter of the Vietnamese diaspora. In 2018, Nguyen published her first collection of poems, Ghost Of, which was a finalist for that year's National Book Award. Along with novelist Margaret Wilkerson Sexton, a fellow National Book Award nominee, Nguyen will be visiting Sarasota for a discussion called "Ghosts of Our Past" at Selby Public Library on Saturday, Aug. 17.

Sarasota Magazine recently spoke with Nguyen about her debut and the heartbeat of her writing.

Can you tell us a bit about how you started writing poetry?

I’ve been writing since at least third grade, but it was something I did more for fun. I have an undergraduate degree in creative writing, which is where I encountered journals and other poets. I used to read this journal in L.A. called Pool Poetry. I’m also a swimmer, so I loved all their various artwork around pools, and around the time I was graduating I submitted some work and they accepted it, which gave me the supportive energy to move forward. But it wasn’t until I was working in tech that I decided to pursue writing more seriously. I worked in Silicon Valley after my undergrad. I worked for Apple when Steve Jobs was still alive and I was pretty good at what I did, but I also wasn’t fulfilled. I took an extension course at Berkeley with a poetry workshop and I remember thinking, "This feels so good." But I didn’t consider myself a writer, and I wasn’t yet prepared to make a living this way. So I went to Columbia from 2009 to 2012 for my MFA and that’s when I really began writing in earnest.

When did you find your voice as a writer?

My undergrad mentor was pretty experimental, avant-garde in his aesthetic, and then in my MFA program my mentor was kind of the opposite—much more mythical and lyrical. And I thought of those two as my literary parents, so when I decided to pursue writing more seriously, sometimes I would think that something would make my literary mom and dad happy. But part of me realized I wasn’t writing for myself. I thought, "What does my own unique voice say, independent of how I had been fostered in educational institutions?" and so it took years to try to figure that out. And it was around that time that my brother committed suicide in 2014, and I ended a relationship I had been in for six years. I entered into a Ph.D. program, stopped working full-time in New York City and really began to dedicate my life to writing. So that’s the logistics of what was going on in my life when my writing itself changed—just something about the urgency of thinking about my brother and the trauma of his death, but also revisiting my family life.

How did you start working on Ghost Of?

Grief was an unpredictable, tricky thing I found myself in as I was trying to understand and make sense of my brother’s passing. He was 24 at the time and, two years prior, he went around the family house in the middle of the night and took down every family portrait in the house and cut himself out with an X-Acto knife, and then put all the pictures back up. And my family didn’t talk about it. We didn’t address it. Nobody took the pictures down. After my brother committed suicide, the pictures continued to hang in the house and we still didn’t talk about them. And it was really frightening to go home and walk around the house and see those pictures. So after my brother died, I really wanted to look squarely at those images and my complicity in that silence within my family, and how toxic that silence was, and I started to work with those images.

As I wrote poems, I started to revisit that problematic area, which opened up the door to explore my own complicated family history. I also had to look back and think about my parents and their own difficult, traumatic childhoods. They were both born in Vietnam in wartime, and at very crucial moments in their early teens, they had to flee their home country as refugees and come to America. And then they met here, they got married, they had kids and they never talked about the past. So there are so many ghosts there and the book was born from exploring various kinds of silences and spaces, as well as kind of charting my own progress as a daughter, sister and adult woman within the Vietnamese diaspora.

What was it like to share this work you had put your personal pain and experiences into?

I wasn't intending to share this with anybody. It was something that I felt that I had to do for myself because my family wasn’t talking about the suicide or acknowledging mental health as a valid thing. I did the work mostly to have conversations that I wanted in real life, but was instead having on the page to myself, to my brother, for my parents, etc. And once I had accumulated a lot of work, I remember thinking that this was a cohesive project that I wish had existed in the world for me to read right after my brother died. I also wondered if this would be useful or helpful for others who were going through similar situations in grief or family silence. And that was when I decided I wanted to put it out there in the world. I thought it would take years for the book to be published, but it got picked up right away. And what I began to witness were strangers coming up to me who connected with my work and my process in dealing with complicated grief, and that was really meaningful for me.

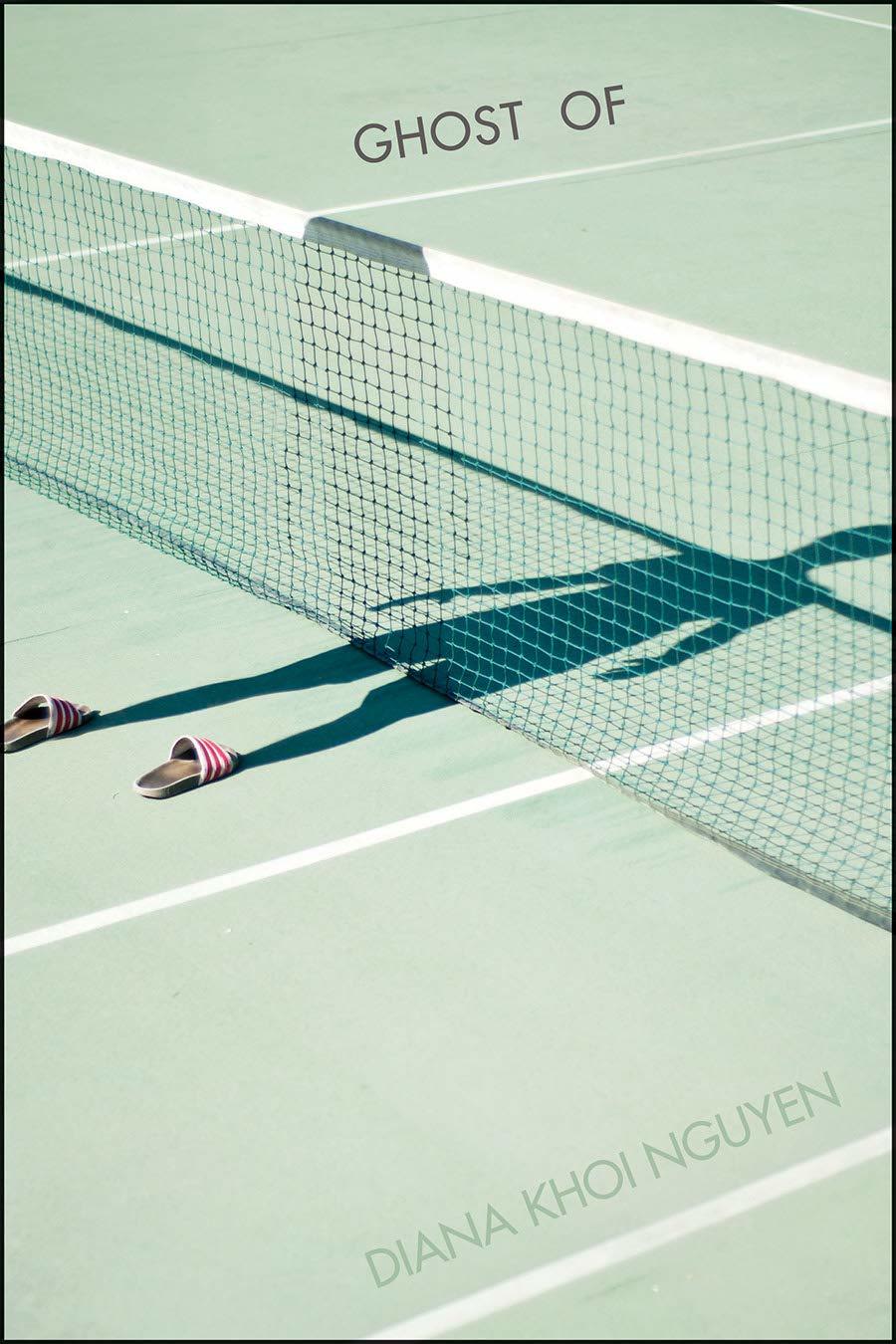

The cover of Diana Khoi Nguyen's Ghost Of

Image: Courtesy Photo

What do you want people to get from your work?

I want people to have permission to feel the full spectrum of their feelings. For example, there are some pieces in the book where I say things that I don't think I could ever say in person, which are like transcripts of me talking to my brother. I say, “I'm glad that you are dead,” and there's a relief in my brother's death because he was not well for 10 years. And I didn't have to go through my life waiting for this call anymore. Death is complicated, and I want others to feel safe in feeling these complicated feelings. It's not just, “I miss that person.” There are also all the other things, like that person was abusive, or complicated or haunting us while alive. And I want people to feel that they have community in those less polite feelings. Because grief is also a non-polite process, and I didn't feel like I had access to that kind of writing when I was going through my grief.

What can you tell us about your writing process?

I'm on an academic schedule and when I'm teaching I dedicate myself fully to my students. So I don't write during the academic year. I only write in the summer and in December for 15-day intervals each. I call them my marathon weeks, where I hardly even see people and the goal is to write something publishable each day. So it’s heavy on production—not just practice production, but something as polished as possible where the stakes are really high. That kind of pressurized system works for me and helps me to crystallize and condense. In December of 2015, the one-year anniversary of my brother's death, I started to do my "Triptych" poems. And I was also listening to a lot of Max Richter on repeat. There was something about being in that mood, and being aware and dreading approaching that traumatic day of the phone call where I learned that my brother died as I was looking at the artifacts that he had left behind. So I wrote in those conditions. It was almost like a dam had burst, and I had access to these feelings that had been under the surface before.

What inspires the lyrical, experimental aspect of a lot of your poetry and why did you choose this style?

In lyric mode, the emphasis is on musicality and sound. There are other modes, like narrative, where the poem tells a story. I wouldn’t say my work necessarily tells a story, but it does tell of different experiences and trajectories. But there's also heavy emphasis on sound and image. I think a lot about the world in a visual way and I'm also really attuned to what I hear. When somebody has died, there is no more sound. So I thought a lot about sound in writing my book and sort of talking to my brother in hopes of him hearing me, really just talking for myself to hear it out loud.

Bees also feature in my book a lot and contribute to the emphasis on noise. A crucial point came when my mom called me and she said, "Diana, Oliver died because we didn't listen to him." She said, "Well, you know, you know how he was an insomniac. Well, years ago he told us he could hear a humming in the wall, and we tried to look but didn't see anything. So we told him, 'Don't worry about it. Just go to sleep.' But your father and I, we were just cleaning in the attic and we found thousands of dead bees." My mother thought that the bees were keeping him up at night and no one else could hear them, and that he killed himself so he could finally sleep. And I was devastated hearing that because I understand the guilt that was implied in her sharing the story with me, but also that she thought that she had figured it out. Thinking about the sound of the bees and about my brother feeling alone in what he heard influenced my use of sound.

Beyond your family influences, what other themes inspired the poetry of Ghost Of?

I was also thinking about the larger failure in the ecosystem, along with the failure of communication that was happening within my specific family. In the very first poem of the book, it says there's no ecologically safe way to mourn. I wanted that line to be the first line for the book because I was thinking about ecology. It's not sustainable to bury anybody. It's also not good to the environment to burn everybody, but we have funeral rights because they are healing for us as a culture. We are born, we live, we suffer, we have joy sometimes and then we die. And that's kind of part of the fabric. And eventually we become part of the atmosphere or become part of the earth. We become part of everything. I read somewhere that we all have a little bit of star dust in us. All the matter that exists in the universe coalesces. But then we also return to the universe. There was kind of a nice comfort with just getting into the physics of that, but also in asking what it meant for the feelings that I feel, trying to understand the ecology of my emotional grief and its messiness.

What advice do you have for people who are serious about creating?

Give yourself permission to explore in any way you want to explore. For a long time, I didn't do this because I didn't go to school for it, so I didn’t feel allowed to. I wish for everyone to find ways to experiment and engage with what calls to them, but safely, because sometimes the themes that I've explored have been really hard on me emotionally. And that means having a support system of people who can encourage and be there for you. As a writer of color, I have not always felt that I had community in the various institutions that I had been studying in, and I had to actively build my own community in order to do the work that I've been doing. Nobody told me that I needed to do that, but I found myself needing that.

The National Book Foundation is presenting “Ghosts of Our Past,” a conversation and book signing at Selby Public Library, 1331 First St., Sarasota, with Nguyen and novelist Margaret Wilkerson Sexton, who was named to the 2017 National Book Award longlist, from 2 to 3 p.m. on Saturday, Aug. 17. You can reserve a spot at the event here.