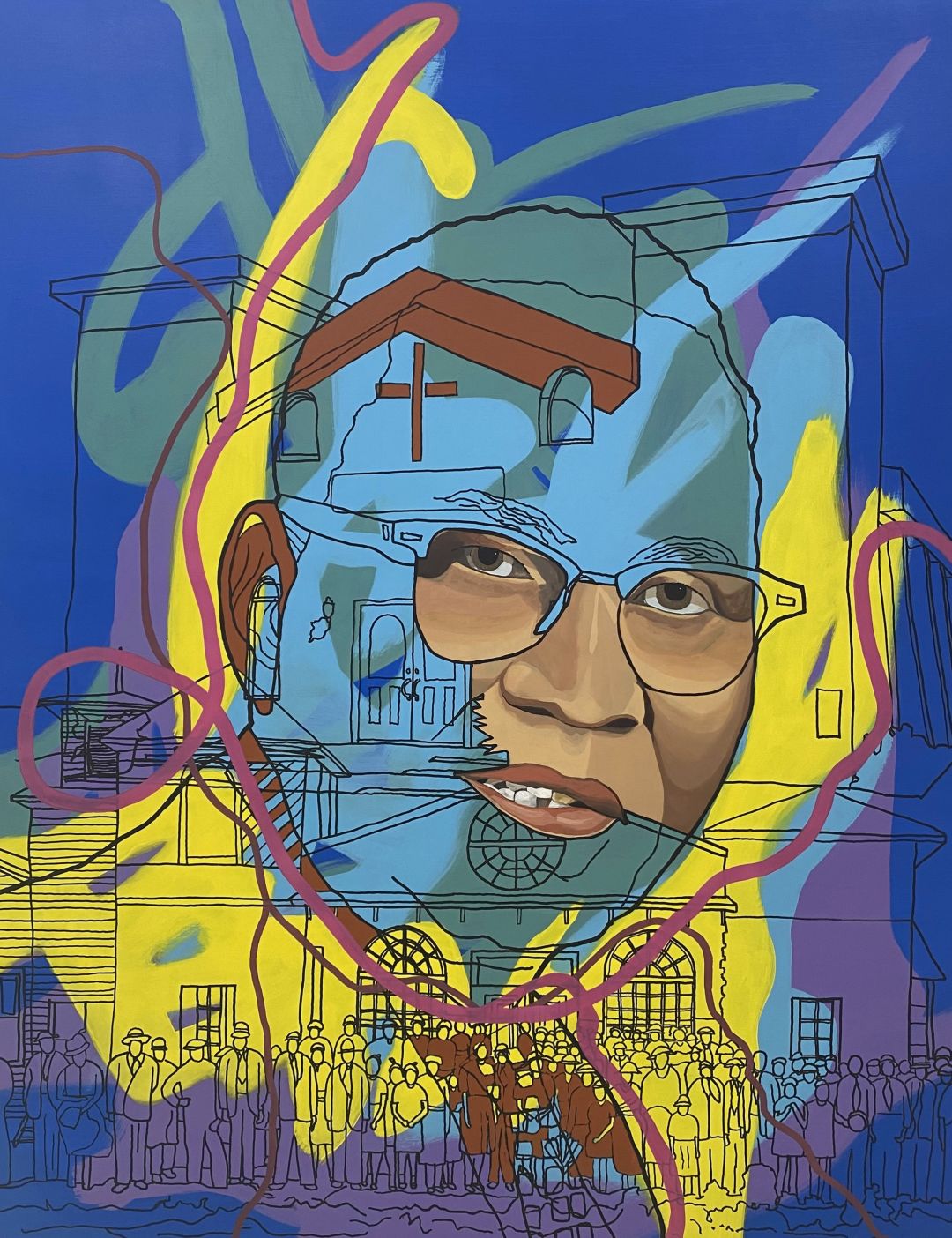

Architect Javi Suárez on His Puerto Rican Heritage, His Art and Making a Home in Sarasota

This article is part of the series Listening to Diverse Voices, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

Javi Suárez

Image: Michael Kinsey

With his father, Javier, architect Javi Suárez has long contributed to Sarasota’s physical profile with projects like the Sabal Palm building on Ringling Boulevard, the Capstan building in historic Towles Court, and the Sarasota Chamber of Commerce building on Fruitville Road. The elder Suárez was one of the first licensed Hispanic architects in the area when he moved here from Puerto Rico in the early 1980s with his family.

However, Javi, 49, can still easily conjure up the challenge of fitting in in Sarasota. He didn’t always feel welcome, despite the fact he wasn’t technically an outsider. As a territory of the United States, Puerto Rico's 3.2 million residents are U.S. citizens. However, while they're subject to the United States' federal laws, Puerto Ricans can't vote in presidential elections and lack representation in Congress.

Suárez has now spent roughly 40 years in the Sarasota area (minus a six-year stint in Los Angeles) and has made it his mission to tell the story of others who are cut from the same cloth he is. In addition to his architectural blueprints, he's also creative on canvas, and will show his latest body of artwork, Sarasota Icons, at the Art Ovation Hotel on Oct. 19. The series celebrates those who left their mark on Sarasota, from more obscure names to ubiquitous ones, from the past to today.

Image: Courtesy Photo

What was it like moving here when you were young?

"As a child, discrimination was much more in my face. I moved here in the fourth grade and knew six words of English. Then I had to go to middle school—it wasn't fun. My yearbook is signed, 'My favorite Spic.' Kids were calling me 'wetback' [a slur for people of Mexican descent] even though I'm not Mexican—but part of racism is that you're uneducated about people who don't look or sound like you."

Have things changed since then?

"Until now, I think people were less willing to be direct with their attitudes toward those who are different than them. You hear it in jokes people tell about people of color. Should I point out how racist that joke is? I don't know. I have, but it's draining. Is it worth the energy of explaining it? How much is really on us to speak up? We're the ones being attacked, but then you ask yourself if we also have to be the ones to teach."

How did it affect you?

"It's hard to stand up when you're one of the few who sound and look different and you're trying to make friends. You become a chameleon to fit into one group and flow to another. I left this community when I went to Los Angeles to find more diversity. Although we are a diverse community, we're isolated within it. Coming from the Caribbean, it's hard to explain my culture to many Americans because even though Puerto Ricans are born U.S. citizens, our makeup is more similar to Cuba and the Dominican Republic. You have every skin shade in your family tree, from my blue-eyed grandfather to my great-grandmother being very dark-skinned. Oftentimes, the perception is that Latin America is a large block of sameness, and it's anything but."

Do you think your children are having a different experience than yours growing up here?

"They've been bullied before, but they’re proud and identify strongly as Latino. I think our generation has opened some doors for them in terms of the perception of what you can be and accomplish. The demographics have also changed. There's a larger percentage of Latin Americans than when I was growing up here. But the rhetoric is probably just as bad, if not worse, than when I was a kid. Some people feel they don't have to have a filter anymore. And with social media, you can't escape certain attitudes. When I was growing up, you could leave that behind at school."

What do you wish more locals knew about Puerto Rico?

"Where it is on the map.

"Not assuming we're Mexican and that we're U.S. born.

"A little history. Puerto Rico was passed on from one colonizer to the next from Spain to the United States right before World War I, and 20,000 Puerto Ricans were drafted to serve. So there's a huge military service history there. My grandfather is buried at the National Cemetery here in Sarasota, and my cousin was in the Navy. There was a military base in Puerto Rico where the military did bombing practice and used biochemical agents, like Agent Orange, uranium and napalm. The base eventually shut down since it's a toxic site now, with higher levels of cancer and environmental damage left behind."

What changes are you seeing in the local Hispanic community?

"Organizations like UnidosNow are doing amazing things. I mentor through a program they have and talk to students interested in architecture. More and more Hispanics are looking to get into the field. There are more well-respected Hispanic professionals in the community, like Dr. Manuel Gordillo, the infectious disease expert at Sarasota Memorial Hospital, and that's great to see. I served on the board of the Ringling Museum for six years and was past president of the American Institute of Architecture's local chapter, too. There's more visibility, I think."

What inspired the Sarasota Icons series?

"I'm largely influenced by architecture and concepts surrounding cultural identity. I started thinking about the idea of icons and I want to tell the story of those in our own community to bring people together and tell their story from different points of view."

Who are some of the people you include in your work?

"There are the more well-known people like the Ringlings, but also lesser-known figures like Rev. John Henry Floyd, who was a prominent contractor in the Black community and built many churches and raised money to build the first retirement home for Sarasota’s Black citizens during segregation. There's also John Rivers, who fought for integration and became a leader in the Civil Rights Movement in Sarasota, and Dr. Ed James II, producer and host of ABC 7’s long-running Black Almanac. I also included Dr. Gordillo, who works hard to keep the public informed in fighting the Covid battle."

Why did you decide to stay in Sarasota?

"My family is here. And after nearly 40 years of giving back and creating, this is my home—as much as one can claim to be a Sarasotan. That's what I am."