Venice Musician Dick Hyman Has Serious Hip Hop Cred

Rap producer Paul Huston, aka Prince Paul, found inspiration in the album Moog: The Electric Eclectics of Dick Hyman.

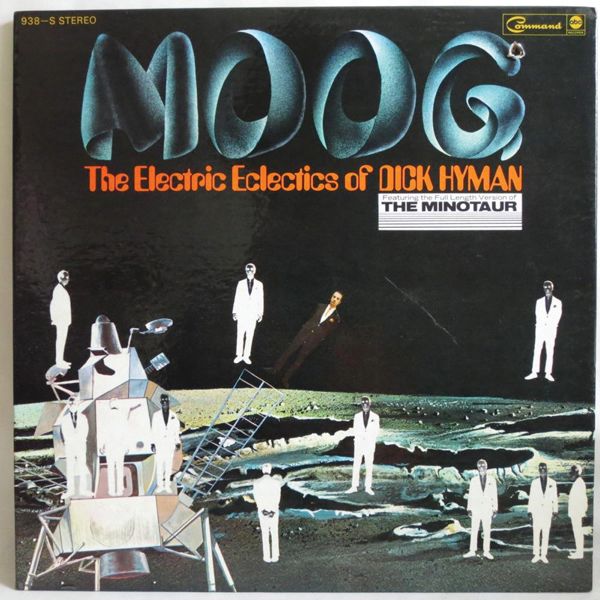

Paul Huston—better known as Prince Paul—discovered Moog: The Electric Eclectics of Dick Hyman sometime in the mid-'80s, in a New York City record store. Two things about the LP stood out: the cover, a moonscape populated by an Apollo spacecraft and cutouts of nattily dressed gentlemen, and the price. “I got it for a dollar,” says Huston with a laugh. “Money was hard to come by.”

Huston, then an aspiring hip hop DJ and producer, frequently scoured record shops for bargain albums, the rarer the better. It was a competition of sorts. DJs fought to find the funkiest, most out-there tracks to spin at block parties or layer into studio recordings.

Like its cover, Moog was spacey, a sequence of dreamy, funky soundscapes dominated by the sound of the analog synthesizer that gave the LP its name. Introduced to pop audiences in the mid-'60s, the Moog was still a novel instrument when Hyman, a pianist then best known for swing and Gershwin tunes, recorded the album, which was issued by Command Records in 1969.

Hyman would go on to gain fame as an arranger and composer, both of classical and jazz works, and as one of film director Woody Allen’s most frequent soundtrack collaborators. Today, now 89, he lives in Venice. He still travels the country performing and is a regular at local jazz gigs and festivals. “One thing I love about the Moog, it has an absolute glissando from a low note to a high note, which had some eerie effects,” he says.

Huston didn’t know how he might use Hyman’s Moog sound right away, but he liked it. “Those Moog records, they’re all over the place, loud and off, kind of not in time,” says Huston, now 49. “But there’s a real human feel to it. It’s not perfect, and that’s cool.” He filed Moog away in a vinyl collection that eventually grew to 50,000 records.

That collection, and the samples Huston mined from it, helped propel him to the forefront of hip hop. As the producer behind De La Soul’s first three LPs, 3 Feet High and Rising, De La Soul Is Dead and Buhlōōne Mindstate, Huston established himself as one of the most inventive music-makers in rap. Any list of the five most influential New York rap producers would certainly include Prince Paul. Huston created a dense tapestry of samples and beats, stitching together sounds nicked from Schoolhouse Rock!, Steely Dan, Chicago and anyone else that sounded right. Like Dick Hyman. “Patti Dooke,” a classic De La Soul cut from 1993, flips Hyman’s song “Improvisation in Fourths” behind rappers calling out “sucker MCs.”

Huston wouldn’t be the last rap producer to sample Hyman’s work, which has turned up in songs by Kendrick Lamar, J Dilla, Madlib, Busta Rhymes and even Kanye West, who used Hyman’s song “Kolumbo” in a tune he created for an Adidas ad. The Dust Brothers, legendary for their work on the Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique, took a short sequence of Hyman whistling and looped it to create a song for Beck’s multiplatinum 1996 album Odelay. On 1994’s immortal “Root Down,” the Beastie Boys gave Hyman a shout-out, even though the song didn’t sample him. “I’m electric like Dick Hyman,” raps Ad-Rock. “I guess you’d expect to catch the crew rhymin’.”

“I’m just amazed that people have found some relevance in them,” Hyman says of his Moog albums. “I’m very pleased when people do this, especially if they pay for it. Not everyone does.”

Because of that question of permission and payment, sampling has not always been greeted with enthusiasm by the original artists. In the crate-digging ’80s, there were few guidelines, but lawsuits and copyright claims eventually limited rap producers’ freedom to sample at will. Today rappers must get permission from the original artists and compensate them, but because of the huge decline in record sales, labels are now less willing to spend money to clear samples. That’s changed the sound of hip hop, which is now less based on samples than in its early years. Hyman’s work has often been used without his OK, but he says he’s not interested in taking legal action.

It’s a new reality, says Huston. “Either you pay and try to work out a deal, or you get creative and learn ways to manipulate technology to alter something or make it sound like your own, or you just out and out make it yourself,” he says. Since those early De La Soul albums, Huston has worked on a number of classic records, teaming with fellow hip hop pioneers like RZA and the Automator and releasing LPs under his own name.

He still has those 50,000 records, but he long ago gave up vinyl hunting. “Man, I got turned off from records once everyone started collecting,” he says. It used to be just DJs prowling dank basement record shops for potential beats. With the booming interest in vinyl, there’s no more mystery, Huston laments. Still, he loves the sound of those Dick Hyman tracks he first heard three decades ago, he says: “I think he’s dope.”