Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author Jack E. Davis on the Gulf of Mexico, History and Hope

Editor's note: This article originally appeared in the December 2018 issue of Sarasota Magazine.

It feels like 100 degrees and it’s not yet 10 in the morning. Without a cloud to hide behind, Jack E. Davis is wearing a black shirt, brown pants and no hat, his freckled scalp left to simmer in the sun. He never once complains about the heat—a Florida boy through and through. We’re on Cedar Key, a barrier island three miles from the mainland, about an hour west of Gainesville. The island city is a vestige of Old Florida, where some parts are only accessible by boat and generations of fishermen still ply their trade. The key is also the subject of the final chapter of Davis’s 2018 Pulitzer Prize-winning history, The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea, a book The New York Times called “a beautiful homage to a neglected sea.”

Davis is bringing me here because this place gives him hope, a necessary coda to his heartbreaking history of the Gulf of Mexico. Davis writes of the Gulf’s once Eden-like abundance—the waters brimming with fish and the sky full of birds—a world so teeming with life that it seemed inexhaustible and eternal. Of course, every story needs conflict, and there is no lack of strife in The Gulf. Davis writes in excruciating detail how each provision of the Gulf’s bounty was met with the insatiability of human greed, so a hopeful end was a necessity, and he wants me to see it for myself.

Image: Fred Lopez

“Even though I’m a historian,” Davis says, “people always ask me about the future. They want to know what’s going to happen. I preach the gospel of the living shoreline.” He points to a section of beach beyond a seawall where wispy marsh grass stands thick in white sand, and oyster beds reach out from the sea like architectural ruins. A little more than a year ago there was no beach at all. Decades of dredging and miles of seawall had washed all the sand out to sea. But a five-year restorative effort by scientists at the University of Florida brought the beach back. By constructing a living shoreline—a protective barrier along the shore using natural elements—rather than building another concrete seawall, scientists have provided habitat for local species and created a carbon sink that absorbs carbon dioxide. “They’re following nature’s lead rather than trying to lead nature,” Davis says.

I could use the hope. These days, living along the Gulf of Mexico feels like a perennial exercise in adjusting to calamity. This summer a historic red tide outbreak washed up the bloated carcasses of dolphins, blue-green algae oozed across the state into the Gulf and the Atlantic, Hurricane Michael—fueled by warmer than usual Gulf water—sucker punched the Panhandle, and a U.N. panel released a doomsday climate report with dire warnings to coastal inhabitants. I am filled with dread.

Davis does not give into apocalyptic thinking, no matter how grim things seem. Perhaps because he’s a professor of environmental history and sustainability studies at the University of Florida, he doesn’t think in short time frames. Nor does he look at the Gulf as a passive backdrop to human drama. He sees the Gulf as a protagonist in the history of the United States. “I didn’t want the book to be dictated by human events. I wanted this to be the biography of a place,” he says.

The book took shape on April 20, 2010, when the BP Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded and gushed 210 million gallons of crude oil into the Gulf. “That 87-day nightmare robbed the Gulf of its true identity,” Davis says. “It was the headline every day. That’s how people came to think of the Gulf, as this oil sump. Five years before that it was Katrina. So, it’s either the Gulf as hurricane alley, an oil sump or a vacation beach.” Davis, the author of a number of Florida histories, could not abide this image of the Gulf, so he spent seven years researching and writing his own version of the sea he loves.

“Someone had to tell its story,” Davis says. “It’s as if the Gulf isn’t a part of U.S. history.”

Before Davis, no one had written a history of the Gulf. Though it is the 10th largest body of water in the world and the largest gulf, runs 3,000 miles along five U.S. states and Mexico, and has one of the world’s most dense and diverse fish populations, it’s never held our imagination like the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The Atlantic evokes postcards of lighthouses and visions of Moby Dick, while the Pacific is full of big waves and cliff-cut highways, but what represents the Gulf? Oil-soaked pelicans?

Davis takes us as far back as the Pleistocene, some 150 million years ago when North America broke away from Pangea. But the story of the Gulf’s impact on modern history begins 500 years ago with the indigenous people who once thrived along the Gulf until their fateful encounter with the Spanish conquistadors. Thinking of Juan Ponce de Leon, Panfilo de Narváez and Hernando de Soto as courageous explorers after reading Davis’s book is a travesty. Their violence and greed annihilated tens of thousands of indigenous people. (The reader may take solace in the Spaniards’ ignorance, however, since many starved amidst a sea abundant with protein-rich food.) Ultimately, disease defeated the native civilizations and the Gulf coast became the province of the Europeans and, eventually, that of their descendants, who believed in Manifest Destiny, the attitude that all resources in North America were for the taking as we raced across the continent claiming territory and riches.

Davis says we’re all connected to the Gulf, historically, ecologically and economically. A web of rivers from Minnesota to New York carries water and sediment and empties into the Gulf. A plowed field in Iowa makes its way down the Mississippi River and becomes a marsh beach in Louisiana. The windblown tips of the Appalachian Mountains become the white quartz sand of Siesta Key.

Commercial fishermen hauling in their seine net full of fish in Naples, Florida, circa 1949.

Davis’s own connection to the Gulf wasn’t clear to him until he left. He grew up on Fort Walton Beach in Pensacola and then later in Pinellas County. He remembers playing with his first seine net in the water with his sister when he was about 11. He expected to net a bunch of muck and sea grass, but instead saw a whole world of living things. “It just transformed my image of what grass was,” he says. “Even at that young age, I knew that the Gulf was very much this living and giving sea.”

As a young man, Davis joined the Navy in 1975. “I loved the ocean, so I signed up,” he says. “They promised I’d see the world, and I bit.” He returned to his old haunts in 1979, but Florida’s rapid growth left him with whiplash. “The landmarks I knew were gone. They’d been bulldozed, replaced,” he says, and he left again with no regrets, thinking that Florida lacked a sense of history and place. He received his bachelor’s in political science and master’s degree in history from the University of South Florida and his Ph.D. in history from Brandeis University. He taught at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where he was director of environmental studies. In 2003, he took a faculty position at the University of Florida. By this time, childhood memories of the Gulf began to call to him. He missed the smell of salt air.

Now, being landlocked is tough, he says. “So I like to look at the sky, and if I see clouds moving in from the west, I think, ‘Oh, I bet there’s Gulf water in those clouds.’”

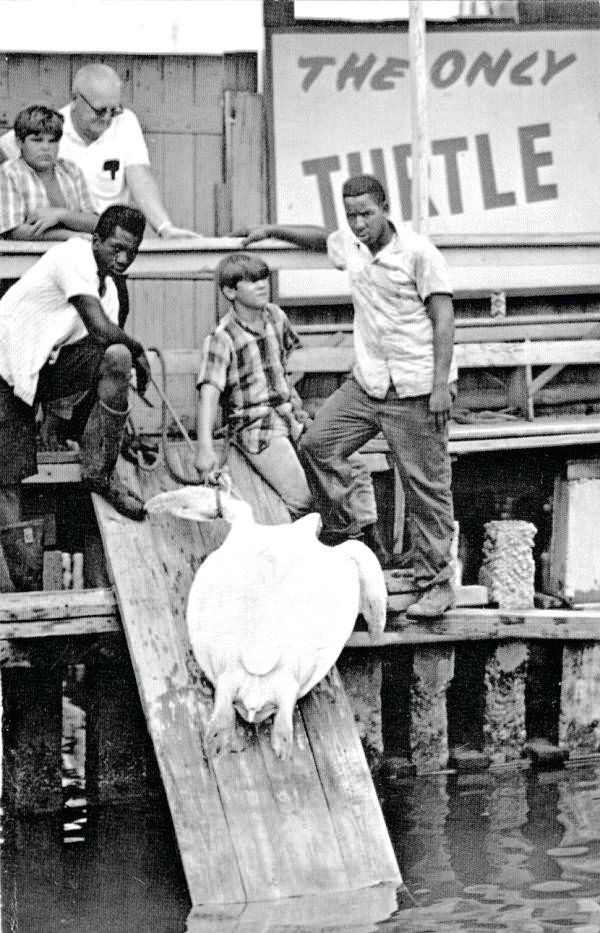

Green turtles, like this one being pulled in by fishermen, circa 1960, were considered delicacies.

Image: State Archives of Florida

Davis wants to show me physical evidence of this attachment. We hop in his Prius and head farther inland to Cedar Key’s Shell Mound archaeological site. The site is thick with palms and mosquitoes. The mound stands nearly 30 feet above sea level, built from empty clam and oyster shells from the indigenous people about a thousand years ago. We walk up its unsteady slope. Each step makes music, the old, sun-bleached shells chiming under our feet.

“The trees weren’t here,” Davis says when we reach the top. “They built these mounds on barren land. Back then, you could have seen the water from here.” This particular mound is likely a kitchen midden, in other words, a landfill. “A lot better kind of landfill than what we’re leaving behind,” Davis says.

Florida’s Gulf coast, including Sarasota’s, was covered with these shell mounds, created by the 350,000 natives who thrived around the Gulf’s estuaries, says Davis. Some were landfills like the one we stand on, but many were also ceremonial and burial mounds. Where did they go? In 1928, the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers chose to use nearly all of them for quarry to build the Tamiami Trail. Turns out we’ve been driving over native burial mounds every day for 90 years.

The Gulf’s riches, however, turned out to be its curse. Each chapter of Davis’s book is organized around an abundant natural characteristic of the Gulf, from birds to turtles to fish and pristine beaches, and the subsequent horror we inflicted on them. As Davis writes, “The blind pursuit of economic growth had transformed cradles of life into chambers of death.”

Tarpon, the “fish that tamed the coast” by luring tourists and bringing infrastructure to a place that was once uninhabitable to most Northerners, was so overfished by the turn of the 20th century that it appeared to be a contest, Davis writes, to see “who could make nature tender the most.”

The chapter on birds describes a time when they were so plentiful they blotted out the sun. Millions were killed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as feathers for women’s hats. On Pelican Island, near Galveston, Texas, a few “enterprising men,” as Davis describes them, killed and boiled every single pelican for oil. No market was ever found for their scheme. “Natural beauty encouraged borrowed beauty, while borrowed beauty decimated natural beauty,” Davis writes.

A chapter on sea turtles depicts beaches so covered with these ancient creatures that Davis writes that local people used to say, “you could walk across water like Jesus by stepping on their backs.”

Davis writes about Sarasota author John D. MacDonald, who loved the Gulf coast and lamented the construction of “instant Florida” while he watched dredges and heavy equipment yank out mangrove barriers. “And after they are dead, the damage they do goes on and on, visited on their descendants forever,” MacDonald wrote in his last novel. “Their great-grandchildren will live in a world that is drab, dirty, ugly and dangerous...sick and stinking.’”

After spending years digging into the awful history of modern man’s treatment of the Gulf, how can Davis stay optimistic? “I don’t know,” he says, leaning onto the wooden railing at the end of the dock. “Maybe I’m a fool? But what choice do we have? We can be totally cynical and be miserable. How does that benefit others? What kind of legacy would I be leaving my daughter or my students if I’m cynical? Do I want to pass along cynicism? Or do I want to pass along optimism with reality?”

Sport fishermen in the early 20th century flooded Florida to fish for tarpon.

Image: State Archives of Florida

Given a chance, the Gulf can heal, he says. Remember the living shoreline that scientists built? “Nature will reclaim itself,” Davis says. “When I was a kid in the ’60s and ’70s, there wasn’t a lot of birdlife. I never saw a wood stork or a roseate spoonbill or a white ibis. The bay and bayous were on the verge of death. We polluted them with waste water and raw sewage and industrial waste, so we wiped out the majority of the seagrass beds. But with the Clean Water Act of 1972, the Gulf came back to life.” Davis points to Sarasota’s efforts to stop dumping waste in the bay, starting 30 years ago. Sarasota’s seagrass beds came back, he says, and that brought back fish, and the fish bring back birds.

There is a long pause. I can hear the tide lapping up against the dock’s pillars in this place that fills The Gulf ’s last chapter—and Davis—with hope. Davis stands straight, puts his hands on his hips and looks out on the water of Cedar Key.

“Isn’t that beautiful?” he says, looking over the living shoreline that just a few years ago had no beach. “Just think of all the activities going on. In the grass, in the muck, on the water. We never see it, we don’t think about it. But to imagine at one time, not too long ago, people stood here and called this wasteland. That this is not worth a thing. There’s just so much life here.”

Click here to read an excerpt from The Gulf.

Lead photo of Jack E. Davis by Fred Lopez, shot on Cedar Key.