Abstract Expressionist David Budd’s Exhibit Opens at the IceHouse

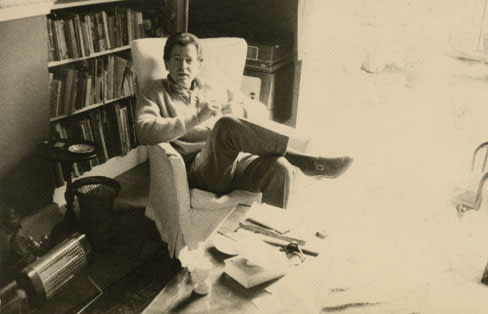

Even those with a fleeting knowledge of art history know the names of superstar Abstract Expressionists Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline. But they may not be familiar with David Budd, an artist and contemporary of those painters, who worked—and played, including spending lengthy sessions at Greenwich Village's famed Cedar Street Tavern—with those giants of the 20th-century art world.

A show opening this month at the IceHouse on 10th Street aims to rectify that situation somewhat, capturing the paintings and personality of this "lost" Abstract Expressionist with Sarasota ties. The show, on view April 4-13, features 35-40 of the late artist's works, many of which have never been seen here before.

"It includes pieces of his from the 1950s through the 1980s," says curator Kevin Dean, who has previously highlighted Budd's paintings in two shows at Selby Gallery on the Ringling College campus. Those who do know Budd's style tend to remember his large, monochromatic canvases, which were thickly textured, with a palette knife swirling paint from left to right, top to bottom. If lighted properly, Dean says, the paintings look almost sculpted, with an aura of "light shining off the water. Some people at the earlier shows saw a connection to Monet."

If Budd was intrigued by the water, he came by it from an early age. Born in St. Petersburg in 1927 and growing up surrounded by bays and bayous, he studied architecture at the University of Florida before switching to interior design in the late 1940s at the Ringling School of Art and Design. After seeing Hans Namuth's 1950 film of Jackson Pollock at work on his "drip" paintings, however, Budd shifted his talents to painting, first here in Florida and then in New York with his first wife, Corcaita "Corky" Cristiani, an equestrian ballerina who performed in the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Budd traveled with the circus for a time, too, working concessions to supplement his income and gathering shaggy-dog tales of life on the road.

When the couple moved to New York City in 1952, he continued to develop his thick-surfaced monochromatic style, eventually having solo exhibitions at the Betty Parsons Gallery there and at Signa Gallery in the Hamptons. Around 1960, with his marriage failing, he moved to France and spent much of the decade there, exhibiting at the Galerie Stadler and even collaborating on a series of drawings with the writer Williams S. Burroughs (who dedicated his 1970 book, The Last Words of Dutch Schultz) to Budd.

The ever-changing tide in the art world had moved to Pop Art in the '60s, and by the time Budd returned to New York in the '70s, he may have felt like a man without a movement. He still managed to exhibit, as well as teach at the School of Visual Arts, and he received several awards, including a Peggy Guggenheim. But, as artist Michael Solomon (who first met Budd as a child) said in an earlier Sarasota Magazine article, "There was some bitterness on his part on seeing artists he felt copied him get more recognition. And, after coming back from Europe, he also felt disenfranchised in the United States in many ways."

At the same time, though, Solomon said, "David always had style," frequently wearing light-colored clothes and a Panama hat, displaying refined manners and the ability to attract beautiful, intelligent women. And he somehow combined both "a sense of the spiritual," added Solomon, with a streetwise attitude that often served him well in New York City.

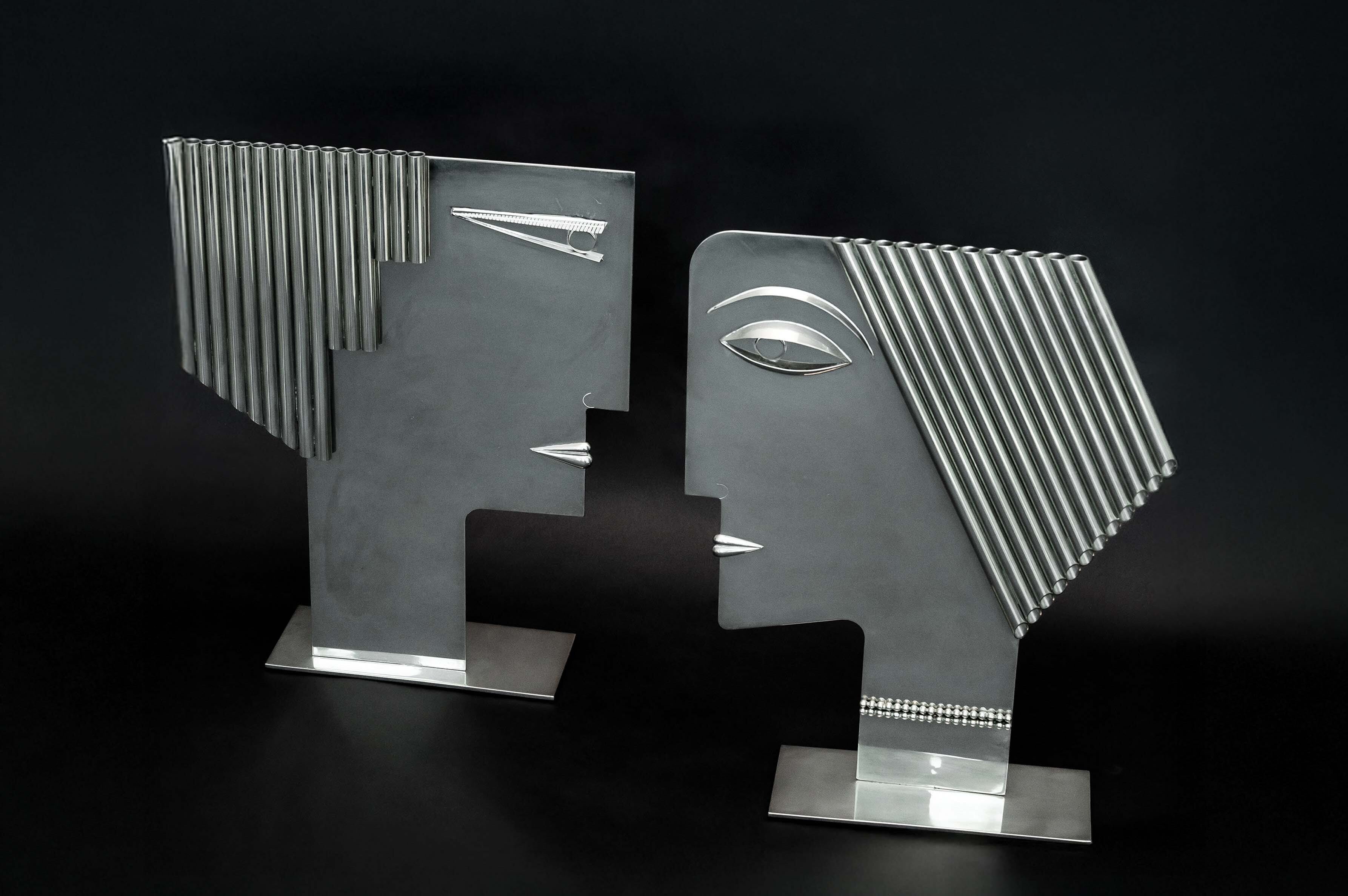

Severe health problems played an increasing role in Budd's life the 1970s and '80s, so much so that he moved back to Sarasota, where his daughter, April, ex-wife Corky, and friend, the late sculptor John Chamberlain, lived, for emotional and physical support. He continued to paint, often on smaller canvases, and viewers will see some of those later works in the IceHouse show as well.

After Budd died, in 1991, many of his works were in storage while the family tried to determine how best to deal with them. Eventually, they gave most of the collection—172 pieces in all—to the Ringling College, Budd's alma mater. Work continues on cleaning and restoring pieces in need of that, and the school has sold a few to collectors (some of whom in turn have donated them to museum collections). And Dean and the college are also seeking museum exhibitions.

"His art is already in a number of museums, including the Corcoran, the High in Atlanta, the Metropolitan and the Guggenheim," Dean says. "So we're reaching out to as many as we can. We're protecting his legacy."

For more details on the David Budd exhibition, go to icehouseon10th.com.