Educator Teidra Everett on Code-Switching, Tokenism and Creating a Diverse Classroom

This article is part of the series Listening to Diverse Voices, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

Teidra Everett

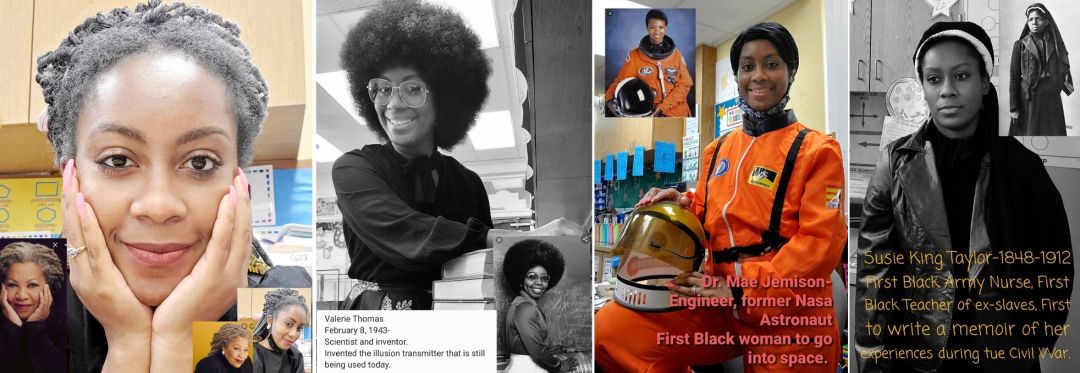

Image: Michael Kinsey

Teidra Everett has dedicated herself to education for more than a decade. A second-grade teacher at Bay Haven School of Basics Plus, Everett is known for creating a classroom that feels more like a community. And for the past four years, she has become known as the woman who brings Black History Month to life, modeling herself after different Black historical figures every day of February—from lesser-known changemakers like Valerie Thomas, Susie Taylor King and Mae Jemison to household names like Serena Williams, Maya Angelou and Shirley Chisholm. “The central message is for kids to not stop dreaming, and to learn from the struggles from the past,” she says.

In addition to her work in the classroom, Everett—who was previously a juvenile probation case manager with The Henry & Rilla White Youth Foundation in Tallahassee—works as a co-facilitator for the SRQ Strong: Raising Anti-Racist Children parenting workshop and as a mentor for the J5 Mentoring Group. She and her husband Jeremy have three children.

You grew up in Jacksonville. Tell us what that was like.

“I grew up in a single-family home and did not meet my father until I was nine years old. When I was young, I was shielded from racism until it happened—and it came from my third-grade teacher in the ‘90s, who said that I was ‘showing my true colors.’ In that moment, I didn’t understand what she meant. When I got home, my mom—who grew up in 1950s—explained that she was calling me a Black kid who acts differently from the other students. I couldn’t look at my teacher the same way after that. Until that point, I was a good student and had been told that I was a great kid. But her mixed message told me that I was now a bad kid because of the color of my skin.

“Before that incident, I was the token Black child. I was articulate and not a troublemaker. I was given opportunities such as being the only student allowed to spend time with my white teacher and her daughter on weekends. I was also chosen first for various activities.

What were middle and high school like for you?

“While in middle school, I moved to Palatka, Florida—a small town where my father grew up—where the lines of white vs. Black were clear.

“I was the first Black girl on the cheerleading squad. That was a mixed message in many ways. First, I wasn’t that great to be able to make the team, so tokenism felt real there, too. Then the Black kids didn’t like me because I made the squad and would say things like, ‘You think you’re all that because you made cheerleading.’ I was also told that, because of these activities and privileges, that I ‘wasn’t Black enough.’

“My mother instilled in me to be pro-Black, and to work hard to always stay five to 10 steps ahead because I am Black. I saw her struggle because she would have to take uncomfortable actions with white people in order to make ends meet. It’s called code-switching—in the culture, there’s the professional version of you and the version of you who has a comfortable group of friends who see you as you are. I had to find where I fit in the mix. And in a small town with racism, how was I going to get ahead?”

How did this affect you?

“For a while, I didn’t wear my hair a certain way so that I wouldn’t seem too ethnic. The first time that I wore natural hair, I was teaching at Emma E. Booker Elementary School and I had natural locks. I was uncomfortable even then, but I figured that at that point, if people didn’t want me as I was at 31 years old, then that was about them.

“I attended Florida A&M University, a historically Black college and university, where all professors are pro-Black thinking—meaning, they reminded us to never forget who we are. They instilled in us a clear vision of what goes on in the world with regard to the Black community, such as having an understanding of who is getting jobs and who is not, and how we have to decide how to make that work for us.

“But it was difficult growing up working to find who I truly was and where I fit in the mix of all that.”

Nearly 150,000 children in Florida have contracted Covid-19. As an educator, do you see racial disparities in that number?

“The disparities actually have the same correlation between adult and child. The populations that are most affected are minority and economically challenged groups. If these groups are not provided with needed healthcare and have pre-existing conditions, they naturally seem to possess a weaker immunity to viruses. But I’m not sure what could be done to change these statistics.”

Some educational experts say that pandemic learning pods could benefit marginalized students. What are they, and what are your thoughts?

“I think learning pods are a great idea for stay-at-home families with older children. I don’t think primary learners benefit a great deal. Although kids are able to have social interactions with each other, these are ‘hand-picked’ groups of children who are typically alike in disciplines and economic status; for example, six kids from the same neighborhood. This puts them at a disadvantage for social success when they are reintroduced to children who were outside of their learning pod.”

What advice do you have for how to approach a conversation with a child who has been called a racial slur?

“First, it’s important to build the child’s self-esteem. Ask if they feel that they are the term they were called. Usually, the answer is no.

“Second, ask if they identify with the word—for example, ‘Does this make you feel negative, sad, or otherwise?’ Then discuss how it’s not OK to name-call or to be racially profiled. It’s also important to ask if the child still want to be friends with the person who did it.

“When it comes to the n-word, I suggest breaking it down historically and explaining that it’s a word that means ‘less than’ and ‘not smart.’ Then ask the same questions above. ‘Do you feel like you’re a person who can’t think for yourself?’ If the answer is no, then impress upon the child that they don’t identify with the derogatory term and that, as uncomfortable as it is, it’s important to tell the person who used it that they can’t speak to you that way and you will not accept it.

“Lastly, once you break down a word or term, sometimes the child will respond that they do feel the way the term was intended. So go back to step one to build up their self-confidence. For example, if the child says that sometimes they don’t feel smart, ask, ‘Why is that?’ They may respond, ‘I didn’t do good on a test.’ Your response could be, ‘Well, that’s one test, that’s not you.’ Sometimes the child may identify with a phrase, and it's up to the adult to explain why it’s not who the child is.”

How do you create an engaging classroom that’s focused on cultural diversity and social justice?

“I begin the school year by explaining how we are family inside our classroom—they are all cousins, and I am the aunt that they will learn from. I tell them that I should never hear about a conflict within the class, because they know to look out for each other and to use kind words to resolve issues. Nothing less is acceptable.

“I have witnessed the effectiveness of that initial introduction. The kids—approximately half are minorities—are kind, responsible, and actively listen and work well together, even when they partner. And they enjoy learning from each other, especially when they share personal life stories. It is a community within a community.”

A few of the history makers Everett dresses up as for Black History Month.

Image: Courtesy Photos

You’re well-known for dressing up as Black history makers during Black History Month. Tell us about that.

“For the last four years, I’ve been creating this experience for my students. There are quite a few amazing trailblazers who are far less glorified than others—and there aren’t enough days in February to honor them all. Here are four examples:

“Harriet Powers (1837-1910) was a folk artist and quilt maker who used her talents to record legends, Bible stories and events. This was impactful because not many events were documented during that time period.

“Valerie Thomas (1943-present) is a scientist and inventor. She invented the illusion transmitter that allows a normally flat image to appear in 3D. It is still in use by NASA.

“Alice Coachman (1923-2014) was the first Black woman to represent the USA and win an Olympic gold medal for the high jump in 1948.

“There are also women like Dr. Renee Gordon (1984-present), a Florida A&M University alum, who is a scientist and researcher spearheading STEM programs in Tallahassee.

“Most students at the primary level are visual learners, so what better way to teach them—and some adults—than by making history come to life?”

How do you think we can improve race relations?

“Be open-minded, have compassion for those who are not like you, and without assuming, ask questions—even when they are uncomfortable. You will be surprised by the responses.

“Now, some Black people are tired of being asked the questions that could be researched on your own. I’m not there, yet—not to say I won’t be at some point. But what everyone should know is that Black people are a most accepting community. This has a lot to do with the Black church—forgiveness is ingrained in us. We learn that if we don’t forgive, we will not elevate ourselves.”

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill