New Works Highlight the Collection at The Ringling’s Kotler-Coville Glass Pavilion

Curator Marissa Hershon

Image: Courtesy Photo

Over the last decade or so, the popularity of glass as an art form has risen in Sarasota, with exhibitions and galleries devoted to it at the Ringling College of Art and Design, the late-lamented Longboat Key Center for the Arts and other venues. Most prominent in the field, though, is the Kotler-Coville Glass Pavilion that opened at the John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art in 2018.

Established thanks to local Sarasota glass collectors Philip and Nancy Kotler and Warren and Margot Coville, the two-floor gallery space is dedicated to 20th-and 21st-century studio glass by American and international artists using a wide range of aesthetic approaches and differing techniques. Lately, the permanent collection has been bolstered by new acquisitions. We asked Marissa Hershon, Ringling’s curator of Ca’ d’Zan and decorative arts, to walk us through some examples from this visually stunning collection, on view adjacent to the John M. McKay Visitors Pavilion every day the museum is open to the public. Best of all: Admission to The Kotler-Coville Glass Pavilion is totally free, so you can take in its riches even if you don’t have time to enjoy the whole museum. Here’s a curated selection.

Enrico's Walls by Judi Elliott

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Enrico’s Walls, 2018

Judi Elliott

Museum purchase, 2020

Elliott is widely recognized for her innovative work in kiln-formed glass, and Hershon says this piece, from the artist’s latest series, responds to “the built environment of Elliott’s home and studio in Canberra, Australia.” She adds, “Elliott imbues layers of meaning in her strikingly abstract geometric compositions. Incorporating concepts from Jungian psychology, the bright and colorful front of Enrico’s Walls symbolizes the building’s persona, whereas the contrasting black and blue composition on the back signifies the psychological concept of the shadow, one’s hidden side that is unconsciously expressed in dreams.”

Yellow Heart Amulet Basket by Laura Donefer

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Yellow Heart Amulet Basket, 2012

Laura Donefer

Gift of Warren and Margot Coville, 2020

Hershon calls this piece “a stunning work of art, featuring richly layered glass beads and rods created with a flameworking torch and assembled in a blown-glass vessel.” Donefer has been creating amulet baskets since 2001, when, in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, she was inspired to create containers holding amulets within as “her artistic vision for joy, love, peace and hope.” This particular piece has additional symbolic meaning derived from the artist’s father’s discovery of relatives who perished in the Holocaust.

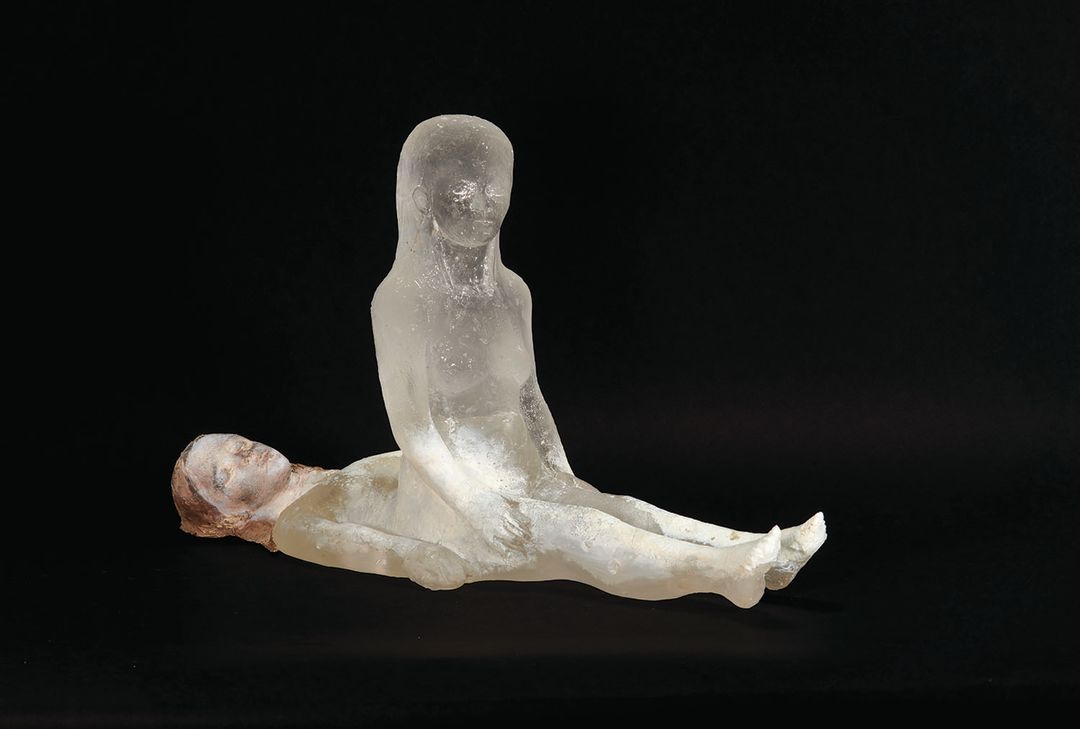

Sleep by Christina Bothwell

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Sleep, c. 2008

Christina Bothwell

Gift of Philip and Nancy Kotler, 2020

Pennsylvania-based artist Bothwell “often explores narrative themes about birth, death and spiritual renewal in figurative sculpture combining kiln-cast glass with raku-fired clay,” Hershon explains. In Sleep, “The soul of a woman, represented in translucent glass, rises from her sleeping form, with the head and feet made of raku-fired clay.” The Sleep series was inspired by the artist’s experience with sleep deprivation while pregnant.

Vase by Richard Marquis

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Vase, c. 1998

Richard Marquis

Gift of Warren and Margot Coville, 2020

Marquis is a West Coast artist who’s made an indelible mark on the American Studio Glass Movement. He first went to Venice to work in the famous Venini glass factory on Murano, mastering the Venetian glass-working technique of making murine, whereby cross-sections of glass canes are joined together to create distinctive patterns on the surface of vessels. He’s known for his experiments with color, and Hershon says, for “adapting traditional techniques that reference kitschy American consumer culture.”

Torso by Martin Blank

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Torso, c. 1998

Martin Blank

Gift of Philip and Nancy Kotler, 2012

Seattle-based artist Blank worked on Dale Chihuly’s glassblowing team before devoting himself to his own studio practice. The Ringling’s example “is indicative of Blank’s fluid aesthetic in defining the musculature of a male torso,” says Hershon. “Blank is inspired by sculptural traditions dating to Roman and Greek antiquity as well as Renaissance masters, yet he works intuitively rather than striving for perfection in the human form. Creating Torso involved layering masses of molten glass and shaping each addition into the form of a figure with a variety of steel tools while continuously reheating the work to keep the glass in a pliable state.”

Untitled by Emma Varga

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Untitled, 2009

Emma Varga

Gift of Warren and Margot Coville, 2020

Hershon says that Yugoslavian-born Varga’s aesthetic evolved in response to her environmental surroundings, especially after moving to Australia from Europe in 1994. There “she developed a fusing and casting technique that created three-dimensional colored patterns,” Hershon explains. “By stacking and encasing colorful sheets of minute fused segments within clear colorless glass, Varga grafts internal patterns that appear to be floating inside the rounded, cubic form.” This cast glass piece was inspired by the small, rounded green hills Varga remembered from a visit to New Zealand.

Rose Dress by Karen LaMonte

Image: Gabriel Urbanek

Rose Dress, 2002

Karen LaMonte

Gift of Philip and Nancy Kotler, 2020

LaMonte’s life-size, cast glass sculptures of dresses “subvert the long tradition of the female nude,” says Hershon, by “concentrating instead on clothing with the wearer absent.” With close looking, however, “The viewer may discern the sculpted form of the female body subtly visible within the clear, colorless drapery.” Hershon says it’s a “technical triumph in casting glass on a large scale. The annealing, or controlled cooling in a kiln, of the three parts forming this sculpture took months before the work could be safely removed from unique molds so that LaMonte could complete cold-work techniques of sandblasting and acid-etching to create the translucent surface finish.”

Moon Bottle II by John Lewis

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Moon Bottle II, 1975

John Lewis

Gift of Warren and Margot Coville, 2015

Lewis established a glass studio in Oakland, California, in 1969, an exciting period of experimentation as the burgeoning American Studio Glass Movement led to the establishment of programs at universities. In the 1960s and 1970s, Lewis created a series of spherical vessels depicting landscapes with moons, clouds and waves. Hershon says that as Lewis worked on the Glass Moon Bottle Series, “He developed an array of imagined geological environments. The artist likens the creative process of making each unique landscape design to painting with molten glass.”

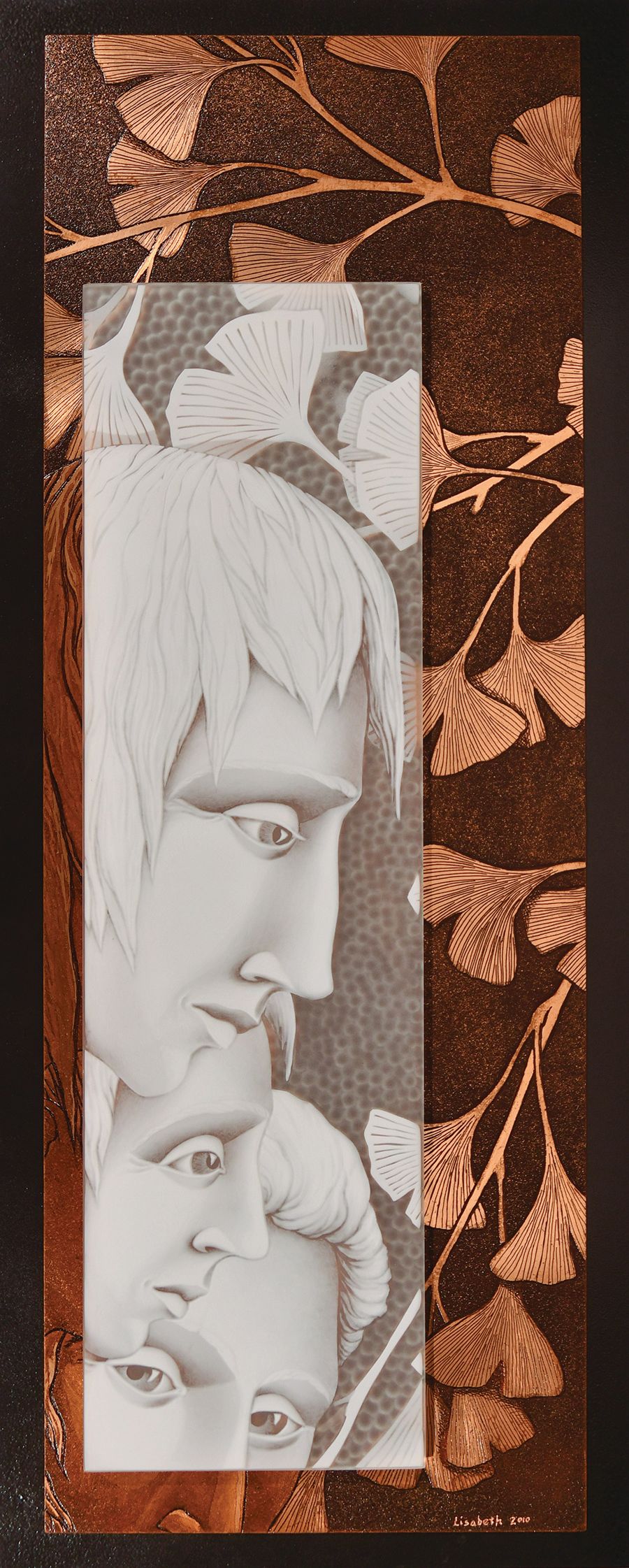

Losing Focus by Lisabeth Sterling

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Losing Focus, 2010

Lisabeth Sterling

Gift of Marian S. Kessler, 2018

Sterling is one of a relatively small number of artists working in the challenging technique of cameo glass, which dates back to ancient Roman glassmaking, with revived interest in the cold-working technique in different periods including French Art Nouveau. “Sterling creates low-relief imagery by removing portions of the top layer of opaque white glass to reveal contrasting colored glass underneath,” Hershon explains. “Much of her work features enigmatic imagery, but Losing Focus portrays a personal narrative,” with the faces representing the artist and her sisters surrounded by gingko leaves.

Luceano Fever by Danny Perkins

Image: Courtesy The Ringling

Luceano Fever, 2000

Danny Perkins

Gift of Philip and Nancy Kotler, 2012

The strong colors and tapering form of Luceano Fever are characteristic of Danny Perkins’ repertoire in glass, according to Hershon. Rooted in the materiality of glass, the work is composed of mold-blown glass fractured into shards and reassembled into a vertical, stalk-like sculptural form. The artist also airbrushes additional color pigments and sandblasts the glass to create a matte surface finish. “Each work expresses different emotions in correlation to his personal relationship with people, nature and contemporary life,” Hershon explains. The work may elicit a range of emotional responses from the viewer depending on the work’s interaction with natural light throughout different times of the day.