The Collapse of The Colony

Editor's note: Dr. Murray "Murf" Klauber passed away in 2018, the same year the Colony Beach & Tennis Resort was demolished. The property will soon be the site of the St. Regis Longboat Key.

Back in 1967, when 40-year-old orthodontist Dr. Murray “Murf” Klauber first saw The Colony Beach Resort on Longboat Key, he was smitten. It was winter, and Klauber had been preparing to fly out of his frigid hometown of Buffalo, N.Y., to deliver a speech at an orthodontics conference in St. Louis. Then his first wife, who had been staying on Longboat Key with friends, called. She urged him to take a quick detour to this beautiful, largely undeveloped island in the Gulf of Mexico.

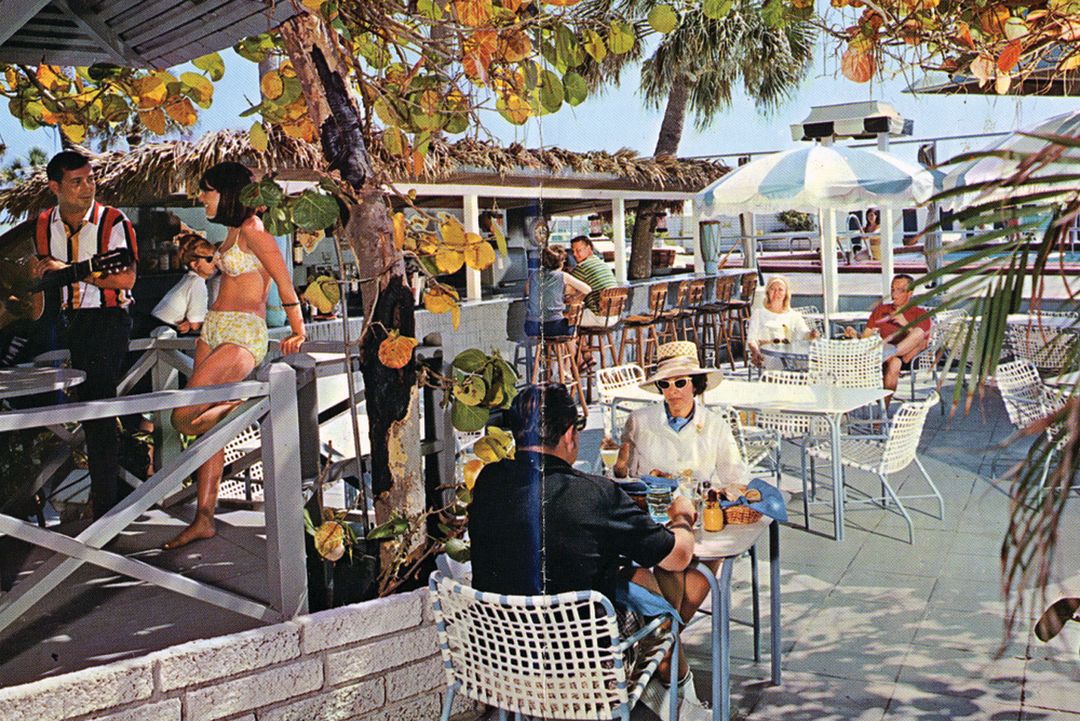

Klauber arrived in Sarasota about 11 p.m. and drove to The Colony, which was then a collection of charming beach cottages and a popular restaurant and bar. Built in 1952 by Sarasota developer Herb Field, the resort already had a national reputation for its Bohemian beach elegance, its all-Black wait staff who served flaming tableside dishes, and a Juilliard-trained pianist who played jazz while regulars like novelists John D. MacDonald, MacKinlay Kantor and Borden Deal chatted at the bar and women in long gowns flowed into the dining room for dinner.

“In the morning I went down to run the beach,” Klauber says. “There was nothing north of us and nothing south. You’d jump over fallen trees and see the birds, and it was so magical. I said, ‘What am I doing in Buffalo? This is a mecca for the right kinds of people.’”

He was right.

The Colony that Murf Klauber envisioned—a pioneering luxury condominium-hotel centered around tennis—and then built and ran for almost 42 years became a beloved getaway for hundreds of condominium owners and tens of thousands of guests. It helped put Longboat Key and Sarasota on the international map, launched the career of tennis coach Nick Bollettieri, who started his tennis academy there, and won national tourism awards. Affluent people from all the over the country who fell in love with The Colony’s laid-back elegance ended up buying their own homes nearby.

But in August, it all collapsed. After a six-year battle between Klauber and the owners of the condominiums at The Colony, a federal bankruptcy judge, who some said seemed exasperated with the bitter and convoluted legal case, gave control of The Colony to the condominium owners, ending Klauber and his family’s four-decade, day-to-day immersion in the property.

A month later, Klauber, 83, was still living in his penthouse there, wearing his trademark colorful resort-style shirts and wandering an eerily empty property. His wife, Sue, a Canadian, was still in Canada for the summer. A sign at the entrance stated simply, “Closed.” “No Trespassing” signs and orange cones prevented people from driving or wandering onto the quiet property.

“It looks like a deadly virus hit the community,” remarked a man who was standing on one of the sandy roads near the entrance. No one was playing tennis on the courts or sunning on the beach, no cars were parked in front of the units, no kids splashed in the pool, no beach towels hung over the banisters.

“Forget about the 42 years and all the lives we’ve touched,” Klauber says, shaking his head about the court decision. The hot-tempered, combative dreamer, who could come up with outrageous strategies to make his deals work, seemed strangely subdued. “It is emotional, and it’s unfair.”

His attractive and crisply professional daughter, Katie Klauber Moulton, 53, the president and general manager of The Colony since 1988, stood by his side. “And it’s unfinished,” she adds.

What happens to the 18-acre Colony now is as big a tangle as a bunch of necklaces thrown in a drawer.

“This is a classic case of ‘Be careful what you wish for,’” says Morgan Bentley, a Sarasota attorney with Williams Parker. Bentley represents Carolyn Field, the widow of the original Colony developer, and William Merrill, Klauber’s Sarasota attorney back in the ’70s, who own a small portion of The Colony’s property. “It’s a life lesson—the law of unintended consequences.”

Publicly, The Colony began to fall apart in 2004. But to understand the dispute that divided the Klaubers from their condo owners, you have to go back to the beginning.

The Colony Beach & Tennis Resort was set up as a condominium-hotel in 1973 and was registered with the SEC as an investment. If you purchased one of the 237 units back then—starting prices were about $40,000—you were not just a condo owner; you were also a limited partner. You could use the property for 30 days every year and had to put your unit into the hotel rental pool for the remaining 335 days. The Klaubers say this was the first condo hotel of its kind in the country and has been copied around the world.

From 1973 to 1984, Klauber, as the general partner and manager, gave the owners an annual cash distribution. He split the profits 50/50 between himself (acting as the manager) and the owners after he had paid expenses; owners were responsible for paying their own taxes and insurance on the units and paying assessments to the association.

Klauber then used the assessments to maintain the property. As manager, he also took care of the interior of the units, since each had to meet the same standards in furnishings and equipment if he were to successfully market the resort as a luxury destination.

That all changed in 1984. Under a new arrangement, Klauber would pay all the taxes, insurance and maintenance costs as well. If there were any profits after that, they would be split 50/50.

Why the change? Klauber’s attorney, Charles Bartlett of Icard, Merrill, Cullis, Timm, Furen & Ginsburg in Sarasota, says the condominium owners initiated it for tax reasons so they didn’t have to pay taxes on the annual distributions. The new arrangement also worked to Klauber’s advantage, since he didn’t have to go to the association for every expense.

After 1984, there were few cash distributions, but until 2004, most unit owners and their condo association seemed reasonably happy. They were paying no taxes, no insurance and no maintenance, and they got 30 days’ use of a beautiful property on the Gulf of Mexico with all the niceties that any hotel guest would receive—a value worth $35 million from 1987 to 2009, according to Klauber and Moulton. While it puzzles many observers that The Colony was not distributing any annual profits to the owners—“How did Murf manage to keep them happy?” asks one baffled Sarasota attorney familiar with the setup—the units could sell, and often did, for more than the original purchase price.

And then in 2004, Klauber and Moulton decided that they needed $12 million to renovate The Colony. Tourism had been shaky since the 2001 terrorist attacks, and after a series of hurricanes hit Florida in 2004, hotel bookings took another dive. In addition, tennis was no longer the draw it had been in the ’70s and ’80s. Most significantly, the property was now more than 30 years old; it was looking shabby and also needed to be upgraded to withstand major storms.

The pair told the board that they didn’t have the money to pay for these repairs and renovations, and it was time for the unit owners—after enjoying a free ride for many years—to reach into their pockets and contribute a one-time $50,000 assessment per unit.

As Klauber and Moulton saw it, their request was reasonable and in accordance with the founding documents of the condominium declaration, which they insist specified that unit owners were required to maintain the exteriors of their units.

But that’s not how most of the owners felt. Twice—in 2005 and 2006—the association board, which agreed with the Klaubers’ plan for improvements, asked the owners to approve the assessment, and twice the owners voted it down. An angry group of owners began to organize, and in 2007, those owners took over the board.

A series of lawsuits, mediations and a temporary closing of the hotel in 2009 followed. In 2007, Klauber sued the owners to compel them to pay the $12 million. The association responded by filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy for itself later that year. Minority owners William Merrill and Carolyn Field also got pulled into the court case. Eventually, Klauber and Moulton—operating as the hotel managers—filed for Chapter 11 for the hotel.

The association won just about every court battle. Most significantly, in 2009, Judge K. Rodney May ruled that the association was not obligated to pay the $12 million bill. Klauber and Moulton responded by closing the hotel for several months. In May 2010, the judge said that he saw very little hope that The Colony could continue under the Klauber family management. While he praised Moulton’s management skills and said he wasn’t “questioning anybody’s motives,” May said that Klauber had created a way of budgeting that included “self dealing” and “gross mismanagement,” and he cited conflicts of interest in the way the hotel’s accounting system operated.

For example, the judge said that Klauber had used revenues from the hotel to pay expenses that benefited his own businesses. Further, May didn’t see any feasibility in the reorganization and noted that the property was deteriorating.

By Aug. 10, the judge said he had seen enough and converted the Chapter 11 to a Chapter 7, which meant that the Klauber family-led partnership would be liquidated. The hotel closed with a big good-bye party four days later with well-wishers and longtime Sarasotans lamenting the end of an era.

To both Klauber and Moulton—who continue to insist that they had every right under the condominium operating agreement to assess the owners and conducted business honorably—it is a sad and bitter ending to a business that they nurtured and loved and that became a landmark on the west coast of Florida. The legacy that Moulton stood to inherit after decades of work—starting as a Colony dining room water girl and hostess in long dresses when she was 12—is gone.

“I tried to prepare myself for so long,” Moulton said right after the decision. “I didn’t want this. I’m walking away with the satisfaction that we created a magical experience. [But] God knows it hurts.”

Money and larger-than-life personalities played a pivotal role in the battle between the family and the unit owners. Klauber is known for his magnetic charm and entrepreneurial energy—and also for his hot-headed impatience and a refusal to compromise.

Called “a dictator” by a detractor and more gently described as one who “always thinks he’s right” by a friend, he’s known for embracing grandiose ideas, such as the futuristic, high-tech conference center he once proposed for downtown Sarasota and then tried to develop in Tampa, and for filing lawsuits, such as the civil rights action against the Town of Longboat Key that earned him $6 million—and plenty of enemies.

Some of those involved say that Klauber could have headed off the court case if he had compromised by offering the association more control or profit-sharing. Instead, convinced he was right, he refused to yield an inch.

On the other side were the unit owners, many of them well-heeled executives and entrepreneurs who were used to calling the shots in business and life. After decades of not having to pay expenses, they were shocked and angry when they were told that the Klaubers could no longer pay the bills. How could this be possible?

Schenectady patent attorney Jay Yablon, 56, a unit owner who took over as president of the board of the condominium association in 2007, remembers learning about the assessment in 2004. “Within 24 hours, I had an e-mail sent out [to all the other owners],” he says. “There was no organized movement at this point, but very quickly owners coalesced.”

It is not difficult to create suspicion and dissension, says Salvatore Zizza, a Manhattan-based investor, chairman and CEO of multiple companies who was president of the condo association before Yablon took over. He believes the condo documents made the owners responsible for the renovations.

“When you’re used to getting something from Mom and Dad, it’s tough,” he says. “The board did not want to hear it.” The unit owners, he adds, became convinced that Klauber was overcharging and hiding money.

Yablon counters that it was time for a new board. The old one was filled with Klauber’s cronies, he claims, who would rubber stamp almost every request he and his daughter made.

Zizza, 69, laughs at the comment. “I’m a successful, sophisticated businessman,” he says. “I’m in the real estate business. I built, own and operate major international construction businesses. Murf has never been a businessman. He’s a dreamer. I’m going to allow Murf to tell me what to do? I own two units. I’m going to devalue my units? I don’t think so. The condo document was very clear who was responsible for the interior and who was responsible for the exterior. Anyone who says they were duped didn’t read the documents.”

The new board includes its share of power players. Besides attorney Yablon, who owns two units, there is Robert “Andy” Adams, chairman and CEO of National Healthcare Corporation, a public long-term care company based in Murfreesboro, Tenn.; and Ruth Kreindler, the widow of Lee Kreindler, a leader in aviation disaster whose New York firm handled almost every major airplane disaster—such as the Pan Am Lockerbie bombing—for 50 years.

“They hated Murf with a passion,” Zizza says of the new board. “When emotions get involved, there’s no solution.”

Yablon says his hope is that the condo owners can rebuild The Colony as “a condo-style hotel again, not dissimilar to The Colony.” He and the association’s heavy-hitting Tampa attorney, Jeff Warren, who’s known nationally for his successful bankruptcy work in the billion-dollar Celotex case and who racked up $2 million in legal fees litigating for Yablon and the association, recognize they face serious challenges. However, they say, at least the unit owners now have control over their destiny. “It’s the right of self-determination,” Warren says.

Bartlett, the Klauber family’s attorney, doesn’t think that will get them very far. “I said three years ago if the association gets its way it will be like the dog that caught the car. Well, it caught the Mack truck, and now it doesn’t have the first idea of what to do. The notion that it will reopen is almost comical if it weren’t so sad. They’re like a bunch of Boy Scouts trying to build a nuclear weapon.”

At the most basic level, the unit owners must now take responsibility for keeping the property in good condition and learning to pay the bills.

“They never had to lift a finger,” says Moulton. “The plumbing always worked, and the ice was always delivered. The trees were always trimmed, and the flowers were blooming. There was always a tennis match waiting for them, and there was a lovely person at the pool desk who remembered their name and handed them a towel. They had no idea of the effort behind it all. They got their first citation from the town for not mowing the grass at the entrance. Now they’ll understand what it cost to keep the sewer working, to maintain the landscaping and the roads and their units and keep the icemaker working.”

In addition, Klauber still controls three of The Colony’s 18 acres—or, as he puts it, “all the working parts.” He is the sole owner of two penthouses, the 17,000-square-foot restaurant complex, a beach cottage, two office buildings and a big chunk of the mid-rise building plus 80 percent of the 12 tennis courts, the swimming pool, the hotel laundry, an office and a building that contains meeting rooms and a gym—what are known as the recreational facilities and without which there is no resort.

Carolyn Field owns 15 percent of these facilities and attorney Merrill owns the remaining five percent. They have sued both the association and Klauber and Moulton in their roles as managers for using the facility for hotel guests without paying rent for a year and a half.

Klauber declares that he intends to stay in his penthouse, right in the middle of everything. “To get rid of me, they’ve really got a problem,” he says.

Yablon says that while the board would like to buy these three acres—everything is for sale in the end, he says—they will not overpay, and that Klauber and the minority owners are asking too much. Klauber alone is asking about $22 million, according to several of the players.

But others want to be paid as well. Randy Langley, a Longboat Key entrepreneur and owner of Cedars East Tennis Resort on the north end of the key, and David Siegal, an attorney who also lives on Longboat, took a gamble and bought Klauber’s mortgage from Bank of America. Langley and Siegal will not confirm the amount they paid, but it is believed that they bought a $10 million note for somewhere between $4 million and $5 million.

And while some speculate that the bank was anxious to get rid of the note because it knew the value had slipped, Siegal and Langley saw potential. For an additional $20 million investment—hopefully coming from the unit owners—they said they would develop another five-star luxury resort on The Colony’s 18 acres.

The deck is stacked against them. At press time, the association was not leaning toward choosing them as the developer, and now that the judge has liquidated the hotel, the value of their investment has gone down. Nonetheless, they will at least try to make a profit on the initial $4 million or $5 million. They have already started foreclosing on Klauber (who is in default on the loan) and although they’ve offered to forgive his debt and let him live in his penthouse on the property—a deal Klauber has so far refused—they will try to protect their investment by selling the note to another buyer for more money than they paid.

Yablon says the condo owners will work around Klauber’s property if they can’t buy it. However, that won’t be simple if the owners want to rebuild. Without the recreational facilities, The Colony might not have the required “green space” for 237 units. The Town of Longboat Key’s zoning code might only permit 90 units on the owners’ property. And a rebuild could also trigger FEMA regulations that would require more setbacks and height restrictions.

A Karins Engineering Group report, commissioned by the association, concluded in September that the property needs an immediate $600,500 to make it safe enough to reopen. If the owners want to restore the existing buildings and units, making them structurally sound for years to come, Karins’ estimate is $19.6 million, much higher than the $12 million Klauber and Moulton asked for six years ago. To demolish the buildings and construct a brand-new resort with 282 units would cost at least $54.4 million, according to the report.

Bartlett says that unless something is done soon, the units will continue to deteriorate and become uninsurable. A hurricane could wipe out the property, and the owners would have no insurance to cover their losses. “I bet you it will never reopen,” he says.

For now, Yablon and the board are trying to see if they can get enough of the units in working order so that owners can start staying there as early as this winter. Yablon believes some units are unusable at this point because equipment and A/C units may not be working. Mold and termites have also been detected. Meanwhile, the legal wrangling is far from over as every party continues to fight in court over what remains.

Yablon reacts calmly to the list of roadblocks, not the least of which is controlling 237 homeowners who now want a say in how things are run. “We’ve created 237 monsters who start out, ‘I own my own unit. Yeah, it’s a fixer upper. But what are you going to do for me if I put it into the rental?’” Yablon admits. “What inducements can be given to these 237 monsters?”

Yablon sees Murf Klauber as a tragic figure. “Go watch a Shakespearean play about somebody who achieves greatly, but the rules that apply to the rest of us don’t apply to him. They get arrogant and overreaching. It’s a classic story.”

But hubris exists on both sides. As attorney Bentley sees it, the board feels like, “We just got rid of Saddam Hussein.” But on the other hand, the $50,000 that Klauber originally asked for would be a memory at this point. “Now look at what they have,” Bentley says. “They could have had a nice place two years ago.”

The association’s attorney, Jeff Warren, when asked what lessons be should taken away from this case, reflects a moment and says, “Read the fine print. People don’t look at what will go wrong in a business deal.”

Nothing lasts forever, of course—including iconic institutions and personalities and businesses. Influential and powerful as they may be in shaping our communities, they will eventually crumble and disappear. Sooner or later, something new will emerge on those 18 acres of prime Longboat Key real estate overlooking the sparkling Gulf of Mexico.

Klauber and Moulton are not sharing any details about their future right now. Characteristically, Klauber says retirement is not in the picture. “Maybe when I grow up and get older. Right now I’ve got a lot of momentum.” And he adds—with a mischievous grin—“I’ve got another plan I’m working on.”

Moulton says she wants to focus on community service in Sarasota, mostly doing child advocacy work, and she’ll eventually go back into the hospitality industry. “I’m just not sure exactly what yet,” she says. “I need to take some time off. I never let go; never ever let go. I could have been in South Africa or Timbuktu—wherever I was, I was always connected to The Colony.”