Economist, Black History Scholar and Professor James Stewart on Reparations and Economic Equality

This article is part of the series In Their Own Words, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

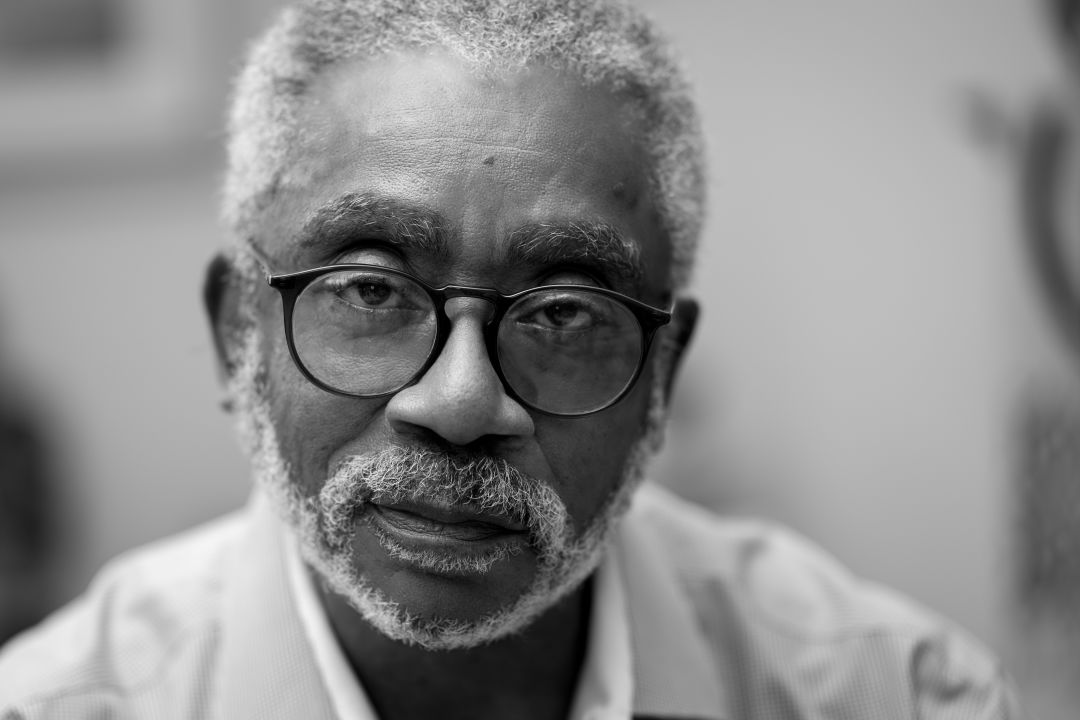

Dr. James Stewart

Image: Michael Kinsey

Since James Stewart was a young man, he’s had a heart for social justice and giving back to his community. After earning a doctorate in economics from the University of Notre Dame in 1976, he held many positions in higher education—including as a professor and administrator at Penn State University—with a focus on economics and Black history, subjects he often combined.

He also served as president of the National Economic Association, the National Council for Black Studies and conducted audits of Black/Africana Studies programs and departments at more than 20 colleges and universities across the country.

Now 73, Stewart is a professor emeritus at Penn State, has authored, co-authored, edited, or co-edited 11 books, and is president of the Manasota branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), the organization established by Carter G. Woodson, the founder of Black History Month.

Stewart, an avid collector of African artwork, moved to Sarasota in 2015 with his wife, Dr. Caryl Sheffield.

Tell us about your family roots in Cleveland.

“My family migrated to Cleveland from Mississippi in the late 1920s because my father was threatened with lynching. He was a sharecropper, which meant that he would purchase supplies and seeds from the landowner. One day he traveled to Jackson, where he found cheaper necessary utensils. When my father returned, he tried to negotiate the price of the tools with the landowner—who was a white blood relative—and it did not go well. He was told that he had 24 hours to get out of Mississippi or he would be lynched for asking. He made his way to Ohio, and four years later, after earning enough money, he sent for my mother, who had stayed in Mississippi.”

Even today, we do not have anti-lynching legislation. Why?

“The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has tried since the early 1900s to get anti-lynching legislation passed. One of the most recent efforts is the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, which was introduced in the House of Representatives by Rep. Bobby Rush in January 2019. It was sent to the Senate after it passed the House in February 2020. Although it is apparently supported by an overwhelming number of senators, its passage has been blocked by one person: Sen. Rand Paul.

“In my opinion, until this bill is passed and implementation procedures are put in place, the tradition of lynching as a means of social control is still on the table. Lynching is the most extreme example of socially accepted violence intended to keep Blacks in their place. Disproportionate police violence against Blacks is another component of this policy objective. Violent suppression is an integral element of the social fabric that continues to disenfranchise and intimidate people of color."

What was your childhood like?

“I grew up in the inner city in a working-class, all-Black neighborhood called Mt. Pleasant. I attended an all-Black elementary school, as districts were drawn to maintain segregation. Because I was good at academics and sports, my friends would say, ‘You’ll have a chance to get out of here. Don’t worry about bullies or fights, we’ve got your back,’ and they did.

“My experience growing up there motivated a lot of what I’ve done with my life—trying to improve the communities I live in and giving back to the less fortunate.”

What was your experience with the riots in the Black Cleveland neighborhood of Hough in the summer of 1966?

“I was 19 and enrolled at the Rose Hulman Institute of Technology in Indiana for my undergrad work, but I went home to Cleveland every summer. I observed the National Guard with its tanks and jeeps. You couldn’t go into Hough, because it was surrounded to maintain order, so my friends and I drove around the perimeter to see what was going on. The Hough Riots heightened my social justice consciousness.”

How so?

“When I returned to college, my roommate and I started a Black newsletter called the Black Student Voice. It was about 15 pages long, and we’d sell it for 25 cents. We only had five Black students at our school, so we would drive 10 minutes to the Indiana State University campus, which had a Black student enrollment of 300, and sell the newsletters there.

“One day, my roommate and I attended a protest at Indiana State where the students took over the administration building. A photo was taken with my roommate in the window, which prompted the FBI to come looking for the two of us. We were accused of running the Black student protests throughout the state of Indiana.

“In the wake of a speech by George Wallace on the Rose Hulman campus, we—the five Black of 1,100 students—demanded a Black history course be added to our college’s curriculum. The dean of students threatened to expel us. I was a math major and had a good relationship with the head of the department, a highly respected white professor. He stood up for us and we got the course in African-American history. I still have the textbook we used.”

How do you view the current unrest in comparison with your experience in the 1960s?

“Years of frustration over injustice build up. For Black Americans, opportunities are forestalled, from education to economics, and negative relationships exist with authorities, especially over policing. The years of disrespect fuel an inner rage, and eventually it boils over. Revolutions are launched from pent-up anger, and a single episode can provide the spark that leads to a major outburst. One event can seem like it’s coming out of nowhere, but it’s the culmination of subjugation that has been experienced over a long period of time.

“Because of this systemic oppression and institutional discrimination, we have found other means of taking care of our own psychological and emotional needs. Within the Black community, we have created Black organizations, fraternities, sororities, and more, which provide opportunities for Black achievements and acknowledgement, all away from discrimination.

“For example, I’m the president of the Sarasota Duplicate Bridge Club of the American Bridge Association, which is predominantly made up of Black members. It was created because the American Contract Bridge League historically did not accept Black members.”

You’re the co-author of the textbook Introduction to African-American Studies, Transdisciplinary Approaches and Implications, which includes an explanation of Blackness. Can you describe the evolution of language?

“Many different terms have been used to define the parameters of Black identity, such as ‘colored,’ ‘people of color,’ ‘Africans,’ and ‘Negro.’

“In the 1920s, scholars, authors and artists that birthed the New Negro Movement used the term Negro to express a new sense of defiance to Jim Crow segregation. It was a powerful political term. This group announced that they would no longer tolerate the indignities that were imposed upon the previous generation.

“During the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the word Negro came to be seen as an insult, and the activists of my generation settled on the term ‘Black’ to break with past conventions. This is the period where phrases like ‘Black power’ and ‘Black is beautiful’ emerged.

“The partial shift from Black to African American signals an effort to reconnect to our historical roots. Alex Haley’s movie Roots was an inspiration for many who identified with how Haley used the character Kunta Kinte to symbolize his own efforts to trace his ancestry. Now genetic research technologies allow some Black Americans, including me, to learn more about our African heritage.

“New and different terms are now surfacing, such as African Descendant of Slaves (ADOS). It has emerged because of the debate about reparations, and differentiates those who did and didn’t experience slavery in their heritage.”

You’ve published more than 75 articles on race and economics and served as editor of The Review of Black Political Economy. How can we achieve economic equality?

“Until the wealth gap is addressed, the disparities will persist. It is easier to reduce current income disparities than to build wealth. Wealth is the product of decades of saving, investing and, in many cases, appropriating the income of others. It is self-perpetuating. It’s easier to build wealth upon wealth rather than starting from scratch, which is the situation that most Blacks find themselves in—from the end of enslavement to the present.”

“Reparations is one remedy for this, but raises the issue of how to design a distribution plan. For example, reparations could be paid to individuals with no strings attached. Alternatively, they could be escrowed into a fund that would be used to fund initiatives such as business creation, scholarships, etc. Another idea for addressing the wealth gap is to institute a ‘baby bond’ program. Every child, irrespective of race or ethnicity, would receive a bond at birth. The amount would depend on each family’s resources—if the child is poor, they would get more than that of a wealthier baby. The value of the bonds would grow via interest and capital gains, and when the child reached adulthood, they would be able to use that money for an education, opening a business, or other opportunities. This would be a way to break the pattern of self-perpetuating wealth disparities.

“It’s also worth noting that a primary source of wealth is home ownership. This is one of the casualties for the Black and Latino communities due to Covid-19. Many are losing their homes and, therefore, the loss of a wealth-building opportunity.”

How would taxpayers be affected by reparations?

“One of the newest and most controversial economic theories is called New Monetary Theory. Its proponents argue that the size of the federal debt is not a constraint, because governments can print money freely as long as there are no inflationary pressures without any need to raise taxes.

“This is the idea that supported the passage of the recent $2 trillion Covid-19 relief package. The same approach could be applied to fund reparations payments. Instituting payments during the current crisis would not only address historical wrongs, but also provide relief for Blacks who have been disproportionately adversely impacted by the pandemic.”

In 1978, Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun wrote, “In order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of the race.” What did he mean?

“What Justice Blackmun meant is that disparities must be addressed in order to put people of color on the same footing as white citizens. Without race-specific interventions to overcome discrimination, racial identity only serves to put someone ahead, or behind, someone else.

“Lyndon Johnson, in a speech at Howard University in 1965, said, ‘You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, You are free to compete with all the others, and still justly believe that you have been completely fair. Thus it is not enough just to open the gates of opportunity. All our citizens must have the ability to walk through those gates.”’

“What works against that understanding is that somehow Americans thought that after Affirmative Action, or the election of a Black president, that everything is now equal for all, and that the historical disparities are no longer there. It’s not so, and it’s an unwillingness to recognize this reality.

“My approach to history discounts the idea that there is a linear path to better outcomes. I believe that it is possible to identify cyclical patterns in the way in which societies develop and atrophy. This is why we now see similarities between the way in which Black civil rights were eviscerated following Reconstruction after the Civil War and the current efforts to roll back the gains won through the civil rights and Black Power movements of the 1960s and 1970s.”

What inspires you about Black American culture?

“Resilience, and the ability to adapt to new challenges. I am inspired by the young activists taking up the mantle to combat discrimination and racism. I appreciate how they are using technology for mobilization, organization, and getting their message out through popular culture.”

What do you want your white friend/neighbor/colleague/community to be doing right now?

“I want them to educate themselves, and to educate within their network. You can ask me for insight; however, it is tiring for Black people to be the white community’s only resource. Plus, a white friend would be more effective in terms of communicating to other white people.”

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill