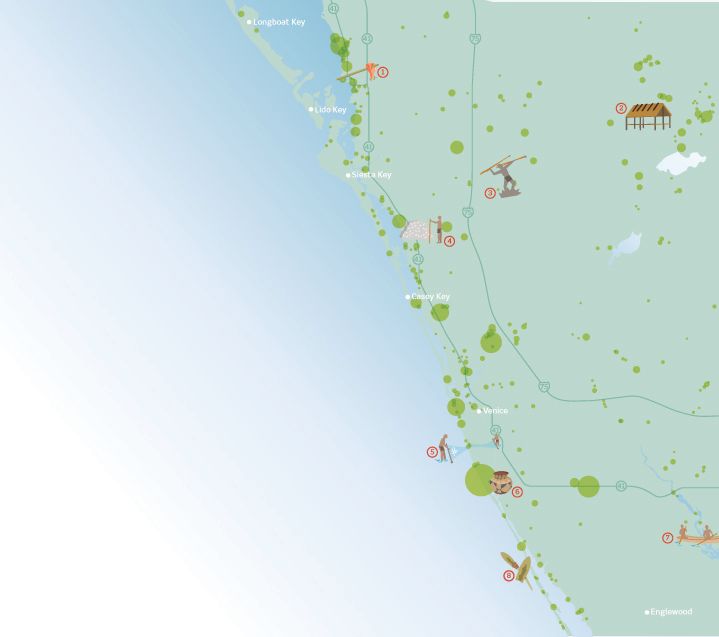

Manasota Offshore is a Treasure Worth Protecting

Manasota Key Beach.

Image: Shutterstock

Two summers ago, Joshua Frank was diving for fossils in 20 feet of water off Manasota Beach when he came across a discolored, barnacle-encrusted bone. He had found hundreds of fossilized shark teeth and bones in that area, but never a natural bone.

A team of underwater archaeologists soon determined that Frank’s find was part of a human jawbone that came from a 7,000-year-old burial site. The site has global archaeological significance because it proves that people lived on the inundated coastal plains of Florida during the last ice age, when ocean levels were much lower. That means many other sites lie under the waves, too.

After the discovery was announced earlier this year, press coverage quickly reached 500 million internet viewers. John McCarthy, the executive director of Historic Spanish Point, is reveling in the interest. He loves to talk about the Manasota Offshore site, although he will never lead a tour there. It’s unlikely that anyone ever will. And, he adds, the site is also significant because of how it is being managed.

Image: Staff

The Gulf Coast Community Foundation asked McCarthy to convene more than a dozen different groups who met secretly for 18 months to develop a plan. Representatives from state and county governments, the Seminole Tribe, three different police forces, artists and designers, homeowners’ associations, and other groups all got together, and they all kept quiet. “It’s very rare to see so many groups cooperating so freely on something like this,” says McCarthy.

The secrecy was necessary because the site is so important and so vulnerable. It was possible only because Frank did the right thing by contacting an archaeologist. Often, things don’t go that well. Steve Koski, Sarasota County’s staff archaeologist, gets a pained expression on his face when he talks about all the burial mounds that were carted off for road fill until the state stopped the practice in the 1950s. And then there’s Nona’s Site, one of several important burial sites in North Port. The General Development Corporation dredged a ditch though it in the early 1960s, casually tossing human remains onto the spoil pile.

People thought nothing of doing stuff like that back then. Now it’s considered a bad idea for several reasons. First, disturbing a cemetery is just plain wrong. Second, state and local laws passed in the 1980s and 1990s make it a felony to disturb any human remains in Florida, no matter how old they are. Also, there’s stratigraphy. An archaeological dig is like putting together a three-dimensional puzzle that has missing pieces. It’s nearly impossible if you mess up the original order.

Incredibly, burial sites in Florida are still being damaged and destroyed. A contractor who uncovers a bone or a piece of pottery on private land is likely to either overlook it, ignore it or keep it in a private collection because time is money, and archaeology takes time. The city of North Port redredged the canal through Nona’s Site in 2015, tossing more human bones onto the scrub, even though they had been warned not to (see “North Port May Finally Be Taking Steps to Limit Damage to Prehistoric Sites”).

Sarasota County has 319 archaeological sites listed in Florida’s Master Site File, and 66 of them have a high likelihood of containing human remains. That is just a fraction of what is out there, because people have lived on Florida’s Gulf Coast continuously for more than 12,000 years. The density of sites, combined with development pressure, creates a complicated relationship between local archaeologists, developers, native tribes and fossil collectors.

The plan for Manasota Offshore is significant because all parties were consulted before the digging began. At one end are the Seminole and Miccosukee nations, which insist that a minimum of bones should be disturbed and that all bones should be returned to the site. At the other end are hobbyists who just want to add cool stuff to their collections. Archaeologists are in the middle. They want to be left alone to put together their puzzles, but they also depend on the public and the tribes for discoveries and access.

In July, the state announced that the site would be marked with buoys. Boats and swimmers can go there, but they can’t linger. Anyone who tries to dive at the site without permission will be stopped quickly, says McCarthy. “The local homeowners were some of the first people we invited into the conversation,” he says. “One gentleman who lives near the site has a telescope big enough to read the serial number on your snorkel. He’ll phone it in, we will figure out which store you bought it from, and the cops will be talking to your mother before you get out of the water.”

There are lots of other ways for nonprofessionals to get involved with archaeology. The best place to start is Florida’s Public Archaeology Network, flpublicarchaeology.org. If you happen to find a bone and you suspect that it’s human, call the police.