What It's Really Like to Hunt Burmese Pythons in the Everglades

Florida often seems tame, a place of beach resorts, condos and Disney World. But not too far off the beaten path, often in our back yards, the wilder side of the state scampers, slithers and grows. In the new anthology, The Wilder Heart of Florida, 34 writers tell tales of the fragile, beautiful and strange nature around us and why it’s worth protecting. In this reprinted essay, originally titled “Feast of Pythons,” Isaac Eger heads out for a moonlit night of python hunting in the Everglades.

I asked, “How will I know when I see one?”

Somewhere deep in the Everglades, I pointed the spotlight at the night ahead of the truck that carried us along the crushed limestone path of Levee 28.

“It’s just one of those things you’ll know when you see it,” someone said.

The levee’s road ran so straight for so long that the light got gobbled up by all the dark and looked like it might go on forever. I pointed the light back to the levee’s banks, looking for something that wasn’t supposed to be there. We were python hunting. Trying to make Florida natural again.

The truck belonged to a real Florida boy, some generations deep, whose name, I shit you not, is Dusty Crum. Dusty, who lives in Sarasota, is a famous python hunter. He’s got his own TV show, except on the show they usually hunt during the day and on foot. But the snakes are most active at night. When all the other critters are out. There weren’t any other critters tonight but for an occasional palm rat. The snakes had eaten most everything else.

Dusty’s 38 years old, but you might confuse him for someone much older. Not because he looks old—though he’s got a lot of gray in his beard and long hair that falls under a dirty baseball cap—but because he looks like he belongs to the land, and the land in Florida seems ancient, like something the dinosaurs might have enjoyed.

I asked, “How many snakes are out here?”

“A lot,” Dusty said. “Hundreds of thousands.”

Between 100,000 and 300,000 Burmese pythons live in the Everglades.

Image: Peter Fisher

Nowhere on earth do invasive species thrive like they do in Florida. It only took about 20 years for these pythons to eat damn near everything and usurp gators as the apex killer. Native species don’t stand a chance. I, too, am a Florida native—a fact I’ve begun to parade around now that Florida is literary hot shit. A fact that might not seem so meaningful since this is my first time actually setting foot in the Everglades. I’d driven through it, many times, on that 80-mile-long concrete lesion we call Alligator Alley.

But I’m here, trying to get my bona fides, hunting invasive Burmese pythons, trying to save what’s left of what Florida’s supposed to be because the Florida I grew up in turns out to be a counterfeit.

Florida is a strange land full of strangers. When I was young it was the tourists who were the foreigners, and all the little precious creatures and trees I loved from my childhood, these things that I believed were here before we had a name for anything, were true Florida nature. Then I learned that I’d loved invaders. Brown anoles from Cuba. Australian pines. Those tadpoles I’d gather after a hard rain, fed lettuce to and released back into the wild—those were Cuban tree frogs that swallowed our smaller native species whole. The once beloved things of my childhood I must reimagine as marauding aliens, corrupting the balance of what was supposed to be.

So here I am. Making up for it. Making Florida natural again.

Dusty’s girlfriend Natalie drove the truck. She chain-smoked Marlboro Golds while a beagle with a red bandana around its neck named Riley sat shotgun.

The truck ambled just fast enough so that the bugs didn’t bother us. You could still see them flying all around from the glow of the vehicle. The bugs turned white in the light we created and looked like a flurry of snow that didn’t know which way to fall. I sat in a chair propped up high in the middle of the bed of the truck. A long metal slat crossed the back of the truck so that two others could hang off either side and watch both the levee banks and quickly hop off if a python got spotted. Dusty was on the left, and his friend Gregory sat on the right.

“Back up, back up!” Dusty shouted at Natalie. He hit the roof of the truck with the flat of his palm.

The truck reversed. It was nothing. A fallen branch. Natalie put the truck back into drive.

“The pythons come up on the dry banks of the levee to lay eggs and hunt,” Dusty explained.

Snake hunter Dusty Crum

Image: AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee

Dusty learned that from firsthand experience—he isn’t a biologist. He’s only been hunting pythons since 2012, when a TV show sponsored a python removal competition. Dusty and his friends have taken it upon themselves to save the Everglades. Before they got state permission to patrol the levee, they’d ride their bikes up and down the levee during the midday summer heat. The snakes they caught would be too heavy—sometimes over 100 pounds—to carry all at once, so they’d have to go back and forth, carrying maybe one at a time.

Python skin wallets

Image: Fred Lopez

Now Dusty better knows the trade, and we chatted about the business end of things. How he might be able to turn a profit out of this endeavor of his. He’s skinning the snakes, turning their scaly hide into leather. Eating the meat. A Cambodian neighbor is turning the guts into some kind of traditional antiarthritic medicine. But the Asian market makes these snake pelts for pennies on the dollar, fattening them up in cages on snake farms like some kind of cold-blooded veal. It would be hard to imagine Dusty a rich man anyway. Always says he’s doing this for the land and not a buck. I believe him because he’s not cruel.

Dusty said, “It ain’t their fault. They’re beautiful creatures just doing what God created ’em to do. It’s not like I got anythin’ personal against ’em. I just care more about our native future.”

They have to kill them when they catch them. Used to be that Dusty would bring the snakes back to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission officials and they’d euthanize the pythons. Now he’s got to kill them in the field unless he runs into someone else who will do it for him. There’s a dime-sized kill spot on the top of their skull. A .22 rifle does it.

“It’s sad killing the little ones right when they hatch. They’re kinda cute,” Dusty said.

Besides the battery-powered spotlights in our hands, a bar of LED lights about two feet long was hooked to loose wires that led back to the engine of the truck.

“That’s some hucklebuck shit there, boy.” That’s how Dusty described his electrical setup. “Gotta make do with what you got,” he clarified. A lot of his truck he called hucklebuck, which is Floridian for jerry-rigged.

Not long into the journey down Levee 28, the lights died. Dusty and Greg popped the hood and peered into the smoking engine.

“Fuse is all fucked up,” said Greg.

“You done sabotaged me, son,” Dusty said, only sort of joking.

The moon swung just above our heads to the left, and the bugs started to land on us and taste our skin. The light rested in the bottom third of the moon like it was a bowl filled with white water.

“That means there are lots of fish ready to bite,” Greg told me. “And when the moon is gone, the snakes will come out.” He smiled.

There was a lot of optimism about this hunt.

The lights came back, and the truck went on.

It was hard to tell how much time had passed. So much of the Everglades was the same. A thick green loop interrupted only by the occasional dead amber of a fallen tree.

There were many sounds. Buzzing and clicking. Heavy drones and distant yelps. Sounds of things I didn’t know belonged to what.

I thought of all the things I didn’t know the name of. I knew the Burmese python, though. Why didn’t they evolve here if it serves them so well? It makes survival of the fittest seem inaccurate somehow. You can’t be too fit, I thought. Irony is, the Burmese python is threatened in its native habitat.

I never bothered to ask Dusty about politics. He wore a Don’t Tread On Me hat, and that could mean a few things. Conservation is conservative. I suppose when you live near the land, you’re going to feel it change first. Florida is changing, is changed. Dusty is trying to slow that change. But if you ask him if it’s possible to rid Florida of the pythons, he won’t kid you. The snakes are here to stay, are a part of Florida for however long Florida will be. News programs end their segments about Dusty with that affected cadence: These pythons . . . may have finally . . . met their match. But it’s only an act of God that could return the land. So fighting these snakes becomes symbolic. It’s a tangible opponent. The changing world is something beyond touch. You can’t be outside of a system and hold it while it holds you. But you can grab these snakes behind the mandible and drag them out of the world.

The truck veered off to the right. Natalie had fallen asleep. The three of us gave a holler and slapped the truck. We went down the embankment. I readied myself to abandon ship. She hit the brakes, and the truck stopped and then teetered. Fortunately, it wasn’t a particularly steep incline. If we had flipped, Greg would have been a goner. We got the truck out and back onto the road.

There’s something uncomfortably familiar about the fervor behind hunting invasive species. I’d hunted lionfish before—another invader menacing the waters of Florida. I’d killed them with a sense of righteousness. Fish, I am obligated to shove this spear through your face. I’d always felt bad about killing anything—even a fish—but because I was told this was a wicked fish, killing it was good and felt good. A promotional poster for the 2019 Tampa Bay Spearfishing Challenge crossed my social media feed.

Underneath an illustration of the Skyway Bridge is an excessively muscular merman with familiar blond hair in front of a wall. He’s pointing a gun at a spooked lionfish. The guy who posted the picture wrote: This is my new favorite depiction of my America. Merman Trump defending the wall with his Glock.

It was after four in the morning, and we hadn’t found anything. Everyone seemed disappointed—probably on my behalf. They wanted me to see the problem for myself. It seemed odd wishing to see the thing. Wasn’t it better that they weren’t there?

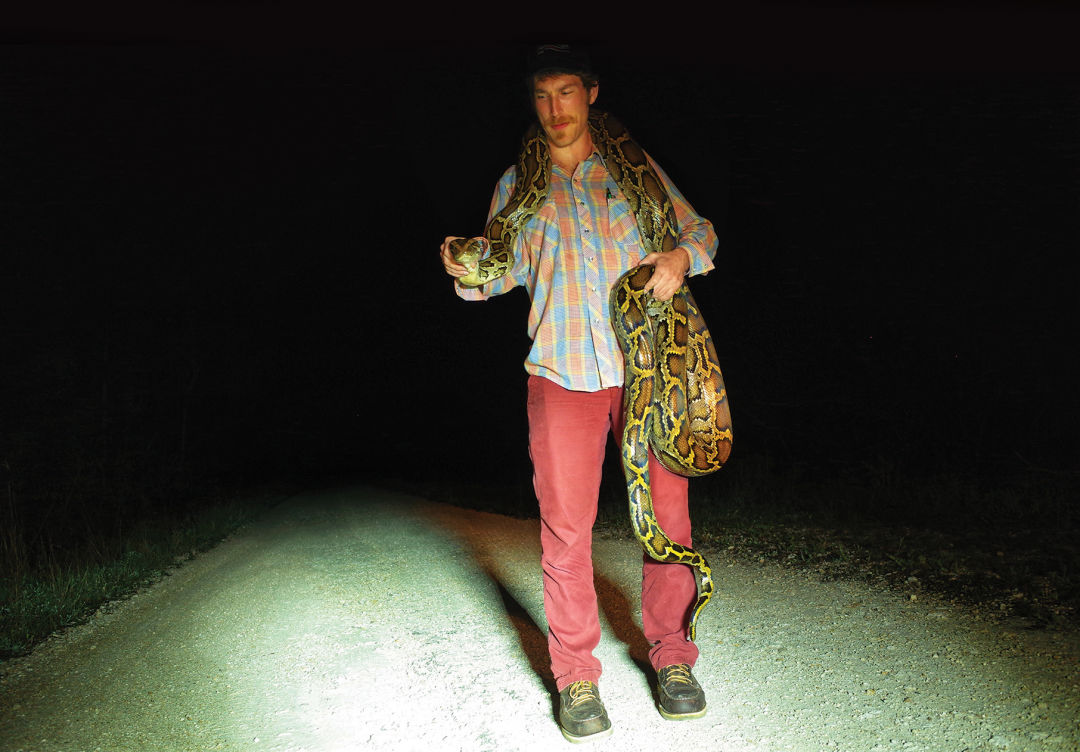

As a sort of consolation, Dusty pulled out the 15-footer he’d caught the night before. The snake lay in a bag—I think it was a pillowcase. Dusty pulled it out of a compartment attached to the side of his truck. I expected him to flop the thing out onto the ground the way you would a sack of trash, but he was very gentle.

The snake was out and seemed to know it should escape, but it didn’t move with great desperation. She was beautiful. There was a hidden symmetry to the skin that my mind couldn’t quite figure out. Dusty told me to grab the snake by the back of the head, but not to grip her to death. He draped the snake over my shoulders. She was heavy and felt waxy and cool in my hands like she was impervious to the humidity. She was docile. Like she had given up, knew her fate and was at peace with that.

The author with a captured snake.

Image: Courtesy Photo

Dusty took pictures of me to show my friends.

The Florida we are trying to preserve is the Florida that serves us. I wondered what made me any more Floridian than this snake in my arms. Because I was born here? I thought about oranges. They aren’t from here, either. The Spanish brought them here from Europe, and the Portuguese brought them there from China 500 years ago. Now they’re on our license plates.

We brought her here and now we are trying to get rid of her. She’s just doing the only thing she knows how. It crossed my mind that I should let her go.

Excerpted from “Feast of Pythons (Homage to Harry Crews)” by Isaac Eger from The Wilder Heart of Florida: More Writers Inspired by Florida Nature, edited by Jack E. Davis and Leslie K. Poole. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2021. Reprinted with permission.