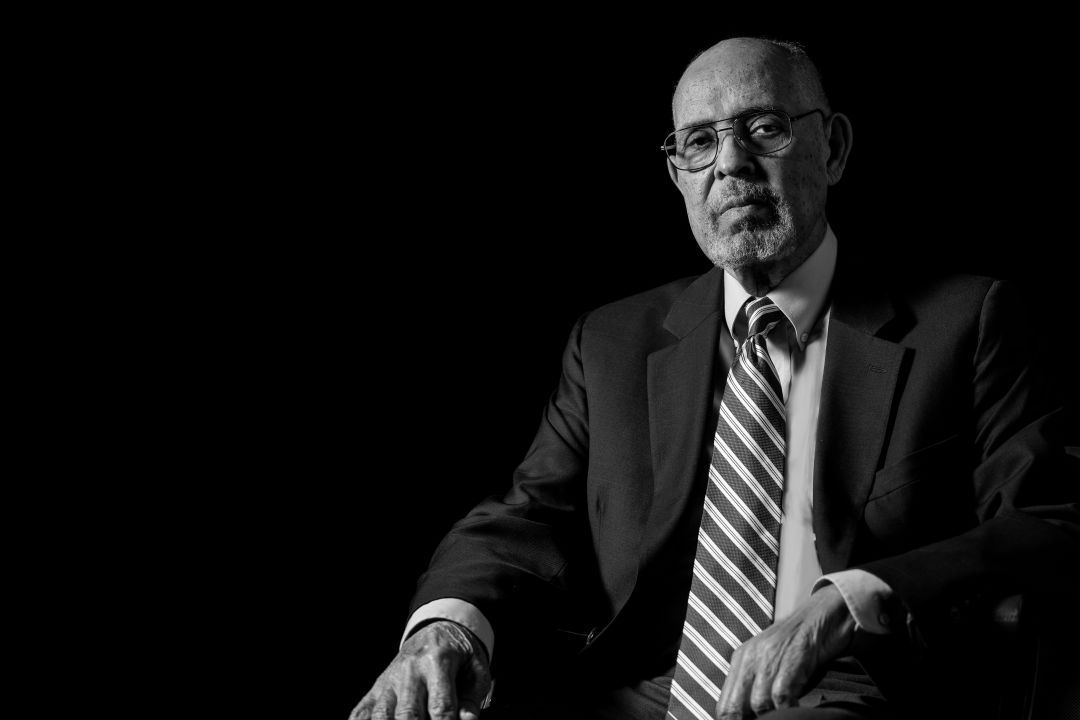

Late U.S. Ambassador James A. Joseph Fought for Equality His Whole Life

This article is part of the series In Their Own Words, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

Ambassador James A. Joseph on stage at the Historic Asolo Theatre at the Ringling Museum.

Image: Michael Kinsey

Editor's note: Amb. Joseph passed away on Feb. 17, 2023.

Born in 1935 in segregated Opelousas, Lousiana—the state headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan—former U.S. Ambassador James A. Joseph has spent his life fighting for equality and social justice. Over the course of his career, Joseph has served as an ordained minister and university chaplain, a civil rights activist, a business leader and an adviser to four American presidents. He’s also a graduate of Yale Divinity School, a philanthropist, professor and author and the former ambassador to South Africa, a role in which he worked closely with the late Nelson Mandela.

In recognition of his work, in 1999 Joseph was inducted into South Africa’s Order of Good Hope, the highest honor bestowed upon a citizen of another country. In 2008, he was elected to the Louisiana Political Hall of Fame. His undergraduate alma mater, Southern University, has named an endowed chair after him, and the Association of Black Foundation Executives established the annual James A. Joseph Lecture on Philanthropy in his honor. In 2010, the United States Peace Corps paid tribute to Joseph for his lifelong contributions to voluntarism and civil society, and he is the recipient of 19 honorary degrees.

In 1979, Ebony magazine named Joseph to its list of “100 Most Influential Black Americans,” and later, Fortune magazine named him one of “America’s Best Nonprofit Managers.” In 2014, Joseph received Yale Divinity School's Lux et Veritas award, which honors distinguished graduates.

Now 85, Joseph lives in Sarasota with his wife, Emmy Award-winning journalist Mary Braxton-Joseph.

What was it like growing up in the South?

"I attended school in a dilapidated building that was ruled unfit for white students and studied from books that were deemed unsuitable for white students. But none of that deterred the good teachers who cared about us.

"Opelousas [my hometown] was the state headquarters of the KKK—lynchings were a common occurrence. We could get attacked by white high school students simply by walking home; in fact, a close friend was killed this way. One day after school, my brother and I were chased by some white boys. We ran up to the first home we came to and hastily knocked on the door. It belonged to a white family who allowed us to shelter inside. They called our father, who came to pick us up, gun in hand. When he arrived, the boys were still waiting outside.

"The KKK was always present in our town, whether riding through the streets or holding parades. They made regular threats to those who tried to change the status quo. Those people were considered 'uppity,' and if you were labeled that, you would get a personal visit from the Klan."

Tell us about your career.

"I received a master’s degree from Yale University Divinity School and taught at Stillman College in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, where, in 1963, I took a leadership role in the local civil rights movement. In 1971, I helped to form the Association of Black Foundation Executives, which is still thriving today. I became vice-president of Cummins Engine Company, and from 1982 to 1996 served as president and CEO of the Council on Foundations, an international organization of foundations and corporate giving programs, which changed communities and lives on five continents."

What about your government service?

"I served as Under Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior for President Jimmy Carter. President Bill Clinton asked me to be founding chair for the Commission on National and Community Services, which developed AmeriCorps. I also served as vice chair of the nonprofit Children’s Defense Fund. In 1995, President Clinton appointed me as U.S. ambassador to South Africa, where I worked with the late President Nelson Mandela to build a new democracy.

"Later, I founded the United States-Southern Africa Center for Leadership and Public Values, a joint endeavor between Duke University and the University of Cape Town. Since its inception, more than 200 graduates, such as former Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter and current Archbishop of Cape Town Thabo Makgoba, have advanced in significant leadership roles. Closer to home and after Hurricane Katrina, I was asked by the governor of Louisiana to chair the Louisiana Disaster Recovery Foundation, now the Foundation for Louisiana."

You were a civil rights organizer and leader in 1960s. How does our current climate of protest compare?

"My career launched in 1963 after I graduated from Yale Divinity School. That time period was described by social critics and the press as the “revolution of the underclass.” Now, it is a counter-revolution fueled and financed largely by the 'upper class.''

"Back then, I had just moved to Tuscaloosa, Alabama, which was the national headquarters of the KKK. I collaborated with three local ministers to organize a group when Martin Luther King Jr. came to speak. His visit brought new participation and energy. The audience was so large that we had to set up speakers outside—that’s when we launched the Tuscaloosa Citizen’s Action Committee.

"We became a full-fledged movement when a couple hundred college students and members of our respective congregations marched to the new Tuscaloosa County courthouse to read a statement demanding they remove the “colored” and “whites” segregation signs. When we turned the corner, not only did we find the police, but the KKK and the infamous “Bull” Connor [commissioner of public safety for Birmingham] with his “storm troopers” as well. We had a mission to make it to the courthouse steps, and we did, but I didn’t get to read the statement. I cannot recall if the KKK pushed us into the police, or the police pushed us into the Klan. All I can remember is that baseball bats were swinging, and I was struck a number of times.

"The press was there that day, and the story got picked up. The community and media became aware of our existence and, as a group, we became more sophisticated. I was amazed at how many people responded to our invitation because so many were afraid of the Klan.

Did you think about the danger back then?

"In many ways that experience was overwhelming, but we did not have fear. If I was doing this now, I’d think of all the reasons not to, but I decided to go south after college. Like so many others, I needed to make a contribution. Remember that 1963 was the year that Gov. George Wallace stood in the doorway of the University of Alabama to block two Black students from registering. It was the year of the March on Washington, the Birmingham Church bombing and the assassination of civil rights activist Medgar Evers. It motivated us. There were times that I was trailed, and the police chief said my life was in danger. I should have given it more thought because I had a new baby. Almost every night I would receive intimidation phone calls from the Klan."

Do you draw any parallels between South Africa and apartheid and racism in America?

"I grew up knowing that I was existentially part of two great movements—civil rights in the U.S. and human rights in Southern Africa. The latter caught my attention in 1956, early on in my college senior year, when I saw how the South African Women’s March surrounded the Union Buildings and made demands of the apartheid government. I realized then that I wanted to do something about both.

"Issues that South Africa dealt with then, which we are looking at today, were the signs and symbols of an apartheid era—whether the names of oppressive people and organizations ought to be retained, as well as the debate about reparations. Black leaders decided they would not push for reparations, but instead opted to reconcile conflicting images of the past and the alienation between culture groups.

What are your thoughts on re"parations?

"While working with President Mandela, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and others on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, I learned about the role of the narrative during a cultural movement. For example, while I support the notion of reparations, the term has become distorted. I prefer the phrase “economic reconciliation” instead—it opens the door to a discussion.

"What we need is a national public policy to create economic development. Years of intentional underdevelopment, such as segregated schools, redlining and job discrimination, have been backed by public policy. Whether they are called reparations or social programs, I would start off with a major national fund intended for the development of Black communities, which should be led by both policy makers and people in the community."

President Nelson Mandela, Mary Braxton-Joseph, and Ambassador James A. Joseph in February 1996.

Image: Courtesy Photo

What was it like meeting President Nelson Mandela when you were a U.S. ambassador?

"This was an important and memorable occasion for me, considering I had spent much of my adult life as an activist seeking freedom for Mandela, and urging the creation of a multiracial democracy in South Africa.

"Two striking moments come to mind. In 1976, the South African government refused to give me a visa because I funded the documentary Last Grave at Dimbaza, which was shot clandestinely and smuggled out of the country. It had an enormous global impact because it displayed the shocking inequities between Blacks and whites. Two decades later, I arrived at the Jan Smuts International Airport (now the OR Tambo International Airport) as the U.S. Ambassador. When I set foot on South African ground, I reflected on the change that had occurred from being denied a visa to now being charged with a directive from President Clinton: do whatever I could to help President Mandala build a new democracy.

"Presenting my credentials had all the wonderful pomp and circumstance trappings one would imagine. I made a short speech, extended greetings from President Clinton, and Mandela responded with brief remarks. Afterwards, he was warm and personal, and invited my wife, Mary Braxton-Joseph, and me to his office for tea. While there, we wondered how to ask for a photograph to mark the occasion. Not long after, we were delighted when Mandela said, 'Mr. Ambassador, would you do the president of South Africa the honor of having his photo taken with you?' I smile thinking of this moment, which was a demonstration of Mandela’s humility and charm."

What are your thoughts while watching all these new protests unfolding?

"Today we are witnessing a multiracial coalition. We had it in the ’60s, but not as pronounced. Take a look at Black Lives Matter; it’s a concept that’s broader than just an organization. Also, we had a group of high-profile national leaders such as activist Julian Bond, the head of the NAACP Roy Wilkins, and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s [Rep.] John Lewis. Today, those being recognized for the work are leaders at local levels, with no one person leading, such as Martin Luther King Jr. Now movements look more like the grassroots organization that I was involved with in Tuscaloosa."

What do you want your white friend, neighbor, colleague or community to be doing right now?

"Well, that is a complex question, so the answer is complex: Do what you can do, wherever you are. Everyone is looking for something dramatic; however, it is important to remember that wherever you are, you can be helpful. Look around you, see what change you can make in your own organization or existing network, from an open conversation about race with a neighbor to policy changes in your community; all will be helpful to the cause of social justice."

What would you say to the next generation of social activists?

"This is your moment. A lot of attention is given to our movement in the ’60s, but those were different times. We accomplished a lot, and we left a lot undone. This is your opportunity to complete the American Revolution."

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill