The Lavish Life and Forgotten Legacy of John Ringling North

Everyone in Sarasota knows the story of John Ringling. He’s the founding father who put us on the map, with his flamboyant mansion, his wife Mable, his art collection and most of all his circus. He created the idea of Sarasota as a place of beauty, wealth and sophistication, and his spirit can still be found all over town.

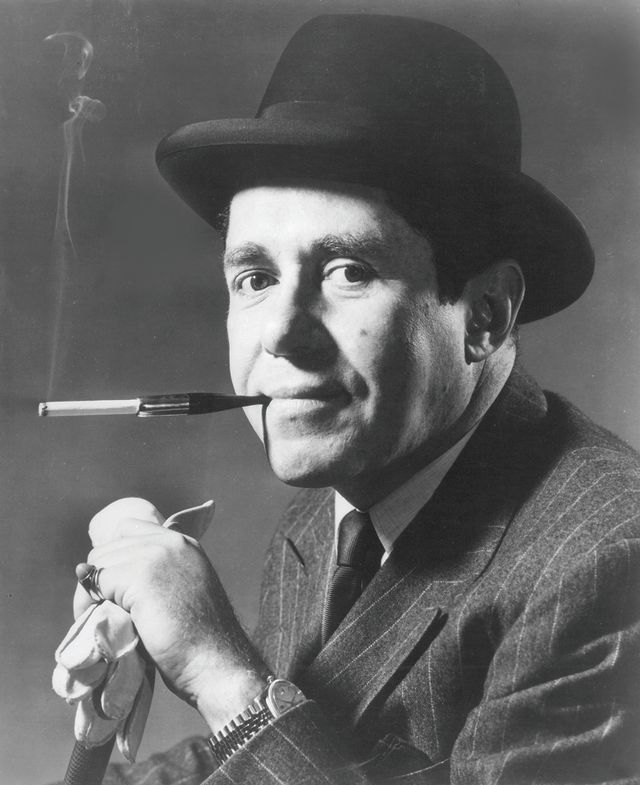

John Ringling North

But what about his nephew, John Ringling North? He ran the circus during its heyday in the 1940s and ’50s and lifted it to artistic heights that surpassed even those of his uncle. But today he is virtually forgotten. There are no statues to his memory, and when his name does come up people are confused. Some think he and his uncle were the same person. He’s been lost in the jumble of history.

It’s a shame, because his accomplishments in popular culture are unique. As a showman he perfected the circus as an art form. As a celebrity he kept the tabloids busy reporting his amazing lifestyle—he lived in a private Pullman car, dated beautiful women, and counted the other major celebrities of the day—everyone from Ernest Hemingway to J. Paul Getty—as his friends. His direct influence on Sarasota was much subtler than his uncle’s, but he gave the town a big jolt of creative activity. And glamour. One might say that was his biggest contribution—he glamorized Sarasota.

John Ringling North was the son of Ida Ringling. There were seven Ringling brothers (five were partners in the circus.) But Ida was the only sister, and in keeping with the male-centered world of the family, she was kept out of the business. She married Henry North, who worked for the railroad, although he came from an aristocratic Irish background.

John was born in Baraboo, Wisconsin, then home of the Ringling circus, in 1903. His was a wonderful childhood, and one that he never really outgrew. He knew all the performers and roustabouts, and they doted on him. The circus animals were, in effect, his pets. He was particularly interested in music and hung out with members of the circus band, learning to play various instruments. But most important, his uncle recognized his talents and his ambition. He was singled out among his various cousins as the one to watch. Soon his famous uncle became his mentor, schooling him in circus lore and business.

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

When the circus moved to Sarasota in the 1920s, so did he. He lived with his mother in her castle-like residence on Bird Key—the only house there—but most of his time was spent at Ca’ d’Zan. He saw firsthand the glamour—and power—of his uncle’s life. Fortune magazine called John Ringling “the best millionaire alive,” and Ringling certainly tried to live up to the title. There were celebrities, yachting trips, parties and all the other accouterments of a Great Gatsby-like existence.

His uncle paid John’s way through Yale (where he taught classmate Rudy Vallee how to tap dance), but he left college early and came home to work for the family business. He learned all aspects of not just the circus but his uncle’s real estate holdings. It was boom time in Sarasota, and the young man was making as much as $10,000 a day selling land in developments that were controlled by the Ringling family.

John Ringling North just missed being handsome, with a round, slightly pugnacious face. But he emulated his uncle’s impeccable style—homburg, gloves, cane and cigarette holder. He also had his uncle’s eye for the ladies. An early marriage lasted two years and left little impression. After that his conquests were many. The playboy image would stay with him his entire life and make his love life constant fodder for the tabloid press.

But the Roaring ’20s were beginning to turn rocky. Mable Ringling died in 1929, and when she was gone John Ringling lost his bearings. There were bad decisions, tax problems—he owed the government $13 million—the Depression and then a stroke. The problems caused a rift between uncle and nephew. The older man thought the younger man was trying to take things over.

He may well have been right. When Ringling died in 1936, he left his nephew nothing. But he gave him something better. His will made him co-executor of the estate. This meant that at age 35, John Ringling North was in charge of the circus. His goal: not just to keep it running but to re-invent it.

By the late 1930s the circus was struggling. The Depression cut into ticket sales. Some performances would see just a few hundred people in a tent that could hold thousands.

But it was more than economics. Tastes were changing. John Ringling was part of a tradition that went back hundreds of years but that was becoming increasingly old-fashioned. Now there were movies, popular music, radio, Broadway—a booming entertainment business that made clowns and elephants seem a little corny.

North brought the circus up to date. He painted the tent a deep blue, allowing for breathtaking lighting effects. He brought in 50 showgirls who performed aerial ballets. The best designers from New York and Hollywood were hired, and they journeyed to Sarasota each February to create a new show.

North with some of the beautiful showgirls he brought in for an aerial act.

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Each production had a distinctive theme, introduced by a spectacular opening number. The best acts from all over the world were there, carefully sequenced for maximum effect.

New acts were North’s specialty. He would sign them and they would move to Sarasota. Many of them would stay permanently. Hundreds of their descendants still live here today.

Each off-season he would journey to Europe, where his chauffeur would drive him and his current girlfriend around the continent looking for talent at circuses, fairs and nightclubs. Particularly nightclubs. He enjoyed drinking and gourmet food, hanging out with famous people and telling his stories all night long. “He had the stamina of a chorus girl,” said novelist Robert Ruark.

He lived this way his entire life. Months traveling around Europe by chauffeured Cadillac, winters living in the famous private Pullman car out at the circus’ Winters Quarters, and the rest of the time traveling with the circus. In each town he was treated like royalty, and the rich and famous clamored to meet him. Many became friends and visited him in Sarasota. These included Hemingway (the old Sai Woo restaurant on the North Trail, now Barnacle Bill’s, used to brag of his patronage) and Prince Rainier of Monaco, who dropped by on his way to California to propose to Grace Kelly.

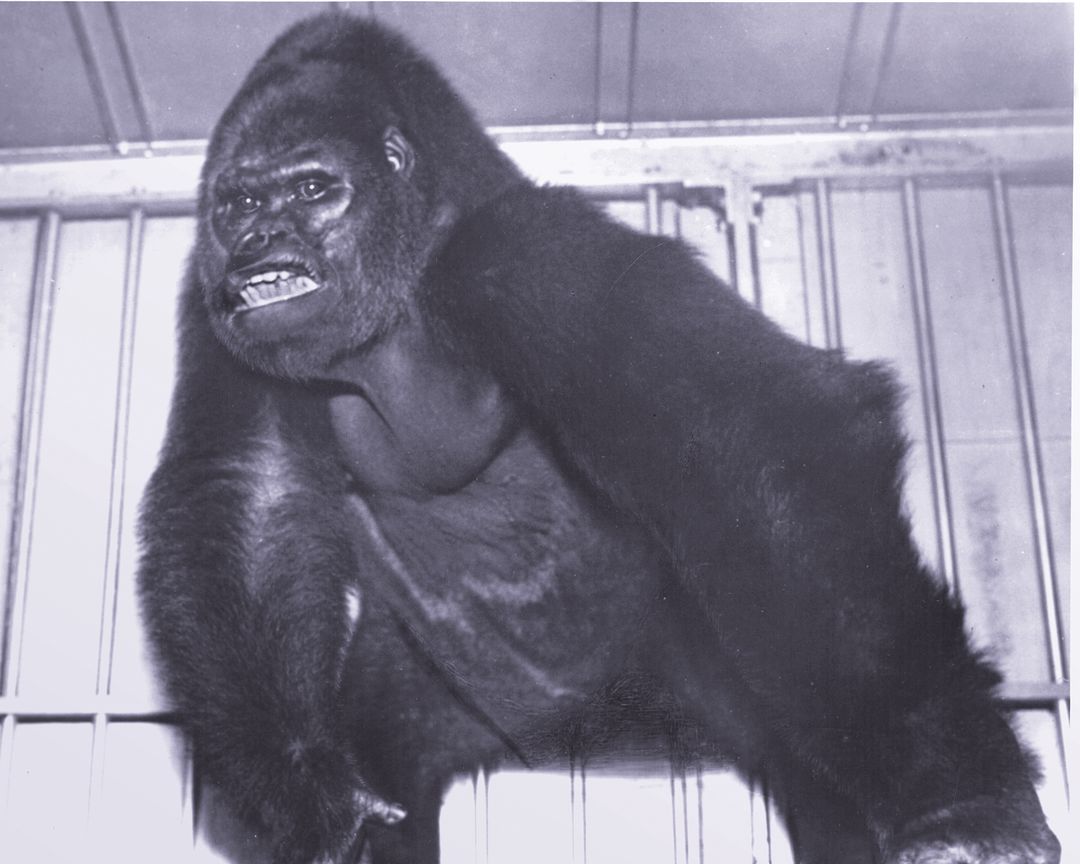

Gargantua the gorilla

North brought sophistication to the circus, but he did not forget he was first and foremost a showman. The ballyhoo was still there, particularly when it came to Gargantua, the 550-pound gorilla who was for a while Sarasota’s most famous resident.

Billed as “the largest and fiercest gorilla ever brought before the eyes of the civilized world,” Gargantua was acquired after a phone call from a woman in Brooklyn who wanted to know if the circus could use her gorilla, as he was getting too big for the house. Gorillas were a rarity at the time, and the ape caused a sensation. Many circus scholars credit the beast with saving the circus from bankruptcy.

North carried the ballyhoo as far as he could. He even got Gargantua a wife, a more demure female named M’Toto. As luck would have it, the two hated each other and instead of mating as hoped, they pelted each other with melons. Gargantua, ever the trouper, died just after the last performance of the season in 1949. M’Toto’s home, with its distinctive 79-foot-long room designed to mimic the train car she rode in, still stands on Virginia Drive in north Sarasota.

The artistic climax of North’s career was undoubtedly the Circus Polka. He commissioned Igor Stravinsky to write the music for a ballet performed by 50 elephants, with famed choreographer George Balanchine to direct. The extravaganza, which debuted in 1942, was a sensation, the perfect meeting of high art with low art. Critics were astonished at its beauty and inventiveness. Now the circus was more than the circus. It was “art.”

There was only one mountain left to climb: Hollywood.

Betty Hutton swings on the trapeze in the Oscar-winning The Greatest Show on Earth, filmed in Sarasota.

Image: AF Archive/Alamy.com

The idea for a major motion picture about the circus had been kicking around for years, but it wasn’t until 1951 that all the elements came together. The legendary Cecil B. DeMille would direct. Stars like Charlton Heston, Betty Hutton, Dorothy Lamour, Cornel Wilde and Jimmy Stewart were signed to play archetypal circus people—the rival aerialists vying for the center ring, the tough showgirls, the ruthless company manager, the mysterious clown who never takes off his make-up. They all descended on Sarasota in January 1951 and for the next six months the town became a veritable film studio, with just about everybody in town participating as extras in the numerous crowd scenes filmed at the Winter Quarters and on Main Street. John Ringling North played himself, or rather an idealized version of himself: wise, concerned for all, a good boss.

The Greatest Show on Earth is treated a little condescendingly by film buffs today. They can’t get over the fact that, with all its corn and bright colors, it won the Oscar for best picture over competition that included High Noon and Singin’ in the Rain. It was also the most financially successful picture of the year, not just in the U.S. but in Europe as well.

It was great popular entertainment, but today its chief pleasure is the fascinating picture it gives us of the circus—the John Ringling North circus—at its peak. It’s all there—the enormous blue tent that took hundreds of roustabouts to raise, the endless parades, the gaudy costumes, the clowns, the sideshow freaks, the sheer frantic activity and noise. And most of all, the animals.

Back then no one considered the circus’ treatment of its animals cruel or inhumane. That’s the way things were. Lions were threatened with whips, elephants were poked and prodded. It didn’t occur to anyone that Gargantua was mean and ferocious because he was confined to a cage and, in effect, tortured for most of his life. It was a miscalculation that, when it came to the forefront of public consciousness, would doom the circus.

We can see the other seeds of its eventual demise in The Greatest Show on Earth. In North’s big scene, where he and his managers plan the upcoming season, the news is dire and it all comes down to money. Can they afford the gamble of playing a long season, with dates in small towns? Or have TV and movies shrunk the audience so that only playing big cities is feasible? Labor expenses are skyrocketing, with union problems getting worse and worse. The manpower for erecting the enormous tent, then taking it down, has become crippling. So have transportation costs. With 1,500 cast and crew members, a full-scale zoo, and scores of tents that must be set up at every venue, the circus is no longer economically viable.

North tried his best. His first big step was to abandon the Big Top. In July 1956 he made the decision that the circus would now play in arenas and stadiums. “The tented circus is a thing of the past,” he told reporters.

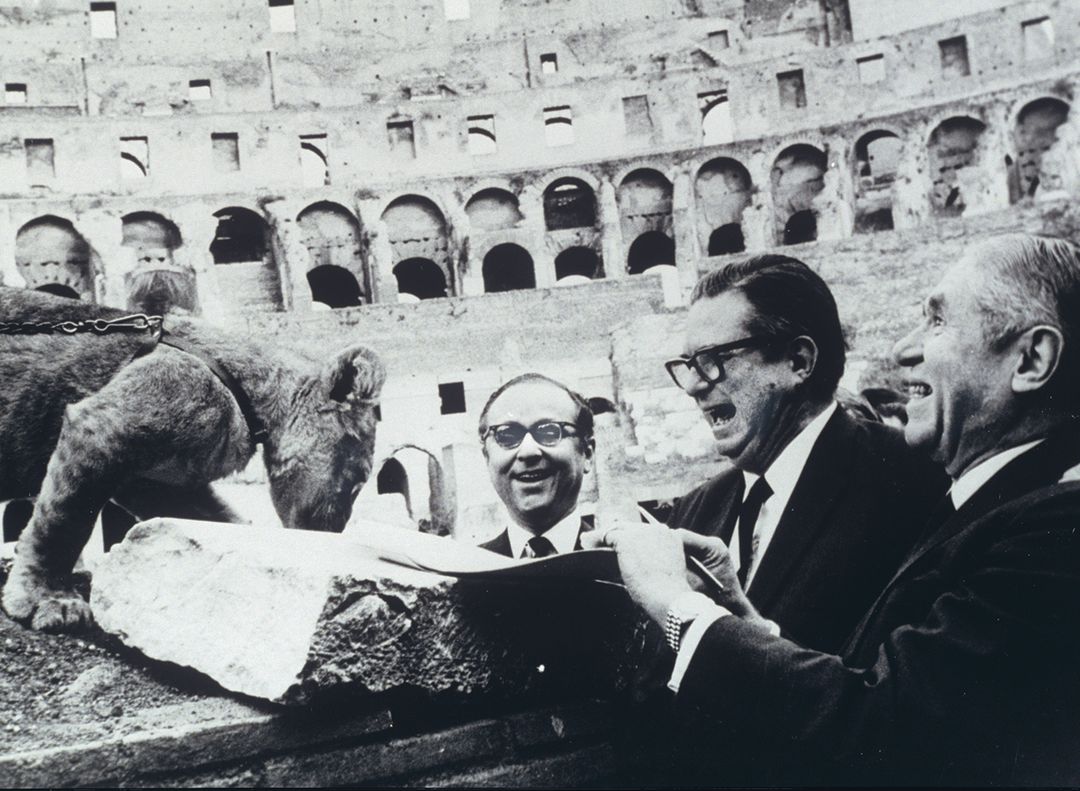

Irvin Feld, Israel Feld and partners acquire Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey at the Colosseum.

He kept trying for another 10 unhappy years. Crowds continued to dwindle and costs kept going up. Even worse, he was blamed by many in the circus community for all its problems. He made it too modern; he abandoned time-honored traditions. Finally it became too much for him. In 1967 he sold Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus to Irvin Feld, a promoter who had been working with him, for $8 million. The sales agreement provided him with a lifetime salary. Earlier, when Ringling properties in Sarasota—Bird Key and southern Longboat Key—were sold to real estate developer Arvida, he pocketed several million dollars more.

Wealthy but ignored by the world that he once ruled, North retreated into a peripatetic existence in Europe. He and his brother bought their father’s ancestral home in Ireland and North became an Irish citizen.

His womanizing days were over. Gone were the beautiful girlfriends—Gloria Drew, Dodie Heath and others—who had become fixtures in Sarasota and on the circus train. Now he lived with a German countess named Ida von Zedlitz-Truetzschler. He had romanced her in his heyday. They settled into a loving and companionable relationship, living in hotels and apartments in Europe, never quite settling down but turning into what one observer described as “an old German couple frying chicken in their hotel suite.” He died in 1985 of a stroke at his favorite hotel in Brussels. He was 81 years old.

Sarasota is full of tangible reminders of John Ringling. Streets, bridges, a palatial home, a museum. Of his nephew there is barely a trace. He never owned a home here; in fact, his Irish estate aside, he never owned a home anywhere. He did own the John Ringling Hotel, for years Sarasota’s finest. In its ultramodern M’Toto Room, North could frequently be heard playing the saxophone with Rudy Bundy’s orchestra. But the hotel was torn down in 1998 and along with it another piece of his legacy.

Inside the opulent Jomar

There is one small reminder, though. Against all odds the Jomar, John Ringling’s private railroad car, which was transferred to North, still exists. North ripped out the mahogany paneling and Tiffany windows and installed a stylish late-Art Deco look. Here North entertained the world’s elite, aided by a valet, chef, maid and chauffeur.

Today the Jomar is part of an eccentric restaurant/tourist attraction run by Bob Horne, who happens to be Rudy Bundy’s grandson-in-law. The four railroad cars Horne has collected over the years are crammed with memorabilia. Much of it concerns North at his peak.

“He was a perfect gentleman,” Horne recalls. But one who never got the credit and respect he deserved. Even the Jomar, currently a rusty and decrepit wreck, will be restored to the way it was during the uncle’s glory days, not his nephew’s. All that remains of John Ringling North are some faded photos and newspaper clippings—and the gold pen with which he signed away his circus in 1967. He insisted that the ceremony take place at the Colosseum in Rome. Even in defeat he remained the perfect showman.