Pioneering Physician Randall C. Morgan Jr. on His Lifetime of Fighting for Health Care Equity

This article is part of the series In Their Own Words, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

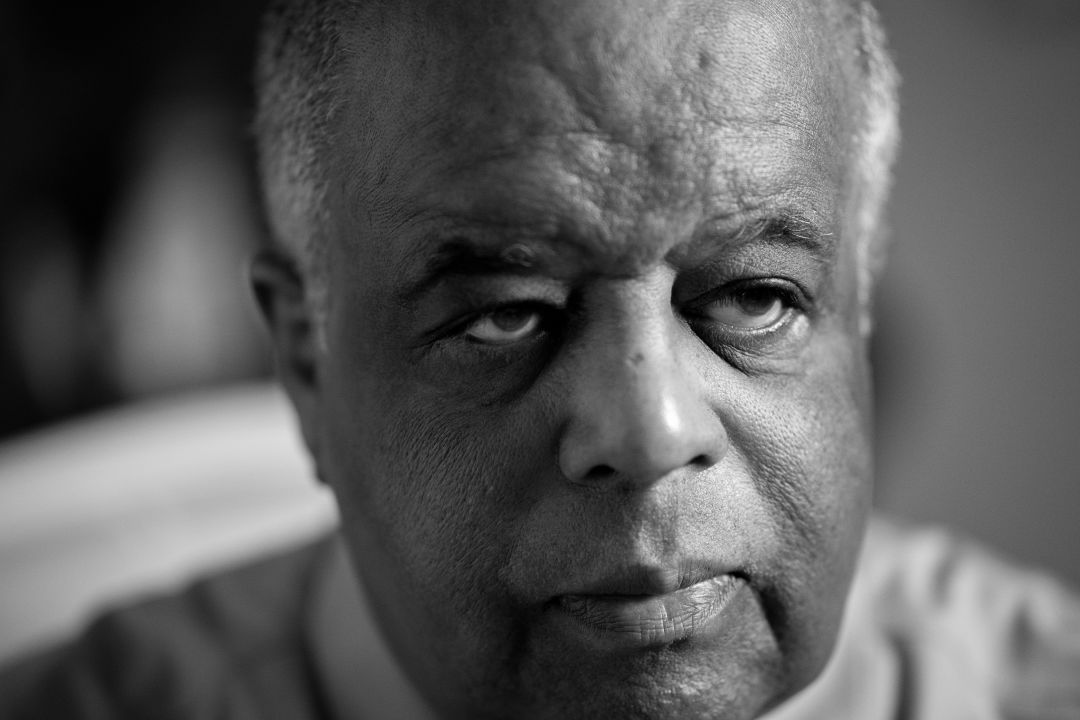

Dr. Randall C. Morgan Jr.

Image: Michael Kinsey

Dr. Randall C. Morgan Jr. has been on the frontlines of the fight for medical equality for all for 46 years. A practicing non-surgical orthopedic doctor and CEO of the W. Montague Cobb/National Medical Association Health Institute—which is committed to finding solutions for racial and ethnic disparities in health care—Morgan grew up in the steel-manufacturing town of Gary, Indiana. He was the only Black student in his graduating class at Grinnell College, received his medical degree from Howard University College of Medicine, and completed his doctoral residency at Northwestern University, where he was the first Black chief resident.

Morgan, now 77, opened a practice in Evanston, Illinois, and worked as a faculty member at Northwestern. After receiving a letter from Richard Hatcher, the first Black mayor of Gary (and only the second Black mayor in the U.S. at the time), asking him to come back due to a shortage of orthopedic surgeons in the area, Morgan and his wife, Karen, returned home, where they remained until relocating to Southwest Florida in 2005. Morgan became the first Black orthopedic surgeon in Sarasota.

Today, in addition to his medical practice and work with the Cobb Institute, Morgan is the executive director of the J. Robert Gladden Orthopedic Society, an organization representing Black orthopedic surgeons in the U.S. He also mentors high school and college students, performs with his band Soul Sensations, and schedules Zoom calls with his three daughters and six grandchildren.

Tell us about your family history. Did your family move to Gary during the Great Migration?

“My father’s family is from Mississippi. There were eight children and one by one, they all migrated north to Chicago, New York and North Carolina.

“In the 1920s, my mother’s family migrated to Chicago, then Gary in the early 1930s. My maternal grandfather, H. Theo Tatum, was from Texas and my grandmother was from New Orleans, where her ancestors were slaves who can be traced back to 1810. My grandfather became a renowned educator and principal for 30 years at Gary Roosevelt High, the historic Black high school. He retired in 1961 after he presented my diploma to me on graduation day.

“Later, my father, who also owned two drugstores, founded the first independent medical center owned by Black physicians in Gary. When I returned to Gary in 1975, we founded the first Black-owned orthopedic group practice, Orthopedic Centers of Northwest Indiana, where I served as president. It became the largest Black-owned orthopedic group in the country, with 11 physicians, including two women. One of the things I’m most proud of is that my grandfather, father and I have been inducted to the Steel City Hall of Fame in Gary.”

What brought you and Karen to Sarasota?

“In 1980, we came to see my favorite baseball team, the Chicago White Sox, during spring training. We stayed at The Colony Beach and Tennis Resort, and immediately decided that it was paradise. In 1985, we purchased a unit there and returned several times every year.

“Over time, I was approached by multiple white guests who asked if I played for the Pittsburgh Pirates. I would play along and reply that I did, saying, ‘I went two for four today.’ I imagine that the white guests could not envision a Black man on Longboat Key dressed in a tennis outfit or evening attire being anything other than a baseball player.

“Another memorable moment was when our group passed a private party at The Colony that was hosted by Pirates star player Bill Madlock. We waved at Madlock, a certain acknowledgment that occurs from one Black person to another in places like that—my wife calls it ‘the nod.’ Not long later, the waiter brought us a fifth of Dom Perignon with his compliments. I tried to figure out where I may have met Madlock, but then I noticed Willie Stargell, a Black Pirates left fielder and Hall of Famer whose party was at the table next to ours. I immediately knew that the Dom was misplaced by the staff, mistaking one Black man for another. So I teased the waiter for his mistake, but we did not return the Champagne!”

Many people are unaware of this kind of subtle discrimination.

“What many white people don’t know is that [Black people] live as ‘double agents’ our entire lives. We flip the switch; it takes so much energy to exist in two or three separate worlds, when I wish I could just relax in one. Black high achievers have to go extra miles and take on multiple identities, which means we have to work harder and smarter to get where we are.

“The most depressing thing for me is that we are right back where we were 50 years ago in terms of the partitioned society. Above all, I wish our cultural diversity in the community would be celebrated and not just tolerated.”

What was it like coming up the ranks as a Black doctor in America?

“It was a challenge. When I was a resident at Northwestern, I encountered patients who were uncomfortable having a Black doctor care for them. Even today, I have to negotiate that. For instance, I have to be careful how I present not-so-great medical news lest I’m perceived as the arrogant, angry Black male.

“The major challenge now is to enhance the training of physicians and staff in the hospital environments to deal with cultural sensitivities. It’s also important to address the diversity, equity and inclusion issues hospitals face as a major health center and employer.

“People are looking for diversity when choosing doctors. We need more skilled Black doctors to become part of this community.”

In 2010, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services made a lofty goal for its Healthy People 2020 plan “to achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups.” How would you score their efforts?

“I would score the efforts a C+, and the accomplishments a D-. Only 4 percent of practicing physicians in the U.S. are Black. And of all practicing orthopedic surgeons, only 1.9 percent are Black. These statistics are in danger of decreasing. Black medical students make up only 4 percent of students, and that has been a flat line since the 1970s.

“I began to understand the breadth and depth of the inequities in health and education when I was with the National Medical Association (NMA) in the mid-1980s. The NMA was founded in 1895 because the American Medical Association refused to accept Black doctors. I was elected national president of the NMA in 1996-1997.

“During my presidency, I was involved with anti-affirmative action cases such as Hopwood v. the State of Texas, which decided that the University of Texas could not use race as a factor in determining which applicants to admit, and the University of California v. Bakke, where the U.S. Supreme Court declared affirmative action was constitutional but invalidated the use of racial quotas.”

What is the difference between health disparities and health inequities?

“Health disparities refer to a higher burden of illness, injury, disability or mortality experienced by one population group relative to another group. The difference between the groups is health coverage, access to care and quality of care. For instance, Black women die of breast cancer in their 30s and 40s at a greater rate than white women.

“The phrase ‘health inequities’ is based upon the fact that everyone does not have an equal chance at good health outcomes. The differences are systematic, such as the distribution of health resources between different population groups arising from social conditions. Equal access to care may require more funding to create equity. If we are going to achieve health equity, we must improve access to care.”

“We have to do better. We have to be more inclusive.”

How is Covid-19 affecting health disparities?

“Covid-19 has pulled the curtains back on the constellation of problems related to health disparities. People with pre-existing conditions like diabetes, hypertension, obesity and heart disease —all common in the Black community—are more vulnerable to Covid-19, and [these conditions] reduce their chances of survival [should they get the virus]. The disease is complicated by the social determinants of health—that is, where people live, work and play.

With regard to the development of vaccines, diversity is crucial for clinical trials.

“At present, Black participants account for just 4 percent to 5 percent of representation in the Covid-19 vaccine clinical trials. Three times that number is needed to understand the effectiveness of a vaccine in Black communities.

“Also important to know is that the standard goal for a vaccine is 30,000 participants for Stage Three trials. Recruiting is still underway, so to think a vaccine will be available before the election is the stupidest thing I have ever heard. You can’t go against science.”

Why are Black participation numbers so low?

“It’s due to lack of consent and respect from the federal government and the medical community, which has created a long history of distrust in the Black community. An example is the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, which ran from 1932-1972 and in which the Black men in the study were told they were being given free health care, but were instead infected with the disease, with no known treatment. In 1997, during my NMA presidency, I attended a ceremony at the White House where President Clinton issued a formal apology to the Tuskegee experiment victims.

“Also, in 1951, a Black woman named Henrietta Lacks, who had cervical cancer, visited Johns Hopkins University for treatment. [She died of the disease in 1951.] Lacks’ unique cancer cells were harvested [by a Johns Hopkins researcher] without her knowledge or consent [because instead] of the cells dying, they would double every 24 hours. They are referred to as HeLa cells and are still used today worldwide to study the effects of drugs, AIDS, gene mapping and viruses on the growth of cancer cells, among others, without the need to experiment on humans. HeLa cells were also crucial to the development of a polio vaccine.”

What do you want your white medical colleagues to be doing right now?

“I want them to figure out ways to make health care accessible to all—whether that’s creating methods to reach a greater percentage of the population, which could mean changes in office locations, or mentoring early-career doctors.

“Be broad in your thinking and involvement. Don’t just do your work, share your skills and talents, and care for the community. There is considerable personal and intellectual wealth in Sarasota, which creates more responsibility for people in this community to give back.”

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill