Mountains of the Mind: Scholars’ Rocks from China and Beyond

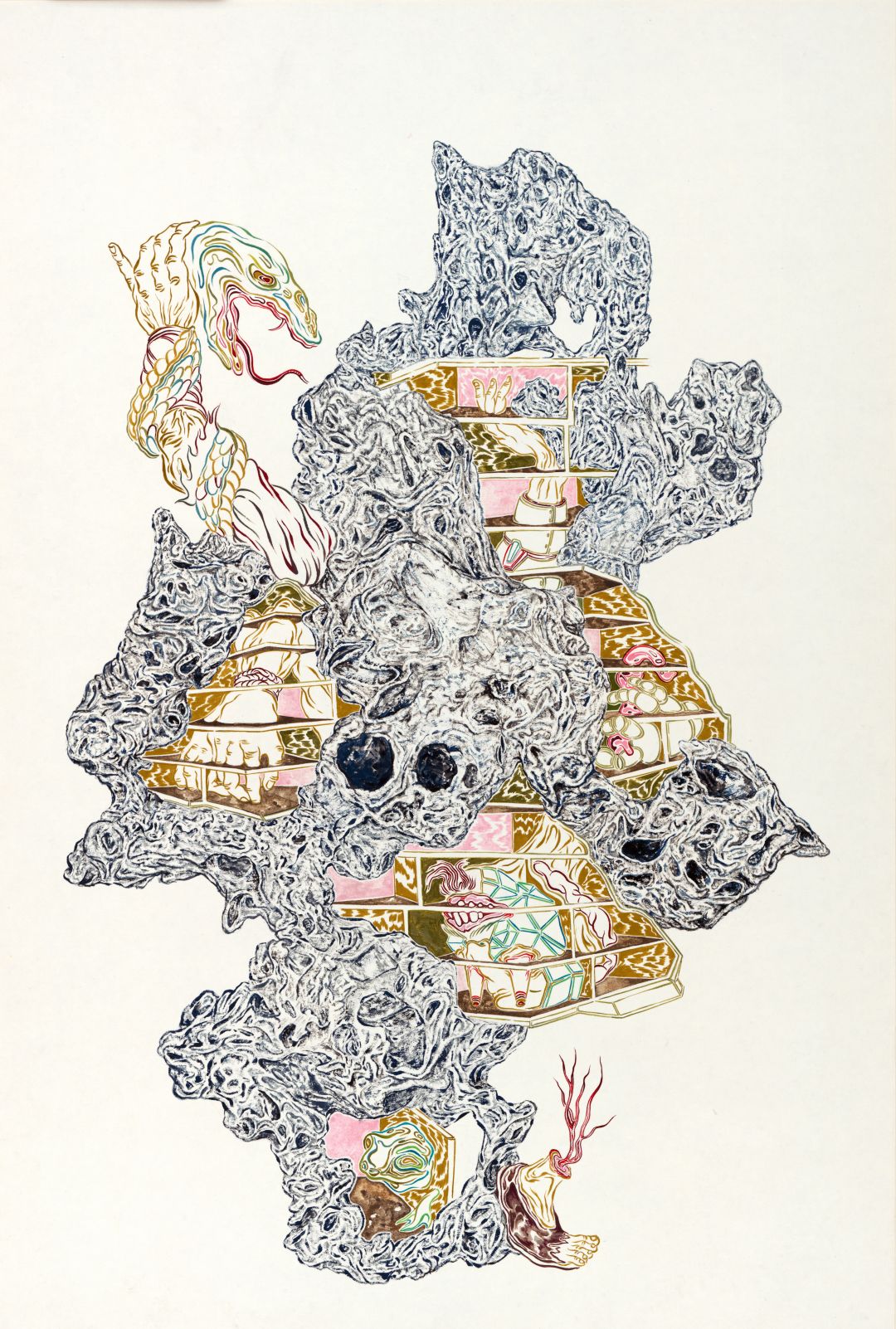

Howie Tsui (Canadian, born in Hong Kong, 1978), Avatars of Entombment #1 (Calcify), 2021. Paint and ink on mulberry paper mounted on silk. Museum purchase with funds given by Lucia and Steven Almquist. © Howie Tsui, 2021

Curious rocks have been venerated in China since ancient times. Wealthy elites of the Tang dynasty (618–907) sought out magnificent limestone boulders for their gardens. During the Song dynasty (960–1279), scholars began collecting smaller rocks with sculptural shapes, interesting surface textures, and striking colors. These became known as gonshi, meaning “spirit stones.” Because of their association with literati culture across East Asia, they are called “scholars’ rocks” in English.

Suitable stones are harvested from lakes, riverbeds, mountains, and other remote locations, where they have been sculpted by the elements over millions of years. In the process of becoming scholars’ rocks, they may be cut from bedrock, trimmed, carved, polished, inscribed, and finally mounted in a custom-made stand at an angle that enhances their visual appeal. As such, scholars’ rocks are both natural objects and products of human creativity.

Yellow Taihu Stone, 13 × 14 3/16 × 8 11/16 in. (33 × 36 × 22 cm), Gift of Stan and Nancy Kaplan, 2019, SN11681.63

Historically, connoisseurs displayed their stones in their studios alongside paintings, antique inkstones, archaic bronzes, and other treasures. They were admired for their abstract sculptural qualities, or alternatively, for their resemblance to human figures, animals, trees, or coiling clouds.

Stones that suggest mountains peaks and powerful natural forces are especially revered among East Asian petraphiles. As objects of imaginative contemplation, these landscapes in miniature invite the mind to wander. For Daoists, mountains are the meeting place between heaven and earth. Ascending them brings one closer to the gods, while concealed beneath are great subterranean caverns inhabited by immortals. Even a small desktop rock could be a portal to another realm.

Paintings of remarkable stones produced from the eighth century to the present reflect and reinforce the significance of rocks in East Asian culture. Their fantastic shapes invite the brush to play, and a skillful artist can animate their subjects or lend them magical qualities, such as the ability to shapeshift or generate their own weather.

White Taihu Stone, 21 1/16 × 9 7/16 × 7 1/2 in. (53.5 × 24 × 19 cm), Gift of Stan and Nancy Kaplan, 2019, SN11681.41

Petraphila is by no means unique to China, but the rich culture of appreciating scholars’ rocks that developed there has diffused across East Asia and beyond. As well as objects from China, this exhibition includes objects from Japan, Korea, Canada, and Italy. On view for the first time at The Ringling are scholars’ rocks recently donated from the extensive collection of Nancy and Stan Kaplan. These are joined by works on paper, including a group of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Chinese and Korean paintings loaned from the Dongguan Lou Collection. We also are delighted to share new acquisitions, Avatars of Entombment #1 (Calcify) and Avatars of Entombment #2 (Calcify), and Avatars of Entombment #2 (Offering), by Howie Tsui (Canadian, born in Hong Kong 1978), which employ the classical motif of the scholars’ rock to comment on contemporary social, political, and personal concerns. Tsui’s paintings generously funded by longtime Ringling supporters Lucia and Steven Almquist and the Carpenter Foundation.